Epigenetic regulation of neurogenesis

Epigenetics is the study of heritable changes in gene expression which do not result from modifications to the sequence of DNA. Neurogenesis is the mechanism for neuron proliferation and differentiation. It entails many different complex processes which are all time and order dependent.[1] Processes such as neuron proliferation, fate specification, differentiation, maturation, and functional integration of newborn cells into existing neuronal networks are all interconnected.[2] In the past decade many epigenetic regulatory mechanisms have been shown to play a large role in the timing and determination of neural stem cell lineages.[1]

Relevant Mechanisms & Definitions

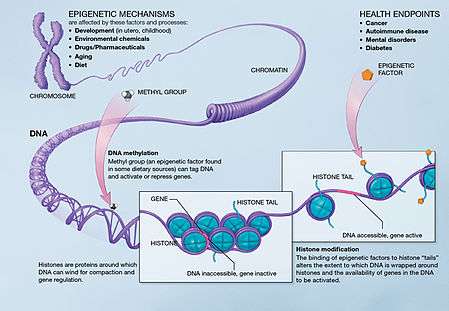

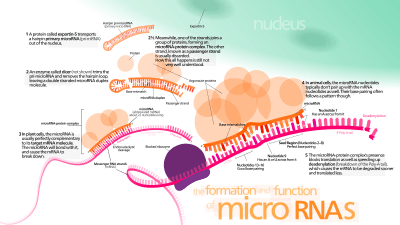

Three important methods of epigenetic regulation include histone modification, DNA methylation and demethylation, and MicroRNA (miRNA) expression. Histones keep the DNA of the eukaryotic cell tightly packaged through charge interactions between the positive charge on the histone tail and the negative charge of the DNA, as well as between histone tails of nearby nucleosomes.While there are many different types of Histone modifications, in neural epigenetics there are two primary mechanisms which have been explored: histone methylation and histone acetylation.[1][3] In the former, methyl groups are either added or removed to the histone altering its structure and exposing chromatin and leading to gene activation or deactivation. In the latter, histone acetylation causes the histone to hold the DNA more loosely, allowing for more gene activation. DNA Methylation, in which methyl groups are added to cytosine or adenosine redisdues on the DNA, is a more lasting method of gene inactivation than histone modification, though is still reversible in some cases.[1][3] MicroRNAs are a small form of non-coding RNA (ncRNA) which often act as "fine-tuning" mechanisms for gene expression by repressing or inducing messenger RNA (mRNA) in neural cells but can also act directly with transcription factors to guide neurogenesis.[1][3][4][5]

Epigenetic Regulation in the Brain

Embryonic Neurogenesis

Histone Modifications

Neural Stem Cells generate the cortex in a precise "inside out" manner with carefully controlled timing mechanisms. Early born neurons form deep layers in the cortex while newer born form the upper layers. This timing program is seen in vitro as well as in vivo.[1][3] Histone methylation has been shown to be one of the epigenetic regulatory mechanisms which alters the proportionate production of deep layer and upper layer neurons. Specifically, deletion of Ezh2 encoding histone methyltransferase led to a twofold reduction of BRN2-expressing and SATB2 expressing upper layer neurons without affecting the number of neurons in layer V and VI. Similarly, histone acetylation through histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor Valproic Acid, an epilepsy therapeutic, in mouse embryonic stem cell (ESC) derived neural proginetors not only induces neuronal differentiation, but also selectively enriched the upper layer neuronal population. As such, it has been proposed that HDAC inhibition promotes the progression of neuronal differentiation, leading to a fate-switch from deep-layer producing progenitors into upper-layer progenitors. However, the reasons behind this selective differentiation and timing control as a result of HDAC inhibition are not yet fully understood.[3]

DNA Methylation

DNA methylation's critical nature to corticogenesis has been shown through knockout experiments in mice. When DNMT3b and DNMT1 were ablated separately in mouse embryos they died due to impairment of neural tube development. DNMT3a silencing did not cause embryonic lethality, but did result in a severe detriment in postnatal neurogenesis.[1][3] This is largely due to the timing in which these epigenetic mechanisms are active. DNMT3b is expressed in early neural progenitor cells and decrease as neural development proceeds and DNMT3a is barely detectable up until embryonic day 10 (E.10). However, at E.10, DNMT3a expression increases significantly from E13.5 and well into adulthood. In the postnatal forebrain, DNMT3a is expressed in the subventricular zone (SVZ) and the hippocampal dentate gyrus, the primary locations for adult neurogenesis.[1][2] The loss of DNMT3a in post natal neural progenitor cells leads to the down-regulation of neuronic genes such as Dlx2, Neurog2, and Sp8; but upregulation of genes involved in astroglial and oligodendroglial differentiation, indicating a role in the cell-fate switch from neurogenesis to gliogenesis. DNA demethylation, as well as methylation, of certain genes allows for neurogenesis to proceed in a time dependent manner. One such gene is Hes5, hypermethylated in E7.5 Embryos but completely demethylated by E9.5, which is one of the target genes in the Notch Signaling pathway. GCM1 and GCM2 demethylate the Hes5 promoter, allowing it to respond to NOTCH signaling and initiating the generation of neural stem cells.[1] Another example is the Gfap gene which is required for astrocyte differentiation. The ability to differentiate into glial cells is repressed in neural stem cells with a neuronal cell fate. This repression is due largely to an irresponsiveness of neural stem cells towards astrocyte-inducing stimulations. The neural stem cells are non-responsive due to hypermethylated DNA in the promoter regions of astrocyte genes such as Gfap. The STAT3 binding site in the promoter region of Gfap is hypermethylated at E11.5 and barely so at E14.5, at which point it is able to receive astrocyte inducing stimulations and begin cytokine-inducible astrocyte differentiation.[3]

miRNAs

Studies done by De Pietri Tonelli and Kawase-Koga have shown conditional knockout of Dicer, an enzyme largely used for miRNA synthesis, in mouse neocortex resulted in reduced cortical size, increased neuronal apoptosis, and deficient corticol layering. Neuroepithelial cells and neuroprogenitor cells were not affected until E.14, at which point they also underwent apoptosis. This doesn't show which miRNAs were responsible for the varying factors affected, but it does show that there is a stage-specific requirement for miRNA expression in cortical development.[1][5][6][7] miR-124, the most abundant microRNA in the central nervous system, controls the lineage progression of subventricular zone neural progenitor cells into neuroblasts by suppressing protein production by targeting Sox9. Another major microRNA player is miR-9/9*. In embryonic neurogenesis miR-9 has been shown to regulate neuronal differentiation and self-renewal.[1][4][5] Ectopic expression of miR-9 in the developing mouse cortex led to premature neuronal differentiation and disrupted the migration of new neurons through targeting Foxg1.[1]

Contrary to the idea that microRNAs are only fine-tuning mechanisms, recent studies have shown that miR-9 and miR-124 can act together to guide fibroblasts into neural cells. Transcription factors and regulatory genes, such as Neurod1, Ascr1, and Myt1l, which were previously thought to be responsible for this phenomena did not transform human fibroblasts in the absence of miR-9 and miR-124, but in the presence of the microRNAs and the absence of the transcription factors human fibroblast transformation proceeded, albeit in a less efficient manner.[1][4][5]

Adult Neurogenesis

DNA Methylation

Neurogenesis continues after development well through adulthood.[2]Growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible, beta (GADD45b) is required for the demethylation of promoters of critical genes responsible for new-born neuron development such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and Basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF2).[8] As such, upregulation of GADD45b leads to increased demethylation, increased BDNF and FGF2, and ultimately more neural progenitor cells.[1][8]

Histone Modification

Histone deacetylation also plays a large role in the proliferation and self-renewal of post-natal neural stem cells. Neural-expressed HDACs interact with Tlx, an essential neural stem cell regulator, to suppress TLX target genes. This includes the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor P21 and the tumor suppressor gene Pten to promote neural stem cell proliferation. Inhibition of HDACS by the antiepileptic drug valproic acid induces neuronal differentiation as in embryonic neurogenesis, but also inhibits glial cell differentiation of adult neural stem cells. This is likely mediated through upregulation of neuronal specific genes such as the neurogeneic basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors NEUROD, NEUROGENENIN1, and Math1. Conditional loss of HDAC1 and HDAC2 in neural progenitor cells prevented them from differentiating into neurons and their loss in oligodendrytic progenitor cells disrupted oligodendrocyte formations, suggesting that histone deacetlyation plays important but varying roles in different stages of neuronal development.[1]

miRNAs

miR-9 targets the nuclear receptor TLX in adult neurogenesis to promote neural differentiation and inhibit neural stem cell proliferation. It also influences neuronal subtype specification and regulates axonal growth, branching, and targeting in the central nervous system through interactions with HES1, a neural stem cell homeostasis molecule.[1][5] miR-124 promotes cell cycle exit and neuronal differentiation in adult neurogensis. Mouse studies have shown that ectopic expression of miR-124 showed premature neural progenitor cell differentiation and exhaustion in the subventricular zone.[5]

In Memory

Histone acetylation has a dynamic role in controlling memory formation and synaptic plasticity. HDAC inhibitors exhibited positive effects on mice with cognitive defects such as Alzheimers disease and improved the cognition of wild type mice. HDAC2 has been shown to play a negative role in memory and learning. Sirt1, a histone acetylase, reduces memory formation ability by promoting the expression of miR-134, which targets the critical activity-dependent transcription factor (CREB) essential for learning and memory.[8]

The Growth Arrest and DNA Damage inducible 45 (Gadd45) gene family plays a large role in the hippocampus. Gadd45 facilitates hippocampal long-term potentiation and enhances persisting memory for motor performance, aversive conditioning, and spatial navigation.[9] Additionally, DNA methylation has been shown to be important for activity-dependent modulation of adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus, which is mediated by GADD45b. GADD45b seems to act as a sensor in mature neurons for environmental changes which it expresses through these methylation changes.[1] This was determined by examining the effects of applying an electric stimulus to the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) in normal and GADD45b knockout mice. In normal mice application of electrical stimulation to the DG increased neurogenesis by increasing BDNF. However, in GADD45b deficient mice the electrical stimulus had less of an effect. Further examination revealed that around 1.4% of CpG islands in DG neurons are actively methylated and demthylated upon electric shock. This shows that the post-mitotic methylation states of neurons are not static and given that electric shock equipment such as that used in the study has been shown to have therapeutic effects to human patients with depression and other psychiatric disorders, the possibility remains that epigenetic mechanisms may play an important role in the pathophysiology of neuropsychiatric disorders.[2][8] DNMT1 and DNMT3a are both required in conjunction for learning, memory, and synaptic plasticity.[8]

Epigenetic Misregulation & Neurological Disorders

Alterations on epigenomic machinery cause DNA methylation and Histone acetylation processes to go rogue, leading to alterations on the transcriptional level of genes involved in the pathogenesis of neural degenerative diseases such as Parkinsons Disease, Alzheimer's Disease, Schizophrenia, and Bipolar Disease.[1][10]

Alzheimer's Disease

MicroRNA expression is critical for neurogenesis. In patients with Alzheimer's disease miR-9 and miR-128 is upregulated, while miR-15a is downregulated.[4] Alzheimer's patients also show decreases in brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which has been shown to be repressed through DNA methylation.[8] Although what has been argued as the most evidence for epigenetic influence in Alzheimer's is the gene which controls the protein responsible for amyloid plaque formation, App. This gene has very high GC content in its promoter region, meaning that it is highly susceptible to DNA methylation. This promoter site has been shown to naturally reduce methylation with aging, exemplifying the parallels between aging and Alzheimer's already well known.[11][12] Heavy metals also seem to interfere with epigenetic mechanisms. Specifically in the case of APP, lead exposure earlier in life has been shown to cause a marked over-expression of the APP protein, leading to more amalyoid plaque later in life in the aging brain.[12]

DNA methylation's age relation has been further investigated in the promoter regions of several Alzheimer's related genes in the brains of postmortem late-onset Alzheimer's disease patients. The older patients seem to have more abnormal epigenetic machinery than the younger patients, despite the fact that both had died from Alzheimers. Though this in of itself is not conclusive evidence of anything, it has led to an age-related epigenetic drift theory where abnormalities in epigenetic machinery and exposure to certain environmental factors which occur earlier in life lead to aberrant DNA methylation patterns far later, contributing to sporadic Alzheimer's Disease predisposition.[12]

Histone modifications may also have an impact in Alzheimer's disease, but the differences between HDAC effects in rodent brains compared to human brains have researchers puzzled.[12] As the focus for neurodegenerative diseases begins to shift towards epigenetic pharmacology, it can be expected that the interactions of histone modifications with respect to neurogenesis will become more clear.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Hu, X.L.; Wang,Y.; Shen, Q. (2012). "Epigenetic control on cell fate choice in neural stem cells". Protein & Cell. 3 (4): 278–290. doi:10.1007/s13238-012-2916-6. PMID 22549586.

- 1 2 3 4 Faigle, Roland; Song, Hongjun (2013). "Signaling mechanisms regulating adult neural stem cells and neurogenesis". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1830 (2): 2435–2448. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.09.002. PMC 3541438

. PMID 22982587.

. PMID 22982587. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 MuhChyi, Chai; Juliandi, Berry; Matsuda, Taito; Nakashima, Kinichi (October 2013). "Epigenetic regulation of neural stem cell fate during corticogenesis". International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 31 (6): 424–433. doi:10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2013.02.006. PMID 23466416.

- 1 2 3 4 Ji, Fen; Lv, Xiaohui; Jiao, Jianwei (February 2013). "The Role of MicroRNAs in Neural Stem Cells and Neurogenesis". Journal of Genetics and Genomics. 40 (2): 61–66. doi:10.1016/j.jgg.2012.12.008. PMID 23439404.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sun, Alfred X; Crabtree, Gerald R; Yoo, Andrew S (April 2013). "MicroRNAs: regulators of neuronal fate". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 25 (2): 215–221. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2012.12.007. PMC 3836262

. PMID 23374323.

. PMID 23374323. - ↑ De Pietri Tonelli, D.; Pulvers, J. N.; Haffner, C.; Murchison, E. P.; Hannon, G. J.; Huttner, W. B. (23 October 2008). "miRNAs are essential for survival and differentiation of newborn neurons but not for expansion of neural progenitors during early neurogenesis in the mouse embryonic neocortex". Development. 135 (23): 3911–3921. doi:10.1242/dev.025080. PMC 2798592

. PMID 18997113.

. PMID 18997113. - ↑ Kawase-Koga, Y.; Low, R.; Otaegi, G.; Pollock, A.; Deng, H.; Eisenhaber, F.; Maurer-Stroh, S.; Sun, T. (26 January 2010). "RNAase-III enzyme Dicer maintains signaling pathways for differentiation and survival in mouse cortical neural stem cells". Journal of Cell Science. 123 (4): 586–594. doi:10.1242/jcs.059659. PMC 2818196

. PMID 20103535.

. PMID 20103535. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lv, Jingwen; Yongjuan Xin; Wenhao Zhou; Zilong Qiu (2013). "The Epigenetic Switches for Neural Development and Psychiatric Disorders". Journal of Genetics and Genomics. 40 (7): 339–346. doi:10.1016/j.jgg.2013.04.007. PMID 23876774.

- ↑ Sultan, Faraz; Jing Wang; Jennifer Tront; Dan Liebermann; J. David Sweatt (2012). "Genetic Deletion of gadd45b, a Regulator of Active DNA Demethylation, Enhances Long-Term Memory and Synaptic Plasticity". The Journal of Neuroscience. 32 (48): 17059–17066. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1747-12.2012. PMC 3518911

. PMID 23197699.

. PMID 23197699. - ↑ Dempster, E. L.; Pidsley, R.; Schalkwyk, L. C.; Owens, S.; Georgiades, A.; Kane, F.; Kalidindi, S.; Picchioni, M.; Kravariti, E.; Toulopoulou, T.; Murray, R. M.; Mill, J. (9 September 2011). "Disease-associated epigenetic changes in monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder". Human Molecular Genetics. 20 (24): 4786–4796. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddr416. PMC 3221539

. PMID 21908516.

. PMID 21908516. - ↑ Balazs, R; Vernon, J; Hardy, J (July 2011). "Epigenetic mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease: progress but much to do". Neurobiology of Aging. 32 (7): 1181–7. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.02.024. PMID 21669333.

- 1 2 3 4 Daniilidou, M; Koutroumani, M; Tsolaki, M (2011). "Epigenetic mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease". Current medicinal chemistry. 18 (12): 1751–6. doi:10.2174/092986711795496872. PMID 21466476.

External links

- Database of known microRNAs: http://www.miRbase.org

- Article on Histone methylation visualization through fluorescent imaging: http://www.the-scientist.com/?articles.view/articleNo/37155/title/Precision-Epigenetics/