European Development Fund

| European Union |

This article is part of a series on the |

Policies and issues

|

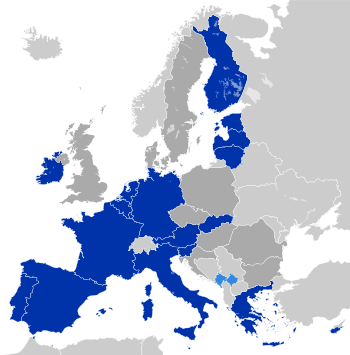

The European Development Fund (EDF) is the main instrument for European Union (EU) aid for development cooperation in Africa, the Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP Group) countries and the Overseas Countries and Territories (OCT). Funding is provided by voluntary donations by EU member states.[1] The EDF is subject to its own financial rules and procedures, and is managed by the European Commission (EC) and the European Investment Bank.[2]

Articles 131 and 136 of the 1957 Treaty of Rome provided for its creation with a view to granting technical and financial assistance to African countries that were still colonised at that time and with which certain countries had historical links.

Usually lasting 6 years, each EDF lays out EU assistance to both individual countries and regions as a whole. The EU is on its 10th EDF from 2008-2013 with a budget of €22.7 billion.[1] This represents about 30% of EU spending on development cooperation aid, with the remainder coming directly from the EU budget.[1]

The budget of the 10th EDF can be broken down as follows:[3]

- €21 966 million to the ACP countries (97% of the total),

- €17 766 million to the national and regional indicative programmes (81% of the ACP total),

- €2 700 million to intra-ACP and intra-regional cooperation (12% of the ACP total),

- €1 500 million to Investment Facilities (7% of the ACP total).

- €286 million to the OCTs (1% of the total),

- €430 million to the Commission as support expenditure for programming and implementation of the EDF (2% of the total).

Negotiations for the 11th EDF would cover the period 2014-2020. This one-year extension compared to the 10th EDF allowed the end of the 11th EDF to coincide with the expiration of the Cotonou Partnership Agreement in 2020 and the EU budget period.[2] The EDF has to date been funded outside the EU budget by the EU Member States on the basis of financial payments related to specific contribution shares, or “keys”. The Member State contributions keys are subject to negotiation. The EDF is the only EU policy instrument that is financed through a specific key that is different from the EU budget key, and which reflects the comparative interests of individual Member States.[2]

There was a debate on whether to 'budgetise' the EDF.[1] However, in the Communication ‘A budget for Europe 2020’, the European Commission underlined that it was not appropriate at present time to propose that the EDF be integrated into the EU budget.[2] The perceived advantages include:[1]

- contributions would be based on GNI and this may increase the voluntary contributions

- the harmonisation of EU budget and EDF administration might decrease administration costs and increase effectiveness of the aid

- 20% of aid to the ACP countries already originates from the EU budget

- an all-ACP geographic strategy is no longer relevant as programmes are more localised to regions or country-level

- there would be increase democratic control and parliamentary scrutiny

The perceived disadvantages are that:[1]

- 90% of EDF resources reach low-income countries as opposed to less than 40% of aid from the EU budget development instruments

- a loss of aid predictability and aid quality as the EU budget is annual, unlike the 6-year budget of the EDF

In 2005, the EU and its Member States agreed to achieve a collective level of ODA of 0.7% of GNI by 2015 and an interim target of 0.56% by 2010, with differentiated intermediate targets for those EU Member States which had recently joined the Union. On the 23rd of May 2011, EU ministers responsible for development cooperation gathered to take stock of progress made and concluded that additional efforts would be needed to close an estimated gap of €50 billion to reach the self-imposed collective EU target of 0.7% by 2015.[2]

By 2015, the EU had not reached 0.7% of GNI, though the commitment to this target was recently reaffirmed. The commitment held no deadline. Concord, the European confederation for relief and development, described the pledge as “vague and non-binding” and said 2020 should be the new deadline.[4]

The EU's 'Agenda for Change'

The European Commission’s development strategy – Agenda for Change – puts ‘inclusive and sustainable growth for human development’ at its centre. Adopted in 2011, it adopted 2 reforms designed to make its development policy both more strategic and more targeted. The Agenda for Change made new policies and rules for budget support. The three main elements of this Agenda were:

(1) Targeting and concentrating aid[5]

(2) Budget support (or 'State Building Contracts[6] in fragile states)

(3) Other reforms for effectiveness - joint programming, common results framework, innovative financing (such as blending loans and grants[7]), and Policy Coherence for Development

Programming the 11th European Development Fund

The EU is currently implementing its 11th European Development Fund for the period 2014-2020, with an aid budget of €30.5 billion for many of the ACP countries and Overseas Countries and Territories (OCTs), covering both national and regional programmes. Effectively programming the European Development Fund (EDF) is a major political, policy and bureaucratic challenge, involving multiple stakeholders, namely the European Commission (EC), the European External Action Service (EEAS), 28 EU member states, the European Parliament, 74 governments from the Africa, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) group of states and domestic accountability actors.

Understanding the magnitude of the 11th EDF programming challenge is critical for three reasons:

(1) The 11th EDF unfolds in a radically changed global context for development cooperation, as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were agreed in September 2015.

(2) The 11th EDF is the last before the Cotonou Partnership Agreement (CPA) between the EU and the countries of the ACP expires in 2020.[8]

(3) Programming and implementing the 11th EDF is a critical test of EU institutions that deal with external action, and it tests the ability of EU development policy to achieve high-impact aid, at a time when showing 'value for money' is a high political priority at a time when many European governments follow a policy of fiscal austerity.

Independent research by the European Centre for Development Policy Management (ECDPM), a think tank based in Maastricht (The Netherlands), shows that the EU has ensured the effective translation into practice of two key policy commitments of the 'Agenda for Change' - namely a more focused strategy for less developed countries (LDCs) and low-income countries (LICs), and the concentration of EU aid on a limited number of sectors and policy priorities. Their research found that the high degree of compliance was achieved "through top-level support and tight control from headquarters".[9]

While the principles of the 'Agenda for Change' appear to have been followed, ECDPM showed that in many countries initial programming proposals based on in-country consultations, managed by EU Delegations, were then superseded by the choices of EU headquarters in Brussels. Although the 11th EDF is closely aligned with national development plans, there is evidence that this top-down approach to programming has led to a significant erosion of key aid and development effectiveness principles, in particular country ownership.[9]

Critics

The European Development Fund has been criticized because they can not prove what was purchased with the tsunami relief money.[10][11]

See also

- Development Cooperation Instrument

- ACP-EU Development Cooperation

- ACP-EU Joint Parliamentary Assembly

- EuropeAid Co-Operation Office

- The Courier – a former magazine of Africa-Caribbean-Pacific and European Union cooperation and relations

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mikaela Gavas 2010. Financing European development cooperation: the Financial Perspectives 2014-2020. London: Overseas Development Institute

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kilnes, U., N. Keijzer, J. van Seters and A. Sherriff More or less? A financial analysis of the proposed 11th European Development Fund (ECDPM Briefing Note 29). Maastricht: European Centre for Development Policy Management (ECDPM)

- ↑ "European Development Fund (EDF)". European Commission. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Clár Ní Chonghaile. "EU draws fire for failing to set date for 0.7% aid target". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ↑ "Changes in the EU's "Agenda for Change"?". ECDPM. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ↑ "Analysis of the EU's State Building Contracts - ECDPM". ECDPM. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ↑ "Blending Loans Grants Development Effective Mix EU? - ECDPM". ECDPM. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ↑ "Dossier: The Future of ACP-EU Relations Post-2020 - ECDPM". ECDPM. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- 1 2 "Programming the 11th EDF - an independent analysis". ECDPM. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 31, 2015. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

External links

- Europa: Summaries of EU legislation: European Development Fund

- What is 10th EDF programming? EC aid programming for ACP countries

- EC Aid to Africa African Voices in Europe