Aldol reaction

| Aldol reaction | |

|---|---|

| Reaction type | Coupling reaction |

| Identifiers | |

| Organic Chemistry Portal | aldol-addition |

| RSC ontology ID | RXNO:0000016 |

The aldol reaction is a means of forming carbon–carbon bonds in organic chemistry.[1][2][3] Discovered independently by the Russian chemist Alexander Borodin in 1869[4] and by the French chemist Charles-Adolphe Wurtz in 1872,[5][6][7] the reaction combines two carbonyl compounds (the original experiments used aldehydes) to form a new β-hydroxy carbonyl compound. These products are known as aldols, from the aldehyde + alcohol, a structural motif seen in many of the products. Aldol structural units are found in many important molecules, whether naturally occurring or synthetic.[8][9][10] For example, the aldol reaction has been used in the large-scale production of the commodity chemical pentaerythritol[11] and the synthesis of the heart disease drug Lipitor (atorvastatin, calcium salt).[12][13]

The aldol reaction unites two relatively simple molecules into a more complex one. Increased complexity arises because up to two new stereogenic centers (on the α- and β-carbon of the aldol adduct, marked with asterisks in the scheme below) are formed. Modern methodology is capable of not only allowing aldol reactions to proceed in high yield but also controlling both the relative and absolute configuration of these stereocenters.[14] This ability to selectively synthesize a particular stereoisomer is significant because different stereoisomers can have very different chemical and biological properties.

For example, stereogenic aldol units are especially common in polyketides, a class of molecules found in biological organisms. In nature, polyketides are synthesized by enzymes that effect iterative Claisen condensations. The 1,3-dicarbonyl products of these reactions can then be variously derivatized to produce a wide variety of interesting structures. Often, such derivitization involves the reduction of one of the carbonyl groups, producing the aldol subunit. Some of these structures have potent biological properties: the immunosuppressant FK506, the anti-tumor agent discodermolide, or the antifungal agent amphotericin B, for example. Although the synthesis of many such compounds was once considered nearly impossible, aldol methodology has allowed their efficient synthesis in many cases.[15]

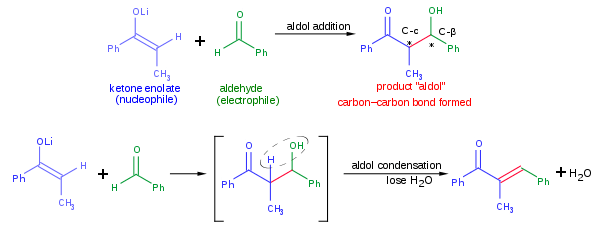

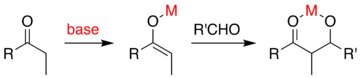

A typical modern aldol addition reaction, shown above, might involve the nucleophilic addition of a ketone enolate to an aldehyde. Once formed, the aldol product can sometimes lose a molecule of water to form an α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compound. This is called aldol condensation. A variety of nucleophiles may be employed in the aldol reaction, including the enols, enolates, and enol ethers of ketones, aldehydes, and many other carbonyl compounds. The electrophilic partner is usually an aldehyde or ketone (many variations, such as the Mannich reaction, exist). When the nucleophile and electrophile are different, the reaction is called a crossed aldol reaction; on the converse, when the nucleophile and electrophile are the same, the reaction is called an aldol dimerization.

The flask on the right is a solution of lithium diisopropylamide (LDA) in tetrahydrofuran (THF). The flask on the left is a solution of the lithium enolate of tert-butyl propionate (formed by addition of LDA to tert-butyl propionate). An aldehyde can then be added to the enolate flask to initiate an aldol addition reaction.

Both flasks are submerged in a dry ice/acetone cooling bath (−78 °C) the temperature of which is being monitored by a thermocouple (the wire on the left).

Mechanisms

The aldol reaction may proceed via two fundamentally different mechanisms. Carbonyl compounds, such as aldehydes and ketones, can be converted to enols or enol ethers. These species, being nucleophilic at the α-carbon, can attack especially reactive protonated carbonyls such as protonated aldehydes. This is the 'enol mechanism'. Carbonyl compounds, being carbon acids, can also be deprotonated to form enolates, which are much more nucleophilic than enols or enol ethers and can attack electrophiles directly. The usual electrophile is an aldehyde, since ketones are much less reactive. This is the 'enolate mechanism'.

If the conditions are particularly harsh (e.g.: NaOMe/MeOH/reflux), condensation may occur, but this can usually be avoided with mild reagents and low temperatures (e.g., LDA (a strong base), THF, −78 °C). Although the aldol addition usually proceeds to near completion under irreversible conditions, the isolated aldol adducts are sensitive to base-induced retro-aldol cleavage to return starting materials. In contrast, retro-aldol condensations are rare, but possible.[16]

Enol mechanism

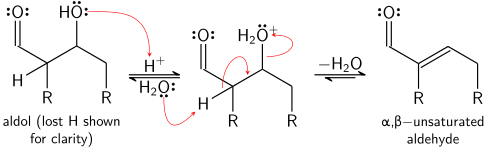

When an acid catalyst is used, the initial step in the reaction mechanism involves acid-catalyzed tautomerization of the carbonyl compound to the enol. The acid also serves to activate the carbonyl group of another molecule by protonation, rendering it highly electrophilic. The enol is nucleophilic at the α-carbon, allowing it to attack the protonated carbonyl compound, leading to the aldol after deprotonation. This usually dehydrates to give the unsaturated carbonyl compound. The scheme shows a typical acid-catalyzed self-condensation of an aldehyde.

Acid-catalyzed aldol mechanism

Acid-catalyzed dehydration

Enolate mechanism

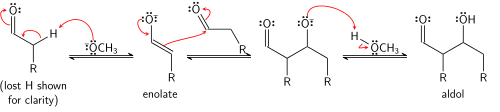

If the catalyst is a moderate base such as hydroxide ion or an alkoxide, the aldol reaction occurs via nucleophilic attack by the resonance-stabilized enolate on the carbonyl group of another molecule. The product is the alkoxide salt of the aldol product. The aldol itself is then formed, and it may then undergo dehydration to give the unsaturated carbonyl compound. The scheme shows a simple mechanism for the base-catalyzed aldol reaction of an aldehyde with itself.

Base-catalyzed aldol reaction (shown using −OCH3 as base)

Base-catalyzed dehydration (frequently written incorrectly as a single step, see E1cB elimination reaction)

Although only a catalytic amount of base is required in some cases, the more usual procedure is to use a stoichiometric amount of a strong base such as LDA or NaHMDS. In this case, enolate formation is irreversible, and the aldol product is not formed until the metal alkoxide of the aldol product is protonated in a separate workup step.

Zimmerman–Traxler model

More refined forms of the mechanism are known. In 1957, Zimmerman and Traxler proposed that some aldol reactions have "six-membered transition states having a chair conformation."[17] This is now known as the Zimmerman–Traxler model. E-enolates give rise to anti products, whereas Z-enolates give rise to syn products. The factors that control selectivity are the preference for placing substituents equatorially in six-membered transition states and the avoidance of syn-pentane interactions, respectively.[18] E and Z refer to the cis-trans stereochemical relationship between the enolate oxygen bearing the positive counterion and the highest priority group on the alpha carbon. In reality, only some metals such as lithium and boron reliably follow the Zimmerman–Traxler model. Thus, in some cases, the stereochemical outcome of the reaction may be unpredictable.

Crossed-aldol reactant control

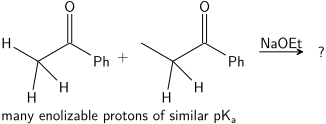

The problem of "control" in the aldol addition is best demonstrated by an example. Consider the outcome of this hypothetical reaction:

In this reaction, two unsymmetrical ketones are being condensed using sodium ethoxide. The basicity of sodium ethoxide is such that it cannot fully deprotonate either of the ketones, but can produce small amounts of the sodium enolate of both ketones. This means that, in addition to being potential aldol electrophiles, both ketones may also act as nucleophiles via their sodium enolate. Two electrophiles and two nucleophiles, then, have potential to result in four possible products:

Thus, if one wishes to obtain only one of the cross-products, one must control which carbonyl becomes the nucleophilic enol/enolate and which remains in its electrophilic carbonyl form.

Acidity

The simplest control is if only one of the reactants has acidic protons, and only this molecule forms the enolate. For example, the addition of diethyl malonate into benzaldehyde would produce only one product. Only the malonate has α hydrogens, so it is the nucleophilic partner, whereas the non-enolizeable benzaldehyde can only be the electrophile:

The malonate is particularly easy to deprotonate because the α position is flanked by more than one carbonyl. Double-activation makes the enolate more stable, so not as strong a base is required to form it. An extension of this effect can allow control over which of the two carbonyl reactants becomes the enolate even if both do have α hydrogens. If one partner is considerably more acidic than the other, the most acidic proton is abstracted by the base and an enolate is formed at that carbonyl while the carbonyl that is less acidic is not affected by the base. This type of control works only if the difference in acidity is large enough and no excess of base is used for the reaction. A typical substrate for this situation is when the deprotonatable position is activated by more than one carbonyl-like group. Common examples include a CH2 group flanked by two carbonyls or nitriles (see for example the Knoevenagel condensation and the first steps of the Malonic ester synthesis).

Order of addition

One common solution is to form the enolate of one partner first, and then add the other partner under kinetic control.[19] Kinetic control means that the forward aldol addition reaction must be significantly faster than the reverse retro-aldol reaction. For this approach to succeed, two other conditions must also be satisfied; it must be possible to quantitatively form the enolate of one partner, and the forward aldol reaction must be significantly faster than the transfer of the enolate from one partner to another. Common kinetic control conditions involve the formation of the enolate of a ketone with LDA at −78 °C, followed by the slow addition of an aldehyde.

Enolates

Formation

The enolate may be formed by using a strong base ("hard conditions") or using a Lewis acid and a weak base ("soft conditions"):

In this diagram, B: represents the base which takes the proton. The dibutylboron triflate actually becomes attached to the oxygen only during the reaction. The second product on the right (formed from the N,N-diisopropylethylamine) should be i-Pr2EtNH+ OTf −.

For deprotonation to occur, the stereoelectronic requirement is that the alpha-C-H sigma bond must be able to overlap with the pi* orbital of the carbonyl:

Geometry

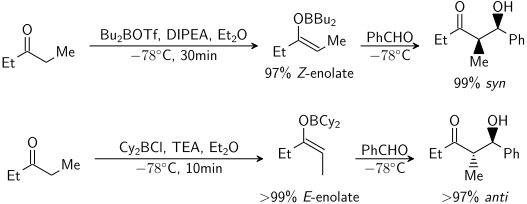

Extensive studies have been performed on the formation of enolates under many different conditions. It is now possible to generate, in most cases, the desired enolate geometry:[20]

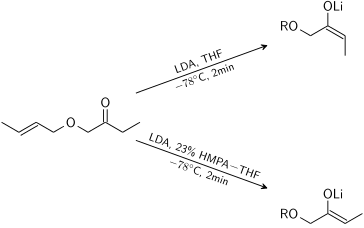

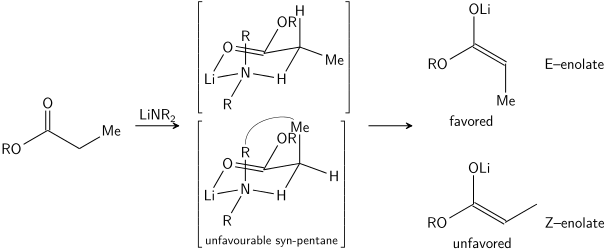

For ketones, most enolization conditions give Z enolates. For esters, most enolization conditions give E enolates. The addition of HMPA is known to reverse the stereoselectivity of deprotonation.

The stereoselective formation of enolates has been rationalized with the Ireland model,[21][22][23][24] although its validity is somewhat questionable. In most cases, it is not known which, if any, intermediates are monomeric or oligomeric in nature; nonetheless, the Ireland model remains a useful tool for understanding enolates.

In the Ireland model, the deprotonation is assumed to proceed by a six-membered or cyclic[25] monomeric transition state. The larger of the two substituents on the electrophile (in the case above, methyl is larger than proton) adopts an equatorial disposition in the favored transition state, leading to a preference for E enolates. The model clearly fails in many cases; for example, if the solvent mixture is changed from THF to 23% HMPA-THF (as seen above), the enolate geometry is reversed, which is inconsistent with this model and its cyclic transition state.

Regiochemistry

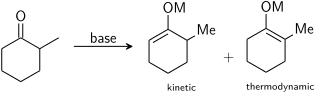

If an unsymmetrical ketone is subjected to base, it has the potential to form two regioisomeric enolates (ignoring enolate geometry). For example:

The trisubstituted enolate is considered the kinetic enolate, while the tetrasubstituted enolate is considered the thermodynamic enolate. The alpha hydrogen deprotonated to form the kinetic enolate is less hindered, and therefore deprotonated more quickly. In general, tetrasubstituted olefins are more stable than trisubstituted olefins due to hyperconjugative stabilization. The ratio of enolate regioisomers is heavily influenced by the choice of base. For the above example, kinetic control may be established with LDA at −78 °C, giving 99:1 selectivity of kinetic: thermodynamic enolate, while thermodynamic control may be established with triphenylmethyllithium at room temperature, giving 10:90 selectivity.

In general, kinetic enolates are favored by cold temperatures, conditions that give relatively ionic metal–oxygen bonding, and rapid deprotonation using a slight excess of a strong, sterically hindered base. The large base only deprotonates the more accessible hydrogen, and the low temperatures and excess base help avoid equilibration to the more stable alternate enolate after initial enolate formation. Thermodynamic enolates are favored by longer equilibration times at higher temperatures, conditions that give relatively covalent metal–oxygen bonding, and use of a slight sub-stoichiometric amount of strong base. By using insufficient base to deprotonate all of the carbonyl molecules, the enolates and carbonyls can exchange protons with each other and equilibrate to their more stable isomer. Using various metals and solvents can provide control over the amount of ionic character in the metal–oxygen bond.

Stereoselectivity

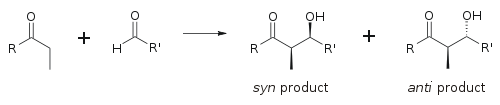

The aldol reaction is particularly useful because two new stereogenic centers are generated in one reaction. Extensive research has been performed to understand the reaction mechanism and improve the selectivity observed under many different conditions. The syn/anti convention is commonly used to denote the relative stereochemistry at the α- and β-carbon.

The convention applies when propionate (or higher order) nucleophiles are added to aldehydes. The R group of the ketone and the R' group of the aldehyde are aligned in a "zig zag" pattern in the plane of the paper (or screen), and the disposition of the formed stereocenters is deemed syn or anti, depending if they are on the same or opposite sides of the main chain.

Older papers use the erythro/threo nomenclature familiar from carbohydrate chemistry.

Enolate geometry

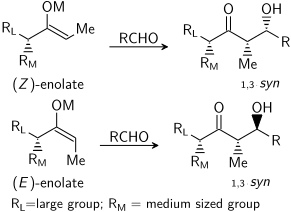

There is no significant difference between the level of stereoinduction observed with E and Z enolates. Each alkene geometry leads primarily to one specific relative stereochemistry in the product, E giving anti and Z giving syn:[20]

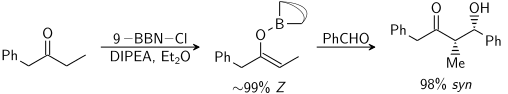

Metal ion

The enolate metal cation may play a large role in determining the level of stereoselectivity in the aldol reaction. Boron is often used[26][27] because its bond lengths are significantly shorter than that of other metals such as lithium, aluminium, or magnesium.

For example, boron–carbon and boron–oxygen bonds are 1.4–1.5 Å and 1.5–1.6 Å in length, respectively, whereas typical metal-carbon and metal-oxygen bonds are 1.9–2.2 Å and 2.0–2.2 Å in length, respectively. The use of boron rather than a metal "tightens" the transition state and gives greater stereoselectivity in the reaction.[28] Thus the above reaction gives a syn:anti ratio of 80:20 using a lithium enolate compared to 97:3 using a bibutylboron enolate.

Alpha stereocenter on the enolate

The aldol reaction may exhibit "substrate-based stereocontrol", in which existing chirality on either reactant influences the stereochemical outcome of the reaction. This has been extensively studied, and in many cases, one can predict the sense of asymmetric induction, if not the absolute level of diastereoselectivity. If the enolate contains a stereocenter in the alpha position, excellent stereocontrol may be realized.

In the case of an E enolate, the dominant control element is allylic 1,3-strain whereas in the case of a Z enolate, the dominant control element is the avoidance of 1,3-diaxial interactions. The general model is presented below:

For clarity, the stereocenter on the enolate has been epimerized; in reality, the opposite diastereoface of the aldehyde would have been attacked. In both cases, the 1,3-syn diastereomer is favored. There are many examples of this type of stereocontrol:[29]

Alpha stereocenter on the electrophile

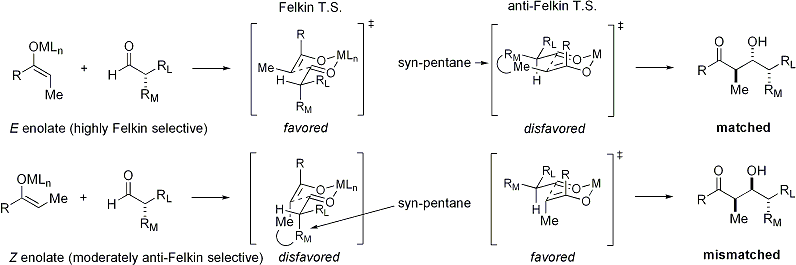

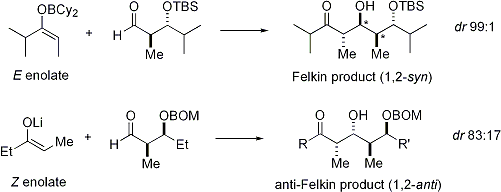

When enolates attacks aldehydes with an alpha stereocenter, excellent stereocontrol is also possible. The general observation is that E enolates exhibit Felkin diastereoface selection, while Z enolates exhibit anti-Felkin selectivity. The general model[30][31] is presented below:

Since Z enolates must react through a transition state that contains either a destabilizing syn-pentane interaction or an anti-Felkin rotamer, Z-enolates exhibit lower levels of diastereoselectivity in this case. Some examples are presented below:[32][33]

Unified model of stereoinduction

If both the enolate and the aldehyde both contain pre-existing chirality, then the outcome of the "double stereodifferentiating" aldol reaction may be predicted using a merged stereochemical model that takes into account the enolate facial bias, enolate geometry, and aldehyde facial bias.[34] Several examples of the application of this model are given below:[33]

Evans' oxazolidinone chemistry

Modern organic syntheses now require the synthesis of compounds in enantiopure form. Since the aldol addition reaction creates two new stereocenters, up to four stereoisomers may result.

Many methods which control both relative stereochemistry (i.e., syn or anti, as discussed above) and absolute stereochemistry (i.e., R or S) have been developed.

A widely used method is the Evans' acyl oxazolidinone method.[35][36] Developed in the late 1970s and 1980s by David A. Evans and coworkers, the method works by temporarily creating a chiral enolate by appending a chiral auxiliary. The pre-existing chirality from the auxiliary is then transferred to the aldol adduct by performing a diastereoselective aldol reaction. Upon subsequent removal of the auxiliary, the desired aldol stereoisomer is revealed.

In the case of the Evans' method, the chiral auxiliary appended is an oxazolidinone, and the resulting carbonyl compound is an imide. A number of oxazolidinones are now readily available in both enantiomeric forms. These may cost roughly $10–$20 US dollars per gram, rendering them relatively expensive. However, enantiopure oxazolidinones are derived in 2 synthetic steps from comparatively inexpensive amino acids, which means that large-scale syntheses can be made more economical by in-house preparation. This usually involves borohydride mediated reduction of the acid moiety, followed by condensation/cyclisation of the resulting amino alcohol with a simple carbonate ester such as diethylcarbonate.

The acylation of an oxazolidinone is a convenient procedure, and is informally referred to as "loading done". Z-enolates, leading to syn-aldol adducts, can be reliably formed using boron-mediated soft enolization:[37]

Often, a single diastereomer may be obtained by one crystallization of the aldol adduct. However, anti-aldol adducts cannot be obtained reliably with the Evans method. Despite the cost and the limitation to give only syn adducts, the method's superior reliability, ease of use, and versatility render it the method of choice in many situations. Many methods are available for the cleavage of the auxiliary:[38]

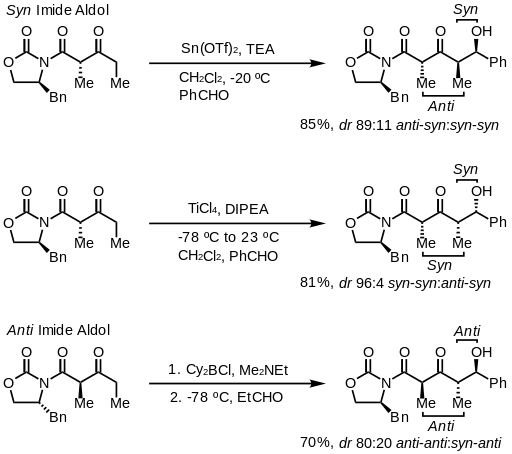

Upon construction of the imide, both syn- and anti-selective aldol addition reactions may be performed, allowing the assemblage of three of the four possible stereoarrays: syn selective:[39] and anti selective:[40]

In the syn-selective reactions, both enolization methods give the Z enolate, as expected; however, the stereochemical outcome of the reaction is controlled by the methyl stereocenter, rather than the chirality of the oxazolidinone. The methods described allow the stereoselective assembly of polyketides, a class of natural products that often feature the aldol retron.

Modern variations and methods

Recent methodology now allows a much wider variety of aldol reactions to be conducted, often with a catalytic amount of chiral ligand. When reactions employ small amounts of enantiomerically pure ligands to induce the formation of enantiomerically pure products, the reactions are typically termed "catalytic, asymmetric"; for example, many different catalytic, asymmetric aldol reactions are now available.

Acetate aldol reactions

A key limitation to the chiral auxiliary approach described previously is the failure of N-acetyl imides to react selectively. An early approach was to use a temporary thioether group:[38][41]

Mukaiyama aldol reaction

The Mukaiyama aldol reaction[42] is the nucleophilic addition of silyl enol ethers to aldehydes catalyzed by a Lewis acid such as boron trifluoride or titanium tetrachloride.[43][44] The Mukaiyama aldol reaction does not follow the Zimmerman-Traxler model. Carreira has described particularly useful asymmetric methodology with silyl ketene acetals, noteworthy for its high levels of enantioselectivity and wide substrate scope.[45]

The method works on unbranched aliphatic aldehydes, which are often poor electrophiles for catalytic, asymmetric processes. This may be due to poor electronic and steric differentiation between their enantiofaces.

The analogous vinylogous Mukaiyama aldol process can also be rendered catalytic and asymmetric. The example shown below works efficiently for aromatic (but not aliphatic) aldehydes and the mechanism is believed to involve a chiral, metal-bound dienolate.[46][47]

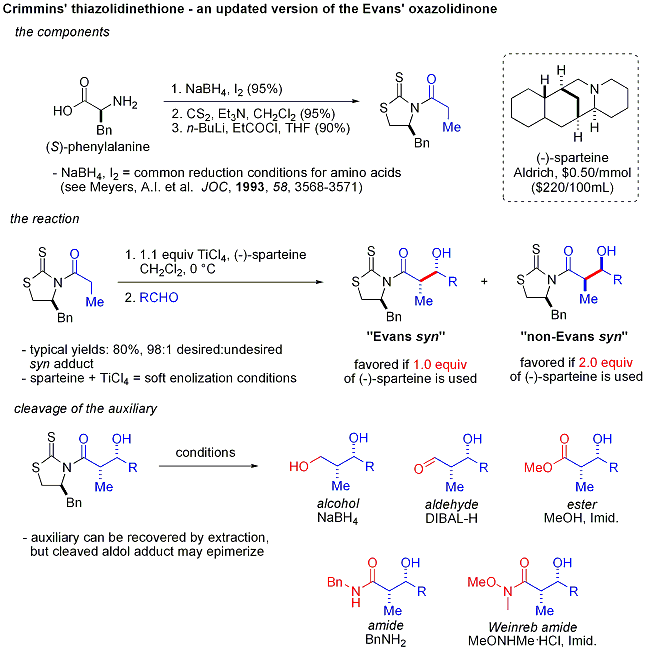

Crimmins thiazolidinethione aldol

A more recent version of the Evans' auxiliary is the Crimmins thiazolidinethione.[48][49] The yields, diastereoselectivities, and enantioselectivities of the reaction are, in general, high, although not as high as in comparable Evans cases. Unlike the Evans auxiliary, however, the thiazoldinethione can perform acetate aldol reactions (ref: Crimmins, Org. Lett. 2007, 9(1), 149–152.) and can produce the "Evans syn" or "non-Evans syn" adducts by simply varying the amount of (−)-sparteine. The reaction is believed to proceed via six-membered, titanium-bound transition states, analogous to the proposed transition states for the Evans auxiliary. NOTE: the structure of sparteine shown below is missing a N atom.

Organocatalysis

A more recent development is the use of chiral secondary amine catalysts. These secondary amines form transient enamines when exposed to ketones, which may react enantioselectively[50] with suitable aldehyde electrophiles. The amine reacts with the carbonyl to form an enamine, the enamine acts as an enol-like nucleophile, and then the amine is released from the product all—the amine itself is a catalyst. This enamine catalysis method is a type of organocatalysis, since the catalyst is entirely based on a small organic molecule. In a seminal example, proline efficiently catalyzed the cyclization of a triketone:

This reaction is known as the Hajos-Parrish reaction[51][52] (also known as the Hajos-Parrish-Eder-Sauer-Wiechert reaction, referring to a contemporaneous report from Schering of the reaction under harsher conditions).[53] Under the Hajos-Parrish conditions only a catalytic amount of proline is necessary (3 mol%). There is no danger of an achiral background reaction because the transient enamine intermediates are much more nucleophilic than their parent ketone enols. This strategy offers a simple way of generating enantioselectivity in reactions without using transition metals, which have the possible disadvantages of being toxic or expensive.

It is interesting to note that proline-catalyzed aldol reactions do not show any non-linear effects (the enantioselectivity of the products is directly proportional to the enantiopurity of the catalyst). Combined with isotopic labelling evidence and computational studies, the proposed reaction mechanism for proline-catalyzed aldol reactions is as follows:[54]

This strategy allows the otherwise challenging cross-aldol reaction between two aldehydes. In general, cross-aldol reactions between aldehydes are typically challenging because they can polymerize easily or react unselectively to give a statistical mixture of products. The first example is shown below:[55]

In contrast to the preference for syn adducts typically observed in enolate-based aldol additions, these organocatalyzed aldol additions are anti-selective. In many cases, the organocatalytic conditions are mild enough to avoid polymerization. However, selectivity requires the slow syringe-pump controlled addition of the desired electrophilic partner because both reacting partners typically have enolizable protons. If one aldehyde has no enolizable protons or alpha- or beta-branching, additional control can be achieved.

An elegant demonstration of the power of asymmetric organocatalytic aldol reactions was disclosed by MacMillan and coworkers in 2004 in their synthesis of differentially protected carbohydrates. While traditional synthetic methods accomplish the synthesis of hexoses using variations of iterative protection-deprotection strategies, requiring 8–14 steps, organocatalysis can access many of the same substrates using an efficient two-step protocol involving the proline-catalyzed dimerization of alpha-oxyaldehydes followed by tandem Mukaiyama aldol cyclization.

The aldol dimerization of alpha-oxyaldehydes requires that the aldol adduct, itself an aldehyde, be inert to further aldol reactions.[56] Earlier studies revealed that aldehydes bearing alpha-alkyloxy or alpha-silyloxy substituents were suitable for this reaction, while aldehydes bearing Electron-withdrawing groups such as acetoxy were unreactive. The protected erythrose product could then be converted to four possible sugars via Mukaiyama aldol addition followed by lactol formation. This requires appropriate diastereocontrol in the Mukaiyama aldol addition and the product silyloxycarbenium ion to preferentially cyclize, rather than undergo further aldol reaction. In the end, glucose, mannose, and allose were synthesized:

"Direct" aldol additions

In the usual aldol addition, a carbonyl compound is deprotonated to form the enolate. The enolate is added to an aldehyde or ketone, which forms an alkoxide, which is then protonated on workup. A superior method, in principle, would avoid the requirement for a multistep sequence in favor of a "direct" reaction that could be done in a single process step. One idea is to generate the enolate using a metal catalyst that is released after the aldol addition mechanism. The general problem is that the addition generates an alkoxide, which is much more basic than the starting materials. This product binds tightly to the metal, preventing it from reacting with additional carbonyl reactants.

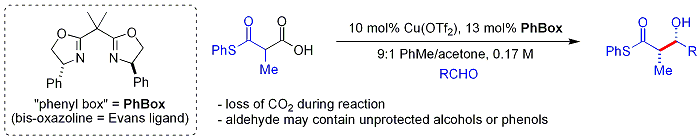

One approach, demonstrated by Evans, is to silylate the aldol adduct.[57][58] A silicon reagent such as TMSCl is added in the reaction, which replaces the metal on the alkoxide, allowing turnover of the metal catalyst. Minimizing the number of reaction steps and amount of reactive chemicals used leads to a cost-effective and industrially useful reaction.

A more recent biomimetic approach by Shair uses beta-thioketoacids as the nucleophile.[59] The ketoacid moiety is decarboxylated in situ. The process is similar to the way malonyl-CoA is used by Polyketide synthases. The chiral ligand is case is a bisoxazoline. Interestingly, aromatic and branched aliphatic aldehydes are typically poor substrates.

Biological aldol reactions

Examples of aldol reactions in biochemistry include the splitting of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate into dihydroxyacetone and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate in the fourth stage of glycolysis, which is an example of a reverse ("retro") aldol reaction catalyzed by the enzyme aldolase A (also known as fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase).

In the glyoxylate cycle of plants and some prokaryotes, isocitrate lyase produces glyoxylate and succinate from isocitrate. Following deprotonation of the OH group, isocitrate lyase cleaves isocitrate into the four-carbon succinate and the two-carbon glyoxylate via an aldol cleavage reaction. This cleavage is very similar mechanistically to the aldolase A reaction of glycolysis.

See also

References

- ↑ Wade, L. G. (2005). Organic Chemistry (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. pp. 1056–66. ISBN 0-13-236731-9.

- ↑ Smith, M. B.; March, J. (2001). Advanced Organic Chemistry (5th ed.). New York: Wiley Interscience. pp. 1218–23. ISBN 0-471-58589-0.

- ↑ Mahrwald, R. (2004). Modern Aldol Reactions, Volumes 1 and 2. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. pp. 1218–23. ISBN 3-527-30714-1.

- ↑ See:

- Borodin reported on the condensation of pentanal (Valerianaldehyd) with heptanal (Oenanthaldehyd) in: von Richter, V. (1869) "V. von Richter, aus St. Petersburg am 17. October 1869" (V. von Richter [reporting] from St. Petersburg on 17. October 1869), Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft, 2 : 552-553.

- English version of Richter's report: (Staff) (December 10, 1869) "Chemical notices from foreign sources: Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin, no. 16, 1869: Valerian aldehyde and Oenanth aldehyde – M. Borodin," The Chemical News and Journal of Industrial Science, 20 : 286.

- Garner, Susan Amy (2007) "Hydrogen-mediated carbon-carbon bond formations: Applied to reductive aldol and Mannich reactions," Ph.D. dissertation, University of Texas (Austin), pp. 4 and 51.

- Borodin, A. (1873) "Ueber einen neuen Abkömmling des Valerals" (On a new derivative of valerian aldehyde [i.e., pentanal]), Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft, 6 : 982–985.

- ↑ Wurtz, C. A. (1872). "Sur un aldéhyde-alcool". Bulletin de la Société chimique de Paris. 2nd series. 17: 436–442.

- ↑ Wurtz, C. A. (1872). "Ueber einen Aldehyd-Alkohol". Journal für Praktische Chemie. 2nd series. 5 (1): 457–464. doi:10.1002/prac.18720050148.

- ↑ Wurtz, C. A. (1872). "Sur un aldéhyde-alcool". Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences (in French). 74: 1361.

- ↑ Heathcock, C. H. (1991). "The Aldol Reaction: Acid and General Base Catalysis". In Trost, B. M.; Fleming, I. Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. 2. Elsevier Science. pp. 133–179. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-052349-1.00027-5. ISBN 978-0-08-052349-1.

- ↑ Mukaiyama T. (1982). "The Directed Aldol Reaction". Org. React. 28: 203–331. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or028.03. ISBN 0471264180.

- ↑ Paterson, I. (1988). "New Asymmetric Aldol Methodology Using Boron Enolates". Chem. Ind. 12: 390–394.

- ↑ Mestres R. (2004). "A green look at the aldol reaction". Green Chemistry. 6 (12): 583–603. doi:10.1039/b409143b.

- ↑ M. Braun; R. Devant (1984). "(R) and (S)-2-acetoxy-1,1,2-triphenylethanol – effective synthetic equivalents of a chiral acetate enolate". Tetrahedron Letters. 25 (44): 5031–4. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)91110-4.

- ↑ Jie Jack Li; et al. (2004). Contemporary Drug Synthesis. Wiley-Interscience. pp. 118–. ISBN 0-471-21480-9.

- ↑ Wulff W. D.; Andersson B. A (1994). "Stereoselective aldol addition reactions of Fischer carbene complexes via electronic tuning of the metal center for enolate reactivity". Inorganica Chimica Acta. 220 (1-2): 215–231. doi:10.1016/0020-1693(94)03874-0.

- ↑ Schetter, B.; Mahrwald, R. (2006). "Modern Aldol Methods for the Total Synthesis of Polyketides". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45 (45): 7506–7525. doi:10.1002/anie.200602780. PMID 17103481.

- ↑ Guthrie, J.P.; Cooper, K.J.; Cossar, J.; Dawson, B.A.; Taylor, K.F. (1984). "The retroaldol reaction of cinnamaldehyde". Can. J. Chem. 62 (8): 1441–1445. doi:10.1139/v84-243.

- ↑ Zimmerman, H. E.; Traxler, M. D. (1957). "The Stereochemistry of the Ivanov and Reformatsky Reactions. I". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 79 (8): 1920–1923. doi:10.1021/ja01565a041.

- ↑ Heathcock, C. H.; Buse, C. T.; Kleschnick, W. A.; Pirrung, M. C.; Sohn, J. E.; Lampe, J. (1980). "Acyclic stereoselection. 7. Stereoselective synthesis of 2-alkyl-3-hydroxy carbonyl compounds by aldol condensation". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 45 (6): 1066–1081. doi:10.1021/jo01294a030.

- ↑ Bal, B.; Buse, C. T.; Smith, K.; Heathcock, C. H., (2SR,3RS)-2,4-Dimethyl-3-Hydroxypentanoic Acid, Org. Syn., Coll. Vol. 7, p.185 (1990); Vol. 63, p.89 (1985).

- 1 2 Brown, H. C.; Dhar, R. K.; Bakshi, R. K.; Pandiarajan, P. K.; Singaram, B. (1989). "Major effect of the leaving group in dialkylboron chlorides and triflates in controlling the stereospecific conversion of ketones into either E- or Z-enol borinates". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 111 (9): 3441–3442. doi:10.1021/ja00191a058.

- ↑ Ireland, R. E.; Willard, A. K. (1975). "The stereoselective generation of ester enolates". Tetrahedron Letters. 16 (46): 3975–3978. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)91213-9.

- ↑ Narula, A. S. (1981). "An analysis of the diastereomeric transition state interactions for the kinetic deprotonation of acyclic carbonyl derivatives with lithium diisopropylamide". Tetrahedron Letters. 22 (41): 4119–4122. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)82081-5.

- ↑ Ireland, RE; Wipf, P; Armstrong, JD (1991). "Stereochemical control in the ester enolate Claisen rearrangement. 1. Stereoselectivity in silyl ketene acetal formation". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 56 (2): 650–657. doi:10.1021/jo00002a030.

- ↑ Xie, L; Isenberger, KM; Held, G; Dahl, LM (October 1997). "Highly Stereoselective Kinetic Enolate Formation: Steric vs Electronic Effects". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 62 (21): 7516–7519. doi:10.1021/jo971260a. PMID 11671880.

- ↑ Directed Aldol Synthesis – Formation of E-enolate and Z-enolate

- ↑ Cowden, C. J.; Paterson, I. Org. React. 1997, 51, 1.

- ↑ Cowden, C. J.; Paterson, I. (2004). Asymmetric Aldol Reactions Using Boron Enolates. Organic Reactions. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or051.01.

- ↑ Evans, D. A.; Nelson J. V.; Vogel E.; Taber T. R. (1981). "Stereoselective aldol condensations via boron enolates". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 103 (11): 3099–3111. doi:10.1021/ja00401a031.

- ↑ Evans, D. A.; Rieger D. L.; Bilodeau M. T.; Urpi F. (1991). "Stereoselective aldol reactions of chlorotitanium enolates. An efficient method for the assemblage of polypropionate-related synthons". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 113 (3): 1047–1049. doi:10.1021/ja00003a051.

- ↑ Evans D. A. et al. Top. Stereochem. 1982, 13, 1–115. (Review)

- ↑ Roush W. R. (1991). "Concerning the diastereofacial selectivity of the aldol reactions of .alpha.-methyl chiral aldehydes and lithium and boron propionate enolates". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 56 (13): 4151–4157. doi:10.1021/jo00013a015.

- ↑ Masamune S.; Ellingboe J. W.; Choy W. (1982). "Aldol strategy: coordination of the lithium cation with an alkoxy substituent". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 104 (20): 1047–1049. doi:10.1021/ja00384a062.

- 1 2 Evans, D. A.; Dart M. J.; Duffy J. L.; Rieger D. L. (1995). "Double Stereodifferentiating Aldol Reactions. The Documentation of "Partially Matched" Aldol Bond Constructions in the Assemblage of Polypropionate Systems". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 117 (35): 9073–9074. doi:10.1021/ja00140a027.

- ↑ Masamune S.; Choy W.; Petersen J. S.; Sita L. R. (1985). "Double Asymmetric Synthesis and a New Strategy for Stereochemical Control in Organic Synthesis". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 24: 1–30. doi:10.1002/anie.198500013.

- ↑ Evans D. A. Aldrichimica Acta 1982, 15, 23. (Review)

- ↑ Gage J. R.; Evans D. A., Diastereoselective Aldol Condensation Using A Chiral Oxazolidinone Auxiliary: (2S*,3S*)-3-Hydroxy-3-Phenyl-2-Methylpropanoic Acid, Organic Syntheses, Coll. Vol. 8, p.339 (1993); Vol. 68, p.83 (1990).

- ↑ Evans, D. A.; Bartroli J.; Shih T. L. (1981). "Enantioselective aldol condensations. 2. Erythro-selective chiral aldol condensations via boron enolates". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 103 (8): 2127–2129. doi:10.1021/ja00398a058.

- 1 2 Evans, D. A.; Bender S. L.; Morris J. (1988). "The total synthesis of the polyether antibiotic X-206". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 110 (8): 2506–2526. doi:10.1021/ja00216a026.

- ↑ Evans, D. A.; Clark J.S.; Metternich R.; Sheppard G.S. (1990). "Diastereoselective aldol reactions using .beta.-keto imide derived enolates. A versatile approach to the assemblage of polypropionate systems". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 112 (2): 866–868. doi:10.1021/ja00158a056.

- ↑ Evans, D. A.; Ng, H.P.; Clark, J.S.; Rieger, D.L. (1992). "Diastereoselective anti aldol reactions of chiral ethyl ketones. Enantioselective processes for the synthesis of polypropionate natural products". Tetrahedron. 48 (11): 2127–2142. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)88879-7.

- ↑ In this reaction the nucleophile is a boron enolate derived from reaction with dibutylboron triflate (nBu2BOTf), the base is N,N-Diisopropylethylamine. The thioether is removed in step 2 by Raney Nickel / hydrogen reduction

- ↑ S. B. Jennifer Kan; Kenneth K.-H. Ng; Ian Paterson (2013). "The Impact of the Mukaiyama Aldol Reaction in Total Synthesis". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 52 (35): 9097–9108. doi:10.1002/anie.201303914.

- ↑ Teruaki Mukaiyama; Kazuo Banno; Koichi Narasaka (1974). "Reactions of silyl enol ethers with carbonyl compounds activated by titanium tetrachloride". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 96 (24): 7503–7509. doi:10.1021/ja00831a019.

- ↑ 3-Hydroxy-3-Methyl-1-Phenyl-1-Butanone by Crossed Aldol Reaction Teruaki Mukaiyama and Koichi Narasaka Organic Syntheses, Coll. Vol. 8, p.323 (1993); Vol. 65, p.6 (1987)

- ↑ Carreira E.M.; Singer R.A.; Lee W.S. (1994). "Catalytic, enantioselective aldol additions with methyl and ethyl acetate O-silyl enolates — a chira; tridentate chelate as a ligand for titanium(IV)". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 116 (19): 8837–8. doi:10.1021/ja00098a065.

- ↑ Kruger J.; Carreira E.M. (1998). "Apparent catalytic generation of chiral metal enolates: Enantioselective dienolate additions to aldehydes mediated by Tol-BINAP center Cu(II) fluoride complexes". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 120 (4): 837–8. doi:10.1021/ja973331t.

- ↑ Pagenkopf B.L.; Kruger J.; Stojanovic A.; Carreira E.M. (1998). "Mechanistic insights into Cu-catalyzed asymmetric aldol reactions: Chemical and spectroscopic evidence for a metalloenolate intermediate". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 37 (22): 3124–6. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981204)37:22<3124::AID-ANIE3124>3.0.CO;2-1.

- ↑ Crimmins M. T.; King B. W.; Tabet A. E. (1997). "Asymmetric Aldol Additions with Titanium Enolates of Acyloxazolidinethiones: Dependence of Selectivity on Amine Base and Lewis Acid Stoichiometry". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 119 (33): 7883–7884. doi:10.1021/ja9716721.

- ↑ Crimmins M. T.; Chaudhary K. (2000). "Titanium enolates of thiazolidinethione chiral auxiliaries: Versatile tools for asymmetric aldol additions". Organic Letters. 2 (6): 775–777. doi:10.1021/ol9913901. PMID 10754681.

- ↑ Carreira, E. M.; Fettes, A.; Martl, C. (2006). "Catalytic Enantioselective Aldol Addition Reactions". Org. React. 67: 1–216. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or067.01. ISBN 0471264180.

- ↑ Z. G. Hajos, D. R. Parrish, German Patent DE 2102623 1971

- ↑ Hajos, Zoltan G.; Parrish, David R. (1974). "Asymmetric synthesis of bicyclic intermediates of natural product chemistry". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 39 (12): 1615–1621. doi:10.1021/jo00925a003.

- ↑ Eder, Ulrich; Sauer, Gerhard; Wiechert, Rudolf (1971). "New Type of Asymmetric Cyclization to Optically Active Steroid CD Partial Structures". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 10 (7): 1615–1621. doi:10.1002/anie.197104961.

- ↑ List, Benjamin (2006). "The ying and yang of asymmetric aminocatalysis". Chemical Communications (8): 819–824. doi:10.1039/b514296m. PMID 16479280.

- ↑ Northrup, Alan B.; MacMillan David W. C. (2002). "The First Direct and Enantioselective Cross-Aldol Reaction of Aldehydes". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 124 (24): 6798–6799. doi:10.1021/ja0262378. PMID 12059180.

- ↑ Northrup A. B.; Mangion I. K.; Hettche F.; MacMillan D. W. C. (2004). "Enantioselective Organocatalytic Direct Aldol Reactions of -Oxyaldehydes: Step One in a Two-Step Synthesis of Carbohydrates". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 43 (16): 2152–2154. doi:10.1002/anie.200453716. PMID 15083470.

- ↑ Evans, D. A.; Tedrow, J. S.; Shaw, J. T.; Downey, C. W. (2002). "Diastereoselective Magnesium Halide-Catalyzed anti-Aldol Reactions of Chiral N-Acyloxazolidinones". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 124 (3): 392–393. doi:10.1021/ja0119548. PMID 11792206.

- ↑ Evans, David A.; Downey, C. Wade; Shaw, Jared T.; Tedrow, Jason S. (2002). "Magnesium Halide-Catalyzed Anti-Aldol Reactions of Chiral N-Acylthiazolidinethiones". Organic Letters. 4 (7): 1127–1130. doi:10.1021/ol025553o. PMID 11922799.

- ↑ Magdziak, D.; Lalic, G.; Lee, H. M.; Fortner, K. C.; Aloise, A. D.; Shair, M. D. (2005). "Catalytic Enantioselective Thioester Aldol Reactions That Are Compatible with Protic Functional Groups". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (20): 7284–7285. doi:10.1021/ja051759j. PMID 15898756.