Fall Creek massacre

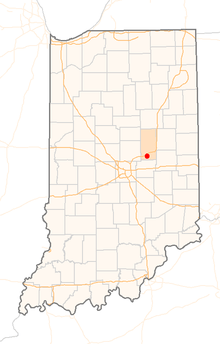

The Fall Creek massacre refers to the slaughter of 9 Native Americans—two men, three women, two boys, and two girls—of uncertain tribal origin on March 22, 1824 by seven white settlers in Madison County, Indiana. The tribal band was living in an encampment along Deer Lick Creek, near the falls at Fall Creek, the site of present-day Pendleton, Indiana. The incident sparked national attention as details of the massacre and trial were reported in newspapers of the day. It was the first documented case in which white Americans were convicted, sentenced to capital punishment, and executed for the murder of Native Americans under U.S. law. Of the seven white men who participated in the crime, six were captured. The other white man, Thomas Harper, was never apprehended. Four of the men were charged with murder and two testified for the prosecution. The four accused men were convicted and sentenced to death by hanging. James Hudson was hanged on January 12, 1825, in Madison County, and Andrew Sawyer and John Bridge Sr. were hanged on June 3, 1825. James B. Ray, the governor of Indiana, pardoned John Bridge Jr., the eighteen-year-old son of John Bridge Sr., due to his age and the influence the others may have had on his involvement in the murders.

Few details about the victims are known. The white men knew the Native American men only as Ludlow and Logan. The names of the remaining victims were not recorded. It is possible that the band had a mixed tribal background of Seneca, Shawnee, and Delaware, which was not unusual in the tribes of the region. John Johnson, a federal Indian agent, identified them as a band of Seneca who had come to the area as part of their winter migration from their home base near Lewis Town, Ohio.

In spite of the case's notoriety and the convictions of the white perpetrators, the massacre did not set a lasting precedent for equal justice under American law. A stone marker in Pendleton's Fall Creek Park commemorates the site of the hangings. A state historical marker along State Road 38 in rural Madison County, close to present-day Markleville, Indiana, identifies the nearby site of the murders. The events also served as the inspiration for The Massacre at Fall Creek, a novel by Jessamyn West, which was published in 1975.

Prior events

Sometime between November 1823 and February 1824, a small party of Indians came to the area along Deer Lick Creek, near the present-day town of Pendleton, Indiana, in Madison County, to hunt, trap, gather furs, and collect maple syrup.[1][2] The band included three men known to local whites as Logan, Ludlow, and M'Doal (or Mingo), three women, two boys, and two girls.[3][4] Their tribal origins remain a mystery, although some sources connected to the case, such as the Federal Indian agent, John Johnston, describe them as a mixed band of Seneca and Shawnee from their home village of Lewis Town in northwest Ohio, approximately one hundred miles to the east.[1][5] Other, slightly later sources, suggest the band included Delaware, Miami, and mixed-race members having some European ancestry. Bands with remnant members from numerous tribes in the Old Northwest were quite common at this time, but the precise ethnic backgrounds of this particular group's members will never be known.[6] They established their camp in Madison County, near a village of white settlers with whom they could trade their goods.[5]

Sources reporting the massacre's events suggest the white settlers had developed a friendly relationship with the band, which was headed by Chief Logan, a "venerable old chief" and "a friend of the white men";[7] however, historians have proposed that tensions were growing between Ludlow and some of the settlers, most notably James Hudson, Thomas Harper, and John T. Bridge Sr., in the days leading up to the attack.[8] Hudson alleged that he had encountered Ludlow several days prior to the massacre and heard him threaten to kill any white man who disturbed his animal traps. He also accused Ludlow of threatening to harm his wife after she refused to trade with Ludlow several days prior to the attack.[9] Bridge Sr. and Harper had also visited the camp a few days prior to the attack. Hudson later acknowledged that three days prior to the massacre he thought Bridge intended to poison the Native Americans, but decided did not proceed with the idea. Hudson also reported that Ludlow became angry after a dog he had purchased from Harper was later taken away from him.[10]

More details are known about the background of the victims' attackers. Hudson, who was originally from Baltimore County, Maryland, moved to Kentucky as a boy and later migrated to Ohio before settling with his wife, Phoebe, and their family in Madison County.[11][12] Harper, a wandering frontiersman who drifted from Butler County, Ohio, into Madison County early in 1824, was an obsessive Indian-hater.[13] Native Americans kidnapped his three-year-old sister, Elizabeth, in 1800, and killed his brother, James, during the War of 1812.[14] Harper was also the brother-in-law of John T. Bridge Sr., who was born in Boston, Massachusetts, and moved to Ohio before migrating to Indiana with his wife, Mary Harper, and their children in 1819. Mary died two years later and Bridge Sr. may have married the sister of a neighbor named Andrew Sawyer, who was also involved in the massacre; however, this has not been confirmed. Little is known of Sawyer's family background.[15]

On Friday, March 19, 1824, when several local settlers gathered for a house-raising, Harper, Hudson, Sawyer, and others began discussing the Indian presence in the area. The conversation became heated as the men drank liquor and boasted that they would kill any Indian who stole their property or threatened a settler's wife.[16] On Sunday, March 21, the day before the attack, Sawyer came to the Hudson farm to report that two of his horses were missing and asked for help in recapturing them. Harper and Sawyer; Sawyer's son, Stephen; John T. Bridge, Sr.; his two sons, James and 18-year-old John Bridge, Jr.; and a boy named Andrew Jones went on an unsuccessful search for the horses.[17][18] The men gathered at the Sawyer cabin the following morning to continue the search.[17] During this time Hudson began to suspect that Harper had convinced Sawyer to harm the small group of Native Americans living hear Deer Lick Creek, even if they had not been involved in the horse theft.[19]

The massacre

The white men approached the band on March 22, 1824.[20] There were just two men in camp with the women and children at the time of their arrival. M'Doal had gone to check his animal traps before the men arrived.[21] Hudson and Sawyer asked Logan and Ludlow for help in tracking the two horses that had escaped from Harper's farm. The two men agreed to help for an agreed upon fee of fifty cents each,[17] and walked with the white men toward the woods, joking as they went.[22] The white men, who had been drinking heavily for several days, were heavily armed with knives and rifles.[21] After a brief stop at an abandoned cabin, where several of the men drank more liquor, the party divided into two groups and continued into the woods. Logan joined Hudson, Bridge Jr., and Jones, while Ludlow went in a different direction with Harper, Andrew and Stephen Sawyer, and James Bridge. James left the group for unknown reasons and was replaced by his father, John Bridge Sr.[23] As Logan moved ahead, the three white men in his group fell behind and Hudson shot him in the back. Bridge Jr. struck Logan in the head with his rifle and stabbed him before the men hid his body in the woods. In the meantime, Harper shot Ludlow in the back as the others in his group watched. Ludlow's body was never recovered.[24]

The men, with the exception of Hudson, returned to the camp, where they murdered the three women and four children. M'Doal, who was not in camp when they arrived, witnessed the killings as he returned. Although he may have been wounded by gunfire, M'doal escaped into the woods and was never found.[25][7] In all, Harper's party killed nine people: two men, three women, and four children. The men also stole everything of value before leaving the Indian camp and returning to their farms.[26]

Reports of gunfire, the sudden disappearance of the nearby Indians, and conversations that neighbors overheard in the Sawyer and Bridge homes prompted a search party to begin an investigation the following morning.[27] John Adams, a neighbor boy who was staying overnight at the Bridge cabin, overheard the men when they returned home the night of the murders. Bridge Sr. sent the boy home and asked him to return with his father, a local farmer named Abraham Adams, to help search for Sawyer's missing horses. Adams also told his father what he had overheard.[28] Adams and his son went to the Sawyer farm, where they met Bridge Sr., two of Bridge's sons, and Harper. Sawyer informed the men that the horses had come home on their own, but he reported hearing gunfire at the camp. The men went to investigate. Adams realized that the abandoned camp was the scene of the murder after the bodies were discovered nearby.[29] The men also found that one of the women, although injured, had survived the attack, but was unable to clearly explain what had happened. The group left her at the scene and rode off to report it.[22] On Wednesday, March 24, two days after the attack, a second group of men arrived at the camp to find her still alive. They also located Logan's body and buried him at the scene.[30] The surviving woman was taken to a settler's farm, but the owner refused to let her stay, so she was taken to the Bridge's cabin, where she died later that day.[31]

On Thursday, March 25, within three days of the killings, the authorities arrived to arrest Harper, Bridge Sr., and Bridge Jr.; however, Harper escaped into the woods. Hudson, Jones, and both Sawyer men were arrested shortly thereafter.[32] Within a week they were all in custody, with the exception of Harper, who had taken the stolen goods and fled.[33] He was never captured.[34] Following their arrest Hudson, Bridge Sr., Bridge Jr., and Andrew Sawyer were chained in Madison County's newly built log jail until their trials. Andrew Jones and Stephen Sawyer, who remained free on bond, and John Adams turned state's evidence in the upcoming trials.[34][35]

News of the crime spread quickly, and settlers feared retribution from Native Americans living in the local Delaware villages. Native American customs at the time also called for monetary compensation to the victims' families.[36] While the accused men awaited trial, William Conner, a trusted frontiersman, interpreter, and community leader, and John Johnston, and Indian agent residing in Piqua, Ohio, at that time, traveled to the local Indian villages to talk with the people.[37] Johnston and Conner, whose intent was to maintain order, calmed the fears of the white settlers and assured the Native Americans that the men who had attacked their people had been caught and the government would seek justice for their murders.[38] The two men's efforts were successful, and no violence erupted. The threat of retaliation for the murders subsided, but no one knew how long the peace would last.[39]

Trials and executions

The four men who had been arrested were tried in Madison County Court. Seven of the state's top lawyers were hired to defend them. It is unclear whether the men paid for their own legal fees or others paid all or part of their defense. The two lead defense attorneys were Calvin Fletcher and Martin M. Ray, a brother of James Brown Ray, the governor of Indiana.[40] The other defense lawyers were Bethuel F. Morris, William R. Morris, Lot Bloomfield, Charles H. Test, and James Rariden.[41] U.S. Senator James Noble was appointed as special prosecutor to assist two local attorneys, James Gilmore and Cyrus French. Noble selected Harvey Gregg and Philip Sweetser to assist him.[42] Hudson, Bridge Sr., Bridge Jr., and Andrew Sawyer were indicted on April 8, 1824; however, their trials were postponed until October 1824, due to the illness of the circuit court's lead judge, William Wick.[43] While awaiting trial, the prisoners escaped from the county jail on more than one occasion, but were quickly recaptured.[44]

The Fifth Judicial Circuit Court of Indiana opened in Madison County on October 7, 1824. At that time state law allowed the court only three days to complete its work before adjourning the session.[45] The cases were tried before a three-member circuit court panel, which consisted of Wick, Samuel Holliday, and Adam Winsell.[46] Following the conclusion of other court business, a twelve-member jury was seated for the trials, which generated nationwide attention.[45] The following morning, James Hudson was tried first. Andrew Jones was a key witness for the prosecution; however, the defense called no witnesses on Hudson's behalf.[47] The jury deliberated only an hour before finding Hudson guilty.[48] Some people were surprised by the verdict. Hudson was sentenced to death by hanging, with an execution date set for December 1, 1824.[49] It was the first time any white man in the United States had been sentenced to capital punishment for killing a Native American.[18][50] The trials for the other three men were postposed.[48]

Hudson appealed to the Supreme Court of Indiana, then in session at Corydon, Indiana. The court issued an opinion on November 13, 1824, written by Chief Justice Isaac Blackford that upheld the lower court's decision and rejected all points of Hudson's appeal.[7] Two days later, Hudson escaped from jail and hid beneath the floor of a vacant cabin, where he suffered from frostbite and dehydration. He was recaptured ten days later, when he came out of hiding to find water and was returned to the Madison County jail. While he was missing, the execution date was rescheduled for the following January.[50] On January 12, 1825, a large crowd, which reportedly included several Seneca and Shawnee, gathered to witness the historic execution. The condemned man had to be carried to the gallows due to the frostbite he had suffered while in hiding.[7] Hudson was interred in a nearby cemetery, north of the falls at Fall Creek.[51]

The trials of the remaining three men, Bridge Sr., Bridge Jr., and Andrew Sawyer, began on May 9, 1825, in the Third Judicial Circuit Court in Madison County. Miles C. Eggleston replaced Wick as one of the three presiding judges. Oliver H. Smith was the chief prosecutor and James Rariden led the defense team. After fifteen hours of deliberation, the jury reached a verdict in Sawyer's case. He was found guilty of manslaughter, not murder, for killing one of the women. His punishment was two years in prison and a fine of one hundred dollars.[52] Bridge Jr. who faced two murder charges in Logan's death, was tried next. The jury found him guilty after three hours of deliberation on both counts; however, they recommended a pardon for the teenager due to the influence of his father and uncle. The jury took only a few minutes to return a guilty verdict for Bridge Sr.[53] To conclude the trials Andrew Sawyer was tried and found guilty of murder.[54] A petition on behalf of Bridge Jr. was signed by ninety-four locals, including many members of the jury, the county clerk, several attorneys, two prison guards, and a minister, and submitted to Governor James Brown Ray.[55] The petition requested a pardon and cited "his youth, ignorance, and the manner which he was led into the transaction." By the appointed date of execution, it had not been answered.[18]

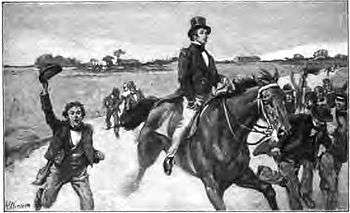

On June 3, 1825, another large crowd, including numerous Native Americans, gathered for the executions, which were conducted one at a time. Sawyer was hanged first, followed by the execution of Bridge, Sr. His eighteen-year-old son, John Bridge Jr., witnessed both hangings before being led to the gallows and fitted with a noose and hood. At that point, Governor Ray, who had arrived on horseback, moved through the crowd and stopped the execution. After presenting the pinioned teenage prisoner with a written pardon, the governor announced, "Here is your pardon. Go sir, and sin no more."[56] The young prisoner was immediately set free.[57] A Seneca chief in attendance at the hangings and the dramatic pardon remarked, "We are satisfied."[58]

Aftermath

Furor over the massacre quickly subsided following the trials and hangings of Hudson, Bridge Sr., and Sawyer. The village at the falls of Fall Creek soon faded from the public spotlight and settlers continued to move into the area.[59] Johnston returned to his home in Ohio. The defense and prosecuting attorneys went on to achieve political success. Oliver H. Smith was elected to Congress and James Brown Ray was re-elected as governor.[60] Thomas Harper, the ringleader of the murderers, was never apprehended. It is not known what happened to Andrew Jones and Stephen Sawyer. John Bridge Jr. returned to his home in Butler County, Ohio, where he worked as a farmer. In 1824 he settled in Carroll County, Indiana, where he became a dry goods merchant. He died at Delphi, Indiana, in 1876.[61]

The prosecutions of the white men for the murders of the Native Americans, which cost the United States government nearly seven thousand dollars, avoided further disruptions in the area.[59] Removal of native tribes from the area east of the Mississippi River continued, as did white settlement along the White River.[61] The guilty verdict from the white jury "remained an extreme anomaly".[62] Other acts of violence between whites and native tribes occurred in the decades that followed; however, the events at Fall Creek set a precedent with the trials that recognized the civil rights of Native Americans in a court of law.[62]

Complete details of all the related events remain unknown. The original transcripts of the trials were destroyed in a fire at the Madison County courthouse in 1880, and details gathered from the surviving sources leave behind an incomplete record of conflicting information and disputes over the accuracy of the reports. Two official documents incorrectly recorded that the massacre occurred on April 20, 1824.[63] No written accounts from the victims or other Native Americans living in the area at the time were recorded, and none were called to testify in the legal proceedings.[64] The events near present-day Pendleton, Indiana, remains a part of the area's local history, despite a lack of detailed records, inaccuracies among the sources, and its disappearance from recollections of national events.[65] It also inspired a fictional account of the events in Jessamyn West's novel, The Massacre at Fall Creek, published in 1975.[66]

Memorials

In Fall Creek Park in Pendleton, Indiana, a stone marker reads: "Three white men were hung here in 1825 for killing Indians."[67] In 1991 the Pendleton Historic District, which includes the park and this historical marker, was named to the National Register of Historic Places.[68]

In 1966 the Indiana Sesquicentennial Commission erected an historic highway marker noting the incident along State Route 38, one-half mile east of Markleville, Madison County. It reads: "In 1824, nine Indians were murdered by white men near this spot. The men were tried, found guilty and hanged. It was the first execution of white men for killing Indians."[69][70]

Notes

- 1 2 Doerr 1997, p. 20.

- ↑ David Thomas Murphy, Murder in Their Hearts: The Fall Creek Massacre, p. 7–8, suggests they arrived in the fall of 1823, about four months before the massacre occurred, while John Johnston, Recollections of Sixty Years, p. 162, in Johnston and the Indians in the Land of the Three Miamis, edited by Leonard U. Hill; J. J. Netterville, ed., Centennial History of Madison County Indiana: An Account of One Hundred Years of Progress, 1823-1923, vol. I, p. 71; and Harold Allison, The Tragic Saga of the Indiana Indians, p. 267, indicate an arrival in the late winter of 1824.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 7—8.

- ↑ Doerr 1997, p. 19.

- 1 2 Murphy 2010, p. 25.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 18–24.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Fall Creek Massacre". Conner Prairie. Retrieved 2012-04-16.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 55.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 56–57.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 58 and 59.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 56.

- ↑ Doerr 1997, p. 23.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 39.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 40.

- ↑ Doerr 1997, p. 22 and 23.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 60.

- 1 2 3 Doerr 1997, p. 24.

- 1 2 3 Allison 1986, p. 270.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 61.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 7.

- 1 2 Murphy 2010, p. 8.

- 1 2 Allison 1986, p. 268.

- ↑ Doerr 1997, p. 25 and 26.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 10 and 11.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 12 and 13.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 14.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 37.

- ↑ Doerr 1997, p. 27.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 67 and 68.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 68 and 69.

- ↑ Doerr 1997, p. 28.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 71.

- ↑ Allison 1986, p. 269.

- 1 2 Doerr 1997, p. 30.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 80, 88–89.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 72.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 78, 81, and 83.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 78–81.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 84.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 89–91.

- ↑ Doerr 1997, p. 34.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 93.

- ↑ Doerr 1997, p. 33.

- ↑ Doerr 1997, p. 35.

- 1 2 Doerr 1997, p. 36.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 88.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 97.

- 1 2 Doerr 1997, p. 37.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 98.

- 1 2 Funk 1983, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 103.

- ↑ Doerr 1997, p. 41.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 106–7.

- ↑ Doerr 1997, p. 42.

- ↑ Doerr 1997, p. 43.

- ↑ Netterville 1925, p. 79.

- ↑ Allison 1986, p. 271.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 112.

- 1 2 Doerr 1997, p. 46.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 113.

- 1 2 Murphy 2010, p. 114.

- 1 2 Murphy 2010, p. 115.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 1–3.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 3.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 116.

- ↑ Murphy 2010, p. 1.

- ↑ "Three White Men Were Hung Here". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ↑ Laura Thayer (1991-04-30). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Pendleton Historic District" (PDF). Indiana Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 2014-04-30. See Section 7, p. 9, and Section 8, p. 1 and 2.

- ↑ "Massacre of Indians". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ↑ "Massacre of Indians". Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

References

- Allison, Harold (1986). The Tragic Saga of the Indiana Indians. Paducah: Turner Publishing Company. Graphic Design of Indiana. ISBN 0-938021-07-9.

- Doerr, Brian (March 1997). "The Massacre at Deer Lick Creek, Madison County, Indiana, 1824". Indiana Magazine of History. Bloomington, Indiana. 93 (1): 19–47. JSTOR 27791980.

- Funk, Arville (1983) [1969]. A Sketchbook of Indiana History. Rochester, Indiana: Christian Book Press.

- Johnston, John (1957). "Recollections of Sixty Years." In John Johnston and the Indians in the Land of the Three Miamis. Edited by Leonard U. Hill. Piqua, OH: Stoneman Press.

- Murphy, David Thomas (2010). Murder in Their Hearts: The Fall Creek Massacre. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press.

- West, Jessamyn (1975). The Massacre at Fall Creek (fiction). New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 0151578206.

- Netterville, J. J., ed. (1925). Centennial History of Madison County Indiana: An Account of One Hundred Years of Progress, 1823-1923. I. Anderson, IN: Historians’ Association. p. 70–79.