Female hysteria

| Female hysteria | |

|---|---|

|

Women with hysteria under the effects of hypnosis | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

Female hysteria was a once-common medical diagnosis, reserved exclusively for women, which is today no longer recognized by medical authorities as a medical disorder. Its diagnosis and treatment were routine for many hundreds of years in Western Europe.[1] Hysteria of both genders was widely discussed in the medical literature of the nineteenth century. Women considered to have it exhibited a wide array of symptoms, including faintness, nervousness, sexual desire, insomnia, fluid retention, heaviness in the abdomen, shortness of breath, irritability, loss of appetite for food or sex, and a "tendency to cause trouble."[2]

In extreme cases, the woman might be forced to enter an insane asylum or to undergo surgical hysterectomy.[3]

Early history

The history of the notion of hysteria can be traced to ancient times; in ancient Greece it was described in the gynecological treatises of the Hippocratic corpus, which date from the 5th and 4th centuries BC. Plato's dialogue Timaeus compares a woman's uterus to a living creature that wanders throughout a woman’s body, "blocking passages, obstructing breathing, and causing disease."[4] The concept of a pathological, wandering womb was later viewed as the source of the term hysteria,[4] which stems from the Greek cognate of uterus, ὑστέρα (hystera).

Another cause was thought to be the retention of a supposed female semen, thought to mingle with male semen during intercourse. This was believed to be stored in the womb. Hysteria was referred to as "the widow's disease," since the female semen was believed to turn venomous if not released through regular climax or intercourse.[5]

Nineteenth century

A physician George Taylor in 1859 claimed that a quarter of all women suffered from hysteria. George Beard, a physician catalogued seventy-five pages of possible symptoms of hysteria and called the list incomplete;[6] almost any ailment could fit the diagnosis. Physicians thought that the stresses associated with modern life caused civilized women to be both more susceptible to nervous disorders and to develop faulty reproductive tracts.[7] In the United States, such disorders in women reaffirmed that the US was on par with Europe; one American physician expressed pleasure that the country was ”catching up” to Europe in the prevalence of hysteria.[6]

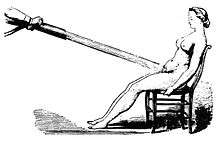

Rachel Maines hypothesized that doctors from the classical era until the early 20th century commonly treated hysteria by masturbating female patients to orgasm (termed 'hysterical paroxysm'), and that the inconvenience of this may have driven the early development of and market for the vibrator.[8] Although Maines's view that masturbating female patients to orgasm was used to treat hysteria is widely repeated in the literature on female anatomy and sexuality,[9] some historians dispute Maines's claims about the prevalence of this treatment for hysteria and about its relevance to the invention of the vibrator, describing them as a distortion of the evidence or only relevant to an extremely limited group.[10][11][12] Maines has said that her theory should be treated as a hypothesis rather than a fact.[9]

Decline

During the early twentieth century, the number of women diagnosed with female hysteria declined sharply. This decline has been attributed to many reasons. Some medical authors claim that the decline was due to laypeople gaining a greater understanding of the psychology behind conversion disorders such as hysteria.[13]

With so many possible symptoms, hysteria was always considered a catchall diagnosis where any unidentifiable ailment could be assigned. As diagnostic techniques improved, the number of ambiguous cases that might have been attributed to hysteria declined. For instance, before the introduction of electroencephalography, epilepsy was frequently confused with hysteria.[14] Many cases that had previously been labeled hysteria were reclassified by Sigmund Freud as anxiety neuroses.[14]

Today, female hysteria is no longer a recognized illness, but different manifestations of hysteria are recognized in other conditions such as schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder, conversion disorder, and anxiety attacks.

See also

- Hysterical contagion

- Mass psychogenic illness

- Mass hysteria

- Conversion disorder

- Male hysteria

- Vapours (disease)

References

- ↑ Rachel P. Maines (1999). The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria", the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6646-4.

- ↑ Maines, Rachel P. (1998). The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria", the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6646-4.

- ↑ Mankiller, Wilma P. (1998). The Reader's Companion to U.S. Women's History. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co. p. 26. ISBN 0-6180-0182-4.

- 1 2 King, Helen (1993). "Once upon a text: Hysteria from Hippocrates". In Gilman, Sander; King; Porter, Helen; Rousseau, G.S.; Showalter, Elaine. Hysteria beyond Freud. University of California Press. pp. 3–90. ISBN 0-520-08064-5.

- ↑ Roach, Mary (2009). Bonk: the curious coupling of science and sex. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. p. 214. ISBN 9780393334791.

- 1 2 Briggs, Laura (2000). "The Race of Hysteria: "Overcivilization" and the "Savage" Woman in Late Nineteenth-Century Obstetrics and Gynecology". American Quarterly. 52 (2): 246–73. doi:10.1353/aq.2000.0013. PMID 16858900.

- ↑ Morantz, Regina M.; Zschoche, Sue (1980). "Professionalism, Feminism, and Gender Roles: A Comparative Study of Nineteenth-Century Medical Therapeutics". The Journal of American History. 67 (3): 568–88. doi:10.2307/1889868. JSTOR 1889868. PMID 11614687.

- ↑ Maines, Rachel P. (1999). The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6646-3.

- 1 2 Maines, Rachel. "Big Think Interview With Rachel Maines". bigthink.com. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ↑ King, Helen (2011). "Galen and the widow: towards a history of therapeutic masturbation in ancient gynaecology" (PDF). EuGeStA: Journal on Gender Studies in Antiquity. 1: 205–235.

- ↑ Hall, Lesley. "Doctors masturbating women as a cure for hysteria/'Victorian vibrators'". lesleyahall.net. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ↑ Riddell, Fern (10 November 2014). "No, no, no! Victorians didn't invent the vibrator". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- 1 2 Micale, Mark S. (1993). "On the "Disappearance" of Hysteria: A Study in the Clinical Deconstruction of a Diagnosis". Isis. 84 (3): 496–526. doi:10.1086/356549. PMID 8282518.

- 1 2 Micale, Mark S. (July 2000). "The Decline of Hysteria". Harvard Mental Health Letter. 17 (1): 4–6. PMID 10877868.

Further reading

- Libbrecht, Katrien (1995). Hysterical Psychosis: A Historical Survey. London: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-181-X.

- Micale, Mark S. (1995). Approaching Hysteria: Disease and its Interpretations. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03717-5.

- Micale, Mark S. (2009-06-30). Hysterical Men: The Hidden History of Male Nervous Illness. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674040984.

- Micklem, Niel (1996). The Nature of Hysteria. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-12186-8.

- Bronfen, Elisabeth (2014-07-14). The Knotted Subject: Hysteria and Its Discontents. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400864737.

- Augsburg, Tanya (1996). Private Theatres Onstage (Hysteria and the Female Medical Subject). UMI.

External links

- Is Hysteria Real? Brain Images Say Yes by Erika Kinetz in The New York Times

- Female Hysteria during Victorian Era