Finnish–Russian border

The Finnish–Russian border is the roughly north/south international border between Finland and Russia. Some 1,340 km (833 miles) long,[1] it runs mostly through uninhabited taiga forests and sparsely populated rural areas, not following any particular natural feature or river.[2] It is also part of the external border of both the Schengen Area and the European Union.

Border crossings are controlled and patrolled by the Finnish Border Guard and Border Guard Service of Russia, who also enforce border zones (0.1–3 km on the Finnish side,[3] at least 7.5 km on the Russian side). Entry to a border zone requires a permit. The electronic surveillance on the Finnish side is concentrated most heavily on the "southernmost 200 kilometers" and is constantly growing in sophistication.[4] The Finnish Border Guard conducts "regularly irregular" K9 patrols to catch anyone venturing into the border zone. Russia maintains its 500-year-old border patrol in the arctic region as elsewhere and plans to upgrade Soviet border technologies to both save on cost and to fully maximize the efficiency of the Border Service by the year 2020. But Lieutenant-General Vladimir Streltsov, deputy head of the Russian border service, noted that electronic surveillance will never replace the human element.[5]

The border can be crossed only at official checkpoints, and at least one visa is required for most people. Major border checkpoints are found in Vaalimaa and Nuijamaa, where customs services on both sides inspect and levy fees on imported goods.

The northern endpoint of the border between Norway, Finland, and Russia form a tripoint marked by Treriksrøysa, a stone cairn near Muotkavaara (69°03′06″N 28°55′45″E / 69.05167°N 28.92917°E). On the south, the boundary is on the shore of Gulf of Finland, in which there is a maritime boundary between the respective territorial waters, terminating in a narrow strip of international waters between Finnish and Estonian territorial waters.[6][7]

History

Sweden-Russia border

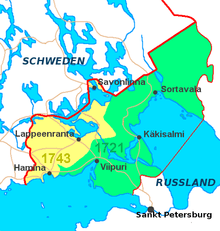

The first border treaty concerning this border was signed in Nöteborg in 1323, between Sweden (to which Finland belonged) and the Novgorod Republic. The Treaty of Teusina in 1595 moved the border eastbound. In conclusion to the Ingrian War, Sweden gained a large tract of land through the acquisition of the Nöteborg fortress, the Kexholm and its large province, southwest Karelia and the province of Ingria in the Treaty of Stolbovo (1617). The Treaty of Nystad in 1721 and the Treaty of Åbo in 1743 moved the border westward.

The main difference between the different sides of the border at the time was religion. The Russian side was Russian Orthodox, the Swedish side was Catholic, later Lutheran Protestant. Generally the native population was ethnically Finnish and Finnish-speaking immediately on both sides of the border. However, after the peace of Stolbovo in 1617, the Orthodox population was persecuted and either fled to Tver or converted to Lutheranism and started speaking Finnish instead of the closely related Karelian. The population was largely replaced by immigrants from Finland, most of which were Savonians.

Internal Russian border

After the Finnish War, the Treaty of Fredrikshamn converted all of Finland from Swedish territory to a Russian possession, the Grand Duchy of Finland. The Finnish–Russian border was moved back to the pre-1721 location, so that the Grand Duchy gained the so-called "Old Finland", territories previously held by Sweden, in 1812.

Finland-Soviet Russia border

After Finland became independent in 1917, there was the Finnish Civil War in 1918, and even after this war, the Russian Civil War continued. Finnish activists often crossed the border into Soviet territory in order to fight in the "heimosodat", wars aiming at Finnish ethnic self-determination and possible annexation into Finland. However, this came to an end in 1920, when the Russian/Finnish Treaty of Tartu in 1920 defined Finland as independent and demarcated the countries' common border. However, Finnish fighters would still take part in the East Karelian uprising and Soviet–Finnish conflict of 1921–22. Finally, the Finnish government closed the border from the volunteers and food and munitions shipments in 1922.

Changes to borders with World War II

During World War II, Stalin severely suppressed the native Finnish-speaking population (Ingrian Finns) by population transfers, collectivization and purges, such that border zones were to be free of Finnish peoples.

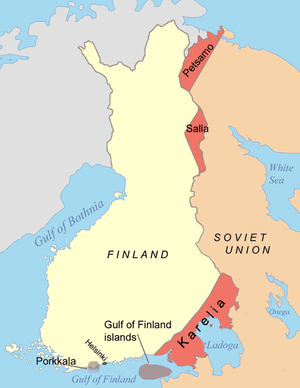

The land border was later demarcated in the Treaty of Paris (1947) following the Continuation War (1941–44), in which Finnish Karelia, including Finland's second-largest city Viipuri, parts of Salla and Petsamo were ceded to the Soviet Union. The new border cut through Finnish territory proper, severing many rail lines and isolating many Karelian towns from Finland. The Soviet Union demanded emptying the territories first. Finns were evacuated from the area and resettled elsewhere in Finland; almost nobody was willing to stay. The areas were resettled by Soviet immigrants. The Porkkala naval base was leased by the Soviet Union, but returned to the Finnish government in 1956. The naval border was established in 1940 and more accurately defined in 1965.

The border is uncontroversial and clearly defined by law.[8] Both states verified the inviolability of borders and territorial integrity in the first Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe in 1975.

Soviet-Finnish border during the Cold War

During the Cold War, the border constituted part of the perimeter of the Iron Curtain. Crossing the border was not possible for much of its length. Only a very limited number of border crossing points existed, and the Soviet government permitted only escorted trips to select cities; border zones were off limits to tourists.[9] There was little contact between cities that were relatively close to each other on opposite sides of the border, such as Imatra and Svetogorsk. On the Finnish side, there was a border zone where entry was allowed only with a permit, but habitation was permitted and residents could continue living in the area. The Soviet side had extensive electronic systems and patrols to prevent escapes. Soviet border surveillance began at a great distance from the actual border, and was as extensive as elsewhere along the Iron Curtain. The first surveillance was already in railway stations in cities, where the militsiya monitored potentially suspicious traffic. The border zone began at 120 km from the border. A special permit was required for entry, and there was the first line of control with electronic alarms. At 60 km, there was a raked sand strip (to detect footprints) and a thin alarmed tripwire. At 20 km, there was a three-meter barbed wire fence, with a top that curved inwards towards Soviet territory. The fence had an electronic alarm system. However, it was not protected underground and tunnelling under it was possible. Finally, at the international border, there was a border vista. In the north, this was followed by a Finnish reindeer fence. However, unlike in the West proper, the government of Finland did not protect illegal border crossers but returned them to the Soviet authorities if captured. Illegal border crossers had to get through Finland to e.g. Sweden in order to defect to the West.[9]

In the Moscow Armistice signed on 1944 between Finland, Soviet Union and United Kingdom, a small peninsula towards the Gulf of Finland, Porkkala, was rented to Soviet Union as a military base. This created in effect a southern border crossing to the Soviet exclave, operating all the way to 1956. Border crossings were in Luoma (checkpoint) and Tähtelä. In 1947, Finnish trains were allowed to pass through the base, but the passenger car windows were blinded and locomotive replaced while crossing through. Earlier between 1940–41, Soviet Union had rented Hanko Peninsula, Hangon vuokra-alue, as a military base. Apparently there was also a border crossing to the exclave at the time.

Traffic

In 2015, 9.1 million individuals crossed the border, half of which through Vaalimaa and Nuijamaa.[10]

Finland is the country that issues the most Schengen visas to Russians.[11]

Incidents

On 26 November 1939, the Soviet Union's Red Army shelled the Russian village of Mainila, and blamed Finland. The Soviets used this false flag operation as the pretext to start the Winter War a few days later.

According to a Russian media report, Finland closed its Raja-Jooseppi border crossing with Russia, a counterpart to the Russian Lotta (checkpoint) border post, on 4 December 2015, an hour and a half before the day's scheduled closing time and thus prevented fifteen people of Mid-East origin from crossing the border. According to the same source, some Finnish border officials confirmed that Raja-Jooseppi had closed early that day while a spokesman for the same department said the checkpoint closed at its regular time of 2100 hours. Note the time zone difference between the checkpoints (Eastern European Time and Moscow Time), one hour in winter.

On 27 December 2015, Finland blocked access for people to cross over Russian border on bicycles via Raja-Jooseppi and Salla. According to the Finnish Border Guard, this measure was to limit illegal immigration and ensure safety on slippery roads.[12] The Finnish Border Guard stated that organized traffickers had their clients cross the border by biking in order to avoid being captured on the Finnish side and prosecuted for organizing illegal immigration, which is a felony in Finnish law. In response, asylum seekers started to cross the border by car.[13][14]

On 23 January 2016, Finnish Foreign Minister Timo Soini, member of the Finns Party was reported discussing at the northern border of Salla about inward "people smuggling", and noting that the conclusion that somebody at the Russian side was organizing and regulating the inflow of immigrants was in his mind apparently true. He further noted, that it is imminent that the process is an act of procession.[15] Furthermore, a communal representative of the same Finns Party noted, that the inflow of immigrants causes disturbance for Finns driving to the Russian side to purchase petrol, as the border stays stuck due to immigration proceedings.[16]

In March 2016, Finland and Russia announced that the Raja-Jooseppi border crossing at Inari and the Salla border crossing will be temporarily closed from third country nationals: only Finnish, Russian and Belarusian citizens are allowed to use these crossings for at least 6 months.[17]

List of border checkpoints

From north to south.

- Raja-Jooseppi / Lotta (road 91 / P11 / 47А-059)

- Salla (road 82)

- Kuusamo border station (road 866 / A136)

- Vartius (road 89)

- Vartius (Kontiomäki–Kostomuksha railway, freight only)

- Niirala / Vyartsilya (road 9 / A130)

- Imatra (road 62 / A124)

- Nuijamaa (road 13 / A127)

- Vainikkala (Riihimäki – Saint Petersburg Railway, passenger and freight trains, the only rail crossing used in 2015[18])

- Vaalimaa (road E18 / 7 / M10)

In addition, there are provisional border crossing points:

- Haapovaara

- Inari

- Karttimo

- Kurvinen

- Leminaho

- Parikkala

- Ruhovaara

- Imatra railway crossing point (Imatra–Kamennogorsk railway, freight only)

Of these, only Inari and Parikkala were actually used in 2015.[10]

Passport stamps

The following are Finnish ink passport stamps applied at the Finnish–Russian border.

Passport entry stamp from the Finnish border checkpoint at Imatra

Passport entry stamp from the Finnish border checkpoint at Imatra Passport exit stamp from the Finnish border checkpoint at Imatra

Passport exit stamp from the Finnish border checkpoint at Imatra Passport entry stamp from the Finnish border checkpoint at Nuijamaa

Passport entry stamp from the Finnish border checkpoint at Nuijamaa Passport exit stamp from the Finnish border checkpoint at Vaalimaa

Passport exit stamp from the Finnish border checkpoint at Vaalimaa Passport exit stamp (old style) from the Finnish border checkpoint at Vaalimaa

Passport exit stamp (old style) from the Finnish border checkpoint at Vaalimaa

References

- ↑ Grenfell, Julian; Jopling, Thomas Michael (2008). FRONTEX: the EU external borders agency, 9th report of session 2007-08. House of Lords Stationery Office. p. 13. ISBN 0-1040-1232-3.

- ↑ http://www.eudimensions.eu/content/pstudy/docs/FINLAND%20-%20RUSSIA%20Summary.pdf

- ↑ http://www.raja.fi/ohjeita/rajavyohyke

- ↑ "Electronic surveillance grows at Russian border as border guard strength is cut". HELSINGIN SANOMAT INTERNATIONAL EDITION - HOME. 6 October 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ↑ Borisov, Timofey (28 May 2012). "Shpion v tsifrovom formate". Rossiyskaya Gazeta. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ↑ Svein Askheim. "Treriksrøysa". Store norske leksikon. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Muotkavaara - lines in the wilderness". by-the-borderline.com. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ↑ http://www.uta.fi/FAST/FIN/MIL/ps-surv.html

- 1 2 Timo Laine. Torakoita ja panssarivaunuja - Silminnäkijänä hajoavassa neuvostoimperiumissa. Tammi, Helsinki, 2014.

- 1 2 https://www.raja.fi/tietoa/rajavartiolaitos_lukuina

- ↑ http://barentsobserver.com/en/sections/borders/68-million-people-crossed-finnish-russian-border

- ↑ http://tass.ru/en/world/847182

- ↑ http://www.iltasanomat.fi/kotimaa/art-1451360749593.html

- ↑ http://www.iltasanomat.fi/kotimaa/art-1451360763892.html

- ↑ http://www.iltasanomat.fi/kotimaa/art-1453519718434.html

- ↑ http://www.iltasanomat.fi/kotimaa/art-1453444540265.html

- ↑ http://www.reuters.com/article/us-europe-migrants-finland-russia-idUSKCN0WO32P

- ↑ https://www.raja.fi/tietoa/rajavartiolaitos_lukuina

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Russia-Finland border. |