Finnic languages

| Finnic | |

|---|---|

|

Fennic Baltic Finnic | |

| Ethnicity: | Baltic Finns |

| Geographic distribution: | Northern Fennoscandia, Baltic states, Northwestern Russia |

| Linguistic classification: |

|

| Proto-language: | Proto-Finnic |

| Subdivisions: | |

| Glottolog: | finn1317[1] |

| |

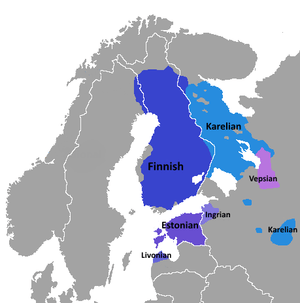

The Finnic (Fennic) or Baltic Finnic (Balto-Finnic, Balto-Fennic) languages[nb 1] are a branch of the Uralic language family spoken around the Baltic Sea by about 7 million people.

Traditionally eight Finnic languages have been recognized.[7] The major modern representatives of the family are Finnish and Estonian, the official languages of their respective nation states.[8] The other Finnic languages in the Baltic Sea region are Ingrian and Votic, spoken in Ingria by the Gulf of Finland; and Livonian, once spoken around Gulf of Riga. Spoken farther northeast are Karelian, Ludic and Veps, in the region of Lakes Onega and Ladoga.

In addition, since the 1990s, several Finnic-speaking minority groups have emerged to seek of recognition as distinct languages, and have established separate literary standard languages.[7] Northern Karelian, Tver Karelian and Livvi represent the three main dialect groups of Karelian, which earlier had been an unwritten language. Võro and Seto (modern descendants of South Estonian) are spoken in southeastern Estonia and earlier were considered dialects of Estonian. The Meänkieli dialects and Kven are spoken in northern Sweden and Norway and have the legal status of independent languages. They were earlier considered dialects of Finnish and are mutually intelligible with it.

The smaller languages are endangered. The last native speaker of Livonian died in 2013, and only about a dozen native speakers of Votic remain. Regardless, even for these languages, the shaping of a standard language and education in it continues.[9]

The geographic centre of the maximum divergence between the languages is located south of the Gulf of Finland.

Classification

The Finnic languages are located at the western end of the Uralic language family. A close affinity to their northern neighbors, the Sami languages has for long been assumed, though many of the similarities (particularly lexical ones) can be shown to result from common influence from Germanic languages and, to a lesser extent, Baltic languages. Innovations are also shared between Finnic and the Mordvinic languages, and in recent times Finnic, Samic and Mordvinic are frequently considered together.

General characteristics

There is no grammatical gender in Finnic languages, nor are there articles nor definite or indefinite forms.[10]

The morphophonology (the way the grammatical function of a morpheme affects its production) is complex. One of the more important processes is the characteristic consonant gradation. Two kinds of gradation occur: the radical and suffix gradation, which affect the plosives /k/, /t/ and /p/.[10] This is a lenition process, where the consonant is changed into a "weaker" form with some (but not all) oblique cases. For geminates, the process is simple to describe: they become simple stops, e.g. kuppi + -n → kupin (Finnish: "cup"). For simple consonants, the process complicates immensely and the results vary by the environment. For example, haka +-n → haan, kyky + -n → kyvyn, järki + -n → järjen (Finnish: "pasture", "ability", "intellect"). (See the separate article for more details.) Vowel harmony (lost in Livonian, generally also in Estonian and Veps) is also an important process. Historically, the "erosion" of word-final sounds (strongest in Livonian, Võro and Estonian) may leave a phonemic status to the morphophonological variations caused by the agglutination of the lost suffixes, which results in three phonemic lengths in these languages.

The original Uralic palatalization was lost in proto-Finnic,[11] but most of the diverging dialects reacquired it. Palatalization is a part of the Estonian literary language and is an essential feature in Võro, as well as Veps, Karelian, and other eastern Finnic languages. It is also found in East Finnish dialects, and is only missing from West Finnish dialects and Standard Finnish.[10]

A special characteristic of the languages is the large number of diphthongs. There are 16 diphthongs in Finnish and 25 in Estonian; at the same time the frequency is greater in Finnish than in Estonian.[10]

There are 14 grammatical cases in Estonian and 15 in Finnish, which are denoted by adding a suffix.

Subgrouping

The Finnic languages form a complex dialect continuum with few clear-cut boundaries.[12] Innovations have often spread through a variety of areas,[4] even after variety-specific changes.

[W]hat can be classified are not the Fennic languages, but the Fennic dialects.— Tiit-Rein Viitso[13]

A broad twofold conventional division of the Finnic varieties recognizes the Southern Finnic and Northern Finnic groups (though the position of some varieties within this division is uncertain):[13]

|

|

† = extinct variety; (†) = moribund variety.

A more-or-less genetic subdivision can be also determined, based on the relative chronology of sound changes within varieties, which provides a rather different view. The following grouping follows among others Sammallahti (1977),[14] Viitso (1998), and Kallio (2014):[15]

- Finnic

- South Estonian (Inland Finnic)

- Coastal Finnic

- Livonian (Gulf of Riga Finnic)

- Gulf of Finland Finnic

The division between South Estonian and the remaining Finnic varieties has isoglosses that must be very old. For the most part, these features have been known for long. Their position as very early in the relative chronology of Finnic, in part representing archaisms in South Estonian, has been shown by Kallio (2007, 2014).[11][15]

| Clusters *kt, *pt | Clusters *kc, *pc (IPA: *[kts], *[pts]) |

Cluster *čk (IPA: *[tʃk]) |

3rd person singular marker | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Estonian | *kt, *pt > tt | *kc, *pc > ts | *čk > tsk | endingless |

| Coastal Finnic | *kt, *pt > *ht | *kc, *pc > *ks, *ps | *čk > *tk | *-pi |

However, due to the strong areal nature of many later innovations, this tree structure has been distorted and sprachbunds have formed. In particular, South Estonian and Livonian show many similarities with the Central Finnic group that must be attributed to later contact, due to the influence of literary North Estonian.[13] Thus, contemporary "Southern Finnic" is a sprachbund that includes these languages, while diachronically they are not closely related.

Viitso (2000)[16] surveys 59 isoglosses separating the family into 58 dialect areas (finer division is possible), finding that an unambiguous perimeter can be set up only for South Estonian, Livonian, Votic, and Veps. In particular, no isogloss exactly coincides with the geographical division into 'Estonian' south of the Bay of Finland and 'Finnish' north of it. Despite this, standard Finnish and Estonian are not mutually intelligible.

Southern Finnic

The Southern Finnic languages consist of North and South Estonian (excluding the Coastal Estonian dialect group), Livonian and Votic (except the highly Ingrian-influenced Kukkuzi Votic). These languages are not closely related genetically, as noted above; it is a paraphyletic grouping, consisting of all Finnic languages except the Northern Finnic languages.[13] The languages regardless share a number of features, such as the presence of a ninth vowel phoneme õ, usually a close-mid back unrounded /ɤ/ (but a close central unrounded /ɨ/ in Livonian), as well as loss of *n before *s with compensatory lengthening.

(North) Estonian-Votic has been suggested to possibly constitute an actual genetic subgroup (called varyingly Maa by Viitso (1998, 2000) or Central Finnic by Kallio (2014)[15]), though the evidence is weak: almost all innovations shared by Estonian and Votic have also spread to South Estonian and/or Livonian. A possible defining innovation is the loss of *h after sonorants (*n, *l, *r).[15]

Northern Finnic

The Northern Finnic group has more evidence for being an actual historical/genetic subgroup. Phonetical innovations would include two changes in unstressed syllables: *ej > *ij, and *o > ö after front-harmonic vowels. The lack of õ in these languages as an innovation rather than a retention has been proposed, and recently resurrected.[15] Germanic loanwords found throughout Northern Finnic but absent in Southern are also abundant, and even several Baltic examples of this are known.

Northern Finnic in turn divides into two main groups. The most Eastern Finnic group consists of the East Finnish dialects as well as Ingrian, Karelian and Veps; the proto-language of these was likely spoken in the vicinity of Lake Ladoga.[14] The Western Finnic group consists of the West Finnish dialects, originally spoken on the western coast of Finland, and within which the oldest division is that into Southwestern, Tavastian and Southern Ostrobothnian dialects. Among these, at least the Southwestern dialects have later come under Estonian influence.

Numerous new dialects have also arisen through contacts of the old dialects: these include e.g. the more northern Finnish dialects (a mixture of West and East Finnish), and the Livvi and Ludic varieties (probably originally Veps dialects but heavily influenced by Karelian).

Salminen (2003) present the following list of Finnic languages and their respective number of speakers.

| Language | Number of speakers | Geographical area |

|---|---|---|

| Livonian | Extinct as first language | Latvia |

| Võro-Seto | 50,000 | Estonia, Russia |

| Estonian | 1,000,000 | Mainly Estonia |

| Votic | 20 | Russia |

| Finnish | 5,000,000 | Mainly Finland |

| Ingrian | 200 | Russia |

| Karelian | 30,000 | Finland, Russia |

| Livvi | 25,000 | Finland, Russia |

| Veps | 5,000 | Russia |

List of Finnic innovations

These features distinguish Finnic languages from other Uralic families:

Sound changes[11][17]

- Development of long vowels and various diphthongs from loss of word-medial consonants such as *x, *j, *w, *ŋ.

- Before a consonant, the Uralic "laryngeal" *x posited on some reconstructions yielded long vowels at an early stage (e.g. *tuxli 'wind' > tuuli), but only the Finnic branch clearly preserves these as such. Later, the same process occurred also between vowels (e.g. *mëxi 'land' > maa).

- Semivowels *j, *w were usually lost when a root ended in *i and contained a preceding front (in the case of *j, e.g. *täji 'tick' > täi) or rounded vowel (in the case of *w, e.g. *suwi 'mouth' > suu).

- The velar nasal *ŋ was vocalized everywhere except before *k, leading to its elimination as a phoneme. Depending on the position, the results included semivowels (e.g. *joŋsi 'bow' > jousi, *suŋi 'summer'> suvi) and full vocalization (e.g. *jäŋi 'ice' > jää, *müŋä 'backside' > Estonian möö-, Finnish myö-).

- The development of an alternation between word-final *i and word-internal *e, from a Proto-Uralic second syllable vowel variously reconstructed as *i (as used in this article), *e or *ə.

- Elimination of all Proto-Uralic palatalization contrasts: *ć, *δ́, *ń, *ś > *c, *δ, *n, *s.

- Elimination of the affricate *č, merging with *š or *t, and the spirant *δ, merging with *t (e.g. *muδ́a 'earth' > muta). See below, however, on treatment of *čk.

- Assibilation of *t (from any source) to *c [t͡s] before *i. This later developed to /s/ widely: hence e.g. *weti 'water' > Estonian and Finnish vesi (cf. retained /t/ in the partitive *wet-tä > Estonian vett, Finnish vettä).

- Consonant gradation, most often for stops, but also found for some other consonants.

- A development *š > h, which, however, postdated the separation of South Estonian.

Superstrate influence of the neighboring Indo-European language groups (Baltic and Germanic) has been proposed as an explanation for a majority of these changes, though for most of the phonetical details the case is not particularly strong.[18]

Grammatical changes

- Agreement of the attributes with the noun, e.g. in Finnish vanho·i·lle mieh·i·lle "to old men" the plural -i- and the case -lle is added also to the adjective.

- Use of a copula verb like on, e.g. mies on vanha "the man is old".

- Grammatical tenses analogous to Germanic tenses, i.e. the system with present, past, perfect and pluperfect tenses.

- The shift of the proto-Uralic locative *-nA and the ablative *-tA into new, cross-linguistically uncommon functions: the former becoming the essive case, the latter the partitive case.

- This resulted in the rise of the telicity contrast of the object, which must be in the accusative case or partitive case.

- The rise of two new series of locative cases, the "inner locative" series marked by an element *-s-, and the "outer locative" marked by an element *-l-.

- The inessive *-ssA and the adessive *-llA were based on the original Uralic locative *-nA, with the *n assimilated to the preceding consonant.

- The elative *-stA and the ablative *-ltA similarly continue the original Uralic ablative *-tA.

- The origin of the illative *-sen and the allative *-len is less clear. These have also

- The element *-s- in the first series has parallels across the other more western Uralic languages, sometimes resulting in formally identical case endings (e.g. an elative ending *-stē ← *-s-tA is found in the Samic languages, and *-stə ← *s-tA in the Mordvinic languages), though its original function is unclear.

- The *-l- in the 2nd series likely originates by way of affixation and grammaticalization of the root *ülä- "above, upper" (cf. the prepositions *üllä ← *ül-nä "above", *ültä "from above").

See also

Notes

- ↑ Outside Finland, the term Finnic languages has traditionally been used as a synonym of the extensive group of Finno-Permic languages, including the Baltic Finnic, Permic, Sami languages, and the languages of the Volga Finns.[2][3] At the same time, Finnish scholars have restricted it to the Baltic Finnic languages;[4] the survey volume The Uralic Languages uses the Latinate spelling Fennic to distinguish this Baltic Finnic (Balto-Fennic) use from the broader Western sense of the word.[5] In 2009, the 16th edition of Ethnologue: Languages of the World abandoned the Finno-Permic clade altogether and adopted the nomenclature of Finnish scholars.[6]

Citations

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Finnic". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ "The languages of Europe". Encyclopedia of European peoples, Volume 1. Infobase Publishing. 2006. p. 888.

- ↑ Ruhlen, Merritt (1991). "Uralic-Yukaghir". A Guide to the World's Languages: Classification. Stanford University Press. p. 69. ISBN 0-8047-1894-6.

- 1 2 Laakso 2001, p. 180.

- ↑ Daniel Abondolo, ed. (1998). The Uralic Languages. Routledge Language Family Descriptions. Taylor & Francis.

- ↑ "Language Family Trees, Uralic, Finnic". Ethnologue. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- 1 2 Junttila, Santeri (2010). "Itämerensuomen seuraava etymologinen sanakirja" (PDF). In Saarinen, Sirkka; Siitonen, Kirsti; Vaittinen, Tanja. Sanoista kirjakieliin. Juhlakirja Kaisa Häkkiselle 17. marraskuuta 2010. Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia. 259. ISSN 0355-0230.

- ↑ Finnic Peoples at Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Pajusalu, Karl (2009). "The reforming of the Southern Finnic language area" (pdf). Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne. 258: 95–107. ISSN 0355-0230. Retrieved 2015-03-03.

- 1 2 3 4 The Uralic Languages: Description, History and Foreign Influences By Denis Sinor ISBN 90-04-07741-3

- 1 2 3 Kallio, Petri (2007). "Kantasuomen konsonanttihistoriaa" (PDF). Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne (in Finnish). 253: 229–250. ISSN 0355-0230. Retrieved 2009-05-28.

- ↑ Laakso & 2001 207.

- 1 2 3 4 Viitso 1998, p. 101.

- 1 2 Sammallahti, Pekka (1977), "Suomalaisten esihistorian kysymyksiä" (PDF), Virittäjä: 119–136, retrieved 2015-03-25

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kallio, Petri (2014), "The Diversification of Proto-Finnic", in Frog; Ahola, Joonas; Tolley, Clive, Fibula, Fabula, Fact. The Viking Age in Finland, Studia Fennica Historica, 18, Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, ISBN 978-952-222-603-7

- ↑ Viitso, Tiit-Rein: Finnic Affinity. Congressus Nonus Internationalis Fenno-Ugristarum I: Orationes plenariae & Orationes publicae. (Tartu 2000)

- ↑ Posti, Lauri (1953): From Pre-Finnic to Late Proto-Finnic. In: Finnische-Ugrische Forschungen vol. 31

- ↑ Kallio, Petri (2000): Posti's Superstrate Theory at the Threshold of a New Millennium. In: J. Laakso (ed.), Facing Finnic: Some Challenges to Historical and Contact Linguistics. Castrenianumin toimitteita 59.

References

- Laanest, Arvo (1975), Sissejuhatus läänemeresoome keeltesse (in Estonian), Tallinn

- Laanest, Arvo (1982), Einführung in die ostseefinnischen Sprachen (in German), Hamburg: Buske (German translation of Laanest 1982)

- Kettunen, Lauri (1960), Suomen lähisukukielten luonteenomaiset piirteet, Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia, 119

- Laakso, Johanna (2001), "The Finnic languages", in Dahl, Ö.; Koptjevskaja-Tamm, M., The Circum-Baltic languages. Typology and Contact. Volume I: Past and Present, Amsterdam: John Benjamins

- Laakso, Johanna, ed. (2000), Facing Finnic. Some challenges to historical and contact linguistics, Castrenianumin toimitteita, 59, Helsinki: Helsingin yliopisto

- Setälä, E. N. (1891–1937), Yhteissuomalainen äännehistoria, Helsinki

- Viitso, Tiit-Rein (1998), "Fennic", in Abondolo, Daniel, Uralic languages, Routledge

External links

- Tapani Salminen. Problems in the taxonomy of the Uralic languages in the light of modern comparative studies.

- Lexicon of Early Indo-European Loanwords Preserved in Finnish

- Swadesh list for Finnic languages (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)