Four Days' Battle

| Four Days' Battle | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Anglo–Dutch War | |||||||

The Four Days' Battle, 1–4 June 1666 (Pieter Cornelisz van Soest), c. 1666. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| George Monck | Michiel de Ruyter | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 79 ships | 84 ships | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

17 ships sunk, 6 ships captured,[1] ~1,500 killed, 1,450 wounded, 1,800 captured |

4 ships lost, ~1,500 killed, 1,300 wounded | ||||||

The Four Days' Battle was a naval battle of the Second Anglo–Dutch War. Fought from 1 June to 4 June 1666 in the Julian or Old Style calendar then used in England (11 June to 14 June New Style) off the Flemish and English coast, it remains one of the longest naval engagements in history.

In June 1665 the English had soundly defeated the Dutch in the Battle of Lowestoft, but failed to take advantage of it. The Dutch Spice Fleet, loaded with fabulous riches, managed to return home safely after the Battle of Vågen. The Dutch navy was enormously expanded through the largest building programme in its history. In August 1665 already the English fleet was again challenged, though no large battles resulted. In 1666, the English became anxious to destroy the Dutch navy completely before it could grow too strong and were desperate to end the activity of Dutch raiders as a collapse of English trade threatened.

On learning that the French fleet intended to join the Dutch at Dunkirk, the English decided to prevent this by splitting their fleet. Their main force would try to destroy the Dutch fleet first, while a squadron under Prince Rupert was sent to block the Strait of Dover against the French – who did not appear.

At the start of the battle the English fleet of 56 ships commanded by George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle who also commanded the Red Squadron, was outnumbered by the 84-strong Dutch fleet commanded by Lieutenant-Admiral Michiel de Ruyter. The battle ended with an English flight into a fog bank after both fleets had expended most of their ammunition.

The Dutch inflicted significant damage on the English fleet. The English had gambled that the crews of the many new Dutch ships of the line would not have been fully trained yet but were deceived in their hopes: they lost 23 ships in total (17 sunk and 6 captured), with around 1,500 men killed including two Vice-Admirals, Sir Christopher Myngs and Sir William Berkeley, while about 2000 English were taken prisoner. Dutch losses were four ships destroyed by fire and over 1,550 men killed, including Lieut-Admiral Cornelis Evertsen, Vice-Admiral Abraham van der Hulst and Rear-Admiral Frederik Stachouwer.

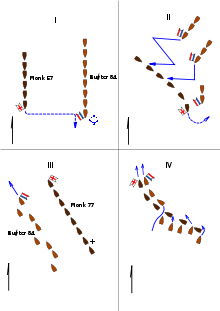

First Day

.jpg)

On the first day Monck, sailing in the van with George Ayscue's white squadron behind him and Thomas Teddiman's blue squadron forming the rear, surprised the Dutch fleet at anchor near Dunkirk. Despite disadvantageous weather conditions Monck decided to attack the Dutch rear under Lieutenant-Admiral Cornelis Tromp hoping to cripple it before the Dutch centre and van could intervene. After sending a message to Rupert to join him if possible, Monck aggressively attacked Tromp who fled over the Flemish shoals. Monck then wore to the northwest, to meet the Dutch centre (under De Ruyter) and van (commanded by Lieutenant-Admiral Cornelis Evertsen the Elder). Tromp again turned, but his ship Liefde collided with Groot Hollandia. Vice-Admiral Sir William Berkeley saw this and closed in with HMS Swiftsure. Immediately Callantsoog and Reiger came to the rescue of their commander, destroying the rigging of the English ship with chain shot; the Reiger then managed to board the Swiftsure. Berkeley challenged the Dutch sea soldiers, shouting: You dogs, you rogues, have you the heart, so press on board! but was fatally wounded in the throat by a musket ball, after which the Swiftsure was captured. In the powder room the constable was found with his throat cut; he had tried to blow up the ship but his own crew killed him first and drenched the powder, claiming afterwards the man had cut his own throat from pure frustration. The damaged HMS Seven Oaks (the former Sevenwolden) was captured by the Beschermer while HMS Loyal George tried to assist the Swiftsure but this only resulted in the capture of both ships. The embalmed body of Berkeley, after being displayed in The Hague, was later returned to England under a truce, accompanied by a letter of the States General praising the Admiral for his courage. HMS Rainbow, one of the two scouts who had first spotted the Dutch fleet, got isolated and fled to neutral Ostend, chased by twelve ships from Tromp's squadron while the other, the Kent, left the battlefield in search of Rupert's squadron.

Both fleets bombarded each other in a line of battle. The Hof van Zeeland and the Duivenvoorde were hit by fire shot and burnt. The Dutch didn't know of the existence of this type of ammunition, consisting of hollow brass balls filled with a flammable substance, so they were greatly surprised. Luckily for them the English had only a small supply because of the high cost of production.

Monck retreated for the night, but the ship of Rear-Admiral Harman, HMS Henry, drifted to the Dutch lines and was set aflame by two fireships. The parson asked Harman what could save them; when the latter sarcastically replied that the good parson could always jump overboard, to his horror the panicked clergyman at once followed his advice together with a third of the crew. All drowned. Harman made an end to the panic by threatening with a drawn sword to run through anyone showing the slightest inclination to abandon ship. Evertsen now closed in and inquired whether Harman would perhaps like to surrender; it came as no surprise to him the renowned fighter respectfully declined, yelling "I'm not up to it yet!". Despite repeated Dutch attacks and the loss of two masts, one in its fall crushing Harman's leg, the fire was put out and the Henry escaped, with its last shot shooting Evertsen in two.

Second Day

On the morning of the second day Monck decided to destroy the Dutch by a direct attack and sailed to them from the southwest; but De Ruyter in the De Zeven Provinciën crossed his line sailing to the southeast, heavily damaging the English fleet and gaining the weather gauge. HMS Anne, HMS Bristol and HMS Baltimore had to return to the Thames. After a calm used for repairs he turned to attack the English from the south with the red flag raised, the sign for an all-out attack, but just when he approached the enemy line he noticed to his dismay that part of the rear squadron under Tromp had got separated and now was positioned to the other side of the English line who had surrounded Tromp and were giving him his belly full. Often this is explained by assuming Tromp had not followed orders, but although he is indeed infamous for his usual insubordination, this time he simply had not seen the sign flags and the look-out of the centre mistakenly reported a confirmation sign. De Ruyter took in the red flag and broke through the enemy line with Vice Admiral Johan de Liefde, while the rest of the Dutch fleet under Aert van Nes headed south. He secured all of Tromp's ships except the burnt Liefde and the sinking Spieghel on which Vice-Admiral Abraham van der Hulst had just been killed by a musket shot in the breast and returned to join van Nes and the main force by again breaking through, noticing with satisfaction the second time the English ships quickly gave way.

Tromp, switching to his fourth ship already, then visited De Ruyter to thank him for the rescue. Both men were in a dark mood. Rear-Admiral Frederick Stachouwer had also been killed. The previous day the damaged Hollandia had been sent home together with the Gelderland, Delft, Reiger, Asperen and Beschermer to guard the three captured English vessels; now also the damaged Pacificatie, Vrijheid, Provincie Utrecht and Calantsoog had to return and only a handful of the rear squadron remained. Besides, the enemy had again gained the weather gauge, the dangers of which became immediately clear as George Ayscue, seeing the two Admirals together in a vulnerable position, tried to isolate them; with great difficulty they managed to return to their main force.

Both fleets now passed three times in opposite tack; on the second pass De Zeven Provinciën got damaged and De Ruyter retreated from the fight to repair his ship. Later some historians would accuse him of cowardice, but he had strict detailed written orders from the States General to act exactly so, to prevent a repeat of the events of the Battle of Lowestoft when the loss of the supreme commander had wrecked the Dutch command structure. Lieutenant-Admiral Aert van Nes led the third pass.

As the Dutch were in a leeward position their guns had a superior range and some English ships now took dreadful damage. HMS Loyal Subject turned for the home port and had to be written off on arrival. HMS Black Eagle (the former Groningen) raised the distress flag but simply disintegrated before any ships could assist.

Then, at three in the afternoon, a Dutch flotilla of twelve ships appeared on the horizon. Monck was shocked, not because the event was totally unexpected but because his worst fear seemed to come true. The English had learned from their excellent intelligence network that the Dutch planned to keep a strong fourth squadron behind as a tactical reserve. Surely these new ships must be the avantguard of a fresh force. Monck ordered to check for the number of operational English ships. When only 29 ships reported to have any fight left in them, and Rupert was still nowhere to be seen, he decided to withdraw. In fact De Ruyter had just before the battle been convinced by the other admirals to use only three squadrons. Monck had never noticed that the Rainbow had disappeared - indeed he couldn't understand where Berkeley had gone either. The dozen ships were those of Tromp's squadron giving chase and now rejoining the fight after the intended prey had escaped to Ostend. The entire English fleet tacked to the southwest at four. The straggling St Paul (the former Sint Paulus) was captured in the evening.

Third Day

_-_De_verovering_van_het_Engelse_admiraalschip_de_'Royal_Prince'.jpg)

On the third day the English continued to retreat to the west. The Dutch advanced on a broad front, Van Nes still in command, both to catch any more stragglers and to avoid the enormous 32-pounder stern cannons of the big ships. In the evening Rupert, having already on the first day been ordered to join Monck, at last appeared with twenty ships. He had been unable to reach Monck earlier because he had sailed as far as Wight in search of the imaginary French fleet. Monck ordered his fleet to set a straight course for the green squadron despite warnings that this would take them over the infamous Galloper Shoal at low tide. HMS Royal Charles and HMS Royal Katherine indeed were grounded but managed to get free in time, HMS Prince Royal got stuck however. Vice-Admiral George Ayscue, commander of the white squadron, pleaded with his men to stay calm until flood would lift the ship; but when two fire ships approached the crew panicked. A certain Lambeth struck the flag and Ayscue had to surrender to Tromp on the Gouda, the first and last time in history an English admiral of so high a rank would be captured at sea. De Ruyter had clear orders to destroy any prize; as the English fleet was still close he couldn't disobey in the matter of such a capital vessel and ordered the Prince burnt. Tromp didn't dare to make any objections because he had already sent home some prizes against orders; but later he would freely express his discontent, in 1681 still trying to get compensation from the admiralty of Amsterdam for this perceived wrong.

Van Nes now tried to prevent both English fleets from joining. But when they both sailed behind the back of his blocking squadron, De Ruyter took over operational command and ordered to wait. This way he regained the weather gauge.

Fourth Day

Early next morning five more ships (the Convertine, Sancta Maria, Centurion, Kent and Hampshire) and another fireship (Happy Entrance), joined the English fleet; as against these, six of the most damaged ships were sent home for repair. Thus enforced with 23 'fresh' ships and so numbering in between 60 and 65 men-of-war and 6 fireships, the English attacked in line on the fourth day with Sir Christopher Myngs now in charge of the van, Rupert of the center, and Monk of the rear squadron. But the Dutch, now to the southwest and reduced to 68 ships (and some 6 or 7 fireships), had the weather gauge and also attacked aggressively.

De Ruyter had tried to impress on his flag officers that the fight of that day would be decisive for the entire war. The English attack, vulnerable from a leeward position, faltered. De Ruyter had planned to disrupt the English line by breaking it in three places, cutting off parts of the English fleet before dealing with the rest. Vice admiral Johan de Liefde on the Ridderschap and Myngs on the Victory began a close quarters duel; two musket balls hit Myngs, fatally wounding him; he died on his return to London. The English regrouped trying to break free to the south by executing four passes in opposite tack, but Tromp and Van Nes surrounded them. Monck then wore to the north. Tromp's squadron was routed, the Landman burnt by a fireship. Van Nes was forced to withdraw. De Ruyter, more anxious than at any other moment in the battle and fearing the fight lost, raised the red flag and sailed past Rupert to attack Monck from behind. When Rupert tried to do the same to him, three shots in quick succession dismasted his HMS Royal James and the entire squadron of the green withdrew from the battle to the south, protecting and towing the flagship. Nothing now prevented De Ruyter from attacking Monck as the English main force was routed, many of the English ships were short on powder after three days of fighting. The Dutch boarded and captured four stragglers: Wassenaar captured HMS Clove Tree (the former VOC-ship Nagelboom), and the Frisian Rear-Admiral Hendrik Brunsvelt captured HMS Convertine, the entangled HMS Essex and HMS Black Bull; Black Bull later sank.

De Ruyter seeing the English fleet escape in a dense fog decided to break off the pursuit. His own fleet was heavily damaged too; his logbook only speaks of a fear for the English shoals. The deeply religious De Ruyter interpreted the sudden unseasonal fog bank as a sign from God, "that He merely wanted the enemy humbled for his pride but preserved from utter destruction".

Results

The biggest sea battle of the Second Anglo-Dutch War and in the age of sail was a Dutch victory. However, the outcome is sometimes described as inconclusive, because both sides initially claimed victory. Immediately after the battle the English captains of Rupert's squadron, not having seen the final outcome, claimed De Ruyter had retreated first, then normally seen as an acknowledgement of the superiority of the enemy fleet. Though the Dutch fleet was eventually forced to end the pursuit, they had managed to cripple the English fleet, and lost but four smaller ships themselves, for the Spieghel refused to sink and was repaired. The contemporaneous Dutch view on this matter is expressed in a famous epigram by the poet Constantijn Huygens:

- Two fight — and for their lives

- The one that caused the row

- is beaten — but survives

- And boasts: "I've won it now!

- As master of the field!"

- And did he win? For sure!

- Face-down he couldn't yield:

- His victory was pure

- The other took his hat,

- his rapier and his gold

- And left him lying flat,

- The glorious field to hold

- So master he has been:

- Our Neighbours are the same:

- If thus they like to win,

- we wish them lasting fame

Around 1,800 English sailors were taken prisoner and transported to Holland. Many subsequently took service in the Dutch fleet against England. Those that refused to do so remained in Dutch prisons for the following two years.[2]

Two months later the recuperated English fleet challenged the Dutch fleet again, now much more successfully at North Foreland in the St. James's Day Battle. This proved to be a partial victory as the Dutch fleet wasn't destroyed. The enormous costs of repair after both battles depleted the English treasury, so the Four Days' Battle is usually seen as both a tactical and important strategic victory for the Dutch.

References

- ↑ C. M. Davies, The History of Holland (London, 1851), III.25; Barnouw, op. cit., 113: "The British fleets, split by the threat of French naval action (Louis XIV was the nominal ally of the Dutch), were defeated in sustained battle, with the loss of seventeen ships and six prizes."

- ↑ Kemp, Peter (1970). The British Sailor: A Social History of the Lower Deck. JM Dent & Sons. pp. 38–39. ISBN 0460039571.

Further reading

- Fox, Frank L., A Distant Storm: The Four Days' Battle of 1666, Rotherfield, 1996. ISBN 0-948864-29-X.

- Van Foreest, HA, Weber, REJ, De Vierdaagse Zeeslag 11–14 June 1666, Amsterdam, 1984.

Film

The Four Days' Battle is dramatized in the Dutch-English film Admiral (2015), also known as "Michiel de Ruyter" although it is not clear which phase of the battle is shown.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Four Days Battle. |

Coordinates: 51°24′N 2°0′E / 51.400°N 2.000°E