Fred Hargesheimer

| Major Fred Hargesheimer | |

|---|---|

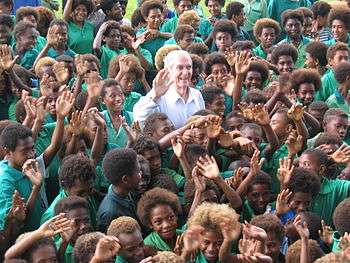

Fred Hargesheimer, 2008 | |

| Born |

May 7, 1916 Rochester, Minnesota |

| Died |

December 23, 2010 (aged 94) Lincoln, Nebraska |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | United States Army Air Corps |

| Years of service | 1941–1945 |

| Rank | Major |

| Unit | 8th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards |

Purple Heart Silver Star Distinguished Flying Cross Air Medal Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal |

Major Fred Hargesheimer (May 7, 1916 – December 23, 2010) was a former pilot of the USAAF who was shot down during World War II over Papua New Guinea in June 1943. He later became a philanthropist who helped out the village that had hidden him from the Japanese.

Early life

Hargesheimer was born and raised in Rochester, Minnesota. He earned a BS in Electrical Engineering from Iowa State College in 1940 before moving to Alpine, New Jersey, to work for FM radio pioneer Edwin H. Armstrong.[1]

World War II

Hargesheimer served with the 8th Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron of the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II. He was flying a Lockheed P-38F-4 on a photo reconnaissance mission on June 5, 1943, over the island of New Britain, Papua New Guinea, when his plane was attacked by a Japanese Ki-45 Nick fighter. Despite his injuries and jammed canopy, he was able to parachute to safety. For the next month he fought to survive in the jungle. He was found by members of the Nakanai tribe after 31 days. They sheltered him for five months in the village of Ea Ea, risking their lives to protect him from being found by Japanese soldiers. He met up with Australian Coastwatchers who moved him inland. On February 5, 1944, Fred, along with other downed airmen, was rescued by the submarine USS Gato. He was awarded the Purple Heart, the Silver Star, the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal, and the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal. After the war, he returned to his hometown of Rochester, Minnesota, where he raised a family of his own.

Philanthropy

Hargesheimer corresponded with a missionary to learn how the tribe that kept him safe had fared and in 1960 returned to the island. He was told that they needed a school. He came home and raised $15,000 over three years, "most of it $5 and $10 gifts," and then returned with son Richard in 1963 to contract for the construction of the school.[2] The simple four-room schoolhouse became known as the Airmen's Memorial School * . Hargesheimer returned many times for the next 40 years, building a library as well as infrastructure for the village of Ea Ea, now known as Nantabu. From 1970 to 1974 he and his wife, Dorothee, lived there.[2] He was known by the locals as Mastah Preddi, a corruption of Master Freddie. In 2000, he was proclaimed "Suara Auru," or "Chief Warrior" in the native language. Hargesheimer returned in 2006 for his last visit. During the trip, he visited the site where the wreckage of his old P-38 had been recently found. Hargesheimer also attended the opening of a new library at the Noau school.

Contact with his attacker

In 1999, aided by amateur Japanese historians of World War II, he contacted the wife of the man who had shot him down. He had always wondered why the pilot had never taken the time to finish him off when he was parachuting to the ground. By then the man, Mitsugu Hyakutomi of Yamaguchi, Japan, was suffering from Alzheimer's disease. His wife said that her husband had always said that he could never shoot down such defenseless parachuting fliers.[3]

Death

He died in Lincoln, Nebraska, on December 23, 2010.[2]

Bibliography

- Hargesheimer, Fred. The School That Fell From The Sky ISBN 978-1-58909-116-0

References

- ↑ Nelson, Ed. "Fred Hargesheimer and ERA/Univac Story" (PDF). 2007. Vipclubmn. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- 1 2 3 WWII Pilot who Forever Repaid Rescuers Dies at 94, The Associated Press, December 23, 2010

- ↑ Hanley, Charles J. "'Mastah Preddi' fell from the sky, into hearts Islanders heal, hail WW2 pilot; man changes lives, returns to build school". Mar 8 2008. MSNBC via AP. Retrieved 24 December 2010.