Galeazzo Ciano

| Galeazzo Ciano | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

|

In office 9 June 1936 – 6 February 1943 | |

| Duce | Benito Mussolini |

| Preceded by | Benito Mussolini |

| Succeeded by | Benito Mussolini |

| Minister of Press and Propaganda | |

|

In office 23 June 1935 – 5 September 1935 | |

| Duce | Benito Mussolini |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Dino Alfieri |

| Undersecretary for Press and Propaganda | |

|

In office 6 September 1934 – 26 June 1935 | |

| Duce | Benito Mussolini |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Head of the Government Press Office | |

|

In office August 1933 – 4 September 1934 | |

| Duce | Benito Mussolini |

| Preceded by | Gaetano Polverelli |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Gian Galeazzo Ciano 18 March 1903 Livorno, Tuscany, Italy |

| Died |

11 January 1944 (aged 40) Verona, Italian Social Republic |

| Cause of death | Executed by firing squad |

| Political party | National Fascist Party (PNF) |

| Spouse(s) | Edda Mussolini (m. 1930) |

| Children |

Fabrizio Raimonda Marzio |

| Parents |

Costanzo Ciano (father) Carolina Pini (mother) |

| Profession |

|

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

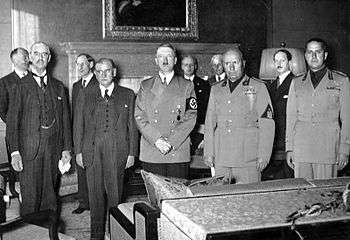

Gian Galeazzo Ciano, 2nd Count of Cortellazzo and Buccari (Italian pronunciation: [ɡale'attso ˈtʃaːno]; 18 March 1903 – 11 January 1944) was Foreign Minister of Fascist Italy from 1936 until 1943 and Benito Mussolini's son-in-law. On 11 January 1944, Count Ciano was shot by firing squad at the behest of his father-in-law, Mussolini, under pressure from Nazi Germany.[1] Ciano wrote and left behind a diary[2] that has been used as a source by several historians, including William Shirer in his The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich and in the 4-hour HBO documentary-drama Mussolini and I.

Early life

Gian Galeazzo Ciano was born in Livorno, Italy, in 1903. He was the son of Costanzo Ciano and his wife Carolina Pini; his father was an Admiral and World War I hero in the Royal Italian Navy (for which service he was given the aristocratic title of Count by Victor Emmanuel III). He was a founding member of the National Fascist Party and re-organizer of the Italian merchant navy in the 1920s. The elder Ciano, nicknamed Ganascia ("The Jaw"), was not above extracting private profit from his public office. He would use his influence to depress the stock of a company, after which he would buy a controlling interest, then increase his wealth after its value rebounded. Among other holdings, he owned a newspaper, farmland in Tuscany and other properties worth huge sums of money. As a result, his son Galeazzo was accustomed to living a high-profile and glamorous life, which he maintained almost until the end of his life. Father and son both took part in Mussolini's 1922 March on Rome.

After studying Philosophy of Law at the University of Rome, the younger Ciano worked briefly as a journalist before choosing a diplomatic career; soon, he served as an attaché in Rio de Janeiro.

On 24 April 1930, when he was 27 years old, he married Benito Mussolini's daughter Edda Mussolini, and they had three children (Fabrizio, Raimonda, and Marzio). Soon after their marriage, Ciano left for Shanghai to serve as Italian consul. On his return to Italy in 1935, he became the minister of press and propaganda in the government of his father-in-law.

Foreign Minister

Ciano volunteered for action in the Italian invasion of Ethiopia (1935–36) as a bomber squadron commander. He received two silver medals of valor and reached the rank of captain. His future opponent Alessandro Pavolini served in the same squadron as a lieutenant. Upon his highly trumpeted return from the war as a "hero" in 1936, he was appointed by Mussolini as replacement Foreign Minister. Ciano began to keep a diary a short time after his appointment and kept it active up to his dismissal as foreign minister in 1943. The following year, he was allegedly involved in planning the murder of the brothers Carlo Rosselli and Nello Rosselli, two exiled anti-fascist activists killed in the French spa town of Bagnoles-de-l'Orne on 9 June 1937. In 1937, prior to the Italian annexation in 1939, Count Gian Galeazzo Ciano was named an Honorary Citizen of Tirana, Albania.[3]

At the time of the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Ciano did not agree with Mussolini's war plans and knew that Italy's armed forces were ill-prepared for a major war. When Mussolini formally declared war on France in 1940, he wrote in his diary, "I am sad, very sad. The adventure begins. May God help Italy!" After 1939, Ciano became increasingly disenchanted with Nazi Germany and the course of World War II, although when the Italian regime embarked on an ill-advised "parallel war" alongside Germany, he went along, despite the terribly-executed Italian invasion of Greece and its subsequent setbacks. Prior to the German campaign in France in 1940, Count Ciano leaked a warning of imminent invasion to neutral Belgium.

In late 1942 and early 1943, following the Axis defeat in North Africa, other major setbacks on the Eastern Front, and with an Anglo-American assault on Sicily looming, Ciano turned against the doomed war and actively pushed for Italy's exit from the conflict. He was silenced by being removed from his post as foreign minister. The rest of the cabinet was removed as well on 5 February 1943. He was offered the post of ambassador to the Holy See, and presented his credentials to Pope Pius XII on 1 March.[4] In this role he remained in Rome, watched closely by Mussolini. The regime's position had become even more unstable by the coming summer, however, and court circles were already probing the Allied commands for some sort of agreement.

On the afternoon of 24 July 1943, Mussolini summoned the Fascist Grand Council to its first meeting since 1939, prompted by the Allied invasion of Sicily. At that meeting, Mussolini announced that the Germans were thinking of evacuating the south. This led Count Dino Grandi to launch a blistering attack on his longtime comrade. Grandi put on the table a resolution asking King Victor Emmanuel III to resume his full constitutional powers — in effect, a vote leading to Mussolini's ousting from leadership. The motion won by an unexpectedly large margin, 19-8, with Ciano voting in favor. Mussolini's replacement was Pietro Badoglio, an Italian general in both World Wars.

Mussolini did not think that the vote had any real value, and showed up at work the next morning like any other day. That afternoon, the king summoned him to Villa Savoia and dismissed him from office. Upon leaving the villa, Mussolini was arrested. For the next two months he was moved from place to place to hide him and prevent his rescue by the Germans. Ultimately, Mussolini was sent to Gran Sasso, a mountain resort in Abruzzo. He was kept in complete isolation until rescued by the Germans on 12 September 1943. Mussolini then set up a puppet government in the area of northern Italy still under German occupation called the Repubblica Sociale Italiana (R.S.I.), the Italian Social Republic.

Death

Ciano was dismissed from his post by the new government of Italy put in place after his father-in-law was overthrown. Ciano, Edda and their three children fled to Germany on 28 August 1943, in fear of being arrested by the new Italian government, but the Germans returned him to Mussolini and the R.S.I. He was then formally arrested on charges of treason. Under German and fascist pressure, Mussolini had Ciano imprisoned before he was tried and found guilty. After the Verona trial and sentence, on 11 January 1944, Ciano was executed by a firing squad along with 4 others (Emilio De Bono, Luciano Gottardi, Giovanni Marinelli and Carlo Pareschi) who had voted for Mussolini's ousting. As a further humiliation, the executed Italians were tied to chairs and shot in the back. Ciano's last words were "Long live Italy!"[5]

Ciano is remembered for his famous Diaries 1937–1943, a daily record of his meetings with Mussolini, Hitler, Ribbentrop, foreign ambassadors and other political figures, which later proved embarrassing to the Nazi leadership and the fascist diehards. Edda tried to barter his papers to the Germans in return for his life; Gestapo agents helped her confidant Emilio Pucci rescue some of them from Rome. Pucci was then a lieutenant in the Italian Air Force, but would find fame after the war as a fashion designer. When Hitler vetoed the plan, she hid the bulk of the papers at a clinic in Ramiola, near Medesano and on 9 January 1944, Pucci helped Edda escape to Switzerland with five diaries covering the war years.[6] The diary was first published in English in London in 1946, edited by Malcolm Muggeridge, for 1939 to 1943. The complete English version was published in 2002.

Children

Gian Galeazzo and Edda Ciano had three offspring:

- Oldest child, Fabrizio Ciano, 3º Conte di Cortellazzo e Buccari (Shanghai, 1 October 1931 – San José, Costa Rica, 8 April 2008), married to Beatriz Uzcategui Jahn, without issue. Wrote a personal memoir entitled Quando il nonno fece fucilare papà ("When Grandpa had Daddy Shot").

- Middle child, Raimonda Ciano (Rome, 12 December 1933 - Rome, 24 May 1998), married to Nobile Alessandro Giunta (1929 -), son of Nobile Francesco Giunta (Piero, 1887–1971) and wife (m. Rome, 1924) Zenaida del Gallo Marchesa di Roccagiovine (Rome, 1902 – São Paulo, Brazil, 1988)

- Youngest child, Marzio Ciano, (Rome, 18 December 1937 – 11 April 1974), married to Gloria Lucchesi

In popular culture

- A number of films have depicted Ciano's life, including The Verona Trial (1962) by Carlo Lizzani, where he is played by Frank Wolff and Mussolini and I (1985) in which he was played by Anthony Hopkins.

- Raúl Juliá played Ciano in the 1985's television mini-series, Mussolini: The Untold Story.

- In Serbia there is proverb : "Living like count Ciano" - describing a flamboyant and luxurious life (Živi ko grof Ćano/Живи ко гроф Ћано)

- Ciano's diaries were published in 1946 and were used by the prosecution against Hitler's Foreign Minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, during the post war Nuremberg Trials.

References

Notes

- ↑ Moseley, Ray (2004). Mussolini : the last 600 days of il Duce (1. ed.). Dallas: Taylor Trade Publ. p. 79. ISBN 1589790952.

- ↑ Ciano, Galeazzo (2002). Diary, 1937-1943 (1st complete and unabridged English ed.). New York: Enigma Books. ISBN 1929631022.

- ↑ Municipality of Tirana website, tirana.gov.al; accessed 5 January 2016.

- ↑ Pius XII speech at the presentation of credentials (in Italian)

- ↑ "Mussolini's Daughter’s Affair with Communist Revealed in Love Letters". The Telegraph, 17 April 2009; retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ↑ McGaw Smyth, Howard (1969). "The Ciano Papers: Rose Garden". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

Bibliography

- Galeazzo Ciano, Ciano's Diary, 1939-1943, edited and with an introduction by Malcolm Muggeridge, foreword by Sumner Welles, translated by V. Umberto Coletti-Perucca, London and Toronto: William Heinemann Ltd., (1947).

- Ciano's diplomatic papers: being a record of nearly 200 conversations held during the years 1936–42 with Hitler, Mussolini, Franco; together with important memoranda, letters, telegrams etc. / edited by Malcolm Muggeridge; translated by Stuart Hood, London: Odhams Press, (1948).

- Galeazzo Ciano, Diary 1937–1943, Preface by Renzo De Felice (Professor of History University of Rome) and original introduction by Sumner Welles (U.S. Under Secretary of State 1937–1943), translated by Robert L. Miller (Enigma Books, 2002), ISBN 1-929631-02-2

- The Ciano Diaries 1939–1943: The Complete, Unabridged Diaries of Count Galeazzo Ciano, Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, 1936–1943 (2000) ISBN 1-931313-74-1

- Giordano Bruno Guerri – Un amore fascista. Benito, Edda e Galeazzo. (Mondadori, 2005) ISBN 88-04-53467-2

- Чиано Галеаццо, Дневник фашиста. 1939–1943, (Москва: Издательство "Плацъ", Серия "Первоисточники новейшей истории", 2010, 676 стр.) ISBN 978-5-903514-02-1

- Ray Moseley – Mussolini's Shadow: The Double Life of Count Galeazzo Ciano, (Yale University Press, 1999) ISBN 0-300-07917-6

- R.J.B. Bosworth – Mussolini (Hodder Arnold, 2002) ISBN 0-340-73144-3

- Michael Salter and Lorie Charlesworth – "Ribbentrop and the Ciano Diaries at the Nuremberg Trial" in Journal of International Criminal Justice 2006 4(1):103–127 doi:10.1093/jicj/mqi095

- Fabrizio Ciano – Quando il nonno fece fucilare papà ("When Grandpa had Daddy Shot"). Milano: Mondadori, 1991.

- "Galeazzo Ciano’s Last Reflections before Execution." World War II Today RSS. Accessed 25 March 2015.

- "Galeazzo Ciano - a Summary - History in an Hour." History in an Hour. 10 January 2014. Accessed 25 March 2015.

- "Gian Galeazzo Ciano - Comando Supremo." Comando Supremo. 14 February 2010. Accessed 25 March 2015.

- "The Ciano Papers: Rose Garden." Central Intelligence Agency. 4 August 2011. Accessed 25 March 2015.

External links

Quotations related to Galeazzo Ciano at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Galeazzo Ciano at Wikiquote Media related to Galeazzo Ciano at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Galeazzo Ciano at Wikimedia Commons

| Italian nobility | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Costanzo Ciano |

Count of Cortellazzo and Buccari 1939–1944 |

Succeeded by Fabrizio Ciano |

| Government offices | ||

| Preceded by Gaetano Polverelli |

Head of the Government Press Office 1933–1934 |

Succeeded by None (Office abolished) Himself as Undersecretary for Press and Propaganda |

| Preceded by None (Office established) |

Undersecretary for Press and Propaganda 1934–1935 |

Succeeded by None (Office abolished) Himself as Minister for Press and Propaganda |

| Preceded by None (Office established) |

Minister of Press and Propaganda 1935 |

Succeeded by Dino Alfieri |

| Preceded by Benito Mussolini |

Minister of Foreign Affairs 1936–1943 |

Succeeded by Benito Mussolini |