Gangs of New York

| Gangs of New York | |

|---|---|

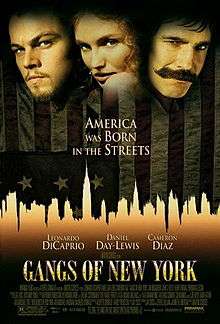

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Martin Scorsese |

| Produced by | |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by | Jay Cocks |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Howard Shore |

| Cinematography | Michael Ballhaus |

| Edited by | Thelma Schoonmaker |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Miramax Films |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 168 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $97 million |

| Box office | $193.7 million |

Gangs of New York is a 2002 American epic period drama film set in the mid-19th century in the Five Points district of New York City. It was directed by Martin Scorsese and written by Jay Cocks, Kenneth Lonergan, and Steven Zaillian. The film was inspired by Herbert Asbury's 1927 nonfiction book, The Gangs of New York. It was made in Cinecittà, Rome, distributed by Miramax Films and nominated for numerous awards, including the Academy Award for Best Picture.

The film begins in 1846 and quickly jumps to 1862. Two issues of the era in New York were Irish immigration to the city and the Civil War. The story follows gang leader Bill "The Butcher" Cutting (Daniel Day-Lewis) in his roles as crime boss and political kingmaker under the helm of "Boss" Tweed (Jim Broadbent). The film culminates in a violent confrontation between Cutting and his mob with the protagonist Amsterdam Vallon (Leonardo DiCaprio) and his immigrant allies, which coincides with the New York Draft Riots of 1863.

Plot

In 1846, in Lower Manhattan's "Five Points" district, a territorial war raging for years, between the "Natives" and recently arrived Irish, Catholic immigrants, is about to come to a head in Paradise Square. The Natives are led by William "Bill the Butcher" Cutting (Daniel Day-Lewis), an American Protestant nativist, with an open hatred of recent immigrants. The leader of the immigrant Irish, the "Dead Rabbits", is Priest Vallon (Liam Neeson), who has a young son, Amsterdam (played as a child by Cian McCormack). Cutting and Vallon meet with their respective gangs in a horrific and bloody battle, concluding when Bill kills Priest Vallon, which Amsterdam witnesses. Cutting declares the Dead Rabbits outlawed and orders Vallon's body be buried with honor. Amsterdam seizes the knife that kills his father, races off and buries it. He is found and taken to the orphanage at Hellgate.

Sixteen years later, Amsterdam returns to New York as a grown man (Leonardo DiCaprio) in the second year of the Civil War. It is September 1862, days after the Battle of Antietam and the announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation. Arriving in Five Points, he reunites with an old friend, Johnny Sirocco (Henry Thomas). Johnny, now a member of a clan of pickpockets and thieves, introduces Amsterdam to Bill the Butcher, for whom the group steals. Amsterdam finds many of his father's old loyalists are now under Bill's control, including Happy Jack Mulraney (John C. Reilly), now a corrupt city constable and in Bill's pocket and McGloin (Gary Lewis), now one of Bill's lieutenants. Amsterdam soon works his way into the Butcher's inner circle. Amsterdam learns that each year, on the anniversary of the Five Points battle (February 16), Bill leads the city in saluting the victory over the Dead Rabbits and he makes plans to kill the Butcher during this ceremony, in front of the entire Five Points community, to exact public revenge. Amsterdam meets Jenny Everdeane (Cameron Diaz), a pickpocket and grifter. Amsterdam is attracted to Jenny (as is Johnny) but his interest is dampened when Amsterdam discovers Jenny was once the Butcher's ward and still enjoys Bill's affections. Amsterdam gains Bill's confidence as Bill becomes his mentor. He becomes involved in the semi-criminal empire of William M. Tweed (Jim Broadbent) also known as "Boss" Tweed, a corrupt politician who heads Tammany Hall, the local political machine. Tweed's influence is spread throughout Lower Manhattan from boxing matches to sanitation services and fire control. As Tammany Hall and its opponents fight for control of the city, the political climate is boiling. Immigrants, mostly Irish, are enlisted into the Union Army as they depart the boats.

During a performance of Uncle Tom's Cabin, Amsterdam thwarts an assassination attempt that leaves the Butcher wounded. Amsterdam is tormented by the realization he acted more out of honest devotion to Bill than from his own plan of revenge. Both retire to a brothel, where Jenny nurses Bill. Amsterdam confronts Jenny over Bill and the two have a furious argument which dissolves into passionate lovemaking. Late that night, Amsterdam wakes to find Bill sitting by his bed in a rocking chair, draped in a tattered American flag. Bill speaks of the downfall of civilization and how he has maintained his power over the years through violence and the "spectacle of fearsome acts". He says Priest Vallon was the last enemy he ever fought who was worthy of real respect and the Priest once beat Bill soundly and then let him live in shame rather than kill him. Bill credits the incident with giving him strength of will and character to return and fight for his own authority. Bill implicitly admits he has come to look upon Amsterdam as the son he never had. The evening of the ceremony arrives. Johnny, who is in love with Jenny, reveals Amsterdam's true identity to Bill in a fit of jealousy and tells Bill of his plot to kill him. Bill baits Amsterdam with a knife-throwing act involving Jenny, where he targets her and throws the knife to leave a superficial cut on her throat. As Bill makes the customary toast, Amsterdam throws a knife at Bill, which Bill easily deflects and counters with a knife throw of his own, hitting Amsterdam in the abdomen. Bill then repeatedly beats and head butts him as the crowd cheers him on. The Butcher proclaims he will let Amsterdam live in shame (a fate worse than death) as "[a] freak. Worthy of Barnum's museum of wonders" before burning his cheek with a hot blade.

Jenny and Amsterdam go into hiding; Jenny takes care of Amsterdam and nurses him back to health. She implores him to join her in an escape to the frontier city of San Francisco. The two are visited by Walter "Monk" McGinn (Brendan Gleeson), a barber who worked as a mercenary for Priest Vallon in the Battle of the Five Points. McGinn gives Amsterdam a straight razor that belonged to his father. Amsterdam announces his return by placing a dead rabbit on a fence in Paradise Square. The rabbit finds its way to Bill, who sends Happy Jack to find out who sent the message. Jack tracks down Amsterdam and chases him through the catacombs into the local church where Amsterdam ambushes and strangles him. He hangs his body in Paradise Square for all to see. In retaliation, Bill has Johnny beaten nearly to death and run through with an iron pike, leaving it to Amsterdam to end his suffering. Mcgloin (Gary Lewis), one of Bill's friends, later goes to pray at the Catholic Church. Amsterdam had previously recognized him as a man who had fought for the Dead Rabbits years ago. When Mcgloin, a well-known racist, sees Amsterdam's black friend, Jimmy Spoils (Larry Gilliard Jr.), he objects to the idea of letting a negro in the church. Amsterdam and his friends respond by beating Mcgloin and the Archbishop joins in. The Natives soon march to the Catholic Church as the Irish, along with the Archbishop, stand on the steps in defense. Bill promises to return when they are ready and the incident garners newspaper coverage. Boss Tweed approaches Amsterdam with a plan to defeat Bill and his influence, hoping to cash in on the publicity: Tweed will back the candidacy of Monk McGinn for sheriff in return for the support of the Irish vote. On election day, Bill and Amsterdam force people to vote, some of them several times and the result is Monk winning by more votes than there are voters. Humiliated, Bill confronts Monk who fails to respond to the violent challenge, suggesting they discuss the matter democratically. Whereupon Bill throws a meat cleaver into Monk's back before finishing him off with his own shillelagh. During Monk's subsequent funeral, Amsterdam issues a traditional challenge to fight, which Bill accepts.

The New York Draft Riots break out just as the gangs are preparing to fight. Many people of the city, particularly upper-class citizens and African-Americans, are attacked by those protesting the Enrollment Act of 1863. Union Army soldiers march through the city streets trying to control the rioters. For Bill and Amsterdam, what matters is settling their own scores. As the rival gangs meet in Paradise Square, they are interrupted by cannon fire from Union naval ships in the harbor firing directly into Paradise Square. Many are killed by the cannons, as an enormous cloud of dust and debris covers the area. The destruction is followed by a wave of Union soldiers, who wipe out many of the gang members, including McGloin. Abandoning their gangs, Amsterdam and Bill exchange blows in the haze, then are thrown to the ground by another cannon blast. When the smoke clears, Bill discovers he has been stabbed in the abdomen by a piece of shrapnel. He declares, "Thank God, I die a true American." Amsterdam draws a knife from his boot and stabs Bill who dies with his hand locked in Amsterdam's.

The dead are collected for burial; Bill's body is buried on a hilltop cemetery, in Brooklyn, in view of the Manhattan skyline, adjacent to the grave of Priest Vallon. Jenny and Amsterdam visit, as Amsterdam buries his father's razor. Both decide to leave New York on a ship bound for San Francisco to start a new life together. Amsterdam narrates that New York would be rebuilt as if "we were never here". The scene then shifts over the next hundred years, giving a view as modern New York is built up from the Brooklyn Bridge to the World Trade Center, and the graves of Bill and Priest are gradually forgotten, being overgrown by bushes and weeds.

Cast

|

|

Production

| "The country was up for grabs, and New York was a powder keg. This was the America not the West with its wide open spaces, but of claustrophobia, where everyone was crushed together. On one hand, you had the first great wave of immigration, the Irish, who were Catholic, spoke Gaelic, and owed allegiance to the Vatican. On the other hand, there were the Nativists, who felt that they were the ones who had fought and bled, and died for the nation. They looked at the Irish coming off the boats and said, ‘What are you doing here?’ It was chaos, tribal chaos. Gradually, there was a street by street, block by block, working out of democracy as people learned somehow to live together. If democracy didn't happen in New York, it wasn't going to happen anywhere." |

| — Martin Scorsese on how he saw the history of New York City as the battleground of the modern American democracy[2] |

Filmmaker Martin Scorsese had grown up in Little Italy in the borough of Manhattan in New York City during the 1950s. At the time, he had noticed there were parts of his neighborhood that were much older than the rest, including tombstones from the 1810s in Old St. Patrick's Cathedral, cobblestone streets and small basements located under more recent large buildings; this sparked Scorsese's curiosity about the history of the area: "I gradually realized that the Italian-Americans weren’t the first ones there, that other people had been there before us. As I began to understand this, it fascinated me. I kept wondering, how did New York look? What were the people like? How did they walk, eat, work, dress?"[2]

In 1970, Scorsese came across Herbert Asbury's The Gangs of New York: An Informal History of the Underworld (1928) about the city's nineteenth century criminal underworld and found it to be a revelation. In the portraits of the city's criminals, Scorsese saw the potential for an American epic about the battle for the modern American democracy.[2] At the time, Scorsese was a young director without money or clout; by the end of the decade, with the success of crime films such as Mean Streets (1973), about his old neighborhood, and Taxi Driver (1976), he was a rising star. In 1979, he acquired screen rights to Asbury's book, however it took twenty years to get the production moving forward. Difficulties arose with reproducing the monumental city scape of nineteenth century New York with the style and detail Scorsese wanted; almost nothing in New York City looked as it did in that time, and filming elsewhere was not an option. Eventually, in 1999, Scorsese was able to find a partnership with Harvey Weinstein, noted producer and co-chairman of Miramax Films.[2]

In order to create the sets that Scorsese envisioned, the production was filmed at the large Cinecittà Studio in Rome, Italy. Production designer Dante Ferretti recreated over a mile of mid-nineteenth century New York buildings, consisting of a five-block area of Lower Manhattan, including the Five Points slum, a section of the East River waterfront including two full-sized sailing ships, a thirty-building stretch of lower Broadway, a patrician mansion, and replicas of Tammany Hall, a church, a saloon, a Chinese theater, and a gambling casino.[2] For the Five Points, Ferretti recreated George Catlin's painting of the area.[2]

Particular attention was also paid to the speech of characters, as loyalties were often revealed by their accents. The film's voice coach, Tim Monich, resisted using a generic Irish brogue and instead focused on distinctive dialects of Ireland and Great Britain. As DiCaprio's character was born in Ireland but raised in the United States, his accent was designed to be a blend of accents typical of the half-Americanized. To develop the unique, lost accents of the Yankee "Nativists" such as Daniel Day-Lewis's character, Monich studied old poems, ballads, newspaper articles (which sometimes imitated spoken dialect as a form of humor) and the Rogue's Lexicon, a book of underworld idioms compiled by New York’s police commissioner, so that his men would be able to tell what criminals were talking about. An important piece was an 1892 wax cylinder recording of Walt Whitman reciting four lines of a poem in which he pronounced the word "world" as "woild", and the "a" of "an" nasal and flat, like "ayan". Monich concluded that native nineteenth century New Yorkers probably sounded something like the proverbial Brooklyn cabbie of the mid-twentieth.[2]

Due to the strong personalities and clashing visions of director and producer, the three year production became a story in and of itself.[2][3][4][5] Scorsese strongly defended his artistic vision on issues of taste and length while Weinstein fought for a streamlined, more commercial version. During the delays, noted actors such as Robert De Niro and Willem Dafoe had to leave the production due to conflicts with their other productions. Costs overshot the original budget by 25 percent, bringing the total cost over $100 million.[3] The increased budget made the film vital to Miramax Films' short term success.[4][6]

After post-production was nearly completed in 2001, the film was delayed for over a year. The official justification was, after the September 11, 2001 attacks certain elements of the picture may have made audiences uncomfortable; the film's closing shot is a view of modern-day New York City, complete with the World Trade Center's towers, despite their having been leveled by the attacks over a year before the film's release.[7] However this explanation was refuted in Scorsese's own contemporary statements, where he noted that the production was still filming pick-ups even into October 2002.[4][8]

Weinstein kept demanding cuts to the film's length, and some of those cuts were eventually made. In December 2001, Jeffrey Wells reviewed a purported workprint of the film as it existed in the fall of 2001. Wells reported the work print lacked narration, was about 20 minutes longer, and although it was "different than the [theatrical] version ... scene after scene after scene play[s] exactly the same in both." Despite the similarities, Wells found the work print to be richer and more satisfying than the theatrical version. While Scorsese has stated the theatrical version is his final cut, he reportedly "passed along [the] three-hour-plus [work print] version of Gangs on tape [to friends] and confided, 'Putting aside my contractual obligation to deliver a shorter, two-hour-and-forty-minute version to Miramax, this is the version I'm happiest with,' or words to that effect."[7]

In an interview with Roger Ebert, Scorsese clarified the real issues in the cutting of the film. Ebert notes,

- "His discussions with Weinstein, he said, were always about finding the length where the picture worked. When that got to the press, it was translated into fights. The movie is currently 168 minutes long, he said, and that is the right length, and that's why there won't be any director's cut — because this is the director's cut."[9]

Soundtrack

Robbie Robertson, supervised the soundtrack's collection of eclectic pop, folk, and neo-classical tracks.

Historical accuracy

Scorsese received both praise and criticism for historical depictions in the film. In a PBS interview for the History News Network, George Washington University professor Tyler Anbinder discussed the historical aspects of the film.[10] See also Vincent DiGirolamo's "Such, Such Were the B'hoys," Radical History Review Vol. 90 (Fall 2004), pp. 123–41.

Asbury's book described the Bowery Boys, Plug Uglies, True Blue Americans, Shirt Tails, and Dead Rabbits, who were named after their battle standard, a dead rabbit on a pike.[2] The book also described William Poole, the inspiration for William "Bill the Butcher" Cutting, a member of the Bowery Boys, a bare-knuckle boxer, and a leader of the Know Nothing political movement. Poole did not come from the Five Points and was assassinated nearly a decade before the Draft Riots. Both the fictional Bill and the real one had butcher shops, but Poole is not known to have killed anyone.[11][12] The book also described other famous gangsters from the era such as Red Rocks Farrell, Slobbery Jim and Hell-Cat Maggie, who filed her front teeth to points and wore artificial brass fingernails.[2]

Anbinder said that Scorsese's recreation of the visual environment of mid-19th century New York City and the Five Points "couldn't have been much better".[10] All sets were built completely on the exterior stages of Cinecittà Studios in Rome.[13] By 1860, New York City had 200,000 Irish,[14] in a population of 800,000.[15] The riot which opens the film, though fictional, was "reasonably true to history" for fights of this type, except for the amount of carnage depicted in the gang fights and city riots.[10]

According to Paul S. Boyer, "The period from the 1830s to the 1850s was a time of almost continuous disorder and turbulence among the urban poor. The decade from 1834–1844 saw more than 200 major gang wars in New York City alone, and in other cities the pattern was similar."[16] As early as 1839, Mayor Philip Hone said: "This city is infested by gangs of hardened wretches" who "patrol the streets making night hideous and insulting all who are not strong enough to defend themselves."[17] The large gang fight depicted in the film as occurring in 1846 is fictional, though there was one between the Bowery Boys and Dead Rabbits in the Five Points on July 4, 1857, which is not mentioned in the film.[18] DiGirolamo concludes that "'Gangs of New York' becomes a historical epic with no change over time. The effect is to freeze ethno-cultural rivalries over the course of three decades and portray them as irrational ancestral hatreds unaltered by demographic shifts, economic cycles and political realignments."

In the film, the Draft Riots are depicted mostly as acts of destruction but there was a lot of violence that took place during that week of July 1863. The violence resulted in more than one hundred deaths, most of which were African Americans. They were especially targeted by the Irish gangs, in part because they were afraid of the job competition that more freed slaves would cause in the city.[19]

The film references the infamous Tweed Courthouse, as "Boss" Tweed refers to plans for the structure as being "modest" and "economical".

In the film, Chinese Americans were common enough in the city to have their own community and public venues. Significant Chinese migration to New York City did not begin until 1869 (although Chinese people migrated to America as early as the 1840s), the time when the transcontinental railroad was completed. The Chinese theater on Pell St. was not finished until the 1890s.[20] The Old Brewery, the overcrowded tenement shown in the movie in both 1846 and 1862–63, was actually demolished in 1852.[21]

Release

The original target release date was December 21, 2001, in time for the 2001 Academy Awards but the production overshot that goal as Scorsese was still filming.[4][8] A twenty-minute clip, billed as an "extended preview", debuted at the 2002 Cannes Film Festival and was shown at a star-studded event at the Palais des Festivals et des Congrès with Scorsese, DiCaprio, Diaz and Weinstein in attendance.[8]

Harvey Weinstein then wanted the film to open on December 25, 2002, but a potential conflict with another film starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Catch Me If You Can produced by DreamWorks, caused him to move the opening day to an earlier position. After negotiations between several parties, including the interests of DiCaprio, Weinstein and DreamWorks' Jeffrey Katzenberg, the decision was made on economic grounds: DiCaprio did not want to face a conflict of promoting two movies opening against each other; Katzenberg was able to convince Weinstein that the violence and adult material in Gangs of New York would not necessarily attract families on Christmas Day. Of main concern to all involved was attempting to maximize the film's opening day, an important part of film industry economics.[4]

After three years in production, the film was released on December 20, 2002; a year after its original planned release date.[8]

While the film has been released on DVD and Blu-ray, there are no plans to revisit the theatrical cut or prepare a "director's cut" for home video release. "Marty doesn't believe in that," editor Thelma Schoonmaker stated. "He believes in showing only the finished film."[7]

Reception

Box office

The film made $77,812,000 in Canada and the United States. It also took $23,763,699 in Japan and $16,358,580 in the United Kingdom. Worldwide the film grossed a total of $193,772,504.[22]

Critical reception

Reviews of the eventual release in 2002 were generally positive — the review aggregating website Rotten Tomatoes reporting 75% of the 202 reviews that they tallied were favorable. The RT Critical Consensus reads, "Though flawed, the sprawling, messy Gangs of New York is redeemed by impressive production design and Day-Lewis's electrifying performance."[23]

The review aggregate website Metacritic awarded Gangs of New York a Metascore of 72, indicating generally favorable reviews.[24]

Roger Ebert praised the film but believed it fell short of Scorsese's best work, while his At the Movies co-star Richard Roeper called it a "masterpiece" and declared it a leading contender for Best Picture.[25] Paul Clinton of CNN called the film "a grand American epic".[26] In Variety, Todd McCarthy wrote that the film "falls somewhat short of great film status, but is still a richly impressive and densely realized work that bracingly opens the eye and mind to untaught aspects of American history." McCarthy singled out the meticulous attention to historical detail and production design for particular praise.[27]

Some critics, however, were disappointed with the film, complaining that it fell well short of the hype surrounding it, that it tried to tackle too many themes without saying anything unique about them, and that the overall story was weak.[28]

Awards

- Wins

- BAFTAs: Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis)[29]

- Broadcast Film Critics Association Awards: Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis)[30]

- Chicago Film Critics Association Awards: Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis)[31]

- Florida Film Critics Circle Awards: Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis), Best Director (Martin Scorsese)[32]

- Golden Globes: Best Director (Martin Scorsese), Best Original Song (U2 for "The Hands That Built America")[33]

- Kansas City Film Critics Circle Awards: Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis)[34]

- Las Vegas Film Critics Society Awards: Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis), Best Original Song (U2 for The Hands That Built America)[35]

- Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards: Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis), Best Art Direction (Dante Ferretti)[36]

- New York Film Critics Circle Awards: Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis)[37]

- Online Film Critics Society Awards: Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis)[38]

- San Diego Film Critics Society Awards: Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis)[39]

- Satellite Awards: Best Art Direction (Dante Ferretti), Best Film Editing (Thelma Schoonmaker), Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis)[40]

- Screen Actors Guild Awards: Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis)[41]

- Southeastern Film Critics Association Awards: Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis), Best Director (Martin Scorsese)[42]

- Vancouver Film Critics Circle: Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis)[43]

- Nominations

- Academy Awards: Best Picture, Best Director (Martin Scorsese), Best Art Direction (Dante Ferretti), Best Original Song (U2 for "The Hands That Built America"), Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis), Best Cinematography (Michael Ballhaus), Best Costume Design (Sandy Powell), Best Editing (Thelma Schoonmaker), Best Sound (Tom Fleischman), (Eugene Gearty), (Ivan Sharrock), Best Original Screenplay (Jay Cocks), (Steven Zaillian), (Kenneth Lonergan)[44]

- BAFTAs: Anthony Asquith Award for Film Music (Howard Shore), Best Visual Effects (R. Bruce Steinheimer), (Michael Owens), (Edward Hirsh), (Jon Alexander), Best Cinematography (Michael Ballhaus), Best Costume Design (Sandy Powell), Best Film Editing (Thelma Schoonmaker), Best Picture, Best Makeup/Hair (Manlio Rocchetti), (Aldo Signoretti), Best Art Direction (Dante Ferretti), Best Original Screenplay (Jay Cocks), (Steven Zaillian), (Kenneth Lonergan), Best Sound, David Lean Award for Direction (Martin Scorsese)[29]

- Broadcast Film Critics Association Awards: Best Director (Martin Scorsese), Best Picture[45]

- Chicago Film Critics Association Awards: Best Director (Martin Scorsese), Best Cinematography (Michael Ballhaus)[46]

- Directors Guild of America: Best Director (Martin Scorsese)[47]

- Empire Awards: Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis)[48]

- Golden Globes: Best Motion Picture - Drama, Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis), Best Supporting Actress (Cameron Diaz)[49]

- Online Film Critics Society Awards: Best Art Direction (Dante Ferretti), Best Cinematography (Michael Ballhaus), Best Costume Design (Sandy Powell), Best Director (Martin Scorsese), Best Sound, Best Ensemble[50]

- Phoenix Film Critics Society Awards: Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis), Best Costume Design (Sandy Powell), Best Art Direction (Dante Ferretti), Best Makeup (Manlio Rocchetti), (Aldo Signoretti)[51]

- Satellite Awards: Best Cinematography (Michael Ballhaus), Best Costume Design (Sandy Powell), Best Sound, Best Visual Effects[40]

- Writers Guild of America: Best Original Screenplay (Jay Cocks), (Steven Zaillian), (Kenneth Lonergan)[52]

Honors

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2004: AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

- "The Hands That Built America" – nominated[53]

See also

- Gangs of New York: Music from the Miramax Motion Picture

- Irish Americans in New York City

- Irish Brigade (US)

- List of identities in The Gangs of New York (book)

References

- ↑ "Gangs of New York (18)". British Board of Film Classification. December 10, 2002. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Fergus M. Bordewich (December 2002). "Manhattan Mayhem". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- 1 2 Laura M. Holson (April 7, 2002). "2 Hollywood Titans Brawl Over a Gang Epic". The New York Times. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Laura M. Holson, Miramax Blinks, and a Double DiCaprio Vanishes, The New York Times, October 11, 2002; accessed July 15, 2010.

- ↑ Rick Lyman (February 12, 2003). "It's Harvey Weinstein's Turn to Gloat". The New York Times. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ↑ Dana Harris, Cathy Dunkley (May 15, 2001). "Miramax, Scorsese gang up". Variety. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Jeffrey Wells. "Hollywood Elsewhere: Gangs vs. Gangs". Retrieved 2010-12-20.

- 1 2 3 4 Cathy Dunkley (May 20, 2002). "Gangs of the Palais". Variety. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ↑ "Gangs all here for Scorsese". Chicago Sun-Times. December 15, 2002. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- 1 2 3 History News Network

- ↑ "Gangs of New York", HerbertAsbury.com; accessed October 5, 2016.

- ↑ "Bill the Butcher", HerbertAsbury.com; accessed October 5, 2016.

- ↑ Mixing Art and a Brutal History

- ↑ The New York Irish, Ronald H. Bayor and Timothy Meagher, eds. (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996)

- ↑ "19th century AD." Adolescence, Summer, 1995 by Ruskin Teeter.

- ↑ Paul S. Boyer (1992). "Urban Masses and Moral Order in America, 1820-1920". Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674931106

- ↑ Gangs, Crime, Smut, Violence. The New York Times. September 20, 1990.

- ↑ Riots, virtualny.cuny.edu; accessed October 5, 2016.

- ↑ Johnson, Michael."The New York Draft Riots". Reading the American Past, 2009 p. 295.

- ↑ Hamill, Pete. "Trampling city's history." New York Daily News; retrieved October 4, 2009.

- ↑ R. K. Chin, "A Journey Through Chinatown."

- ↑ "Gangs of New York". Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ↑ Gangs of New York Movie Reviews, Pictures – Rotten Tomatoes

- ↑ "Gangs of New York". metacritic.com. February 7, 2003. Retrieved July 10, 2011.

- ↑ Roger Ebert and Richard Roeper. "At the Movies: Gangs of New York". Retrieved 2002-12-20.

- ↑ Paul Clinton (December 19, 2002). "Review: Epic 'Gangs' Oscar-worthy effort". CNN. Retrieved 2002-12-19.

- ↑ Todd McCarthy (December 5, 2002). "Review: Gangs of New York Review". Variety. Retrieved 2002-12-05.

- ↑ "Gangs of New York negative reviews".

- 1 2 Bafta.org

- ↑ BFCA.org

- ↑ Chicagofilmcritics.org

- ↑ IMDb.com

- ↑ Ropeofscilicon.com

- ↑ IMDb.com

- ↑ LVFCS.org

- ↑ IMDb.org

- ↑ NYFCC.com

- ↑ Rottentomatoes.com Archived February 6, 2003, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ IMDb.com

- 1 2 IMDb.com

- ↑ Ropeofsilicon.com

- ↑ Sefca.com

- ↑ IMDb.com

- ↑ IMDb.com

- ↑ IMDb.com

- ↑ IMDb.com

- ↑ IMDb.com

- ↑ IMDb.com

- ↑ IMDb.Com

- ↑ Rottentomatoes.com

- ↑ IMDb.com

- ↑ IMDb.com

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-07-30.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Gangs of New York |

- Gangs of New York at the Internet Movie Database

- Gangs of New York at AllMovie

- Gangs of New York at Rotten Tomatoes

- Gangs of New York at Box Office Mojo