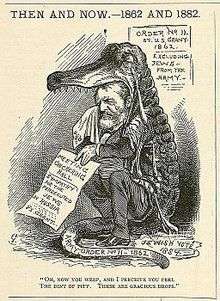

General Order No. 11 (1862)

General Order No. 11 was the title of an order issued by Major-General Ulysses S. Grant on December 17, 1862, during the American Civil War. It ordered the expulsion of all Jews in his military district, comprising areas of Tennessee, Mississippi, and Kentucky. The order was issued as part of a Union campaign against a black market in Southern cotton, which Grant thought was being run "mostly by Jews and other unprincipled traders."[1] In the war-zone, the United States licensed traders through the United States Army, which created a market for unlicensed ones. Union military commanders in the South were responsible for administering the trade licenses and trying to control the black market in Southern cotton, as well as for conducting the war. Grant issued the order in an effort to reduce corruption.

Following protests from Jewish community leaders and an outcry by members of Congress and the press, at President Abraham Lincoln's insistence, Grant revoked the General Order on January 17, 1863. During his campaign for the presidency in 1868, Grant claimed that he had issued the order without prejudice against Jews, but simply as a way to address a problem that certain Jews had caused.[2]

Background

During the war, the extensive cotton trade continued between the North and South. Northern textile mills in New York and New England were dependent on Southern cotton, while Southern plantation owners depended on the trade with the North for their economic survival. The U.S. Government permitted limited trade, licensed by the Treasury and the U.S. Army. Corruption flourished as unlicensed traders bribed Army officers to allow them to buy Southern cotton without a permit.[3] Jewish traders were among those involved in the cotton trade; some merchants had been active in the cotton business for generations in the South; others were more recent immigrants to the North.

As part of his command, Major General Ulysses S. Grant was responsible for issuing trade licenses in the Department of Tennessee, an administrative district of the Union Army that comprised the portions of Kentucky and Tennessee west of the Tennessee River, and Union-controlled areas of northern Mississippi. He was deeply engaged in prosecuting the campaign to capture the heavily defended Confederate-held city of Vicksburg, Mississippi and was committed to succeed. During this period, he tried several approaches to Vicksburg.

Grant resented having to deal with the distraction of the cotton trade. He perceived it as having endemic corruption: the highly lucrative trade resulted in a system where "every colonel, captain or quartermaster ... [was] in a secret partnership with some operator in cotton."[4] He issued a number of directives aimed at black marketeers.

On November 9, 1862, Grant sent an order to Major-General Stephen A. Hurlbut: "Refuse all permits to come south of Jackson for the present. The Israelites especially should be kept out."[5] The following day he instructed General Joseph Dana Webster: "Give orders to all the conductors on the [rail]road that no Jews are to be permitted to travel on the railroad southward from any point. They may go north and be encouraged in it; but they are such an intolerable nuisance that the department must be purged of them."[5] In a letter to General William Tecumseh Sherman, Grant wrote that his policy was occasioned "in consequence of the total disregard and evasion of orders by Jews."[6]

Grant tightened restrictions to try to reduce the illegal trade. On December 8, 1862, he issued General Order No. 2, mandating that "cotton-speculators, Jews and other Vagrants having not honest means of support, except trading upon the miseries of their Country ... will leave in twenty-four hours or they will be sent to duty in the trenches."[6] Nine days later, on December 17, 1862, he issued General Order No. 11 to strengthen his earlier prohibition.[4]

General James H. Wilson later suggested that the order was related to Grant's difficulties with his own father, Jesse Grant. He recounted,

He [Jesse Grant] was close and greedy. He came down into Tennessee with a Jew trader that he wanted his son to help, and with whom he was going to share the profits. Grant refused to issue a permit and sent the Jew flying, prohibiting Jews from entering the line.[7]

Wilson felt that Grant could not deal with the "lot of relatives who were always trying to use him" and perhaps attacked those he saw as their counterpart: opportunistic traders who were Jewish.[7] But Bertram Korn in his 1951 history suggested that the order was part of a pattern by Grant. "This was not the first discriminatory order [Grant] had signed [...] he was firmly convinced of the Jews' guilt and was eager to use any means of ridding himself of them."[5]

Text of Grant's Order

General Order No. 11 decreed as follows:

- The Jews, as a class violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department and also department orders, are hereby expelled from the Department [of the Tennessee] within twenty-four hours from the receipt of this order.

- Post commanders will see to it that all of this class of people be furnished passes and required to leave, and any one returning after such notification will be arrested and held in confinement until an opportunity occurs of sending them out as prisoners, unless furnished with permit from headquarters.

- No passes will be given these people to visit headquarters for the purpose of making personal application of trade permits.[8]

In a letter of the same date sent to Christopher Wolcott, the assistant United States Secretary of War, Grant explained his reasoning:

Sir,

I have long since believed that in spite of all the vigilance that can be infused into Post Commanders, that the Specie regulations of the Treasury Dept. have been violated, and that mostly by Jews and other unprincipled traders. So well satisfied of this have I been at this that I instructed the Commdg Officer at Columbus [Kentucky] to refuse all permits to Jews to come south, and frequently have had them expelled from the Dept. [of the Tennessee]. But they come in with their Carpet sacks in spite of all that can be done to prevent it. The Jews seem to be a privileged class that can travel any where. They will land at any wood yard or landing on the river and make their way through the country. If not permitted to buy Cotton themselves they will act as agents for someone else who will be at a Military post, with a Treasury permit to receive Cotton and pay for it in Treasury notes which the Jew will buy up at an agreed rate, paying gold.

There is but one way that I know of to reach this case. That is for Government to buy all the Cotton at a fixed rate and send it to Cairo, St Louis, or some other point to be sold. Then all traders, they are a curse to the Army, might be expelled.[9]

Reaction

The order went into immediate effect; Army officers ordered Jewish traders and their families in Holly Springs, Oxford, Mississippi, and Paducah, Kentucky to leave the territory. Grant may not have intended such results; his headquarters expressed no objection to the continued presence of Jewish sutlers, as opposed to cotton traders. But, the wording of the order addressed all Jews, regardless of occupation, and it was implemented accordingly.

A group of Jewish merchants from Paducah, Kentucky, led by Cesar J. Kaskel, sent a telegram to President Abraham Lincoln in which they condemned the order as "the grossest violation of the Constitution and our rights as good citizens under it". The telegram noted it would "place us . . . as outlaws before the world. We respectfully ask your immediate attention to this enormous outrage on all law and humanity ...."[9] Throughout the Union, Jewish groups protested and sent telegrams to the government in Washington, D.C.

The issue attracted significant attention in Congress and from the press. The Democrats condemned the order as part of what they saw as the US Government's systematic violation of civil liberties; they introduced a motion of censure against Grant in the Senate, attracting thirty votes in favor against seven opposed. Some newspapers supported Grant's action; the Washington Chronicle criticized Jews as "scavengers ... of commerce".[10] Most, however, were strongly opposed, with the New York Times denouncing the order as "humiliating" and a "revival of the spirit of the medieval ages."[10] Its editorial column called for the "utter reprobation" of Grant's order.[10]

Kaskel led a delegation to Washington, D.C., arriving on January 3, 1863. In Washington, he conferred with Jewish Republican Adolphus Solomons and a Cincinnati congressman, John A. Gurley. After meeting with Gurley, he went directly to the White House. Lincoln received the delegation and studied Kaskel's copies of General Order No. 11 and the specific order expelling Kaskel from Paducah. The President told General-in-Chief Henry Wager Halleck to have Grant revoke General Order No. 11, which Halleck did in the following message:

A paper purporting to be General Orders, No. 11, issued by you December 17, has been presented here. By its terms, it expells [sic] all Jews from your department. If such an order has been issued, it will be immediately revoked.[9]

One of Halleck's staff officers privately explained to Grant that the problem lay with the excessive scope of the order: "Had the word 'pedlar' been inserted after Jew I do not suppose any exception would have been taken to the order." According to Halleck, Lincoln had "no objection to [his] expelling traitors and Jew peddlers, which I suppose, was the object of your order; but as in terms proscribing an entire religious class, some of whom are fighting in our ranks, the President deemed it necessary to revoke it." The Republican politician Elihu B. Washburne defended Grant in similar terms. Grant's subordinates expressed concern about the order. One Jewish officer, Captain Philip Trounstine, of the Ohio cavalry, stationed in Moscow, Tennessee resigned in protest and Captain John C. Kelton, the assistant Adjutant-General of the Department of Missouri, wrote to Grant to note his order included all Jews, rather than focusing on "certain obnoxious individuals," and noted that many Jews served in the Union Army.[10][11] Grant formally revoked it on January 17, 1863.

On January 6, Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise of Cincinnati, leader of the Reform movement, led a delegation that met with Lincoln to express gratitude for his support. Lincoln said he was surprised that Grant had issued such a command and said, "to condemn a class is, to say the least, to wrong the good with the bad." Lincoln said he drew no distinction between Jew and Gentile and would allow no American to be wronged because of his religious affiliation.

Post-war repercussions

After the Civil War, General Order No. 11 became an issue in the presidential election of 1868 in which Grant stood as the Republican candidate. The Democrats raised the order as an issue, with the prominent Democrat and rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise urging fellow Jews to vote against Grant because of his alleged anti-semitism. Grant sought to distance himself from the order, saying "I have no prejudice against sect or race, but want each individual to be judged by his own merit."[12][13] He repudiated the controversial order, asserting it had been drafted by a subordinate and that he had signed it without reading, in the press of warfare.[4] In September 1868, Grant wrote in reply to Isaac N. Morris, a correspondent:

I do not pretend to sustain the order. At the time of its publication, I was incensed by a reprimand received from Washington for permitting acts which Jews within my lines were engaged in ... The order was issued and sent without any reflection and without thinking of the Jews as a set or race to themselves, but simply as persons who had successfully ... violated an order. ... I have no prejudice against sect or race, but want each individual to be judged by his own merit.[13][14]

The episode did not cause much long-term damage to Grant's relationship with the American Jewish community. He won the presidential election, taking the majority of the Jewish vote.[4]

Grant attends synagogue dedication

In his book When General Grant Expelled the Jews (2012) historian Jonathan Sarna argues that as president Grant became one of the greatest friends of Jews in American history. When he was president, he appointed more Jews to office than any previous president. He condemned atrocities against Jews in Europe, putting human rights on the American diplomatic agenda.[15]

In 1874, President Grant attended a dedication of the Adas Israel Congregation in Washington with all the members of his Cabinet. This was the first time an American President attended a synagogue service. Many historians have taken his action as part of his continuing effort to reconcile with the Jewish community.[16]

References

- ↑ John Y Simon (1979). The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 7: December 9, 1862 - March 31, 1863. SIU Press. p. 56. ISBN 9780809308804.

- ↑ Shelley Kapnek Rosenberg; et al. (2005). History of the Jews in America: Civil War Through the Rise of Zionism. Behrman House, Inc. pp. 22–23. ISBN 9780874417784.

- ↑ David S. Surdam, "Traders or traitors: Northern cotton trading during the Civil War," Business & Economic History, Winter 1999, Vol. 28 Issue 2, pp 299–310 online

- 1 2 3 4 See also Feldberg, M. (ed.), "General Grant's Infamy," Blessings of Freedom: Chapters in American Jewish History (American Jewish Historical Society 2002), at p. 119.

- 1 2 3 Bertram Korn, American Jewry and the Civil War (1951), p. 143.

- 1 2 Frederic Cople Jaher, A Scapegoat in the New Wilderness, p. 199. Harvard University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-674-79007-3

- 1 2 McFeely, p 124.

- ↑ "Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress: Order No. 11," Jewish Virtual Library.

- 1 2 3 Jacob Rader Marcus, The Jew in the American World: A Source Book, pp. 199–203. Wayne State University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8143-2548-3

- 1 2 3 4 Robert Michael, A Concise History Of American Antisemitism, p. 91. Rowman & Littlefield, 2005. ISBN 0-7425-4313-7

- ↑ Brooks D. Simpson, Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822–1865, p. 165. Houghton Mifflin Books, 2000. ISBN 0-395-65994-9

- ↑ Smith, Jean Edward (2001). Grant. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 459–460. ISBN 0-684-84927-5.

- 1 2 Simon, John Y. (1967). The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant: July 1, 1868-October 31, 1869. 19. Southern Illinois University Press. p. 37. ISBN 0-8093-1964-0. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ↑ Shelley Kapnek Rosenberg, Challenge and Change: Civil War Through the Rise of Zionism, p. 22. Behrman House, Inc., 2005. ISBN 0-87441-778-3

- ↑ Jonathon D. Sarna, When General Grant Expelled the Jews (2012)p xi, 89, 101

- ↑ "Precedents: Jews and Presidents". The Philadelphia Jewish Voice. 1 (2). August 2005.

External links

- "General Grant's Infamy", Jewish Virtual Library

- Order No. 11, Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress:

- "Grant, Lincoln, and General Order Number 11", American Presidents, December 2007

- "Gen. Grant's Uncivil War Against the Jews", The Jewish Week

- Little, Jane; McKenna, Bill (2012-05-16). "When General Grant expelled the Jews" (audio with images, 4:24). BBC News Online. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

Jonathan D Sarna tells this story in his new book, When General Grant Expelled the Jews.

.svg.png)