Geophysics

Geophysics /dʒiːoʊfɪzɪks/ is a subject of natural science concerned with the physical processes and physical properties of the Earth and its surrounding space environment, and the use of quantitative methods for their analysis. The term geophysics sometimes refers only to the geological applications: Earth's shape; its gravitational and magnetic fields; its internal structure and composition; its dynamics and their surface expression in plate tectonics, the generation of magmas, volcanism and rock formation.[1] However, modern geophysics organizations use a broader definition that includes the water cycle including snow and ice; fluid dynamics of the oceans and the atmosphere; electricity and magnetism in the ionosphere and magnetosphere and solar-terrestrial relations; and analogous problems associated with the Moon and other planets.[1][2][3]

Although geophysics was only recognized as a separate discipline in the 19th century, its origins date back to ancient times. The first magnetic compasses were made from lodestones, while more modern magnetic compasses played an important role in the history of navigation. The first seismic instrument was built in 132 BC. Isaac Newton applied his theory of mechanics to the tides and the precession of the equinox; and instruments were developed to measure the Earth's shape, density and gravity field, as well as the components of the water cycle. In the 20th century, geophysical methods were developed for remote exploration of the solid Earth and the ocean, and geophysics played an essential role in the development of the theory of plate tectonics.

Geophysics is applied to societal needs, such as mineral resources, mitigation of natural hazards and environmental protection.[2] Geophysical survey data are used to analyze potential petroleum reservoirs and mineral deposits, locate groundwater, find archaeological relics, determine the thickness of glaciers and soils, and assess sites for environmental remediation.

Physical phenomena

Geophysics is a highly interdisciplinary subject, and geophysicists contribute to every area of the Earth sciences. To provide a clearer idea of what constitutes geophysics, this section describes phenomena that are studied in physics and how they relate to the Earth and its surroundings.

Gravity

The gravitational pull of the Moon and Sun give rise to two high tides and two low tides every lunar day, or every 24 hours and 50 minutes. Therefore, there is a gap of 12 hours and 25 minutes between every high tide and between every low tide.[4]

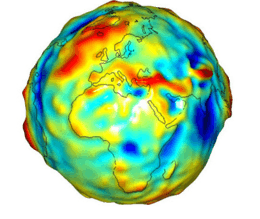

Gravitational forces make rocks press down on deeper rocks, increasing their density as the depth increases.[5] Measurements of gravitational acceleration and gravitational potential at the Earth's surface and above it can be used to look for mineral deposits (see gravity anomaly and gravimetry).[6] The surface gravitational field provides information on the dynamics of tectonic plates. The geopotential surface called the geoid is one definition of the shape of the Earth. The geoid would be the global mean sea level if the oceans were in equilibrium and could be extended through the continents (such as with very narrow canals).[7]

Heat flow

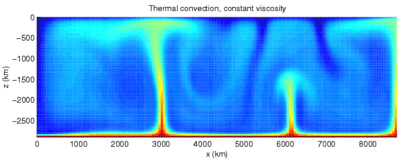

The Earth is cooling, and the resulting heat flow generates the Earth's magnetic field through the geodynamo and plate tectonics through mantle convection.[8] The main sources of heat are the primordial heat and radioactivity, although there are also contributions from phase transitions. Heat is mostly carried to the surface by thermal convection, although there are two thermal boundary layers – the core-mantle boundary and the lithosphere – in which heat is transported by conduction.[9] Some heat is carried up from the bottom of the mantle by mantle plumes. The heat flow at the Earth's surface is about 4.2 × 1013 W, and it is a potential source of geothermal energy.[10]

Vibrations

Seismic waves are vibrations that travel through the Earth's interior or along its surface. The entire Earth can also oscillate in forms that are called normal modes or free oscillations of the Earth. Ground motions from waves or normal modes are measured using seismographs. If the waves come from a localized source such as an earthquake or explosion, measurements at more than one location can be used to locate the source. The locations of earthquakes provide information on plate tectonics and mantle convection.[11][12]

Measurements of seismic waves are a source of information on the region that the waves travel through. If the density or composition of the rock changes suddenly, some waves are reflected. Reflections can provide information on near-surface structure.[6] Changes in the travel direction, called refraction, can be used to infer the deep structure of the Earth.[12]

Earthquakes pose a risk to humans. Understanding their mechanisms, which depend on the type of earthquake (e.g., intraplate or deep focus), can lead to better estimates of earthquake risk and improvements in earthquake engineering.[13]

Electricity

Although we mainly notice electricity during thunderstorms, there is always a downward electric field near the surface that averages 120 volts per meter.[14] Relative to the solid Earth, the atmosphere has a net positive charge due to bombardment by cosmic rays. A current of about 1800 amperes flows in the global circuit.[14] It flows downward from the ionosphere over most of the Earth and back upwards through thunderstorms. The flow is manifested by lightning below the clouds and sprites above.

A variety of electric methods are used in geophysical survey. Some measure spontaneous potential, a potential that arises in the ground because of man-made or natural disturbances. Telluric currents flow in Earth and the oceans. They have two causes: electromagnetic induction by the time-varying, external-origin geomagnetic field and motion of conducting bodies (such as seawater) across the Earth's permanent magnetic field.[15] The distribution of telluric current density can be used to detect variations in electrical resistivity of underground structures. Geophysicists can also provide the electric current themselves (see induced polarization and electrical resistivity tomography).

Electromagnetic waves

Electromagnetic waves occur in the ionosphere and magnetosphere as well as the Earth's outer core. Dawn chorus is believed to be caused by high-energy electrons that get caught in the Van Allen radiation belt. Whistlers are produced by lightning strikes. Hiss may be generated by both. Electromagnetic waves may also be generated by earthquakes (see seismo-electromagnetics).

In the Earth's outer core, electric currents in the highly conductive liquid iron create magnetic fields by electromagnetic induction (see geodynamo). Alfvén waves are magnetohydrodynamic waves in the magnetosphere or the Earth's core. In the core, they probably have little observable effect on the geomagnetic field, but slower waves such as magnetic Rossby waves may be one source of geomagnetic secular variation.[16]

Electromagnetic methods that are used for geophysical survey include transient electromagnetics and magnetotellurics.

Magnetism

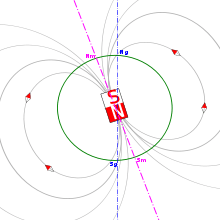

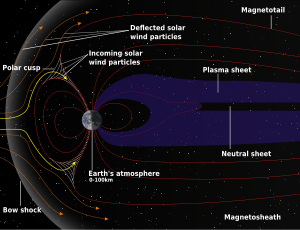

The Earth's magnetic field protects the Earth from the deadly solar wind and has long been used for navigation. It originates in the fluid motions of the Earth's outer core (see geodynamo).[16] The magnetic field in the upper atmosphere gives rise to the auroras.[17]

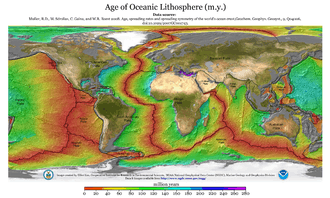

The Earth's field is roughly like a tilted dipole, but it changes over time (a phenomenon called geomagnetic secular variation). Mostly the geomagnetic pole stays near the geographic pole, but at random intervals averaging 440,000 to a million years or so, the polarity of the Earth's field reverses. These geomagnetic reversals, analyzed within a Geomagnetic Polarity Time Scale, contain 184 polarity intervals in the last 83 million years, with change in frequency over time, with the most recent brief complete reversal of the Laschamp event occurring 41,000 years ago during the last glacial period. Geologists observed geomagnetic reversal recorded in volcanic rocks, through magnetostratigraphy correlation (see natural remanent magnetization) and their signature can be seen as parallel linear magnetic anomaly stripes on the seafloor. These stripes provide quantitative information on seafloor spreading, a part of plate tectonics. They are the basis of magnetostratigraphy, which correlates magnetic reversals with other stratigraphies to construct geologic time scales.[18] In addition, the magnetization in rocks can be used to measure the motion of continents.[16]

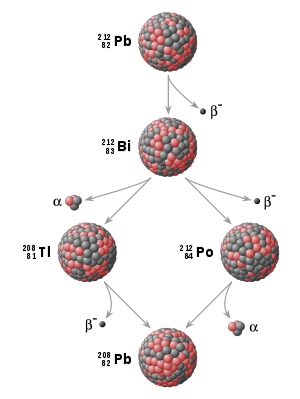

Radioactivity

Radioactive decay accounts for about 80% of the Earth's internal heat, powering the geodynamo and plate tectonics.[19] The main heat-producing isotopes are potassium-40, uranium-238, uranium-235, and thorium-232.[20] Radioactive elements are used for radiometric dating, the primary method for establishing an absolute time scale in geochronology. Unstable isotopes decay at predictable rates, and the decay rates of different isotopes cover several orders of magnitude, so radioactive decay can be used to accurately date both recent events and events in past geologic eras.[21] Radiometric mapping using ground and airborne gamma spectrometry can be used to map the concentration and distribution of radioisotopes near the Earth's surface, which is useful for mapping lithology and alteration.[22][23]

Fluid dynamics

Fluid motions occur in the magnetosphere, atmosphere, ocean, mantle and core. Even the mantle, though it has an enormous viscosity, flows like a fluid over long time intervals (see geodynamics). This flow is reflected in phenomena such as isostasy, post-glacial rebound and mantle plumes. The mantle flow drives plate tectonics and the flow in the Earth's core drives the geodynamo.[16]

Geophysical fluid dynamics is a primary tool in physical oceanography and meteorology. The rotation of the Earth has profound effects on the Earth's fluid dynamics, often due to the Coriolis effect. In the atmosphere it gives rise to large-scale patterns like Rossby waves and determines the basic circulation patterns of storms. In the ocean they drive large-scale circulation patterns as well as Kelvin waves and Ekman spirals at the ocean surface.[24] In the Earth's core, the circulation of the molten iron is structured by Taylor columns.[16]

Waves and other phenomena in the magnetosphere can be modeled using magnetohydrodynamics.

Mineral physics

The physical properties of minerals must be understood to infer the composition of the Earth's interior from seismology, the geothermal gradient and other sources of information. Mineral physicists study the elastic properties of minerals; their high-pressure phase diagrams, melting points and equations of state at high pressure; and the rheological properties of rocks, or their ability to flow. Deformation of rocks by creep make flow possible, although over short times the rocks are brittle. The viscosity of rocks is affected by temperature and pressure, and in turn determines the rates at which tectonic plates move (see geodynamics).[5]

Water is a very complex substance and its unique properties are essential for life.[25] Its physical properties shape the hydrosphere and are an essential part of the water cycle and climate. Its thermodynamic properties determine evaporation and the thermal gradient in the atmosphere. The many types of precipitation involve a complex mixture of processes such as coalescence, supercooling and supersaturation.[26] Some precipitated water becomes groundwater, and groundwater flow includes phenomena such as percolation, while the conductivity of water makes electrical and electromagnetic methods useful for tracking groundwater flow. Physical properties of water such as salinity have a large effect on its motion in the oceans.[24]

The many phases of ice form the cryosphere and come in forms like ice sheets, glaciers, sea ice, freshwater ice, snow, and frozen ground (or permafrost).[27]

Regions of the Earth

Size and form of the Earth

The Earth is roughly spherical, but it bulges towards the Equator, so it is roughly in the shape of an ellipsoid (see Earth ellipsoid). This bulge is due to its rotation and is nearly consistent with an Earth in hydrostatic equilibrium. The detailed shape of the Earth, however, is also affected by the distribution of continents and ocean basins, and to some extent by the dynamics of the plates.[7]

Structure of the interior

Evidence from seismology, heat flow at the surface, and mineral physics is combined with the Earth's mass and moment of inertia to infer models of the Earth's interior – its composition, density, temperature, pressure. For example, the Earth's mean specific gravity (5.515) is far higher than the typical specific gravity of rocks at the surface (2.7–3.3), implying that the deeper material is denser. This is also implied by its low moment of inertia ( 0.33 M R2, compared to 0.4 M R2 for a sphere of constant density). However, some of the density increase is compression under the enormous pressures inside the Earth. The effect of pressure can be calculated using the Adams–Williamson equation. The conclusion is that pressure alone cannot account for the increase in density. Instead, we know that the Earth's core is composed of an alloy of iron and other minerals.[5]

Reconstructions of seismic waves in the deep interior of the Earth show that there are no S-waves in the outer core. This indicates that the outer core is liquid, because liquids cannot support shear. The outer core is liquid, and the motion of this highly conductive fluid generates the Earth's field (see geodynamo). The inner core, however, is solid because of the enormous pressure.[7]

Reconstruction of seismic reflections in the deep interior indicate some major discontinuities in seismic velocities that demarcate the major zones of the Earth: inner core, outer core, mantle, lithosphere and crust. The mantle itself is divided into the upper mantle, transition zone, lower mantle and D′′ layer. Between the crust and the mantle is the Mohorovičić discontinuity.[7]

The seismic model of the Earth does not by itself determine the composition of the layers. For a complete model of the Earth, mineral physics is needed to interpret seismic velocities in terms of composition. The mineral properties are temperature-dependent, so the geotherm must also be determined. This requires physical theory for thermal conduction and convection and the heat contribution of radioactive elements. The main model for the radial structure of the interior of the Earth is the preliminary reference Earth model (PREM). Some parts of this model have been updated by recent findings in mineral physics (see post-perovskite) and supplemented by seismic tomography. The mantle is mainly composed of silicates, and the boundaries between layers of the mantle are consistent with phase transitions.[5]

The mantle acts as a solid for seismic waves, but under high pressures and temperatures it deforms so that over millions of years it acts like a liquid. This makes plate tectonics possible. Geodynamics is the study of the fluid flow in the mantle and core.

Magnetosphere

If a planet's magnetic field is strong enough, its interaction with the solar wind forms a magnetosphere. Early space probes mapped out the gross dimensions of the Earth's magnetic field, which extends about 10 Earth radii towards the Sun. The solar wind, a stream of charged particles, streams out and around the terrestrial magnetic field, and continues behind the magnetic tail, hundreds of Earth radii downstream. Inside the magnetosphere, there are relatively dense regions of solar wind particles called the Van Allen radiation belts.[17]

Methods

Geodesy

Geophysical measurements are generally at a particular time and place. Accurate measurements of position, along with earth deformation and gravity, are the province of geodesy. While geodesy and geophysics are separate fields, the two are so closely connected that many scientific organizations such as the American Geophysical Union, the Canadian Geophysical Union and the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics encompass both.[28]

Absolute positions are most frequently determined using the global positioning system (GPS). A three-dimensional position is calculated using messages from four or more visible satellites and referred to the 1980 Geodetic Reference System. An alternative, optical astronomy, combines astronomical coordinates and the local gravity vector to get geodetic coordinates. This method only provides the position in two coordinates and is more difficult to use than GPS. However, it is useful for measuring motions of the Earth such as nutation and Chandler wobble. Relative positions of two or more points can be determined using very-long-baseline interferometry.[28][29][30]

Gravity measurements became part of geodesy because they were needed to related measurements at the surface of the Earth to the reference coordinate system. Gravity measurements on land can be made using gravimeters deployed either on the surface or in helicopter flyovers. Since the 1960s, the Earth's gravity field has been measured by analyzing the motion of satellites. Sea level can also be measured by satellites using radar altimetry, contributing to a more accurate geoid.[28] In 2002, NASA launched the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE), wherein two twin satellites map variations in Earth's gravity field by making measurements of the distance between the two satellites using GPS and a microwave ranging system. Gravity variations detected by GRACE include those caused by changes in ocean currents; runoff and ground water depletion; melting ice sheets and glaciers.[31]

Space probes

Space probes made it possible to collect data from not only the visible light region, but in other areas of the electromagnetic spectrum. The planets can be characterized by their force fields: gravity and their magnetic fields, which are studied through geophysics and space physics.

Measuring the changes in acceleration experienced by spacecraft as they orbit has allowed fine details of the gravity fields of the planets to be mapped. For example, in the 1970s, the gravity field disturbances above lunar maria were measured through lunar orbiters, which led to the discovery of concentrations of mass, mascons, beneath the Imbrium, Serenitatis, Crisium, Nectaris and Humorum basins.[32]

History

Geophysics emerged as a separate discipline only in the 19th century, from the intersection of physical geography, geology, astronomy, meteorology, and physics.[33][34] However, many geophysical phenomena – such as the Earth's magnetic field and earthquakes – have been investigated since the ancient era.

Ancient and classical eras

The magnetic compass existed in China back as far as the fourth century BC. It was used as much for feng shui as for navigation on land. It was not until good steel needles could be forged that compasses were used for navigation at sea; before that, they could not retain their magnetism long enough to be useful. The first mention of a compass in Europe was in 1190 AD.[35]

In circa 240 BC, Eratosthenes of Cyrene deduced that the Earth was round and measured the circumference of the Earth, using trigonometry and the angle of the Sun at more than one latitude in Egypt. He developed a system of latitude and longitude.[36]

Perhaps the earliest contribution to seismology was the invention of a seismoscope by the prolific inventor Zhang Heng in 132 AD.[37] This instrument was designed to drop a bronze ball from the mouth of a dragon into the mouth of a toad. By looking at which of eight toads had the ball, one could determine the direction of the earthquake. It was 1571 years before the first design for a seismoscope was published in Europe, by Jean de la Hautefeuille. It was never built.[38]

Beginnings of modern science

One of the publications that marked the beginning of modern science was William Gilbert's De Magnete (1600), a report of a series of meticulous experiments in magnetism. Gilbert deduced that compasses point north because the Earth itself is magnetic.[16]

In 1687 Isaac Newton published his Principia, which not only laid the foundations for classical mechanics and gravitation but also explained a variety of geophysical phenomena such as the tides and the precession of the equinox.[39]

The first seismometer, an instrument capable of keeping a continuous record of seismic activity, was built by James Forbes in 1844.[38]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Sheriff 1991

- 1 2 IUGG 2011

- ↑ AGU 2011

- ↑ Ross 1995, pp. 236–242

- 1 2 3 4 Poirier 2000

- 1 2 Telford, Geldart & Sheriff 1990

- 1 2 3 4 Lowrie 2004

- ↑ Davies 2001

- ↑ Fowler 2005

- ↑ Pollack, Hurter & Johnson 1993

- ↑ Shearer, Peter M. (2009). Introduction to seismology (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521708425.

- 1 2 Stein & Wysession 2003

- ↑ Bozorgnia & Bertero 2004

- 1 2 Harrison & Carslaw 2003

- ↑ Lanzerotti & Gregori 1986

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Merrill, McElhinny & McFadden 1996

- 1 2 Kivelson & Russell 1995

- ↑ Opdyke & Channell 1996

- ↑ Turcotte & Schubert 2002

- ↑ Sanders 2003

- ↑ Renne, Ludwig & Karner 2000

- ↑ "Radiometrics". Geoscience Australia. Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ↑ "Interpreting radiometrics". Natural Resource Management. Department of Agriculture and Food, Government of Western Australia. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- 1 2 Pedlosky 1987

- ↑ Sadava et al. 2009

- ↑ Sirvatka 2003

- ↑ CFG 2011

- 1 2 3 National Research Council (U.S.). Committee on Geodesy 1985

- ↑ Defense Mapping Agency 1984

- ↑ Torge 2001

- ↑ CSR 2011

- ↑ Muller & Sjogren 1968

- ↑ Hardy & Goodman 2005

- ↑ Schröder, W. (2010). "History of geophysics". Acta Geodaetica et Geophysica Hungarica. 45 (2): 253–261. doi:10.1556/AGeod.45.2010.2.9.

- ↑ Temple 2006, pp. 162–166

- ↑ Eratosthenes 2010

- ↑ Temple 2006, pp. 177–181

- 1 2 Dewey & Byerly 1969

- ↑ Newton 1999 Section 3

References

- American Geophysical Union (2011). "Our Science". About AGU. Retrieved September 2011. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - "About IUGG". 2011. Retrieved September 2011. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - "AGUs Cryosphere Focus Group". 2011. Retrieved September 2011. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Bozorgnia, Yousef; Bertero, Vitelmo V. (2004). Earthquake Engineering: From Engineering Seismology to Performance-Based Engineering. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-1439-1.

- Chemin, Jean-Yves; Desjardins, Benoit; Gallagher, Isabelle; Grenier, Emmanuel (2006). Mathematical geophysics: an introduction to rotating fluids and the Navier-Stokes equations. Oxford lecture series in mathematics and its applications. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-857133-X.

- Davies, Geoffrey F. (2001). Dynamic Earth: Plates, Plumes and Mantle Convection. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59067-1.

- Dewey, James; Byerly, Perry (1969). "The Early History of Seismometry (to 1900)". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 59 (1): 183–227.

- Defense Mapping Agency (1984) [1959]. Geodesy for the Layman (Technical report). National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. TR 80-003. Retrieved September 2011. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Eratosthenes (2010). Eratosthenes' "Geography". Fragments collected and translated, with commentary and additional material by Duane W. Roller. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14267-8.

- Fowler, C.M.R. (2005). The Solid Earth: An Introduction to Global Geophysics (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-89307-0.

- "GRACE: Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment". University of Texas at Austin Center for Space Research. 2011. Retrieved September 2011. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Hardy, Shaun J.; Goodman, Roy E. (2005). "Web resources in the history of geophysics". American Geophysical Union. Archived from the original on 27 April 2013. Retrieved September 2011. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Harrison, R. G.; Carslaw, K. S. (2003). "Ion-aerosol-cloud processes in the lower atmosphere". Reviews of Geophysics. 41 (3): 1012. Bibcode:2003RvGeo..41.1012H. doi:10.1029/2002RG000114.

- Kivelson, Margaret G.; Russell, Christopher T. (1995). Introduction to Space Physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45714-9.

- Lanzerotti, Louis J.; Gregori, Giovanni P. (1986). "Telluric currents: the natural environment and interactions with man-made systems". In Geophysics Study Committee; Geophysics Research Forum; Commission on Physical Sciences, Mathematics and Resources; National Research Council. The Earth's electrical environment. The Earth's Electrical Environment. National Academy Press. pp. 232–258. ISBN 0-309-03680-1.

- Lowrie, William (2004). Fundamentals of Geophysics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-46164-2.

- Merrill, Ronald T.; McElhinny, Michael W.; McFadden, Phillip L. (1998). The Magnetic Field of the Earth: Paleomagnetism, the Core, and the Deep Mantle. International Geophysics Series. 63. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0124912458.

- Muller, Paul; Sjogren, William (1968). "Mascons: lunar mass concentrations". Science. 161 (3842): 680–684. Bibcode:1968Sci...161..680M. doi:10.1126/science.161.3842.680. PMID 17801458.

- National Research Council (U.S.). Committee on Geodesy (1985). Geodesy: a look to the future (pdf) (Report). National Academies.

- Newton, Isaac (1999). The Principia, Mathematical principles of natural philosophy. A new translation by I Bernard Cohen and Anne Whitman, preceded by "A Guide to Newton's Principia" by I Bernard Cohen. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08816-0.

- Opdyke, Neil D.; Channell, James T. (1996). Magnetic Stratigraphy. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-527470-X.

- Pedlosky, Joseph (1987). Geophysical Fluid Dynamics (Second ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-96387-1.

- Poirier, Jean-Paul (2000). Introduction to the Physics of the Earth's Interior. Cambridge Topics in Mineral Physics & Chemistry. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66313-X.

- Pollack, Henry N.; Hurter, Suzanne J.; Johnson, Jeffrey R. (1993). "Heat flow from the Earth's interior: Analysis of the global data set". Reviews of Geophysics. 31 (3): 267–280. Bibcode:1993RvGeo..31..267P. doi:10.1029/93RG01249.

- Renne, P.R.; Ludwig, K.R.; Karner, D.B. (2000). "Progress and challenges in geochronology". Science Progress. 83: 107–121. PMID 10800377.

- Richards, M. A.; Duncan, R. A.; Courtillot, V. E. (1989). "Flood Basalts and Hot-Spot Tracks: Plume Heads and Tails". Science. 246 (4926): 103–107. Bibcode:1989Sci...246..103R. doi:10.1126/science.246.4926.103. PMID 17837768.

- Ross, D.A. (1995). Introduction to Oceanography. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-13-491408-2.

- Sadava, David; Heller, H. Craig; Hillis, David M.; Berenbaum, May (2009). Life: The Science of Biology. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4292-1962-4.

- Sanders, Robert (10 December 2003). "Radioactive potassium may be major heat source in Earth's core". UC Berkeley News. Retrieved 28 February 2007.

- Sirvatka, Paul (2003). "Cloud Physics: Collision/Coalescence; The Bergeron Process". College of DuPage. Retrieved August 2011. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Sheriff, Robert E. (1991). "Geophysics". Encyclopedic Dictionary of Exploration Geophysics (3rd ed.). Society of Exploration. ISBN 978-1-56080-018-7.

- Stein, Seth; Wysession, Michael (2003). An introduction to seismology, earthquakes, and earth structure. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-86542-078-5.

- Telford, William Murray; Geldart, L. P.; Sheriff, Robert E. (1990). Applied geophysics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33938-4.

- Temple, Robert (2006). The Genius of China. Andre Deutsch. ISBN 0-671-62028-2.

- Torge, W. (2001). Geodesy (3rd ed.). Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 0-89925-680-5.

- Turcotte, Donald Lawson; Schubert, Gerald (2002). Geodynamics (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66624-4.

- Verhoogen, John (1980). Energetics of the Earth. National Academy Press. ISBN 978-0-309-03076-2.

External links

- A reference manual for near-surface geophysics techniques and applications

- Commission on Geophysical Risk and Sustainability (GeoRisk), International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics (IUGG)

- Study of the Earth's Deep Interior, a Committee of IUGG

- Union Commissions (IUGG)

- USGS Geomagnetism Program

- Career crate: Seismic processor

- Society of Exploration Geophysicists