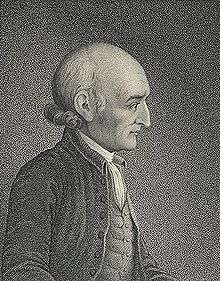

George Wythe

| George Wythe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

1726 Chesterville, Elizabeth City County, Virginia, British America |

| Died |

June 8, 1806 (aged 79–80) Richmond, Virginia, U.S. |

| Resting place | St. John's Churchyard, Richmond, Virginia, U.S. |

| Known for | Signer of the United States Declaration of Independence |

| Signature | |

|

| |

George Wythe (pronounced WITH) (1726 – June 8, 1806) was the first American law professor, a noted classics scholar and Virginia judge, as well as a prominent opponent of slavery.[1] The first of the seven Virginia signatories of the United States Declaration of Independence, Wythe served as one of Virginia's representatives to the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention.[2] Wythe taught and was a mentor to Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall, Henry Clay and other men who became American leaders.[3]

Early life and education

Wythe was born in 1726 at Chesterville, the plantation operated by three generations of the Wythe family in what was then Elizabeth City County but is now Hampton, Virginia. His maternal great-grandfather was George Keith, a Quaker minister and early opponent of African slavery, who returned to the Church of England but was sent back as a missionary to the East Coast before ultimately returning to England.[4] His mother, Margaret Walker of Kecoughtan, a learned woman probably raised as a Quaker, instilled a love of learning in her son. In his later years, Wythe became known for his outdated Quaker dress, as well as his gentle manner, which could cause even a surly dog to "unbend and wag his tail."[5] After the early death of his father, Wythe probably attended grammar school in Williamsburg before beginning legal training in the office of his uncle, Stephen Dewey, in Prince George County.

Career

Wythe was admitted to the bar in Elizabeth City County in 1746, the same year in which his mother died.[6] He then moved to Spotsylvania County to begin legal practice in several Piedmont counties. He soon married the daughter of his mentor, Zachary Lewis. However, Ann Wythe died on August 10, 1748, about eight months after their Christmas season marriage. The childless and bereaved widower soon returned to Williamsburg. There, Wythe made law and scholarship his life, as he began what would become a distinguished career in public service. His motto was "Secundis dubiisque rectus", translated as "Upright in prosperity and perils."[7]

Colonial politician, lawyer and mentor

In October 1748, family connections (Benjamin Waller was related to Zachary Lewis) probably helped Wythe secure his first government job, as clerk to two powerful committees of the House of Burgesses, Privileges and Elections and Propositions and Grievances. Wythe also continued to practice law before those committees and the General Court in Williamsburg, as was permitted at the time. In 1750, Wythe was first elected as one of Williamsburg's aldermen.[8] Wythe also briefly served as the king's attorney general in 1754–1755, appointed by lieutenant governor Robert Dinwiddie while Peyton Randolph traveled to London on the burgesses' behalf to appeal Dinwiddie's charging a one pistole fee to affix an official seal to land patents. Wythe resigned when Randolph returned from his unsuccessful mission. Lieutenant governor Robert Dinwiddie returned to England less than three years after Peyton Randolph's return.[9]

Meanwhile, Wythe began his legislative career, while still maintaining a private law practice. In the session of August 22, 1754, Wythe replaced the deceased Armistead Burwell as the burgess representing Williamsburg.[10] In 1755, Wythe's elder brother, Thomas, died, childless. Wythe inherited the family's Chesterville plantation, and was soon appointed to his brother's (and formerly his father's) place on the Elizabeth City County court.

However, Wythe probably continued to live in Williamsburg, for his legislative work continued, and he married Elizabeth Taliaferro. Her father, planter Richard Taliaferro, built a house for them in Williamsburg, which is still called the George Wythe House even though Wythe only had a life estate in the property after Taliaferro's death. Wythe served as Williamsburg's delegate through the sessions of 1754 and 1755 (but not in the sessions of the Assembly of 1756–1758).[11] During that gap, Wythe was reappointed clerk to the committees on Privileges and Elections and Propositions and Grievances, as well as to the Committee for Courts of Justice, and in 1759 to the Committee of Correspondence (with the colony's agent in England).[12] In 1759, The College of William and Mary elected Wythe as its burgess to replace Peyton Randolph, and reelected Wythe in 1760 and 1761.[13] Wythe helped oversee defense expenditures related to the French and Indian War,[14] and later with Richard Henry Lee retirement of the paper money issued to fund the war, which became a scandal in 1766, as discussed below. For the Assemblies of 1761, 1765 and 1767, Wythe was one of the two burgesses representing Elizabeth City County.[15]

Although known for his modesty and quiet dignity, Wythe eventually gained a radical reputation for his opposition to the Stamp Act of 1765 and later attempts by the British government to regulate the overseas colony. Meanwhile, Wythe maintained close friendships with successive Governors, Francis Fauquier and Norborne Berkeley, 4th Baron Botetourt. Wythe also earned a reputation for personal integrity, which years later led Rev. Lee Massey to call Wythe "the only honest lawyer I ever knew."[16] Fauquier, Wythe and college professor William Small often socialized together—conversing about philosophy, natural history, languages, history and other matters. In 1762, Small suggested Wythe supervise the legal training of a star student, Thomas Jefferson, which had profound impact that went beyond their lives.[17]

In the summer of 1766, three events occurred which profoundly influenced Wythe, Jefferson and several other Virginians who became Founding Fathers and insisted upon the separation of powers between three branches of the new government. When John Robinson, the powerful speaker of the House of Burgesses, died, his estate was nearly insolvent (with many debts, as well as outstanding loans), and the accounts Robinson kept as Treasurer were also irregular. Instead of destroying redeemed paper currency after the French and Indian War, Robinson had lent it to his political supporters (fellow southern Virginia planters). Keeping the money in circulation helped these allies pay their own debts, but also tended to devalue the currency, as well as defied the redemption laws the legislature had passed. Robinson's executors kept the names of the politically powerful loan beneficiaries secret for decades, but did not manage to end the John Robinson estate scandal before the century itself ended.[18] Moreover, on June 20, 1766, Colonel John Chiswell, father of Robinson's widow and business partner of Robinson, governor Fauquier and William Byrd III, killed merchant Robert Routledge (to whom he owed money) at the Cumberland Court House. Indicted for murder, Chiswell was brought under armed guard to Williamsburg for trial in the next session of the General Court (which included many men from distant counties who also served as Burgesses and was thus usually held at the same time). Before the group reached the Williamsburg jail, three judges (John Blair, Presley Thornton and Byrd) stopped them on the street and allowed Chiswell to post bail until September, since the next court session began in October.

Meanwhile, the publisher of the Virginia Gazette had died. When it became clear in the spring of 1766 that the Stamp Act was not going to be enforced, two printers set up shops in Williamsburg. Both papers thrived in the ensuing controversies.[19] On July 4, Judge Blair explained in a published letter that the judges had relied upon assurances of "three eminent Lawyers" that they could grant Chiswell bail, as well as two depositions that Routledge had run himself on Chiswell's sword, while stressing that the high bail of 6,000 pounds sterling could be recovered should Chiswell fail to show for trial.[20] In response, 'Dikephilos' wrote that his own investigation agreed that Routledge had been drunk, but Chiswell was not, and further that neither deponent favoring Chiswell had witnessed the brawl. He predicted popular violence if the trial unfairly favored the aristocratic defendant. More published letters followed. On August 1, Wythe identified himself in print as one of the consulted lawyers and said his opinion had been limited to the legal bail issue. After Chiswell returned to Williamsburg in September, his attorney John Wayles published the two depositions given to the judges, which proved to be from Wayles himself and the Cumberland undersheriff. Judge Blair was furious when Wayles added a detail to the published copy of his own deposition (which he had gotten from the court records), apparently in order to track the undersheriff's deposition.[21] Judge Byrd, on the other hand, joined with Wayles to demand a libel indictment against Col. Robert Bolling, Jr., claiming Bolling wrote the anonymous criticism of the bailment published on July 11.[22] The grand jury refused, issuing a no-bill instead. However, Wythe's sterling reputation may have been tarnished.[23] When the assembly reconvened, Robert Carter Nicholas was appointed treasurer, Peyton Randolph became speaker, and his brother John Randolph became king's attorney general, a post to which Wythe had aspired. Chiswell died unexpectedly in his Williamsburg home on October 15, before his trial could begin. Jefferson decades later in his Kentucky Resolution echoed the anononymous 'Virginia Gazette' writer of September 12, 1766, who stated, "Distrust, the parent of security, is a political virtue of unspeakable utility."[24]

Wythe continued his thriving legal practice with Jefferson's assistance. In 1767, Wythe introduced Jefferson to the bar of the General Court, and was himself appointed clerk to the House of Burgesses. The following year, Wythe wrote the colony's London agent to secure copies of the burgesses' complete journals from the colony's founding until 1752, which were supposed to be transmitted annually to the king, secretary of state and Lords of Trade, stressing "it be not made public nor attended with great expense."[25] The secrecy may have related to continuing unrest in Massachusetts against the Townshend Acts or the administrative interregnum between Fauquier's death in March and Botetourt's arrival in October.[26] Wythe also ordered printed journals of the House of Commons and case law books from London. Wythe's social standing remained high, for fellow aldermen elected him Williamsburg's mayor for the 1768 to 1769 term. Fellow parishioners also elected Wythe to the vestry of Bruton Parish Church in 1769.

Botetourt arrived on October 26, 1768, as Virginia's first governor to rule the colony in person in sixty years. Although Botetourt dissolved the House of Burgesses the following spring, following a royal order to all colonial governors after protests in Massachusetts against the Townshend Acts, Wythe managed to stave off the governor's clerk so the delegates could publish a resolution of protest before receiving the dissolution order.[27] The burgesses then repaired to the Raleigh Tavern, where they passed the Virginia Nonimportation Resolutions on May 18, 1769. Some speculate that Wythe's own status as clerk kept his name off that document. In any event, the burgesses gave a spectacular party for Botetourt that Christmas, and his funeral ceremonies the following fall were the most elaborate in Virginia history. They also voted for a marble statue of the governor to be erected at public expense.[28]

Revolutionary

The next royal Governor, John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, brought Wythe and Virginia to and past the brink of revolution. Dunmore arrived in Williamsburg from New York on September 26, 1771. Rumors of his year as the other colony's governor, which included accusations of graft and companions roughing up local judges, soon followed.[29] Although some cheered his military offensive against the Indians (later known as Lord Dunmore's War) as strengthening Virginia's land claims, Wythe, Jefferson and many others soon took offense at Dunmore's haughty personality.[30] Dunmore attempted to govern without the burgesses, but counterfeiting and other money troubles forced him to convene the Assembly in early 1773. Delegates began by voicing concerns that suspects in the burning of the revenue vessel 'Gaspee' in Rhode Island could be tried in England. When on March 3, 1773 they resolved to establish a Committee of Correspondence, Dunmore prorouged (postponed) the assembly.[31] Moreover, Parliament passed the Tea Act in May, 1773 and on December 16, the Sons of Liberty had the Boston Tea Party. Dunmore tried to reconvene the delegates the following May. On May 24, 1774, the House of Burgesses passed a resolution declaring June 1 as a day of fasting and prayer, which resolution Wythe signed and posted. Enraged, Dunmore dissolved the assembly. The delegates moved to conduct their business at the Raleigh Tavern, and meet again mid-March in Richmond.

Wythe attended the Second Virginia Convention as Williamsburg's representative. The meeting was held in St. John's Episcopal Church, in whose graveyard Wythe would be buried about three decades later. Patrick Henry stirred the delegates with his "Give me liberty or give me death" speech. The delegates agreed to convene militia, and the prospect of armed resistance caused Dunmore to try to remove military supplies from Williamsburg to the British naval ships offshore. Wythe enlisted in the militia immediately upon returning home.[32] In the Gunpowder Incident of April 20, 1775, Peyton Randolph, Robert Carter Nicholas and Carter Braxton helped diffuse Henry's attempt to force return of the gunpowder by negotiating payment from Dunmore.

On May 10, 1775, the Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia. When war seemed inevitable, Wythe was elected as Virginia's delegate to replace George Washington, who took command of the continental forces. George and Elizabeth Wythe moved to Philadelphia by September, and were inoculated against smallpox, as were fellow delegate Francis Lightfoot Lee and his lady and others. By October, Thomas Jefferson had rejoined the Congress to work with his former teacher and the other delegates, although personal tragedy forced him to leave for five months in the winter and spring. Wythe accepted many assignments relating to military, currency and other matters. He, John Dickinson and John Jay also went to New Jersey that winter and convinced that colony's assembly to maintain a united front.[34] When petitions and other attempts failed to resolve the crisis by the following summer, all while Dunmore's raiders harassed Virginia settlements from its waterways, Wythe moved and then voted in favor of the resolution for independence that Jefferson had drafted upon his return. His fellow Virginia delegates in Philadelphia held Wythe in such esteem, that they left the first space open for Wythe when they signed the Declaration of Independence.[35] Moreover, John Adams, who did not like many Virginians, thought so highly of Wythe that he wrote 'Thoughts on Government' concerning establishing constitutions for state governments after the war.[36][37] Earlier in the session, Wythe also exchanged humorous verses with his friend delegate William Ellery of Rhode Island despite their political differences.[38] Wythe thus signed the Declaration of Independence upon his (and his wife's) return to Philadelphia in September. The signers' names were not made public until the following January, for all knew the declaration was an act of treason, punishable by death should their rebellion fail.[39]

As did many of the founding fathers, Wythe paid dearly for supporting independence. The farmer to whom he had leased Chesterville, Hamilton Usher St. George, proved to be a British spy, although acquitted of those charges on April 23, 1776.[40] As documented in British archives, St. George invited British raiding parties that not only damaged neighboring plantations, but also Williamsburg and other settlements along the James River. British troops encamped at Portsmouth went on raids such as the skirmish at Waters Creek. In January 1781, Benedict Arnold led British raiders that forced Governor Thomas Jefferson to flee Richmond, as well as set fires which burned the fledgling state capital and destroyed many colonial records. Just weeks earlier, on New Year's Eve, Wythe reportedly helped scare another raiding party back to their British ship, while hunting partridge.[41] Finally, four boatloads of neighbors attacked Hamilton St. George at his house on Hog Island on September 21, 1781, forcing him to flee to Chesterville, and ultimately New York and England. Chesterville sustained significant damage before Wythe evicted Mrs. St. George in order to move into the house with Elizabeth while French allies used their Williamsburg home.[42] During the Yorktown campaign which led to General Cornwallis' surrender, American and French troops camped at Williamsburg, and Count Rochambeau occupied the George Wythe house. On December 21, 1781 fire burned down the Governor's Palace and also destroyed a wing of the College which included Wythe's beloved library and physics instruments.[43]

Founding Father

Hurrying back to Virginia from Philadelphia, on June 23, 1776, Wythe began helping Virginia establish its new state government. Virginia's constitutional convention had begun months earlier (and had voted on May 15 to instruct the its federal delegates to move a declaration of independence).[44] Despite his late arrival, Wythe served on a committee with George Mason which jointly designed the Seal of Virginia, inscribed with the motto Sic Semper Tyrannis, which remains in use today. The reverse side shows three Roman goddesses, Libertas surrounded by Ceres and Aeternitas.[45] Wythe's most noteworthy contributions in establishing the new state government began when he again returned from Philadelphia that winter. Wythe served on a committee with Thomas Jefferson and Edmund Pendleton to revise and codify its laws, and also helped establish the new state court system. Although few of their 100+ separate proposed bills were ever passed, some concepts such as religious freedom, public records access, and education became important concepts in the new republic, as did the concept of intermediate appellate courts.[46] When a fall incapacitated Pendleton, Jefferson and Wythe redrafted his portion (much to Pendleton's dismay). Wythe also replaced Pendleton as Speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates the following term (1777–1778).

Wythe also continued working to establish the new nation. In 1787, Wythe became one of Virginia's delegates to the Constitutional Convention. Fellow delegate William Pierce considered Wythe "one of the most learned legal Characters of the present age" and known for his "exemplary life," but "no great politician" because he had "too favorable opinion of Men."[47] In any event, Wythe, Alexander Hamilton and Charles Pinckney, served on the committee which established the Convention's rules and procedures. However, Wythe left Philadelphia in early June to tend to Elizabeth, who was dying. The following year, York County neighbors elected Wythe and John Blair to represent them at the Virginia Ratifying Convention. As Chairman of the Committee of the Whole, Wythe presided over oft-heated exchanges until the final day. Stepping down from the chair, Wythe spoke to urge ratification. Pendleton later wrote Wythe's "adherence to the Constitution" gave the margin for ratification, when otherwise would have proven "grave for the Union."[48]

Teacher

Wythe's teaching career began with his appointment in 1761 to the Board of Visitors of the College of William and Mary, and often both overlapped and drew upon his legal and judicial careers. During more than twenty years, Wythe taught many legal apprentices, as well as students at the college. Among the most famous were future presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe; future senators Henry Clay, Littleton Waller Tazewell and John Breckinridge; future Virginia judges St. George Tucker and Spencer Roane; future Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, John Marshall; and future Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, Bushrod Washington. Proficient in Latin and Greek, as well as known for his devotion to books and learning, Wythe initially taught students on a near-individual apprenticeship basis. Especially after Elizabeth's death in 1787, some private pupils boarded at Wythe's home and received daily instruction in classical languages, as well as political philosophy and law.[49] Of all these men, Wythe remained closest to Jefferson, with whom he worked and corresponded many times in the ensuing decades. In their friendship, together the two men read all sorts of other material, from English literary works, to political philosophy, to the ancient sages.

In 1779, Governor Jefferson appointed Wythe to the newly created Chair of Law and Police, making Wythe the first law professor in the United States.[50] As a law professor, Wythe introduced a lecture system based on the Commentaries published by William Blackstone, as well as Matthew Bacon's New Abridgement of the Law, and Acts of Virginia's Assembly. Wythe also developed experiential tools, including moot courts and mock legislative sessions, which tools are still used today.[51] However, apprenticeship remained the main mode of learning law in that era, followed by examination before several practicing lawyers. Thus, not only did Marshall and Monroe attend Wythe's lectures for a time, they also affiliated themselves with more experienced lawyers before being admitted to the bar. The college suspended classes during the later days of the revolutionary war, after which Wythe both taught in Williamsburg and performed his duties as judge (mostly in Richmond as the new capital) until the 1788–1789 term. Wythe then resigned from the college and announced that he planned to move to Richmond to concentrate on his judicial duties. Travel to the new capital for the four judicial sessions each year may have become onerous, many of Wythe's friends and colleagues had died or moved, and Williamsburg's intellectual and cultural life had also declined after the state capital moved upriver. Litigation involving professor Rev. John Bracken also distressed Wythe.[52]

In Richmond, Wythe continued his pursuit of knowledge, and even began learning Hebrew from Rabbi Seixas.[53] One of Wythe's last pupils, William Munford, called Wythe "one of the most remarkable men I ever knew" and particularly remembered Wythe's scholarly philosophy, "Don't skim it; read deeply, and ponder what you read; they begin to make lawyers now without the 'biginti annorum lucubrationes' (twenty years of reflection) of Lord Coke; they are mere skimmers of the law, and know little else."[54] St. George Tucker, his one time student and fellow judge, succeeded Wythe as the college's law professor, and published an annotated edition of Blackstone's work before also resigning in 1804 to succeed Edmund Pendleton on Virginia's Supreme Court of Appeals. In 1920, the college (now a university) established a law school, which it named after Wythe and Marshall.

Virginia judge

Although Wythe served as what would now be called a justice of the peace in Elizabeth City County during colonial times, his reputation as the "American Aristides"[55] derived from Wythe's judicial service performed after Virginia became a state, as well as from his scholarship discussed above. The oath Wythe drafted for its admiralty judges indicates his judicial philosophy, "You shall swear that ... you will do equal right to all manner of people, great and small, high and low, rich and poor, according to equity and good conscience, and the laws and usages of Virginia, without respect to persons. ... And, finally, in all things belonging to your said office, during your continuance therein you shall faithfully, justly and truly, according to the best of your skill and judgment, do equal and impartial justice, without fraud, favor or affection, or partiality."[56] Wythe also designed the Chancery Court seal to illustrate the punishment of the Persian judge Sisamnes, killed and skinned after taking a bribe.[57]

In 1777, Wythe became one of the three judges on the new High Court of Chancery. Administering equity and developing that branch of the law became his mission for the rest of his life.[58] Wythe was elected to serve as a federal judge on the Court of Appeals in Cases of Capture in 1780, but declined to serve.[59][60] Wythe particularly despised lawyers who protracted litigation at great cost to the parties, though to their own benefit, and even in his last days regretted the burden delays placed upon those seeking justice from his court.[61] In the judicial reorganization of 1788, Wythe became sole Judge of the Chancery Court of Virginia, refusing to be promoted with Edmund Pendleton to the Supreme Court of Appeals (now known as the Virginia Supreme Court). Both men refused offers from President George Washington of judgships on the new federal courts, although their colleague John Blair accepted an appointment to the United States Supreme Court.[62] In 1802, the legislature created two more territorial Chancery Courts, but Wythe remained in Richmond.[63]

In the 1782 Commonwealth v. Caton[64] opinion, Wythe upheld judicial review of legislative actions, in what became a predecessor to Justice Marshall's decision in Marbury v. Madison. After Virginia courts had convicted Caton and two other men of treason, they appealed to the legislature for pardons. The House of Delegates approved their pardon request, but the state Senate refused. Wythe decided that not only did the court have the right to review that pardon, the judiciary was obliged to "say to them, here is the limit of your authority; and hither, shall you go, but no further."[65] Pendleton and Blair agreed with this principle of judicial review, although on slightly different grounds. Nonetheless, after the decision, both legislative houses pardoned the men, sparing them execution.[66]

However, Chancellor Wythe's decisions were modified or overruled many times, particularly by the appeals court that his former student Spencer Roane joined in 1794. In 1795, Wythe published analyses of some of his cases and subsequent appellate decisions, and added a few more pamphlets later.[67] Although this publication offended Pendleton, he decided against replying in kind.[68] One of Wythe's most famous decisions (unpopular at the time), Page v. Pendleton, upheld the authority of the 1783 federal peace treaty with Great Britain which required debts to British merchants be paid under the contract terms, although Virginia had passed a law (used by Edmund Pendleton and other executors of the will of Speaker John Robinson discussed above) that allowed payment in depreciated paper currency.[69] In Roane v. Innes, Wythe upheld revolutionary war soldiers's pension claims, but was reversed.[70] Pendleton died in 1803, just before he could deliver an opinion attempting to reverse Wythe in Turpin v. Lockett, which dealt with the sale of the disestablished church's glebe lands, nominally at least to support the poor.[71]

Wythe and slavery

One scholar states, without extensive documentation, that the problem of slavery preoccupied Wythe in his last years.[72] In 1785, Jefferson assured English abolitionist Richard Price that Wythe's sentiments against slavery were unequivocal.[73] During the first two decades after the war, so many Virginians freed slaves that the percentage of free blacks in the state rose from less than 1 percent to nearly 10 percent by 1810.[74] However, this era also saw the development of increasingly harsh slave laws, particularly as slaveholders feared rebellions similar to the Haitian Revolution which began in 1791. Tensions increased in 1793 when 137 vessels bearing French refugees from Haiti (and their slaves) arrived in Richmond. John Marshall and other prominent citizens wrote Governor Henry Lee III about slave rebellion rumors, and white militia armed.[75] Also, invention of the cotton gin in 1794 made cotton production using slave labor particularly profitable in the lower south, and those planters imported slaves from Maryland and Virginia, especially when importing slaves from Africa and Britain's Caribbean colonies became illegal and difficult. In 1798, Virginian legislators forbad members of slave emancipation societies from serving on juries involving slave freedom suits, which probably affected Wythe as a judge in such cases, as well as led the Virginia Abolition Society to all but disappear in that year.[76] In 1800 Governor James Monroe called out troops that crushed the rebellion led by Gabriel Prosser near Richmond, and 35 slaves were executed.[77] Further rumors of slave insurrections led to alarms and executions, sometimes without judicial process, in 1802 and 1803. Also, in the legislative session that began in the spring of 1806, the year of Wythe's death, a law passed requiring freed slaves to leave the state within 12 months, although a later modification allowed local courts to allow certain manumitted slaves to remain.[78]

Move to Richmond and manumissions

When Elizabeth died on August 18, 1787, Wythe returned some slaves whom her father had bequeathed to Elizabeth to her remaining relatives. Wythe filed manumission papers for his long-time housemaid and cook Lydia Broadnax on August 20, 1787, two days after Elizabeth's death. Four years later, Lydia accompanied Wythe as he moved to Richmond, where he had previously commuted four times yearly to deal with Chancery Court business.[79] In addition, a young mixed-race youth, Michael Brown, born free in 1790, lived in Wythe's household.[80] By 1797 Broadnax owned her own home, where she and Brown lived, and took in boarders. Wythe had taken an interest in Brown, taught him Greek and shared his library with him.[81] On January 29, 1797, Wythe also freed Benjamin, another adult slave who continued to work as his servant in Richmond; Wythe also named Benjamin a beneficiary in his 1803 will, which also included money for Brown's continued education.[79]

Fawn M. Brodie, who linked Jefferson and Sally Hemings, suggested that Broadnax was Wythe's concubine and Brown was their son. Wythe's biographer Imogene Brown noted both Brown's last name and Broadnax's age made such unlikely. Philip D. Morgan notes that there had been no documented gossip about Wythe and Broadnax at the time, unlike the case of Jefferson and Hemings, covered by newspapers and in individuals' letters and diaries.[79]

Judicial decisions

Wythe for years followed Virginia precedent (including the 1768 case Blackwell v. Wilkinson[82]) as he adjudicated chancery cases treating slaves as property.[83] Slavery matters often went to chancery, because there were no remedies at law. Virginia slave laws also became more severe as Richmond's importance as a slave trading center for points further south continued to increase, and French planters from what became Haiti came to Virginia with thousands of slaves. Wythe authored two legal opinions that attempted to steer Virginia away from the slave-based legal and economic system that entrenched in the early 19th century.

Wythe and Pendleton both sat on the Chancery court bench which granted freedom to slaves in Pleasants v. Pleasants. However, that decision was appealed, and in 1799, after Virginia passed a law forbidding abolitionists from serving on juries in freedom suits, Wythe's decision was modified by the appellate court led by Pendleton and Roane. This case concerned a Quaker's 1771 will, which purported to free slaves before Wythe and Jefferson drafted the 1782 law which legalized manumission in Virginia. Robert Pleasants and some of his siblings had freed about 100 slaves as his late father had requested, after that became legal and they became 30, as the will specified. Robert Pleasants also lobbied extensively for manumission laws and founded the Virginia Abolition Society in 1790. John Marshall and John Warden represented the slaves seeking their freedom, and Pleasants as executor of his father's will, as they jointly sued the siblings who failed to obey the testamentary instruction.[76] Each justice on the Court of Appeals in 'Pleasants v. Pleasants,' 2 Call 338–339 (1799) agreed with Wythe that the will could be enforced and called the slaves free. However, none of the justices (all slaveholders) thought Wythe's grant of backpay proper, and they all also agreed that children borne to slave parents would not actually gain their freedom until they repaid their owners' expenses in raising them, which in the intervening decades became quite large. Thus, although John Pleasants died holding over 530 slaves, fewer than a quarter received their freedom.

In one of Wythe's last cases, Hudgins v. Wright[84] (1806), Wythe "singlehandedly tried to abolish slavery by judicial interpretation," according to Paul Finkelman.[85] Jackey Wright, a slave, sued Houlder Hudgins (who, incidentally, had purchased Chesterville from Wythe)[86] for freedom for herself and her two children. Jackey based her claim on her descent from American Indians, including a woman named Butterwood Nan.[87] Indians were considered free in Virginia by this time.[88] Wythe ruled in favor of Wright on two grounds. He examined the women and noted that all three generations of the family showed only Indian and white ancestry, and no evidence of African ancestry. Because Hudgins did not provide definite proof of Wright's descent from a slave mother (though he argued Wright's grandmother was Betty Mingo not Hannah), Wythe considered Wright and her children "presumptively free". Alternatively, Wythe held that "all men were presumptively free in Virginia in consequence of the 1776 Declaration of Rights." This was similar to a contemporary ruling in Brom and Bett vs. Ashley, which held that Massachusetts' constitution upheld freedom for all men.

When Hudgins appealed to the Virginia Supreme Court after Wythe's murder, all judges unanimously affirmed Wythe's decision allowing Wright freedom, but only on limited grounds. Wythe's former student St. George Tucker affirmed Wythe's ruling only on the particular and limited nature of Indian enslavement in the state. The other extensive opinion in the case was by Judge Spencer Roane, who contrasted the presumption of freedom for Indians, as well as condemned Hudgins for failing to introduce evidence of any black ancestry of those seeking their freedom. Thus, all the appellate judges held that the two-decades old Declaration of Rights did not apply to blacks. Although Tucker (a slaveholder) rejected this judicial route to freedom, he had written in favor of [emancipation] and continued to fight for emancipation in other political venues.[89]

Death scandal

By 1805, Wythe's sister's grandson, 17-year-old George Wythe Sweeney, had come to live with his elderly namesake. The following spring, Wythe realized Sweeney stole some of his books, probably to repay gambling debts and support a dissolute lifestyle.[90] Wythe also revised his will in early 1806 because Thomas Jefferson had agreed to educate the young mulatto,[91][92] although those new provisions would have no effect if Brown died before Sweeney, as happened.

On Pentecost Sunday, May 25, Wythe, Broadnax and Brown all became violently ill. Richmond's leading doctors, Wythe's old friend James McClurg, James McCaw and his personal physician William Foushee at first suspected cholera, dismissing Wythe's claims of being poisoned.[93] Two days later, Sweeney tried to cash a $100 check drawn on Wythe's account, which the bank found suspicious because Wythe's illness had become news throughout the city. The bank retrieved several earlier checks, which Wythe had previously denied signing. Gravely ill but still trying to work on legal matters, Wythe refused to post bail for Sweeney, who was jailed.[94] Upon hearing that Brown had died on June 1, Wythe signed a codicil to his will drafted by Edmund Randolph that disinherited George Sweeney in favor of Charles, Jane and Ann Sweeney. Wythe also told the doctors "cut me." Although McClurg often used bloodletting,[95] the doctors agreed that Wythe actually called for an autopsy after his death, which happened on June 8, 1806. Oddly, Houlder Hudgins served as administrator for at least two of the siblings, who soon became Wythe's heirs.[96]

Broadnax recovered (although she ultimately suffered the effects for the rest of her life, and received some support from Jefferson). Broadnax told many people that she had seen Sweeney put a powder in their morning coffee.[97] Other black witnesses saw Sweeney drop paper from the jail, which appeared to contain rat poison. However, both trial judges agreed that Virginia race laws prohibited blacks from testifying at the trial.

After Wythe died, Sweeney was charged with poisoning Wythe and Brown with arsenic. Prominent attorneys William Wirt and Edmund Randolph defended Sweeney. The prosecutor was Philip Norborne Nicholas, Randolph's son-in-law. Early on, the judges quashed the murder charge relating to Brown, because of his race. A jury acquitted Sweeney of Wythe's murder. Some attributed the verdict to the botched autopsy (which failed to use well-known tests for arsenic),[98] and equivocal testimony by the physicians.[99] Others blamed Virginia law, which since 1732 forbade testimony by black witnesses, whether free or enslaved. [100][101] In a separate trial for check forgery, Sweeney was convicted. However, that conviction was overruled on appeal based on a technicality in the forgery law that Wythe and Jefferson had drafted years earlier (recognizing the crime only against individual victims, not against corporations such as the bank).[102] Sweeney left for Tennessee. There, he reportedly was later convicted and jailed for stealing a horse. Afterward he disappeared in history.[103]

Wythe's funeral was the largest in state history until that time. Richmond businesses closed for the day, and thousands lined the funeral route. The service was conducted at the state capitol.[104] Wythe was buried at St. John's Church in Richmond.[105]

Legacy and honors

In 1790 Wythe received the honorary degree of LL.D. from the College of William & Mary.[106]

In his will, Wythe left his large book collection to Thomas Jefferson. This was part of the collection which Jefferson later sold to create the Library of Congress. Jefferson praised Wythe as "... my ancient master, my earliest and best friend, and to him I am indebted for first impressions which have [been] the most salutary on the course of my life."[107] However, Jefferson later refused an offer of Wythe's lecture notes and other legal papers, believing they should go instead to what became the Library of Virginia.[108] Last reported either in the possession of Spencer Roane (who burned many papers before his own death) or his ally Thomas Ritchie (publisher of the Richmond Enquirer), they were reported lost by the 1830s.[109]

Places associated with Wythe remain preserved today, and over the centuries other places have been named in his honor:

- Wythe's home in Williamsburg, Virginia stands next to Bruton Parish Church, of which Wythe was a vestryman.[110] His house was acquired by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in 1938. Today it is operated as a museum, the Wythe House.

- Several places in Virginia were named for him: Wythe County, Virginia, its county seat Wytheville; high schools in Wytheville and Richmond; an elementary school in Hampton; a section of US-301 named Wythe Street in Petersburg; and the Olde Wythe Neighborhood in Hampton.

- The Marshall-Wythe School of Law at the College of William and Mary in Virginia.

- George Wythe University in Salt Lake City, Utah.

- George Wythe Hotel in Wytheville.

- George Wythe Randolph, Jefferson's grandson who became the Secretary of War of the Confederate States of America.

- Wythe Avenue, a main east-west residential street in the city of Richmond, was named for him.

The actor William Bakewell played Wythe in the 1965 episode entitled "George Mason" of the NBC documentary series, Profiles in Courage, based on writings of John F. Kennedy. Laurence Naismith portrayed Mason, and Arthur Franz played James Madison.[111]

See also

- George Wythe House

- Founding Fathers of the United States

- List of members of the Virginia House of Burgesses

- Robert Carter III, another Virginian slave-owner who manumitted his slaves

- U.S. Constitution, nationalist organizer in Convention

Notes

- ↑ Robert M. Cover, Justice Accused: Antislavery and the Judicial Process, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1975, pp. 51–5

- ↑ usconstitution.net Notes on the Constitution, US Constitution

- ↑ Online site for Colonial Williamsburg

- ↑ Alonzo Thomas Dill, George Wythe, Teacher of Liberty (Williamsburg, 1979), 5

- ↑ Dill at p. 12 indirectly citing George Wythe Mumford.

- ↑ Dill, p. 10.

- ↑ Dill p. 3.

- ↑ Dill, pp. 12–5.

- ↑ Imogene Brown, American Aristides (New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press 1981) at pp. 38–9.

- ↑ Stanard, William G. and Mary Newton Stanard. The Virginia Colonial Register. Albany, NY: Joel Munsell's Sons Publishers, 1902. OCLC 253261475, Retrieved July 15, 2011. p. 133.

- ↑ Stanard, 1902, pp. 135, 137, 139, 140–46.

- ↑ Brown at pp. 47–8 argues that Wythe served as burgess from Elizabeth City Country during 1756, and the College of William and Mary in 1758, but Chiswell defeated Wythe for the Williamsburg seat and he also lost the Elizabeth City County election, according to Robert Bevier Kirtland, George Wythe: Lawyer, Revolutionary Judge, University of Michigan thesis 1983 (University microfilms available through ProQuest) at p. 89 (hence Kirtland), more difficult to find but presumably more polished even if still doublespaced is the book of the same title published in 1986 by Garland Publishing Inc. of New York.

- ↑ Stanard, 1902, pp. 146–54.

- ↑ Dill, p. 15.

- ↑ Stanard, pp. 154–170–179.

- ↑ Brown, p. 36, citing William Meade, Old Churches, Ministers and Families of Virginia (Vol. 1)(Philadelphia 1856) p. 238 and a eulogy by Parson Weems reprinted in R.D. Anderson, "Chancellor Wythe and Parson Weems," William and Mary Quarterly series 1, vol. 25 (July 1916) pp. 13–9.

- ↑ Brown pp. 75–9.

- ↑ Kirtland, p. 63.

- ↑ Kirtland, at pp. 6671.

- ↑ Kirtland at 73.

- ↑ Kirtland at p. 82.

- ↑ Kirtland at pp. 82–3.

- ↑ According to Kirtland at p. 84, since Routledge died intestate and without heirs, his estate ultimately became a substantial endowment for Hampden–Sydney College.

- ↑ Kirtland at p. 86, quoting Marcus Fabius and Marcus Curtius, "To Metriotes," Virginia Gazette (P&D), 12 September 1766.

- ↑ Brown at pp. 85–6.

- ↑ Brown at pp. 97–100. Wythe served as Fauquier's executor with Robert Carter III.

- ↑ Kirtland, pp. 95–6.

- ↑ Brown at pp. 100–01.

- ↑ Brown, p. 101 citing Griffith, Virginia House of Burgesses, p. 51.

- ↑ Brown at p. 101.

- ↑ Brown at pp. 102–03.

- ↑ Brown at p. 102–03.

- ↑ "Key to Trumbull's picture", AmericanRevolution.org

- ↑ Brown at p. 121.

- ↑ Dill, p. 1.

- ↑ Brown, pp. 114–16.

- ↑ Kirtland, p. 104.

- ↑ Brown, pp. 149–57.

- ↑ Brown at p. 144.

- ↑ Brown, pp. 93–4, 103–04, 143; Kirtland, p. 9.

- ↑ Brown at p. 228.

- ↑ Brown at p. 210.

- ↑ Brown at pp. 210–12; Kirtland at pp. 128–29.

- ↑ Kirtland p. 106; Brown p. 140–41.

- ↑ Kirtland pp. 107-108; Brown at p. 142. The other members, Richard Henry Lee and Robert Carter Nicholas, were not active in the design. For an explanation of the changed back motto, see Susan Dunn, Dominion of Memories: Jefferson, Madison & the Decline of Virginia (New York: Basic Books, 2007) p. 31.

- ↑ Kirtland at pp. 110–18; Brown at pp. 174–96. George Mason and Thomas Ludwell Lee, while also appointed to the committee, soon resigned, citing health problems and lack of formal legal training.

- ↑ Kirtland p. 5, citing William Pierce, "Character Sketches of Delegates to the Federal Convention" in Max Ferrand, The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 Vol. III p. 94. available at http://www.usconstitution.net/constframe.html

- ↑ Brown at p. 241 citing David J. Mays, "Address on the Occasion of the Unveiling of the Bust of George Wythe"(Richmond: National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the Commonwealth of Virginia, 1964) p. 8.

- ↑ Brown at p. 220.

- ↑ Courthouse History, U.S. District Court, Washington, DC

- ↑ Brown, at p. 203.

- ↑ Kirtland at pp. 155–58.

- ↑ Brown p. 88.

- ↑ Brown, p. 227 citing William and Mary Quarterly, series I, Vol. 6, pp. 182–83.

- ↑ Brown at p. 225, citing John Tyler to Thomas Jefferson, November 12, 1810.

- ↑ Thomas W. Strahan, Retainer from the Lord (Iowa, 1976) p. 34.

- ↑ John T. Noonan, Jr., Persons and Masks of Law (New York: Farrar Straus, 1976) p. 31.

- ↑ Kirtland pp. 172–88.

- ↑ Library of Congress, Journals, Vol. 16, 79.

- ↑ Library of Congress, Journals, Vol. 16, 254.

- ↑ Kirtland pp. 183, 187.

- ↑ Brown, pp. 254–57.

- ↑ Kirtland pp. 180–81.

- ↑ "Commonwealth v. Caton 1782". Virginia1774.org. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ↑ Stanard at p. 39 citing 4 Call pp. 7–8. Caton is not listed as a party in the microfilm of Wythe's critical volume.

- ↑ Brown at p. 249.

- ↑ Kirtland pp. 179–80. The 1954 University of Virginia microfilm of the rare volume contains very few pages, although the index refers to more than 150 pages. For example, although the first numbered pages, 20–21, refer to Carter Braxton paying hard money debts in depreciated currency, the single-page index lists two cases concerning Braxton, the opposing litigants being Gregory in that beginning on the missing p. 13 and Love in the opinion supposedly beginning at the missing p. 58.

- ↑ David J. Mays, Edmund Pendleton (Harvard University Press 1953) vol II, p. 296.

- ↑ Pendleton was a named party in six other matters, for which the critical microfilm pages are missing. In addition to Page (beginning at the missing p. 127), the parties opposing a Pendleton in criticized decisions were Hinde (missing p. 145), Hoomes (missing p. 4), Lomax (missing p. 90), Ross (missing p. 147) and Whiting (missing p. 94). The 1814 Supreme Court case in which Justice Marshall wrote the opinion, Alexander v. Pendleton, 12 U.S. 462 (1814), was filed in 1806 against Nathanial Pendleton.

- ↑ Judge Spencer Roane or a relative may have been the named party opposing Innes (as mentioned in the index as beginning on the missing p. 62 – and Innes could have been another former Wythe student and lawyer Harry Innes, who became Kentucky's first U.S. district judge). The index also mentions another matter involving a Roane opposing Hearne and his wife (which began on the missing p. 111). Pendleton's co-executor and fellow Judge Peter Lyons might be the party opposing Dandridge in another case, in an index entry concerning an opinion starting on the missing p. 30. The carryover opinion on p. 32 concerns mistreatment of slave mothers causing their children to die.

- ↑ Brown pp. 265–66. Roane wrote the 1804 opinion allowing the sale, though the degree to which he affirmed Wythe is unclear. 'Turpin v. Turpin' appears in the microfilmed index of Wythe's volume of criticized cases issued years earlier, as starting on the missing p. 22. Roane's opinion is discussed in Edwin J. Smith and William Edward Dodd, Spencer Roane (Randolph-Macon College: 1903) at pp. 14–5. available free at google books but not downloading properly on 12/29/12.

- ↑ Robert Cover, see note 1.

- ↑ Noonan at p. 33.

- ↑ Peter Kolchin, American Slavery, 1619–1977, New York: Hill and Wang, 1993, p. 73.

- ↑ Virginius Dabney, Richmond: The Story of a City (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, rev. ed. 1990) pp. 51–2. Six ships carrying between 500 and 1000 black Catholic refugees, some free and wealthy and some enslaved, arrived in Baltimore in July 1791 and/or June 1793 after unsuccessful stops in Charleston, South Carolina and Norfolk, Virginia. Successively led by Sulpician priests themselves fleeing the French Revolution, and later Redemptorists and Jesuits, these black Catholics worshipped in the basement of St. Mary's Seminary, then the basement chapel of St. Ignatius Church (renamed for St. Peter Claver) before eventually forming America's first black parish, St. Francis Xavier Church (Baltimore, Maryland) during the Civil War era. Josephite priests also became associated with the parish a decade later, and the parish also moved in 1932 and 1968. http://www.josephite.com/parish/md/sfx/page2.html http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=7563 These early Haitian refugees also founded the Oblate Sisters of Providence in 1828, which order continues its teaching mission. http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=5559

- 1 2 "Virginia Abolition Society". Richmondfriends.org. 2004-04-05. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ↑ Dabney pp. 52–7.

- ↑ Dabney at p. 60.

- 1 2 3 Philip D. Morgan, "Interracial Sex in the Chesapeake", in Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson: History, Memory and Civic Culture, Eds. J.E. Lewis and P.S. Onuf. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999, pp. 55–60.

- ↑ Bruce Chadwick, "The Mysterious Death of George Wythe", American History, on History.net, February 2009, pp. 36–41

- ↑ Rev. Charles A. Goodrich, "George Wythe", in Lives of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence, New York: William Reed & Co., 1856, pp. 364–72, accessed 6 April 2011

- ↑ Jefferson's Rep. 73, 77 (1768), where the General Court had rejected his arguments against treating slaves as property

- ↑ Noonan at pp. 46, 55–60.

- ↑ Vernellia R. Randall (2010-01-01). "Hudgins v. Wrights (1806)". Academic.udayton.edu. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ↑ Paul Finkelman, "Thomas Jefferson and Slavery: The Myth Goes On", The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 102, No. 2, April 1994, p. 211.

- ↑ Kirtland, pp. 164–67. Wythe sold Chesterville to Daniel Hylton in October 1792, which may have helped Wythe to move to Richmond. However, Hylton advertised the property for sale or exchange for property in New York, New Jersey or Philadelphia in 1795, and Wythe foreclosed on the property in 1800 and again became its owner by sheriffs sale in June 1801. The cause of the default is uncertain, for the records are thought destroyed by fire in April 1865. Wythe resold Chesterville to prominent landowner Houlder Hudgins of newly created but nearby Mathews County, Virginia via an Indenture dated December 6, 1802, in Elizabeth City County Deed and Will Book, no. 12, pp. 232–34. This Houlder Hudgins also became guardian for Charles and Jane Sweeney, and probably Anne Sweeney, as appears in an 1811 action for partition brought by John Cary and Anne Sweeney Cary after their marriage, in vi, Henrico County record order book no. 16, p. 223

- ↑ "Hudgins v. Wright Case Material", Digital Archive: Tucker-Coleman Papers, Swem Library, William and Mary, available online, accessed 16 December 2012.

- ↑ Ariela J. Gross (2008), What Blood Won't Tell: A History of Race on Trial in America, pp. 23–4 ISBN 978-0-674-03130-2

- ↑ Cover (1975/1984), Justice Accused, p. 54.

- ↑ Chadwick, Bruce, I am Murdered: George Wythe, Thomas Jefferson and the Killing that Shocked a New Nation (John Wiley and Sons, 2009) pp. 123–24.

- ↑ Daniel Berexa, The Murder of Founding Father George Wythe Tennessee Bar Journal December 21, 2010, available at http://www.tba.org/journal/the-murder-of-founding-father-george-wythe

- ↑ despite Jefferson questioning blacks' mental capacities in Notes on the State Of Virginia available at http://frank.msu.edu/~lnelson/Jefferson-Slavery.html

- ↑ Chadwick pp. 25–6.

- ↑ Chadwick p. 124.

- ↑ Chadwick p. 181.

- ↑ Kirtland, pp. 166–67 citing an 1811 petition for partition in Vi, Henrico County Court Order Book, No. 16, p. 223.

- ↑ "George Sweeney Trial: 1806". encyclopaedia.com. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ↑ Chadwick pp. 167–94.

- ↑ Chadwick pp. 195–215

- ↑ "George Sweeney Trial: 1806 – Sweeney Poisons Wythe And Is Tried For Murder – Coffee, Brown, Michael, and Pot – JRank Articles". Law.jrank.org. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ↑ Chadwick pp. 228–32.

- ↑ Chadwick pp. 233–34. The legislature soon corrected the statute.

- ↑ Chadwick pp. 238–49.

- ↑ Chadwick, Bruce. "The Mysterious Death of Judge George Wythe". Historynet.com. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ↑ George Wythe at Find a Grave

- ↑ Catalogue of the College of William and Mary in Virginia from its Foundation to the Present Time. Williamsburg, VA: College of William and Mary. 1859. p. 97.

- ↑ William & Mary Law School (1954-09-25). "William & Mary Law – George Wythe". Law.wm.edu. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ↑ Brown pp. 224–25.

- ↑ Brown, p. 226; Kirtland, pp. 279–81. However, in the 1950s, David J. Mays, with the help of many others, managed to locate other reportedly long lost papers of that era, which enabled him to write Edmund Pendleton's biography.

- ↑ Williamsburg site, supra

- ↑ ""George Mason" in Profiles in Courage, May 2, 1965". Internet Movie Data Base. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

External links

- Philosophy and Biography on Wythe, George Wythe College, website

- "Hudgins v. Wright Case Material", Digital Archive: Tucker-Coleman Papers, Swem Library, William and Mary, available online

- Rev. Charles A. Goodrich, "Biography of George Wythe", 1856, Colonial Hall Website

- Wythepedia: The George Wythe Encyclopedia, Wolf Law Library, College of William & Mary

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by James Cocke |

Mayor of Williamsburg, Virginia 1768–1769 |

Succeeded by James Blair, Jr. |