Gerontoformica

| Gerontoformica Temporal range: Late Albian to Early Cenomanian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Gerontoformica cretacica holotype | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamila: | incertae sedis |

| Genus: | †Gerontoformica Nel & Perrault, 2004 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

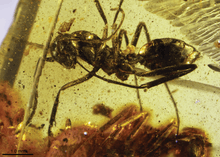

Gerontoformica is an extinct genus of stem-group ants. The genus contains thirteen described species known from Late Cretaceous fossils found in Asia and Europe. The species were described between 2004 and 2016, with a number of the species formerly being placed into the junior synonym genus Sphecomyrmodes.

History and classification

Gerontoformica is known from over thirty adult fossil specimens which are composed of complete adult female workers and queens.[1] The first fossil was discovered preserved as an inclusion in a transparent chunk of Charentese amber.[2] The amber is thought to have been formed from resins of the extinct Pinales tree family Cheirolepidiaceae and possibly from the living family Araucariaceae. Paleoecology of the ambers indicates the shore to mangrove type forests were of a subtropical to warm temperate climate, with occasional dry periods[3] The ambers are recovered from deposits exposed in quarries, road constructions, and beach exposures in the Charente-Maritime region of coastal France, notably at Archingeay.[2] Dating of the amber has been done through pollen analysis and it is generally accepted to be approximately 100 million years old.[3][4]

The majority of described fossils have been found and described from Burmese amber. The Asian specimens were recovered from unspecified deposits in the Hukawng Valley of Kachin State, Myanmar.[5] Burmese amber has been radiometrically dated using U-Pb isotopes, yielding an age of approximately 99 million years old, close to the boundary between the Aptian and Cenomanian.[5] The amber is suggested to have formed in a tropical environment around 5° north latitude and the resin to have been produced by either an Araucariaceae or Cupressaceae species tree.[6]

A team of French researchers headed by André Nel and G. Perrault published the 2004 type description of the new genus and species in the journal Geologica Acta. The genus name Gerontoformica was coined as a combination of the Greek word Geronto from the old age of the ant and Formica, a genus of ants. The genus had a single species the Charentese amber G. cretacica.[2]

In 2005 American paleoentomologists David Grimaldi and Michael Engel described a new Sphecomyrminae genus, Sphecomyrmodes based on a fossil found in Burmese amber. The name formed with the suffix -oides, meaning "with the form of" and the name Sphecomyrma, type genus of Sphecomyrminae. The new genus and single species S. orientalis were separated from Gerontoformica based on the 2004 type description which interpreted the G. cretacica antennae as having an elongated scape.[7] A second species, S. occidentalis, was added to Sphecomyrmodes in 2008 based on two specimens from Charentese amber.[8]

In a 2014 Plos One paper Phillip Barden and David Grimaldi, a series of nine new Burmese amber species were described and placed into Sphecomyrmodes: S. contegus, S. gracilis, S. magnus, S. pilosus, S. rubustus, S. rugosus, S. spiralis, S. subcuspis, and S. tendir. All the species were based on fossils in the private collection of James Zigras and loaned to the American Museum of Natural History for paleoentomologists to study.[5]

Barden and Grimaldi published a revision of Gerontoformica based on re-examination of the G. cretacica holotype, and identified Sphecomyrmodes as a junior synonym. They combined the eleven Sphecomyrmodes species into Gerontoformica and described a thirteenth species G. maraudera from Burmese amber.[1]

Behavior and ecology

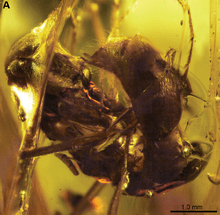

Several Burmese amber specimens were described in the 2016 Barden and Grimaldi paper that preserve groups of Gerontoformica workers in association. Specimen JZC Bu1814 contains a group of six G. spiralis worker caste adults in association with scolebythid wasp, a snail, the wings of two Parapolycentropus species mecopterans and a scydmaenid beetle. All the workers were entombed at the same time and there is indication that the resin flowed for a period after, severing the upper portions of the workers mesosomas and preserving the pieces apart from the rest of the ant.[1]

Amber specimen JZC Bu116 has a larger number of workers than JZC Bu1814, with a total of twelve workers belonging to two genera. Eleven of the ants are G. spiralis and the remaining worker is from the haidomyrmecine species Haidomyrmex zigrasi. The amber is broken into two portions and has been polished. The original amber piece that the specimen was from was likely larger, and the twelve ants are only a minimum number for what the grouping was. A large number of other arthropods are preserved in the amber with the ants, including several other hymenopteran families, a dermapteran, an orthopteran, seven dipterans, two arachnids, a myriapod, and a large blattodean. The blattodean is central to four of the ants, three G. sprialis and the H. zigrasi worker, suggesting the roach may have been either a potential food source, or one being actively foraged on. Due to a lack of orientation to the roach however, the possibility that the other eight G. sprialis were recruited to the prey blattodean is not clear.[1]

The third amber piece described was JZC Bu1645, which has three distinct flow layers preserved, dating from several hours to maybe days between flow events. Layer one is the smallest and top most, while layer three is the bottom most and largest. The presence of sand and humus particles along with a several entombed immature arthropods in the flows indicates the resin pooled on or near the forest floor. In total there are over twenty other arthropods and twenty-one ants preserved with the highest Gerontoformica diversity of the described amber specimens. At least three different species are present in the amber, G. contegus, G. orientalis, and G. robustus, and the workers are in three distinct groups in the layers. The layer one has a grouping of seven ants, layer two a grouping of three ants, and layer three a grouping of eleven ants. The largest group of ants show some directional orientation, with six of the workers facing essentially the same direction, but the other five show no direction.[1]

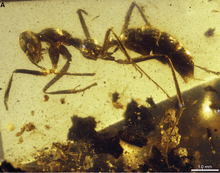

An additional amber fossil, JZC Bu1646, entombed two fighting Gerontoformica workers. The smaller G. tendir worker is gripping the right antennae between its mandibles. The larger G. spiralis worker is in turn in gripping the right fore leg protarsus between its left mandible and clypeus comb. Each ant is missing several antennae segments, and a bubble is exuding from the broken tip of the G. spiralis antennae. The bubble indicates the workers were alive while being entombed. Though fighting, neither of the workers has their metasoma curled under in an attempt to sting their foe, as is seen in modern ant fighting.[1]

The presence of large groups in single amber specimens is interpreted by Barden and Grimaldi as an indication that Gerontoformica species were social ants rather than solitary as the ancestral wasp groups were. While fighting between colonies and between different ant species is common, it is a behavior that is rare to non-existent in solitary aculeates hymenopterans. The specimen further suggests that Gerontoformica was a social genus.[1]

Descriptions

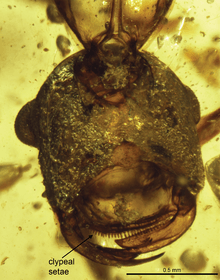

Gerontoformica is characterized by a row of peg like projections along the front edge of the clypeus, a feature not seen on other Cretaceous ant genera. The mandibles have a falcate shape, being curved to sickle shaped overall. The mandibles have a distinct tooth at the tip and a secondary tooth just back from the tip.[1]

G. contegus

The species is noted for having depressions, called scrobes, that the antennae recline into, a feature not seen in the other species. The total body length of the workers was between 5.05–5.19 mm (0.199–0.204 in), with a 1.21 mm (0.048 in) head and 1.65 mm (0.065 in) mesosoma. The head scrobes run from the upper edge of the clypeus to the lower edge of the compound eyes, and are the same width as the antenna scape. The ocelli are very reduced to not present, while the compound eyes are oval in outline and projecting out from the head in a frontal view. The antennae are composed of ten segments, with a total length of 3.52 mm (0.139 in). The clypeus has a convex front edge hosting about 22 thick setae, while the mandibles have scattered setae on the outside surfaces. On the mesosoma the metanotal spiracles and propodeal spiracles are distinctly projecting from the mesonotal surface. The gaster is marked with a distinct constriction on the upper surface between segments two and three, plus a sting is present at the gaster tip. The species name is a derivative of the Latin contago meaning "conceal or protect", in reference to the scrobes present on both the holotype and paratype.[5]

G. cretacica

Described from a single worker fossil in Chartense amber, the species has an estimated body length of 5.4 mm (0.21 in), though shrinking of the ant after entombment made accurate measurements difficult. The head has small indistinct compound eyes and no visible ocelli. The antennae are composed of 12 segments and the type description indicated the scape was notably longer than other Cretaceous genera.[2] However, in reexamination the scape was determined to be shorter than thought, and distortion of the fossil had caused the error with the type description.[1] The mandibles have the typical shape seen in the genus, overlapping slightly when closed, and with apical and subapical teeth. The clypeus sports approximately 32 denticles,[1] though the type description originally placed the denticles on the labrum.[2] While the type description mentioned the lack of a sting, the 2016 review of the fossil suggested the sting may have been missing prior to entombment.[1] The species name was derived from "Cretaceous", the age of the fossil.[2]

G. gracilis

The 6.62 mm (0.261 in) species was described from a pair of wingless females, assumed to be workers. There is a covering of tapered setae along the upper surface of the clypeus, and the front corners of the clypeus cover the bases of the mandibles. There is a row of over 20 denticles along the front edge of the clypeus.[5] Small ocelli are positioned just above and between the rear margins of the compound eyes. Due to the incomplete preservation of the head, the total length of the antennae could not be determined. Carinae formed from raised cuticle ridges run from the outside edges of the compound eyes to between the antennae bases. The mesosoma is notably elongated, being more than twice as long as high. The elongation of the mesopleuron results in a wide gap between the fore legs and the middle plus hind legs. While the metanotal spiracle is slightly raised from mesosoma on a turret like projection, the metapleural gland is placed in a slight depression in the mesosoma. The gaster is about half of the overall body length with a sting present in the holotype. The proportions of the head length and width are approximately even, as is seen in the species G. robustus, G. spiralis, and G. subcuspis. It is separated from them based on the frontal carinae and the proportional length of the mesosoma.[1] The species name "gracilis" is a reference to the slender elongated workers.[5]

The overall slender and elongated nature of this species is similar to the Burmese amber ant Myanmyrma gracilis, the modern crown group spider ants of Leptomyrmex and weaver ants of Oecophylla.[1]

G. magnus

The second largest of the species described, G. magnus workers average over 1.7 times the worker size in other Gerontoformica species, and only smaller than workers of G. maraudera.[1][5] The three described G. magnus workers range between 8.03–8.64 mm (0.316–0.340 in) long, with a generally teardrop shaped head capsulea and petioles that attach broadly to the mesosoma. The very large compound eyes have raised oval carinae surrounding them. Small ocelli are placed between the compound eyes on a flattened area of the head capsule. The area between the antennae is raised and carinae run from just under the antennae to just below the front edges of the compound eyes.[5] The antennae are formed of twelve segments totaling approximately 6.66 mm (0.262 in). There is a row of setae running above the upper margin of the clypeus, a second row running along the middle of the clypeus and row of notably elongated setae running along the front edge. Though obscured partially in the described fossils, there are over twenty five denticles running the length of the clypeus front edge. The mesosoma is blocky, being similar in length and width and with setae along the upper surface. Another patch of setae is present on the propodeum, sparse setae are found on the gaster and a group of tapered setae are clustered towards the end.[5] Based on the striking size of the workers, the species name "magnus" was chosen from the Latin meaning large.[5]

G. maraudera

The single described worker of G. maraudera is 8.67 mm (0.341 in), slightly larger than the workers of G. magnus.[1][5] The mandibles are distinct from other species in that they are not able to fully close against the clypeus due to their length. The lower front margin of the clypeus has a pointed projection on each side, and is smaller than other species, having a reduced look to it and being slightly covered in places. As typical for the genus, there is a row of denticles along the clypeus edge, numbering around 15, unlike the over 25 seen in G. magnus. The labial and maxillary palpomeres are visible, with the maxillary palpomeres intact and all 5 segments preserved, but the two segmented labial palpomeres damaged. At 6.07 mm (0.239 in), the antennae have twelve segments including the scape and pedicle. The mesosoma, petiole, and gaster all have sparse setae, as do the preserved area of all the legs. With a rounded node like appearance, the petiole has setae on the upper surface and a distinct projection from the underside. There is a notable constriction in the gaster, seen between the first and second segments that has a band like look.[1]

G. occidentalis

The two described workers of G occidentalis were originally entombed in the same small piece of Charentese amber, but the amber was cut into two smaller pieces to aid in study of the workers. The species is small, with an average body length of 3.84 mm (0.151 in).[8] The head is smooth with little to no carinae formed and no setae present except on the clypeus. The antennae are twelve segmented, the longest segment being the second funicular segment, while the pedicel is the shortest. As with the head, the mesosoma is smooth and lacking setae or textering of the upper surface. The legs have large coxae whose ventral surfaces have a coating of setae. On the forelegs, the basitarsomere has a curved upper section near the tibial joint and three elongated setae near the tip. Distinct and well developed antenna cleaners, called strigils, are preserved on the legs. The smooth mandibles, slightly shorter second funicular segment, and three setae on the basitarsomere distinguish G. occidentalis from other Gerontofromica.[8]

In the type description Perrichot and team noted that the name "occidentalis", meaning western, was chosen as a contrast to the first species of "Sphecomyrmodes", S. orientalis.[8]

G. orientalis

The head capsule of G. orientalis is smooth, lacking any major carinae or other structuring of the cuticle. There are scattered setae on the clypeus and on the exterior surfaces of the mandibles.[7] The head has a length of 1.23 mm (0.048 in) when the mandibles are closed. the pedicel is the shortest antenna segment, and funicular segment two is the longest. Segment two is also longer than that of G. occidentalis. The large coxae have setae on the undersides and have a slight flattening front to back. On the lower underside of the first tarsomere a comb of setae form a strigil. on the back sides of protarsomeres one, two, and three there are groups of three paired setae.[7] When described in 2005, the species was thought to be the first Sphecomyrmini species from Burmese amber, as such the specific epithet "orientalis", Latin for "of the east", was chosen.[7]

G. pilosus

As the species name indicates, G. pilosus has a very high amount of setae over the whole body of workers. The setae on the body reach lengths of nearly 0.25 mm (0.0098 in). The head has patches behind the ocelli, and on the sides of the head under the compound eyes. The twelve segmented antennae have very hairy scapes while the other segments only have sparse setae. The clypeus and mandibles have coatings of setae and the maxillary plus labial palps all have covering of very dense short setae. The mesosoma is elongated and has a narrow profile, with the pronotum elongated into a distinct neck. The spirical on the metanotum is raised from the surface of the metanotum on a turret like protrusion. The petiole has an overall node like appearance formed from a flat underside plus rounded dorsal surface having elongated setae. The gaster shows a distinct constriction on the upper surface between the first and second segments, which is narrow but very deep. The total body length is approximated to be 4.31 mm (0.170 in).[5]

G. robustus

The species is distinguished by a stout mesosoma that is about 30% as high as it is long. The species is noted for having the largest size variation between individual workers, with the body lengths of the three type specimens raging between 4.07–5.70 mm (0.160–0.224 in).[5] The size variation is an almost 40% difference between the smallest worker specimens and the largest.[1] The head is blocky, having rounded edges, an overall square shape, and a flattened area between and behind the two compound eyes. There are rounded rectangular carinae surrounding each of the oval eyes, and the ocelli are placed equidistantly from each other on the flat area of the head. There are scattered short setae on both gena and the clypeus. The lower margin of the clypeus has 20 denticles and a row of eight to ten longer setae that point toward the mandibles.[5] The mesosoma is smooth with little sculpturing other than the protruding spiracles and the deep distinct metanotal groove. Gasteral segment 1 has a distinct forward pointed hook like projection on the underside, while gasteral segment 4 has a fringe of setae along the back edge.[5] Given the thick body of the species, the name robustus, from the Latin for "strong", was chosen.[5]

G. rugosus

The single described worker of G. rugosus has distinct ridged texturing of the exoskeleton that runs along the mesosoma and metasoma. The rectangular head has raised cuticle between and behind the antennae, and extends down to the back margin of the clypeus. The compound eyes are smaller than seen in the other species, with an elongated outline, and placed closer to the articulation point with the body than to the clypeus. The lower edge of the clypeus has 32 denticles, and the front side edges obscure the mandible bases. The maxillary palps are visible in the fossil and show six segments present on each palp. In the other species of Gerontoformica the maxillary palps have only four segments where the palps are visible on specimens. The petiole has a round cylindrical shape rather than a node like shape seen in other species, and has the distinct longitudinal ribbing seen on the mesosoma. The details of the gaster are obscured by disarticulation and desiccation.[5]

G. spiralis

With a holotype and six paratypes, G. spiralis was described with the largest number of fossils of any Gerontoformica species. The species is noted for its similarity in appearance to G. orientalis, though the two are separated by several features and some of the features seen on G. spiralis are not visible on the G. orientalis holotype worker. Workers of G. spiralis are the smallest in the genus, ranging in body length between 4.22–5.11 mm (0.166–0.201 in). The head capsules are an inverted teardrop shape, with the compound eyes bulging from the head when viewed from the front. There are curved and spiral like carinae which start at the antennae sockets and curve around to the bottom margins of the compound eyes. The trapazoid shaped clypeus has raised areas on both edges and in a mound at its middle. Sparse setae are found on upper surface of the clypeus and approximately 25 denticles line the lower edge. The head is connected to the pronotum with a broad attachment area, while the petiole is a node shape. The metapleural gland forms an oval shaped opening that is located above the metacoxae.[5]

G. subcuspis

The head of G. subcuspis has a nearly square outline in frontal view, while from the side it shows an upside down raindrop outline expanding upwards from the mandibles. The compound eyes are surrounded by nearly circular carinae and additional carinae cure up from the bottom outer edges of the eyes to the antennae sockets. The antennae have a total length of approximately 3.34 mm (0.131 in), made of segments that are all the same length and smooth, lacking any large setae. On the clypeus there are numerous setae of differing lengths and a raised ridge runs along the middle of the sclerite. The upper edge has a wide notch while the lower edge has a convex rounded outline. The lower margin hosts about thirty denticles, mostly in a single rough, though in some sections two rows are present. On the pronotum the spiracle opening is located at the top of a small projection. The petiole has a node shaped outline, with a rounded upper outline and a front facing projection on the underside. The projection starts near the center of the petiole segment and slopes upward as it progressed to the front of the petiole, ending with a flat front face. The distinct projection is the inspiration for the species name subcuspis, which is a combination of the Latin prefix "sub-" for underside and "cuspis" meaning point.[5]

G. tendir

Due to darkening of the cuticle in the holotype fossil, finer details such as ocelli location and suture structuring were undetectable. The head has an elongated structure, being consistently taller than it is wide and the small compound eyes are placed near the midpoint between the clypeus and the rear edge.[1] At the back edge of the head the cuticle is raised into two small points. In both the G. tendir workers the middle of the clypeus is developed with a frontal lobe, and about twenty denticles are present on the front edge. The setae of the clypeus are confined to only the middle lobe, in contrast to the other described Gerontoformica species. The dark cuticle prevented description of the connection between head and mesosoma, but the lack of setae and smooth cuticle was observable. There are long setae and two spurs present on the mesotibia, with one spur pectinate, while the other is simple. The tarsomeres all have four setae near the apical ends, while the subapical tooth on each is smaller than in other species. Overall the holotype specimen has a body length of about 6.93 mm (0.273 in).[1]

Phylogeny

A phylogeny of stem group ants in relation to wasps and crown group ants was produced by Barden and Grimaldi in 2016. The phylogeny placed Gerontoformica as a stem group genus of Formicidae, and did not mention Sphecomyrmicinae as a subfamily, where the majority of the Gerontoformica species had been placed prior to the synonymization of Sphecomyrmodes into Gerontoformica.[1]

| Hymenoptera |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Barden, P.; Grimaldi, D.A. (2016). "Adaptive radiation in socially advanced stem-group ants from the Cretaceous". Current Biology. 26 (4): 515–521. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.12.060.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nel, A.; Perrault, G.; Perrichot, V.; Néradeau, D. (2004). "The oldest ant in the lower cretaceous amber of Charente-maritime (SW France) (Insecta: Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Geologica Acta. 2 (1): 23–29.

- 1 2 Peris, D.; Ruzzier, E.; Perrichot, V.; Delclòs, X. (2016). "Evolutionary and paleobiological implications of Coleoptera (Insecta) from Tethyan-influenced Cretaceous ambers". Geoscience Frontiers. doi:10.1016/j.gsf.2015.12.007.

- ↑ Perrichot, V.; Néraudeau, D.; Tafforeau, P. (2010). "Chapter 11: Charentese amber". In Penney, D. Biodiversity of Fossils in Amber from the Major World Deposits. Siri Scientific Press. pp. 192–207. ISBN 978-0-9558636-4-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Barden, P.; Grimaldi, D.A. (2014). "A Diverse Ant Fauna from the Mid-Cretaceous of Myanmar (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". PLoS ONE. 9 (4): e93627. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093627.

- ↑ McKellar, R. C.; Glasier, J. R. N.; Engel, M. S. (2013). "A new trap-jawed ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Haidomyrmecini) from Canadian Late Cretaceous amber". Canadian Entomologist. 145 (4): 454–465. doi:10.4039/tce.2013.23.

- 1 2 3 4 Engel, M.S.; Grimaldi, D.A. (2005). "Primitive New Ants in Cretaceous Amber from Myanmar, New Jersey, and Canada (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". American Museum Novitates. 3485: 1–24. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2005)485[0001:PNAICA]2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 3 4 Perrichot, V.; Nel, A.; Néraudeau, D.; Lacau, S.; Guyot, T. (2008). "New fossil ants in French Cretaceous amber (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)" (PDF). Naturwissenschaften. 95 (2): 91–97. doi:10.1007/s00114-007-0302-7. PMID 17828384.

External links

Media related to Gerontoformica at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gerontoformica at Wikimedia Commons