Giovanni Branca

| Giovanni Branca | |

|---|---|

| Born |

22 April 1571 Sant'Angelo in Lizzola, Italy |

| Died |

24 January 1645 (aged 73) Loreto |

| Residence | Loreto |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Fields | Engineer, Architect |

Giovanni Branca (22 April 1571 – 24 January 1645) was an Italian engineer and architect, chiefly remembered today for what some commentators have taken to be an early steam turbine.

Life

Branca was born on 22 April 1571 in Sant'Angelo in Lizzola. From 1616 Branca was employed at the Sacra Casa (Virgin’s Holy House) in Loreto. He was made a citizen of Rome in 1622. He died on 24 January 1645 in Loreto.[1]

Le Machine

Branca designed many different mechanical inventions, a collection of which he dedicated to Cenci, the governor of Loreto, Ancona. These were later published in book form at Rome in 1629, under the title Le machine.[2] The work contains 63 engravings with descriptions in Italian and Latin and was an example of the Theater of machines genre which had appeared in the 16th century, named after Jacques Besson's Theatrum Instrumentorum of 1571. However, where Besson's book had been beautifully illustrated with engravings, Branca's book was a small octavo volume illustrated with relatively poor quality woodcuts.

Unlike earlier authors, Branca did not claim to be the creator of many of the machines and in one instance is even uncertain over how the machine in question is supposed to work. In the words of historian Alex Keller, his machines "look like armchair inventions which seldom ever had any three-dimensional working counterparts".[3]

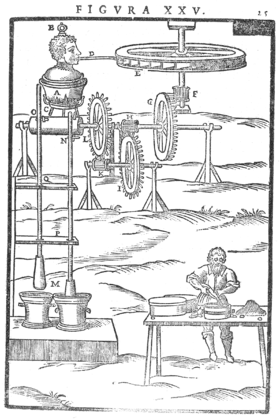

Branca's so-called steam engine appears as the 25th plate in Le Machine. It comprises a wheel with flat vanes like a paddlewheel, shown being rotated by steam produced in a closed vessel and directed at the vanes through a pipe (and hence would be more appropriately called a steam turbine). Branca suggested that it might be used for powering pestles and mortars, grinding machines, raising water, and sawing wood. It bears no relation to any later application of steam power and is not much of an advance over the aeolipile described by Hero of Alexandria in the first century AD.[4]

Manuale d’Architettura

Branca's Manuale d’Architettura, published in 1629, was a practical guide for planning and construction and is considered the first "pocket" architectural handbook. Branca's experience as an architect was due to his posting as superintendent of works of the Sacra Casa in Loreto, to which he was appointed by the Duke of Urbino.[5] Most of his architectural works are the detailed architectural renderings of Jacques Besson and Androuet du Cerceau. It was republished in 1772 by Leonardo de Vegni.[6]

Branca communicated with Benedetto Castelli and references his work in the last chapter of the Manuale, a chapter about rivers. Castelli, often considered to be the founder of the field of hydrodynamics, wrote to Branca urging him to defend himself against naïve or interested parties such as the Venetians who had rejected Castelli’s opinions as to why their lagoons were silting. On another occasion, Branca wrote to Castelli regarding a design for a nozzle for an inverted siphon to be installed in a fountain. Castelli also witnessed the ecclesiastical innocence of Le Machine for the inquisition.

Influence of Branca's work

It is unclear how influential Branca’s work was. But it was known that Robert Hooke owned a copy of Branca’s work.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ "Facetation / george goodall". web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 2006-10-18. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- ↑ Lardner, Dionysius (1840). The Steam Engine Explained and Illustrated. Taylor and Walton. p. 22.Full title:Le Machine volume nuovo, et di molto artificio da fare effetti maravigliosi tanto Spiritali quanto di Animale Operatione, arichito di bellissime figure. Del Sig. Giovanni Branco, Cittadino Romano. In Roma, 1629

- ↑ Keller, Alex; Ferguson, E. S.; Gnudi, M. T.; Ramelli, Agostino; Branca, Giovanni. "Renaissance theatres of machines". Technology and Culture. Johns Hopkins University Press. 19 (3): 495–508. doi:10.2307/3103380. JSTOR 3103380.

- ↑ Lardner, p.23

- ↑ Ticozzi, Stefano (1830). Dizionario degli architetti, scultori, pittori, intagliatori in rame ed in pietra, coniatori di medaglie, musaicisti, niellatori, intarsiatori d’ogni etá e d’ogni nazione' (Volume 1). Gaetano Schiepatti. p. 211.

- ↑ S. Ticozzi, p. 211

- ↑ McGee, Sarah (2000). Bernini’s Books. The Burlington Magazine. 142.1168: 442-448.