Giovanni Giolitti

| Giovanni Giolitti | |

|---|---|

| |

| 13th Prime Minister of Italy | |

|

In office June 15, 1920 – July 4, 1921 | |

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Preceded by | Francesco Saverio Nitti |

| Succeeded by | Ivanoe Bonomi |

|

In office March 30, 1911 – March 21, 1914 | |

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Preceded by | Luigi Luzzatti |

| Succeeded by | Antonio Salandra |

|

In office May 29, 1906 – December 11, 1909 | |

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Preceded by | Sidney Sonnino |

| Succeeded by | Sidney Sonnino |

|

In office November 3, 1903 – March 12, 1905 | |

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Preceded by | Giuseppe Zanardelli |

| Succeeded by | Tommaso Tittoni |

|

In office May 15, 1892 – December 15, 1893 | |

| Monarch | Umberto I |

| Preceded by | Marchese di Rudinì |

| Succeeded by | Francesco Crispi |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |

|

In office May 29, 1881 – July 17, 1928 | |

| Constituency | Piedmont |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

October 27, 1842 Mondovì, Kingdom of Sardinia |

| Died |

July 17, 1928 (aged 85) Cavour, Piedmont, Kingdom of Italy |

| Political party |

Historical Left (1882–1913) Liberal Union (1913–1922) Italian Liberal Party (1922–1926) |

| Alma mater | University of Turin |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Giovanni Giolitti (Italian pronunciation: [dʒoˈvanni dʒoˈlitti]; October 27, 1842 – July 17, 1928) was an Italian statesman. He was the Prime Minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921. He is the second-longest serving Prime Minister in Italian history, after Benito Mussolini.

Giolitti was a master in the political art of Trasformismo, the method of making a flexible, centrist coalition of government which isolated the extremes of the left and the right in Italian politics after the unification. Under his influence, the Italian Liberals did not develop as a structured party. They were, instead, a series of informal personal groupings with no formal links to political constituencies.[1] The period between the start of the 20th century and the start of World War I, when he was Prime Minister and Minister of the Interior from 1901 to 1914 with only brief interruptions, is often referred to as the Giolittian Era.[2][3]

A left-wing liberal,[2] with strong ethical concerns,[4] Giolitti's periods in office were notable for the passage of a wide range of progressive social reforms which improved the living standards of ordinary Italians, together with the enactment of several policies of government intervention.[3][5] Besides putting in place several tariffs, subsidies and government projects, Giolitti also nationalized the private telephone and railroad operators. Liberal proponents of free trade criticized the "Giolittian System", although Giolitti himself saw the development of the national economy as essential in the production of wealth.[6]

Early career

Giolitti was born at Mondovì (Piedmont). His father Giovenale Giolitti had been working in the avvocatura dei poveri, an office assisting poor citizens in both civil and criminal cases. He died in 1843, a year after Giovanni was born. The family moved in the home of his mother Enrichetta Plochiù in Turin. At sixteen he entered the University of Turin and earned a law degree in 1860.[7] Subsequently, he pursued a career in public administration. That choice prevented him from participating in the decisive battles of the Risorgimento (the unification of Italy), for which his temperament was not suited anyway, but this lack of military experience would be held against him as long as the Risorgimento generation was active in politics.[7][8]

After a rapid career in the financial administration he was, in 1882, appointed councillor of state. At the 1882 Italian general election he was elected to the Chamber of Deputies (the lower house of Parliament) for the Liberal Left.[8] As deputy he chiefly acquired prominence by attacks on Agostino Magliani, treasury minister in the cabinet of Agostino Depretis, and on 9 March 1889 was himself selected as treasury minister by Prime Minister Crispi. On the fall of the Antonio di Rudinì cabinet in May 1892, Giolitti, with the help of a court clique, succeeded to the premiership.

First term as Prime Minister

Giolitti's first term as Prime Minister (1892–1893) was marked by misfortune and misgovernment. The building crisis and the commercial rupture with France had impaired the situation of the state banks, of which one, the Banca Romana, had been further undermined by misadministration. The Banca Romana had loaned large sums to property developers but was left with huge liabilities when the real estate bubble collapsed in 1887.[9] Then Prime Minister Francesco Crispi and his Treasury Minister Giolitti knew of the 1889 government inspection report, but feared that publicity might undermine public confidence and suppressed the report.[10]

The Bank Act of August 1893 liquidated the Banca Romana and reformed the whole system of note issue, restricting the privilege to the new Banca d'Italia – mandated to liquidate the Banca Romana – and to the Banco di Napoli and the Banco di Sicilia, and providing for stricter state control.[10][11] The new law failed to effect an improvement. Moreover, he irritated public opinion by raising to senatorial rank the governor of the Banca Romana, Bernardo Tanlongo, whose irregular practices had become a byword, which would have given him immunity from prosecution.[12] The senate declined to admit Tanlongo, whom Giolitti, in consequence of an intervention in parliament upon the condition of the Banca Romana, was obliged to arrest and prosecute. During the prosecution Giolitti abused his position as premier to abstract documents bearing on the case.

Simultaneously a parliamentary commission of inquiry investigated the condition of the state banks. Its report, though acquitting Giolitti of personal dishonesty, proved disastrous to his political position, and the ensuing Banca Romana scandal obliged him to resign.[13] His fall left the finances of the state disorganized, the pensions fund depleted, diplomatic relations with France strained in consequence of the massacre of Italian workmen at Aigues-Mortes, and a state of revolt in the Lunigiana and by the Fasci Siciliani in Sicily, which he had proved impotent to suppress. Despite the heavy pressure from the King, the army and conservative circles in Rome, Giolitti neither treated strikes – which were not illegal – as a crime, nor dissolved the Fasci, nor authorised the use of firearms against popular demonstrations.[14] His policy was “to allow these economic struggles to resolve themselves through amelioration of the condition of the workers” and not to interfere in the process.[15]

Impeachment and comeback

After his resignation Giolitti was impeached for abuse of power as minister, but the Constitutional Court quashed the impeachment by denying the competence of the ordinary tribunals to judge ministerial acts. For several years he was compelled to play a passive part, having lost all credit. But by keeping in the background and giving public opinion time to forget his past, as well as by parliamentary intrigue, he gradually regained much of his former influence.

He made capital of the Socialist agitation and of the repression to which other statesmen resorted, and gave the agitators to understand that were he premier would remain neutral in labour conflicts. Thus he gained their favour, and on the fall of the Pelloux cabinet in 1900 he made his comeback after eight years, openly opposing the authoritarian new public safety laws.[16] Due to a left-ward shift in parliamentary liberalism at the general election in June, after the reactionary crisis of 1898-1900, he was to dominate Italian politics until World War I.[17] He became Minister of the Interior in the administration of Giuseppe Zanardelli, of which he was the real head.[5]

The Giolittian Era

His policy of never interfering in strikes and leaving even violent demonstrations undisturbed at first proved successful, but indiscipline and disorder grew to such a pitch that Zanardelli, already in bad health, resigned, and Giolitti succeeded him as Prime Minister in November 1903. Giolitti’s prominent role in the years from the start of the 20th century until 1914 is known as the Giolittian Era, in which Italy experienced an industrial expansion, the rise of organised labour and the emergence of an active Catholic political movement.[5]

The economic expansion was secured by monetary stability, moderate protectionism and government support of production. Foreign trade doubled between 1900 and 1910, wages rose, and the general standard of living went up.[18] Nevertheless, the period was also marked by social dislocations.[8] There was a sharp increase in the frequency and duration of industrial action, with major labour strikes in 1904, 1906 and 1908.[5] Emigration reached unprecedented levels between 1900 and 1914 and rapid industrialization of the North widened the socio-economic gap with the South. Giolitti was able to get parliamentary support wherever it was possible and from whoever were willing to cooperate with him, including socialist and Catholics, who had been excluded from government before. Although an anti-clerical he got the support of the catholic deputies repaying them by holding back a divorce bill and appointing some to influential positions.[8]

During his second and third tenure as Prime Minister (1903–1905 and 1906–1909), he courted the left and labour unions with social legislation, including subsidies for low-income housing, preferential government contracts for worker cooperatives, and old age and disability pensions.[5] However, he, too, had to resort to strong measures in repressing some serious disorders in various parts of Italy, and thus he lost the favour of the Socialists. In March 1905, feeling himself no longer secure, he resigned, indicating Fortis as his successor. When Sonnino became premier in February 1906, Giolitti did not openly oppose him, but his followers did. When Sonnino was defeated in May, Giolitti became Prime Minister once more (1906–1909).

Trasformismo

Giolitti was the first long-term Italian Prime Minister in many years because he mastered the political concept of trasformismo by manipulating, coercing and bribing officials to his side. In elections during Giolitti's government, voting fraud was common, and Giolitti helped improve voting only in well-off, more supportive areas, while attempting to isolate and intimidate poor areas where opposition was strong.[19] Many critics accused Giolitti of manipulating the elections, piling up majorities with the restricted suffrage at the time, using the prefects just as his contenders. However, he did refine the practice in the elections of 1904 and 1909 that gave the liberals secure majorities.[8]

Giolitti returned to office as Italian Prime Minister from 1911 to 1914. During this time, he bowed to nationalist pressure and fought the controversial Italo-Turkish War which made Libya an Italian colony. In 1912, Giolitti had the parliament approve an electoral reform bill that expanded the electorate from 3 million to 8.5 million voters – introducing near universal male suffrage – while commenting that first "teaching everyone to read and write" would have been a more reasonable route.[20] Considered his most daring political move, the reform probably hastened the end of the Giolittian Era because his followers controlled fewer seats after the elections of 1913.[8]

When the Pope lifted the ban on Catholic participation in politics in 1913, and the electorate was expanded, he collaborated with the Catholic Electoral Union, led by Ottorino Gentiloni in the Gentiloni pact. It directed Catholic voters to Giolitti supporters who agreed to favour the Church's position on such key issues as funding private Catholic schools, and blocking a law allowing divorce. Radicals and Socialist condemned the alliance, and brought down Giolitti's coalition in March 1914.[21]

World War I

After Gioilitti's resignation, the conservative Antonio Salandra was brought into the national cabinet as the choice of Giolitti himself, who still commanded the support of most Italian parliamentarians. However, Salandra soon fell out with Giolitti over the question of Italian participation in World War I. Giolitti opposed Italy's entry into the war on the grounds that Italy was militarily unprepared. At the outbreak of the war in August 1914, Salandra declared that Italy would not commit its troops, maintaining that the Triple Alliance had only a defensive stance and Austria-Hungary had been the aggressor. In reality, both Salandra and his ministers of Foreign Affairs, Antonino Paternò Castello, who was succeeded by Sidney Sonnino in November 1914, began to probe which side would grant the best reward for Italy's entrance in the war and to fulfil Italy’s irrendentist claims.[22]

On 26 April 1915, a secret pact, the Treaty of London or London Pact (Italian: Patto di Londra), was signed between the Triple Entente (the United Kingdom, France, and the Russian Empire) and the Kingdom of Italy. According to the pact, Italy was to leave the Triple Alliance and join the Triple Entente. Italy was to declare war against Germany and Austria-Hungary within a month in return for territorial concessions at the end of the war.[22] Giolitti was initially unaware of the treaty. His aim was to get concessions from Austria-Hungary to avoid war.[23]

While Giolitti supported neutrality, Salandra and Sonnino, supported intervention on the side of the Allies, and secured Italy's entrance into the war despite the opposition of the majority in parliament. On 3 May 1915, Italy officially revoked the Triple Alliance. In the following days Giolitti and the neutralist majority of the Parliament opposed declaring war, while nationalist crowds demonstrated in public areas for entering the war. On 13 May 1915, Salandra offered his resignation, but Giolitti, fearful of nationalist disorder that might break into open rebellion, declined to succeed him as prime minister and Salandra's resignation was not accepted. On 23 May 1915, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary.[24]

Last term as Prime Minister and the rise of Fascism

In the electoral campaign of 1919 he charged that an aggressive minority had dragged Italy into war against the will of the majority, putting him at odds with the growing movement of Fascists.[8] He became Prime Minister for the last time from 1920-1921 during Italy's "red years," when workers’ occupation of factories increased the fear of a communist takeover and led the political establishment to tolerate the rise of the fascists of Benito Mussolini. Giolitti enjoyed the support of the fascist squadristi and did not try to stop their forceful takeovers of city and regional government or their violence against their political opponents. His last term saw Italy relinquish control over most of the Albanian territories it gained after World War I, following prolonged combat against Albanian irregulars in Vlorë.

He called for new elections in May 1921 but the disappointing results forced him to step down. Still the head of the liberals, he did not resist the country’s drift towards fascism.[8] When Mussolini marched on Rome in October 1922, Giolitti was on vacation in France. He supported Mussolini's government initially – accepting and voting in favour of the controversial Acerbo Law[25] which guaranteed that a party obtaining at least 25 percent and the largest share of the votes would gain two-thirds of the seats in parliament. He shared the widespread hope that the fascists would become a more moderate and responsible party upon taking power, but withdrew his support in 1924, voting against the law that restricted press freedom.

Death and legacy

Powerless, he remained in Parliament until his death in Cavour, Piedmont, on July 17, 1928. According to his biographer Alexander De Grand, Giolitti was Italy's most notable prime minister after Cavour.[26] Like Cavour, Giolitti came from Piedmont, and like other leading Piedmontese politicians he combined a pragmatism with an Enlightenment faith in progress through material advancement. An able bureaucrat, he had little sympathy for the idealism that had inspired much of the Risorgimento. He tended to see discontent as rooted in frustrated self-interest and accordingly believed that most opponents had their price and could be transformed eventually into allies.[17]

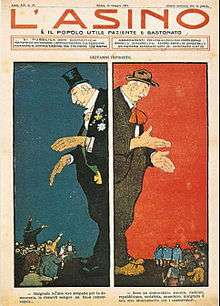

The primary objective of Giolittian politics was to govern from the center with slight and well controlled fluctuations, now in a conservative direction, then in a progressive one, trying to preserve the institutions and the existing social order.[26] Critics from the Right considered him a socialist due to the courting of socialist votes in parliament in exchange for political favours, while critics from the Left called him ministro della malavita (minister of the underworld) – a term coined by the historian Gaetano Salvemini – accusing him of winning elections with the support of criminals.[5][26]

He stands out as one of the major liberal reformers of late 19th- and early 20th-century Europe alongside Georges Clemenceau and David Lloyd George. He was a staunch adherent of 19th-century elitist liberalism trying to navigate the new tide of mass politics. A lifelong bureaucrat aloof from the electorate, Giolitti introduced near universal male suffrage and tolerated labour strikes. Rather than reform the state as a concession to populism, he sought to accommodate the emancipatory groups, first in his pursuit of coalitions with Socialist and Catholic movements, and finally, at the end of his political life, in a failed courtship with Fascism.[26]

Antonio Giolitti, the post-war leftist politician, was his grandson.

References

- ↑ Amoore, The Global Resistance Reader, p. 39

- 1 2 Barański & West, The Cambridge companion to modern Italian culture, p. 44

- 1 2 Killinger, The history of Italy, p. 127–28

- ↑ Coppa 1970

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sarti, Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present, pp. 46–48

- ↑ Coppa 1971

- 1 2 De Grand, The hunchback's tailor, p. 12

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sarti, Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present, pp. 313-14

- ↑ Alfredo Gigliobianco and Claire Giordano, Economic Theory and Banking Regulation: The Italian Case (1861-1930s), Quaderni di Storia Economica (Economic History Working Papers), Nr. 5, November 2010

- 1 2 Seton-Watson, Italy from liberalism to fascism, pp. 154-56

- ↑ Pohl & Freitag, Handbook on the history of European banks, p. 564

- ↑ Duggan, The Force of Destiny, p. 340

- ↑ Cabinet Forced To Resign; Italian Ministers Called "Thieves" by the People, The New York Times, November 25, 1893

- ↑ De Grand, The hunchback's tailor, pp. 47-48

- ↑ Seton-Watson, Italy from liberalism to fascism, pp. 162-63

- ↑ Clark, Modern Italy: 1871 to the present, p. 141-42

- 1 2 Duggan, The Force of Destiny, pp. 362-63

- ↑ Life World Library: Italy, by Herbert Kubly and the Editors of LIFE, 1961, p. 46

- ↑ Smith, Modern Italy; A Political History, p. 199

- ↑ De Grand, The hunchback's tailor, p. 138

- ↑ Frank J. Coppa. "Giolitti and the Gentiloni Pact between Myth and Reality," Catholic Historical Review (1967) 53#2 pp. 217-228 in JSTOR

- 1 2 Baker, Ray Stannard (1923). Woodrow Wilson and World Settlement, Volume I, Doubleday, Page and Company, pp. 52–55

- ↑ Clark, Modern Italy: 1871 to the present, p. 221-22

- ↑ Mack Smith, Modern Italy: A Political History, p. 262

- ↑ De Grand, The hunchback's tailor, p. 251

- 1 2 3 4 De Grand, The hunchback's tailor, pp. 4-5

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Giolitti, Giovanni". Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 31.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Giolitti, Giovanni". Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 31.

- Amoore, Louise (2005). The Global Resistance Reader, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-33584-1

- Barański, Zygmunt G. & Rebecca J. West (2001). The Cambridge companion to modern Italian culture, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-55034-3

- Clark, Martin (2008). Modern Italy: 1871 to the present, Harlow: Pearson Education, ISBN 1-4058-2352-6

- Coppa, Frank J. (1970). "Economic and Ethical Liberalism in Conflict: The extraordinary liberalism of Giovanni Giolitti,", Journal of Modern History (1970) 42#2 pp 191–215 in JSTOR

- Coppa, Frank J. (1967) "Giolitti and the Gentiloni Pact between Myth and Reality," Catholic Historical Review (1967) 53#2 pp. 217–228 in JSTOR

- Coppa, Frank J. (1971) Planning, Protectionism, and Politics in Liberal Italy: Economics and Politics in the Giolittian Age online edition

- De Grand, Alexander J. (2001). The hunchback's tailor: Giovanni Giolitti and liberal Italy from the challenge of mass politics to the rise of fascism, 1882-1922, Wesport/London: Praeger, ISBN 0-275-96874-X online edition

- Duggan, Christopher (2008). The Force of Destiny: A History of Italy Since 1796, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 0-618-35367-4

- Killinger, Charles L. (2002). The history of Italy, Westport (CT): Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-31483-7

- Mack Smith, Denis (1997). Modern Italy: A Political History, Ann Arbor (MI): Univ. of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-10895-4

- Pohl, Manfred & Sabine Freitag (European Association for Banking History) (1994). Handbook on the history of European banks, Aldershot: Edward Elgar Publishing, ISBN 1-85278-919-0

- Salomone, A. William, Italy in the Giolittian Era: Italian Democracy in the Making, 1900-1914 (1945)

- Sarti, Roland (2004). Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present, New York: Facts on File Inc., ISBN 0-81607-474-7

- Seton-Watson, Christopher (1967). Italy from liberalism to fascism, 1870-1925, New York: Taylor & Francis, 1967 ISBN 0-416-18940-7

- Smith, Dennis Mack (1997). Modern Italy; A Political History, Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, ISBN 0-472-10895-6

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Giovanni Giolitti. |

.svg.png)