Sima Yi's Liaodong campaign

| Sima Yi's Liaodong Campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the wars of the Three Kingdoms period | |||||||

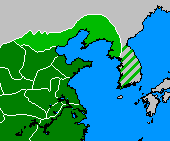

The territories of the Gongsun clan, shown in light green | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Cao Wei, Goguryeo | Gongsun clan of Liaodong | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Sima Yi, Guanqiu Jian, Hu Zun, Liu Xin, Xianyu Si, Goguryeo officials |

Gongsun Yuan †, Bei Yan, Yang Zuo | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Wei: 40,000[1] Goguryeo: Thousands[2] | Some tens of thousands, more than Wei's[3] | ||||||

Sima Yi's Liaodong campaign occurred in 238 during the Three Kingdoms period of Chinese history. Sima Yi, a general of the state of Cao Wei, led a force of 40,000 troops to attack the warlord Gongsun Yuan, whose clan had ruled independently from the central government for three generations in the northeastern territory of Liaodong (遼東; present-day eastern Liaoning). After a siege that lasted three months, Gongsun Yuan's headquarters fell to Sima Yi with assistance from Goguryeo (one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea), and many who served the Gongsun clan were massacred. In addition to eliminating Wei's rival in the northeast, the acquisition of Liaodong as a result of the successful campaign allowed Wei contact with the non-Han peoples of Manchuria, the Korean Peninsula, and the Japanese archipelago. On the other hand, the war and the subsequent centralization policies lessened the Chinese grip on the territory, which permitted a number of non-Han states to form in the area in later centuries.

Background

Liaodong commandery of You Province, part of present-day Manchuria, was situated at the northeastern fringe of Later Han China, surrounded by the Wuhuan and Xianbei nomads in the north and Goguryeo and Buyeo peoples in the east. In the autumn of 189, Gongsun Du, a native of Liaodong, was appointed as the Grand Administrator of Liaodong (遼東太守), and thus began the Gongsun family's rule in the region. Taking advantage of his distance from central China, Gongsun Du stayed away from the chaos which accompanied the effective end of Han Dynasty rule, expanded his territories to include the commanderies of Lelang and Xuantu, and eventually proclaimed himself as Marquis of Liaodong (遼東侯).[4] His son Gongsun Kang, who succeeded him in 204, created the Daifang Commandery and maintained the autonomy of Liaodong by aligning himself with the warlord Cao Cao.[5] Gongsun Kang died some time around the abdication of Emperor Xian of Han to Cao Pi, son of Cao Cao, and Gongsun Kang's brother Gongsun Gong became the new ruler of Liaodong. Gongsun Gong was described as incompetent and inept, and he was soon overthrown and imprisoned by Gongsun Kang's second son Gongsun Yuan in 228.[6]

Soon after Gongsun Yuan came to power in Liaodong, China was, for the most part, split into three: Cao Wei in the north, Shu Han in the southwest, and Eastern Wu in the southeast. Of these, Liaodong's chief concern was its immediate neighbour Cao Wei, who had once contemplated an invasion of Liaodong in response to Gongsun Yuan's coup.[6] In this situation, the Eastern Wu lord Sun Quan attempted to win Gongsun Yuan's allegiance in order to establish two fronts of attack against Cao Wei, and several embassies made their way from Wu to Liaodong by taking the difficult journey across the Yellow Sea. Cao Wei eventually got wind of the embassies and made one successful interception in Chengshan (成山), at the tip of the Shandong peninsula, but Gongsun Yuan had already sided with Sun Quan.[7] Upon the confirmation of Gongsun Yuan's goodwill, an elated Sun Quan sent another embassy in 233 to bestow Gongsun Yuan the title of King of Yan (燕王) and various insignia to trade for warhorses. By then, however, Gongsun Yuan had changed his mind about allying himself with a distant state over the sea and making himself an enemy of a powerful neighbour. When the Wu embassy arrived, Gongsun Yuan seized the treasures, killed the leading ambassadors, and sent their heads and a portion of their goods to the Wei court to buy himself back to favour.[8] Some of the envoys from Wu somehow escaped the carnage and found a potential ally to the east of Liaodong — the state of Goguryeo.

Goguryeo had been an enemy of the Gongsun since the time of Gongsun Du, especially after Gongsun Kang meddled with the succession after King Gogukcheon died. Thus when the Wu ambassadors came to Goguryeo for refuge, the reigning King Dongcheon was happy to assist these new enemies of Liaodong. The king sent 25 men to escort the envoys back to Wu along with a tribute of sable and falcon skins, which encouraged Sun Quan to send an official mission to Goguryeo to further the two states' relations. Cao Wei did not want to see Wu regain a diplomatic foothold in the north, and established its own connections with Goguryeo through the Inspector of You Province (幽州刺史) Wang Xiong (王雄).[9] King Dongcheon presumably arrived at the same conclusion as Gongsun Yuan and switched his alignment from Wu to Wei — the Wu envoys to Goguryeo in 236 were executed and their heads sent to the new Inspector of You Province, Guanqiu Jian. For the moment, both Liaodong and Goguryeo were aligned with Wei while Wu's influence diminished.

Prelude

Although Gongsun Yuan was nominally a vassal of Cao Wei, his brief flirtation with Wu and brazen derogatory comments about Wei earned him a reputation as unreliable. From Wei's point of view, although the Xianbei insurrection by Kebineng had been put down recently, Liaodong's position as a buffer zone against barbarian invasions needed to be clarified.[10] Therefore, it was clearly unacceptable that its leader, Gongsun Yuan, was of questionable loyalty. In 237, Guanqiu Jian presented a plan to invade Liaodong to the Wei court and put his plan into action. With troops of You Province as well as Wuhuan and Xianbei auxiliaries, Guanqiu Jian crossed the Liao River east into Gongsun Yuan's territory and clashed with his enemy in Liaosui (遼隧; near present-day Haicheng, Liaoning). There the Wei forces suffered a defeat, and were forced to retreat due to the floods caused by the summer monsoon season.[11]

Having inflicted a disgrace on the imperial armies, Gongsun Yuan had gone too far to turn back. In a series of contradictory actions that bear the hallmark of panic, Gongsun Yuan memorialised the Wei court in hope of getting a pardon on one hand, while formally declaring independence on the other by assuming the title King of Yan. He also assigned an era name for his reign, "Succeeding Han" (紹漢). This was problematic for his peace efforts for two reasons: first, proclaiming era names was a practice usually reserved for emperors, showing his intention to claim the imperial position; secondly, the era name itself implied that Wei's succession of the Han Dynasty was somehow illegitimate. As king, he tried to entice the Xianbei into attacking Cao Wei by conferring the rank of chanyu to one of its chiefs, but the Xianbei had not recovered from the death of Kebineng: the chieftains were too preoccupied with internal disputes to launch a large-scale attack on Wei.[12]

In 238, the Wei court summoned the Grand Commandant (太尉) Sima Yi for another campaign against Gongsun Yuan. Previously, Sima Yi had been tasked with defending Wei's western borders from Shu Han's Northern Expeditions led by the Shu chancellor Zhuge Liang, so when the latter died in 234, the government of Wei became able to afford sending Sima Yi elsewhere.[1] In a court debate prior to the campaign, the Wei emperor Cao Rui decided that Sima Yi should lead 40,000 men for the invasion of Liaodong. Some counsellors thought the number was too many, but Cao Rui overruled them, saying: "In this expedition of 4,000 li, mobile troops must be employed, and we must exert our utmost. We should not mind the expense at all."[13] The emperor then asked Sima Yi for his assessment on Gongsun Yuan's possible reactions and how long the campaign should take, Sima Yi responded as thus:

To leave his walls behind and take to flight would be the best plan for Gongsun Yuan. To take his position in Liaodong and resist our large forces would be the next best. But if he stays in [the Liaodong capital] Xiangping (襄平; present-day Liaoyang) and defends it, he will be captured....Only a man of insight and wisdom is able to weigh his own and the enemy's relative strength, and so give up something beforehand. But this is not something Gongsun Yuan can do. On the contrary, he will think that our army, alone and on a long-distance expedition, cannot long keep it up. He is certain to offer resistance on the Liao River first and defend Xiangping afterwards....A hundred days for going, another hundred days for the attack, still another hundred days for coming back, and sixty days for rest; thus one year is sufficient.[14]

When Sima Yi set out from the Wei capital Luoyang, Cao Rui went to the city gates in person to bid him farewell. Sima Yi, leading 40,000 infantry and cavalry, was accompanied by sub-commanders such as Niu Jin and Hu Zun (胡遵).[15] He would later be joined by Guanqiu Jian's forces in You Province,[16] which included the Xianbei auxiliary led by Mohuba (莫護跋), ancestor of the Murong clan.[17]

Having heard of the new preparations made against him, Gongsun Yuan desperately dispatched an envoy to the Wu court to apologize for his betrayal in 233 and begged for help from Sun Quan. At first, Sun Quan was ready to kill the messenger, but he was persuaded by Yang Dao (羊衜) to make a display of force and possibly gain advantages if Sima Yi and Gongsun Yuan became deadlocked in war. Cao Rui became concerned about the Wu reinforcements, but the advisor Jiang Ji read through Sun Quan's intentions and cautioned Cao Rui that while Sun Quan would not risk a deep invasion, the Wu fleet would make a shallow incursion into Liaodong if Sima Yi does not defeat Gongsun Yuan quickly enough.[18]

The campaign

The Wei army led by Sima Yi reached the banks of the Liao River by June 238. and Gongsun Yuan responded by sending Bei Yan and Yang Zuo with the main Liaodong force to set camp at Liaosui, the site of Guanqiu Jian's defeat. There, the Liaodong encampment stretched some 20 li walled from north to south.[19] The Wei generals wanted to attack Liaosui, but Sima Yi reasoned that attacking the encampment would only wear themselves out; on the other hand, since the bulk of the Liaodong army was at Liaosui, Gongsun Yuan's headquarters at Xiangping would be comparatively empty and the Wei armies could take it with ease. Thus Sima Yi sent Hu Zun to make a sortie to the southeast, planting flags and banners as if the main thrust of the Wei army was in that direction.[20] Bei Yan and his men hastened to the south, where Hu Zun, having lured his enemy out, crossed the river and broke through Bei Yan's line.[21] Meanwhile, Sima Yi secretly led the main Wei army across the Liao River to the north. After he made the crossing, he burned the bridges and boats, made a long barricade along the river, then headed toward Xiangping.[22] Realizing the feint, Bei Yan and his men hastily withdrew their troops during the night and headed north to intercept Sima Yi's army. Bei Yan caught up with Sima Yi in Mount Shou (首山), a mountain west of Xiangping, where he was ordered to fight to the death by Gongsun Yuan. Sima Yi achieved a great victory there, and proceeded to lay siege to Xiangping.

Along with the month of July came the summer monsoons, which impeded Guanqiu Jian's campaign a year ago. Rain poured constantly for more than a month so that ships could sail the length of the flooded Liao River from its mouth at the Liaodong Bay up to the walls of Xiangping. With the water several feet high on level ground, Sima Yi was determined to maintain the siege despite the clamours of his officers who proposed changing camps. Sima Yi executed Zhang Jing (張靜), an officer who kept bringing up the issue, and the rest of the officers became silent. Because of the floods, the encirclement of Xiangping was by no means complete, and the defenders used the flood to their advantage to sail out to forage and pasture their animals. Sima Yi forbade his generals from pursuing the foragers and herders from Xiangping, saying:

Now, the rebels are numerous and we are few; the rebels are hungry and we are full. With flood and rain like this, we cannot employ our effort. Even if we take them, what is the use? Since I left the capital, I have not worried about the rebels attacking us, but have been afraid they might flee. Now, the rebels are almost at their extremity as regards supplies, and our encirclement of them is not yet complete. By plundering their cattle and horses or capturing their fuel-gatherers, we will be only compelling them to flee. War is an art of deception; we must be good at adapting ourselves to changing situations. Relying on their numerical superiority and helped by the rain, the rebels, hungry and distressed as they are, are not willing to give up. We must make a show of inability to put them at ease; to alarm them by taking petty advantages is not the plan at all.[23]

The officials back in the Wei court in Luoyang were also concerned about the floods and proposed recalling Sima Yi. The Wei emperor Cao Rui, being completely certain in Sima Yi's abilities, turned the proposal down. About this time, the Goguryeo king sent a noble (大加, taeka) and the Keeper of Records (主簿, jubu) of the Goguryeo court with several thousand men to aid Sima Yi.[24]

When the rain stopped and the floodwater got drained away, Sima Yi hastened to complete the encirclement of Xiangping. The siege of Xiangping carried on night and day, which utilized mining, hooked ladders, battering rams, and artificial mounds for siege towers and catapults to get higher vantage points.[17][25] The speed at which the siege was tightened caught the defenders off guard: since they had been obtaining supplies with such ease during the flood there apparently was not any real attempt to stockpile the goods inside Xiangping, and as a result famine and cannibalism broke out in the city. Many Liaodong generals, such as Yang Zuo, surrendered to Sima Yi during the siege.

On September 3, a comet was seen in the skies of Xiangping and was interpreted as an omen of destruction by those in the Liaodong camp. A frightened Gongsun Yuan sent his high ministers Wang Jian (王建) and Liu Fu (柳甫) to negotiate the terms of surrender, where he promised to present himself bound to Sima Yi once the siege was lifted. Sima Yi, wary of Gongsun Yuan's double-crossing past, executed the two, explaining his actions in a message to Gongsun Yuan that he desired nothing less than an unconditional surrender and "these two men were dotards who must have failed to convey your intentions; I have already put them to death on your behalf. If you still have anything to say, then send a younger man of intelligence and precision."[26] When Gongsun Yuan sent Wei Yan (衛演) for another round of talks, this time requesting he be allowed to send a hostage to the Wei court, Sima Yi dismissed the final messenger as a waste of time: "Now that you are not willing to come bound, you are determined to have death; there is no need of sending any hostage."[27] Apparently, Sima Yi's previous suggestion of further negotiations was nothing more than an act of malice that gave false hope to Gongsun Yuan while prolonging the siege and placing further strain on the supplies within the city.[28]

On September 29, the famished Xiangping fell to the Wei army. Gongsun Yuan and his son Gongsun Xiu (公孫脩), leading a few hundred horsemen, broke out of the encirclement and fled to the southeast. The main Wei army gave pursuit and killed both father and son on the Liang River (梁水; present-day Taizi River 太子河). Gongsun Yuan's head was cut off and sent to Luoyang for public display. A separate fleet, led by future Grand Administrators Liu Xin (劉昕) and Xianyu Si (鮮于嗣), had been sent to attack the Korean commanderies of Lelang and Daifang by sea, and in time, all of Gongsun Yuan's state of Liaodong were subjugated.[29]

Aftermath

Entering the city, Sima Yi assembled all who had served in Gongsun Yuan's military and government under two banners. Everyone who had held office in Gongsun Yuan's rebel regime, over 1,000 to 2,000 in number, were executed in a systematic purge. In addition, 7,000 people of age 15 and above who had served in Liaodong's army were put to death, their corpses heaped up to form a great mound meant to terrorize.[30] After the massacre, he pardoned the survivors, posthumously rehabilitated Lun Zhi and Jia Fan — two Liaodong ministers against making war with Wei — and freed the overthrown Gongsun Gong from jail.[31] Finally, he dismissed the soldiers over sixty years of age from the Wei army on grounds of compassion, numbering over a thousand men, and marched back with the army.[32]

Although he had gained 40,000 households and some 300,000 people for the state of Wei from this expedition,[33] Sima Yi did not encourage these frontier settlers to continue their livelihoods in the Chinese northeast and instead ordered that those families who wished to return to central China be allowed to do so. In April or May 239, a Wu fleet commanded by Sun Yi (孫怡) and Yang Dao defeated the Wei defenders in southern Liaodong, prompting the Wei court to evacuate the coastal population to Shandong, further accelerating the trend of depopulation in Liaodong. This happened around the same time as the Xianbei chieftain Mohuba was awarded merit for his participation in the campaign against Gongsun Yuan, and his people were allowed to settle and thrive in northern Liaodong. By the beginning of the Western Jin Dynasty (265-316), the number of Chinese households fell to just 5,400.[34] After the fall of Western Jin, control over Liaodong was passed onto Former Yan (337-370), which was founded by Mohuba's descendents, and then to Goguryeo. For several centuries Liaodong would be out of Chinese hands, partly due to the lack of Chinese presence there as a result of the policies that Sima Yi and the Wei court adopted for Liaodong after the fall of the Gongsun.[35]

In the meantime, the removal of the Gongsun regime cleared a barrier between central China and the peoples of the further east. As early as 239, a mission from the Wa people of Japan under Queen Himiko reached the Wei court for the first time.[36] Goguryeo soon found itself rid of a nuisance that was only to be replaced by a stronger neighbour, and provoked Wei's wrath when it raided Chinese settlements in Liaodong and Xuantu commanderies. The Goguryeo–Wei Wars of 244 followed, devastating Goguryeo, and from it the Chinese re-established friendly contact with the Buyeo.[37] These developments could only have happened after Sima Yi's conquest of Liaodong, which, in some sense, represented the first step in recovering Chinese influence in the further east at the time.[37]

Modern references

The Liaodong campaign is featured as a playable stage in the seventh installment of Koei's Dynasty Warriors video game series in the newly introduced Jin Dynasty story line.

Notes

- 1 2 Gardiner (1972B), p. 168

- ↑ Gardiner (1972B), p. 165

- ↑ Fang, pp. 573, 591 note 12.2

- ↑ Gardiner (1972A), pp. 64-77

- ↑ Gardiner (1972A), p. 91

- 1 2 Gardiner (1972B), p. 147

- ↑ Gardiner (1972B), pp. 151-152

- ↑ Gardiner (1972B), p. 154

- ↑ Gardiner (1972B), p. 162

- ↑ Gardiner (1972B), p. 149

- ↑ Gardiner (1972B), p. 166

- ↑ Gardiner (1972B), p. 167

- ↑ Fang, p. 569

- ↑ Fang, pp. 569-570

- ↑ Fang, p. 585 note 1

- ↑ Chen, 28.5

- 1 2 Gardiner (1972B), p. 169

- ↑ Fang, pp. 570-571

- ↑ Fang, pp. 572, 591 note 12.2. Although the Book of Jin described the encampment as stretching 60 to 70 li, Sima Guang followed the Records of Three Kingdoms description since he considered 70 li too long for an encampment.

- ↑ Fang, p. 572

- ↑ Gardiner (1972B), p. 168

- ↑ Fang, p. 592 note 13.4

- ↑ Fang, p. 573

- ↑ Gardiner (1972B), pp. 165, 169. The names of these leaders of the Goguryeo expeditionary force were not recorded.

- ↑ Fang, p. 574

- ↑ Gardiner (1972B), p. 171

- ↑ Fang, p. 577

- ↑ Gardiner (1972B), pp. 172, 195 note 94.

- ↑ Ikeuchi, pp. 87-88

- ↑ Gardiner (1972B), pp. 172, 195-196 note 97

- ↑ Fang, p. 575

- ↑ Fang, p. 598 note 22

- ↑ Fang, p. 597

- ↑ Gardiner (1972B), p. 173

- ↑ Gardiner (1972B), p. 174

- ↑ Gardiner (1972B), p. 175-176

- 1 2 Gardiner (1972B), p. 175

References

- Chen, Shou. Records of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguozhi).

- Fang, Achilles. The Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms (220-265): chapters 69-78 from the Tzǔ chih t'ung chien of Ssǔ-ma Kuang (1019-1086). Vol. I. edited by Glen W Baxter. Harvard-Yenching Institute 1952.

- Fang, Xuanling et al. Book of Jin (Jin Shu).

- Gardiner, K.H.J. "The Kung-sun Warlords of Liao-tung (189-238)". Papers on Far Eastern History 5 (Canberra, March 1972). 59-107.

- Gardiner, K.H.J. "The Kung-sun Warlords of Liao-tung (189-238) - Continued". Papers on Far Eastern History 6 (Canberra, September 1972). 141-201.

- Ikeuchi, Hiroshi. "A Study on Lo-lang and Tai-fang, Ancient Chinese prefectures in Korean Peninsula". Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko 5 (1930). 79-95.