Grandiose delusions

Grandiose delusions (GD) or delusions of grandeur are a subtype of delusion that occur in patients suffering from a wide range of psychiatric diseases, including two-thirds of patients in manic state of bipolar disorder, half of those with schizophrenia, patients with the grandiose subtype of delusional disorder, and a substantial portion of those with substance abuse disorders.[1][2] GDs are characterized by fantastical beliefs that one is famous, omnipotent, wealthy, or otherwise very powerful. The delusions are generally fantastic and typically have a religious, science fictional, or supernatural theme. There is a relative lack of research into GD, in contrast to persecutory delusions and auditory hallucinations. About 10% of healthy people experience grandiose thoughts but do not meet full criteria for a diagnosis of GD.[2]

Prevalence

Research suggests that the severity of the delusions of grandeur is directly related to a higher self-esteem in individuals and inversely related to any individual’s severity of depression and negative self-evaluations.[3] Lucas et al. found that there is no significant gender difference in the establishment of grandiose delusion. However, there is a claim that ‘the particular component of Grandiose delusion’ may be variable across both genders.[2] Also, it had been noted that the presence of GDs in people with at least grammar or high school education was greater than lesser educated persons. Similarly, the presence of grandiose delusions in individuals who are the eldest is greater than in individuals who are the youngest of their siblings.[4]

Symptoms

According to the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for delusional disorders, grandiose-type symptoms include grossly exaggerated beliefs of:

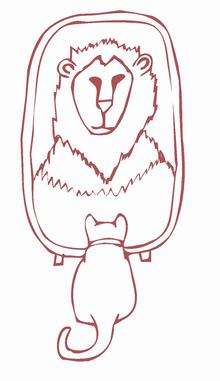

For example, a patient who has fictitious beliefs about his or her power or authority may believe himself or herself to be a ruling monarch who deserves to be treated like royalty.[7] There are substantial differences in the degree of grandiosity linked with grandiose delusions in different patients. Some patients believe they are God, the Queen of England, a president's son, a famous rock star, and so on. Others are not as expansive and think they are skilled sports-persons or great inventors.[8]

Expansive delusions

Expansive delusions may be maintained by auditory hallucinations, which advise the patient that they are significant, or confabulations, when, for example, the patient gives a thorough description of their coronation or marriage to the king. Grandiose and expansive delusions may also be part of fantastic hallucinosis in which all forms of hallucinations occur.[8]

Positive functions

Grandiose delusions frequently serve a very positive function for the person by sustaining or increasing their self-esteem. As a result, it is important to consider what the consequences of removing the grandiose delusion are on self-esteem when trying to modify the grandiose delusion in therapy.[5] In many instances of grandiosity it is suitable to go for a fractional rather than a total modification, which permits those elements of the delusion that are central for self-esteem to be preserved. For example, a woman who believes she is a senior secret service agent gains a great sense of self-esteem and purpose from this belief, thus until this sense of self-esteem can be provided from elsewhere, it is best not to attempt modification.[5]

Causes of delusion

There are two alternate causes for developing grandiose delusions:[9]

- Delusion-as-defense: defense of the mind against lower self-esteem and depression.

- Emotion-consistent: result of exaggerated emotions.

Epidemiology

In researching over 1000 individuals of vast range of backgrounds, Stompe and colleagues (2006) found that grandiosity remains as the second most common delusion after persecutory delusions.[2] A variation in the occurrence of grandiosity delusions in schizophrenic patients across cultures has also been observed.[10][11] In research done by Appelbaum et al. it has been found that GDs appeared more commonly in patients with bipolar disorder (59%) than in patients with schizophrenia (49%), followed by presence in substance misuse disorder patients (30%) and depressed patients (21%).[2]

A relationship has been claimed between the age of onset of bipolar disorder and the occurrence of GDs. According to Carlson et al. (2000), grandiose delusions appeared in 74% of the patients who were 21 or younger at the time of the onset, while they occurred only in 40% of individuals 30 years or older at the time of the onset.[2]

Diagnosis

Patients with a wide range of mental disorders which disturb brain function experience different kinds of delusions, including grandiose delusions.[12] Grandiose delusions usually occur in patients with syndromes associated with secondary mania, such as Huntington's disease,[13] Parkinson's disease,[14] and Wilson's disease.[15] Secondary mania has also been caused by substances such as levodopa and isoniazid which modify the monoaminergic neurotransmitter function.[16] Vitamin B12 deficiency,[17] uremia,[18] hyperthyroidism[19] as well as the carcinoid syndrome[20] have been found to cause secondary mania, and thus grandiose delusions.

In diagnosing delusions, the MacArthur-Maudsley Assessment of Delusions Schedule is used to assess the patient.[21]

Comorbidity

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder distinguished by a loss of contact with reality and the occurrence of psychotic behaviors, including hallucinations and delusions (unreal beliefs which endure even when there is contrary evidence).[22] Delusions may include the false and constant idea that the person is being followed or poisoned, or that the person’s thoughts are being broadcast for others to listen to. Delusions in schizophrenia often develop as a response to the individual attempting to explain their hallucinations.[22] Patients who experience recurrent auditory hallucinations can develop the delusion that other people are scheming against them and are dishonest when they say they do not hear the voices that the delusioned person believes that he or she hears.[22]

Specifically, grandiose delusions are frequently found predominantly in paranoid schizophrenia, in which a person has an extremely exaggerated sense of his or her significance, personality, knowledge, or authority. For example, the person may possibly declare to own IBM and kindly offer to write a hospital staff member a check for $5 million if they would only help them escape from the hospital.[23] Other common grandiose delusions in schizophrenia include religious delusions such as the belief that one is Jesus Christ.[24]

Bipolar disorder

Bipolar I disorder can lead to severe affective dysregulation, or mood states that sway from exceedingly low (depression) to exceptionally high (mania).[25] In hypomania or mania, some bipolar patients can suffer grandiose delusions. In its most severe manifestation, days without sleep or auditory and other hallucinations and uncontrollable racing thoughts can reinforce these delusions. In mania, this illness not only affects emotions but can also lead to impulsivity and disorganized thinking which can be harnessed to increase their sense of grandiosity. Protecting this delusion can also lead to extreme irritability, paranoia and fear. Sometimes their anxiety can be so over-blown that they believe others are jealous of them and, thus, are undermining their "extraordinary abilities," persecuting them or even scheming to seize what they already have.[26]

The vast majority of bipolar patients rarely experience delusions. Typically, when experiencing or displaying a stage of heightened excitability called mania, they can experience, joy, rage, a flattened state in which life has no meaning and sometimes even a mixed state of intense emotions which can cycle out of control along with thoughts or beliefs that are grandiose in nature. Some of these grandiose thoughts can be the expressed as strong beliefs that the patient is very rich or famous or has super-human abilities, or can even lead to severe suicidal ideations.[27] In the most severe form, in what was formerly labeled as megalomania, the bipolar patient may hear voices which support these grandiose beliefs. In their delusions, they can believe that they are, for example, a king, a creative genius, or can even exterminate the world's poverty because of their extreme generosity.[28]

Anatomical aspects

Grandiose delusions are frequently and almost certainly related to lesions of the frontal lobe. Temporal lobe lesions have been mainly reported in patients with delusions of persecution and of remorse, while frontal and frontotemporal involvement have been described in patients with grandiose delusions, Cotard’s syndrome, and delusional misidentification syndrome.[29]

Treatment

In patients suffering from schizophrenia, grandiose and religious delusions are found to be the least susceptible to cognitive behavioral interventions.[21] Cognitive behavioral intervention is a form of psychological therapy, initially used for depression,[30] but currently used for a variety of different mental disorders, in hope of providing relief from distress and disability.[31] During therapy, grandiose delusions were linked to patients' underlying beliefs by using inference chaining.[30][32] Some examples of interventions performed to improve the patient's state were focus on specific themes, clarification of neologisms, and thought linkage.[32] During thought linkage, the patient is asked repeatedly by the therapist to explain his/her jumps in thought from one subject to a completely different one.[32]

Patients suffering from mental disorders that experience grandiose delusions have been found to have a lower risk of having suicidal thoughts and attempts.[33]

See also

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Grandiose delusions |

References

- ↑ Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth edition Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) American Psychiatric Association (2000)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Knowles, R.; McCarthy-Jones S.; Rowse G. (2011). "Grandiose delusions: A review and theoretical integration of cognitive and affective perspectives". Clinical Psychology Review. 31 (4): 684–696. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.02.009. PMID 21482326.

- ↑ Smith, N.; et al. (2006). "Emotion and psychosis: Links between depression, self-esteem, negative schematic beliefs and delusions and hallucinations". Schizophrenia Research. 86 (1): 181–188. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.018. PMID 16857346.

- ↑ Lucas, C.J.; et al. (1962). "A social and clinical study of delusions in schizophrenia". The Journal of Mental Science. 108: 747–758. doi:10.1192/bjp.108.457.747.

- 1 2 3 Nelson, H.E. (2005). Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy with Delusions and Hallucinations: A Practice Manual. Nelson Thornes. p. 339. ISBN 9780748792566. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ↑ Sadock, B. J.; Sadock V.A. (2008). Kaplan and Sadock's Concise Textbook of Clinical Psychiatry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 752. ISBN 9780781787468.

- ↑ Davies, J.L.; Janosik E.H. (1991). Mental Health and Psychiatric Nursing: A Caring Approach. Boston, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 760. ISBN 9780867204421.

- 1 2 Casey, P.R.; Brendan K. (2007). Fish's Clinical Psychopathology: Signs and Symptoms in Psychiatry. UK: RCPsych Publications. p. 138. ISBN 9781904671329..

- ↑ Smith, N.; Freeman D.; Kuipers E. (2005). "Grandiose Delusions: An Experimental Investigation of the Delusion as Defense". Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 193 (7): 480–487. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000168235.60469.cc. PMID 15985843.

- ↑ Stompe, T.; et al. (2007). "Paranoid-hallucinatory syndromes in schizophrenia results of the international study on psychotic symptoms". World Cultural Psychiatry Review: 63–68.

- ↑ Suhail, K. (2003). "Phenomenology of delusions in Pakistani patients: effect of gender and social class". Psychopathology. 36: 195–199. doi:10.1159/000072789.

- ↑ Cummings, Jeffrey L. (1985). "Organic delusions: phenomenology, anatomical correlations and review" (PDF). The British Journal of Psychiatry. 146 (2): 184–197. doi:10.1192/bjp.146.2.184. PMID 3156653. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ↑ McHugh, P.R; Folstein, M.F (1975). "Psychiatric syndromes in Huntington's chorea". Psychiatric Aspectes of Neurological Disease.

- ↑ Bromberg, W. (1930). "Mental states in chronic encephalitis". Psychiatric Quarterly. 4: 537–566. doi:10.1007/bf01563408.

- ↑ Pandy, R.S.; Sreenivas, K.N.; Paith N.M.; Swamy H.S. (1981). "Dopamine beta-hydroxylase in a patient with Wilson's disease and mania". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 138 (12): 1628–1629. PMID 7304799.

- ↑ Lin, J-T Y.; Ziegler, D. (1976). "Psychiatric symptoms with initiation of carbidopa-levodopa treatment.". Neurology. 26: 679–700. doi:10.1212/wnl.26.7.699.

- ↑ Goggans, F.C. (1983). "A case of mania secondary to vitamin B12 deficiency.". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 141: 300–301.

- ↑ Cooper, A.T. (1967). "Hypomanic psychosis precipitated by hemodialysis.". Comprehensive Psychiatry. 8 (3): 168–172. doi:10.1016/s0010-440x(67)80020-8. PMID 6046067.

- ↑ Jefferson, J.W.; Marshall J.R. "Neuropsychiatric Features of Medical Disorders". New York: Plenum :Medical Book Company.

- ↑ Lehmann, J. (1966). "Mental disturbances followed by stupor in a patient with carcinoidosis.". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia. 42 (2): 153–161. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1966.tb01921.x. PMID 5958539.

- 1 2 Appelbaum, P.S.; Clark Robbins, P.; Roth, L. H. (1999). "Dimensional approach to delusions: Comparison across types and diagnoses". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 156 (12): 1938–1943. PMID 10588408.

- 1 2 3 Magill's Encyclopedia of Social Science: Psychology. California: Salem Press, Inc. 2003. pp. 718–719.

- ↑ Noll, R. (2009). The Encyclopedia of Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders. New York: Facts on File, Inc. p. 122. ISBN 9780816075089.

- ↑ Hunsley, J.; Mash E.J. (2008). A Guide to Assessment that Work. Oxford University Press. p. 676. ISBN 9780198042457.

- ↑ Barlow, D.H. (2007). Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders: A Step by Step Treatment Manual. New York: Guilford. p. 722. ISBN 9781606237656.

- ↑ Kantor, M. (2004). Understanding Paranoia: A Guide for Professionals, Families, and Sufferers. West Port: Greenwoord. p. 252. ISBN 9780275981525.

- ↑ Isaac, G. (2001). Bipolar Not Adhd: Unrecognized Epidemic of Manic Depressive Illness in Children. Lincoln: Writers Club Press. p. 184. ISBN 9781475906493.

- ↑ Fieve, R. R. (2009). Bipolar Breakthrough: The Essential Guide to Going Beyond Moodswings to Harness Your Highs, Escape the Cycles of Recurrent Depression, and Thrive with Bipolar II. Rodale. p. 288. ISBN 9781605296456.

- ↑ Tonkonogy, Joseph M.; Tonkonogiĭ T.M.; Puente A.E. (2009). Localization of Clinical Syndromes in Neuropsychology and Neuroscience. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company. p. 846. ISBN 9780826119681.

- 1 2 Beck, A.T.; Rush A.J.; Shaw B.F.; Emergy G (1979). "Cognitive Therapy of Depression". New York, NY. Guilford Press.

- ↑ Salkovskis, P.M. (1996). Frontiers of Cognitive Therapy. New York: Guillford.

- 1 2 3 Sensky, T.; et al. (2000). "A randomized controlled trial of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Persistent Symptoms in Schizophrenia resistant to medication". Archives of General Psychiatry. 57 (2): 165–172. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.57.2.165. PMID 10665619.

- ↑ Oquendo, M.A.; et al. (2000). "Suicidal behavior in bipolar mood disorder: clinical characteristics of attempters and nonattempters". Journal of Affect Disorders. 59: 107–117. doi:10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00129-9.