Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

.svg.png)

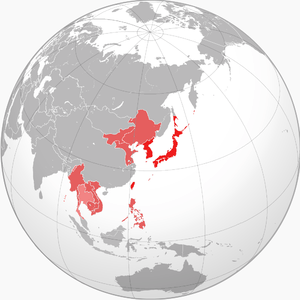

The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere (Japanese: 大東亞共榮圏 Hepburn: Dai-tō-a Kyōeiken) was an imperialist propaganda concept created and promulgated for occupied Asian populations during the first third of the Shōwa era by the government and military of the Empire of Japan. It extended greater than East Asia and promoted the cultural and economic unity of Northeast Asians, Southeast Asians, and Oceanians. It also declared the intention to create a self-sufficient "bloc of Asian nations led by the Japanese and free of Western powers". It was announced in a radio address entitled "The International Situation and Japan's Position" by Foreign Minister Hachirō Arita on June 29, 1940.[1]

An Investigation of Global Policy with the Yamato Race as Nucleus—a secret document completed in 1943 for high-ranking government use—laid out the superior position of Japan in the Greater Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, showing the subordination of other nations was part of explicit policy and not forced by the war.[2] It explicitly states the superiority of the Japanese over other Asian races and provides evidence that the Sphere was inherently hierarchical, including the Japanese Empire's true intention of domination over the Asian continent and Pacific Ocean.[3]

Development of concept

Similar to the term "Third Reich", which was a military exploitation of a non-military term proposed by Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, the phrase "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere" was proposed by Kiyoshi Miki, a Kyoto School analytic philosopher who was actually opposed to militarism.

An earlier, influential concept was the geographically smaller version called New Order in East Asia (東亜新秩序 Tōa Shin Chitsujo), which was announced by Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe on 22 December 1938 and was limited to Northeast Asia only.[4]

The original concept was an idealistic wish to "free" Asia from colonial powers, but soon, nationalists saw it as a way to gain resources to keep Japan a modern power, and militarists saw the same resources as raw materials for war.[5] Many Japanese nationalists were drawn to it as an ideal.[6] Many of them remained convinced, throughout the war, that the Sphere was idealistic, offering slogans in a newspaper competition, praising the sphere for constructive efforts and peace.[7]

Konoe planned the Sphere in 1940 in an attempt to create a Great East Asia, comprising Japan, Manchukuo, China, and parts of Southeast Asia, that would, according to imperial propaganda, establish a new international order seeking "co prosperity" for Asian countries which would share prosperity and peace, free from Western colonialism and domination.[8] Military goals of this expansion included naval operations in the Indian Ocean and the isolation of Australia.[9] This would enable the principle of hakkō ichiu.[10]

This was one of a number of slogans and concepts used in the justification of Japanese aggression in East Asia in the 1930s through the end of World War II. The term "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere" is remembered largely as a front for the Japanese control of occupied countries during World War II, in which puppet governments manipulated local populations and economies for the benefit of Imperial Japan.

To combat the protectionist dollar and sterling zones, Japanese economic planners called for a "yen bloc."[11] Japan's experiment with such financial imperialism encompassed both official and semi-official colonies.[12] In the period between 1895 (when Japan annexed Taiwan) and 1937 (the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War), monetary specialists in Tokyo directed and managed programs of coordinated monetary reforms in Taiwan, Korea, Manchuria, and the peripheral Japanese-controlled islands in the Pacific. These reforms aimed to foster a network of linked political and economic relationships. These efforts foundered in the eventual debacle of the Greater East-Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.[13]

History

The concept of a unified East Asia took form based on an Imperial Japanese Army concept that originated with General Hachirō Arita, an army ideologist who served as Minister for Foreign Affairs from 1936 to 1940. The Japanese Army said the new Japanese empire was an Asian equivalent of the Monroe Doctrine,[14] especially with the Roosevelt Corollary. The regions of Asia, it was argued, were as essential to Japan as Latin America was to the U.S.[15]

The Japanese Foreign Minister Yōsuke Matsuoka formally announced the idea of the Co-Prosperity Sphere on August 1, 1940, in a press interview,[10] but it had existed in other forms for many years. Leaders in Japan had long had an interest in the idea. The outbreak of World War II fighting in Europe had given the Japanese an opportunity to demand the withdrawal of support from China in the name of "Asia for Asiatics", with the European powers unable to effectively retaliate.[16] Many of the other nations within the boundaries of the sphere were under colonial rule and elements of their population were sympathetic to Japan (as in the case of Indonesia), occupied by Japan in the early phases of the war and reformed under puppet governments, or already under Japan's control at the outset (as in the case of Manchukuo). These factors helped make the formation of the sphere, while lacking any real authority or joint power, come together without much difficulty.

As part of its war drive, Japanese propaganda included phrases like "Asia for the Asiatics!" and talked about the perceived need to liberate Asian countries from imperialist powers.[17] The failure to win the Second Sino-Japanese War 1937-1941 (-1945) was blamed on British and American exploitation of Southeast Asian colonies, even though the Chinese received far more assistance from the Soviet Union.[18] In some cases local people welcomed Japanese troops when they invaded, driving out British, French, and other governments and military forces. In general, however, the subsequent pragmatism and brutality of the Japanese military, particularly in China, led to people of the occupied areas regarding the new Asian imperialists as much worse than the Western imperialists.[17] The Japanese government directed that local economies be managed strictly for the production of raw war materials for the Japanese; a cabinet member declared, "There are no restrictions. They are enemy possessions. We can take them, do anything we want."[19]

An Investigation of Global Policy with the Yamato Race as Nucleus — a secret document completed in 1943 for high-ranking government use — laid out that Japan, as the originators and strongest military power within the region, would naturally take the superior position within the Greater Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, with the other nations under Japan's umbrella of protection.[2][3]

China and other Asian nations, on their own, were regarded as too weak and lacking in unity to be treated as fully equal partners, and this in any case would not have been in Japan's self-interest.[20] The booklet Read This and the War is Won—for the Japanese army—presented colonialism as an oppressive group of colonists living in luxury by burdening Asians. Since racial ties of blood connected other Asians to the Japanese, and Asians had been weakened by colonialism, it was Japan's self-appointed role to "make men of them again" and liberate them from their western oppressors[21]

From the Japanese point of view, one common principal reason stood behind both forming the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere and initiating war with the Allies: Chinese markets. Japan wanted their "paramount relations" in regard to Chinese markets acknowledged by the U.S. government. The U.S., recognizing the abundance of potential wealth in these markets, refused to let the Japanese have an advantage in selling to China. In an attempt to give Japan a formal advantage over the Chinese markets, the Japanese Imperial regime first invaded China and later launched the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

According to Foreign Minister Shigenori Tōgō (in office 1941-1942 and 1945), should Japan be successful in creating this sphere, it would emerge as the leader of Eastern Asia, and the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere would be synonymous with the Japanese Empire.[8]

Greater East Asia Conference

The Greater East Asia Conference (大東亜会議 Dai tō-a kaigi) took place in Tokyo on 5–6 November 1943: Japan hosted the heads of state of various component members of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The conference was also referred to as the Tokyo Conference. The common language used by the delegates during the conference was English.[22]

The conference addressed few issues of any substance but was intended by the Japanese to illustrate the Empire of Japan's commitments to the Pan-Asianism ideal and to emphasize its role as the "liberator" of Asia from western colonialism.

The following dignitaries attended:

- Hideki Tojo, Prime Minister of Japan

- Zhang Jinghui, Prime Minister of Manchukuo

- Wang Jingwei, President of the Nationalist Government of Republic of China in Nanjing

- Ba Maw, Head of State, State of Burma

- Subhas Chandra Bose, Head of State of Provisional Government of Free India (Arzi Hukumat-e-Azad Hind)

- José P. Laurel, President of the Second Philippine Republic

- Prince Wan Waithayakon, envoy from the Kingdom of Thailand

Tojo greeted them with a speech praising the "spiritual essence" of Asia, as opposed to the "materialistic civilization" of the West.[23] Their meeting was characterized by praise of solidarity and condemnation of Western colonialism but without practical plans for either economic development or integration.[24]

The conference issued a Joint Declaration promoting economic and political cooperation against the Allied countries.[25]

Members of Sphere

Real members at dates formally formed the Sphere during maximal area of Japanese expansion:

-

.svg.png) Japan with governments-general

Japan with governments-general -

Manchukuo 27 September 1940 – August 1945

Manchukuo 27 September 1940 – August 1945 -

Mengjiang (Inner Mongolia) 27 September 1940 – 1945

Mengjiang (Inner Mongolia) 27 September 1940 – 1945 -

.svg.png) Reorganized National Government of China 30 March 1940 – 10 August 1945

Reorganized National Government of China 30 March 1940 – 10 August 1945 -

.svg.png) State of Burma 1 August 1943 – 27 March 1945

State of Burma 1 August 1943 – 27 March 1945 -

.svg.png) Republic of the Philippines: 14 October 1943 – 17 August 1945

Republic of the Philippines: 14 October 1943 – 17 August 1945 -

.svg.png) Empire of Vietnam 11 March 1945 — 23 August 1945

Empire of Vietnam 11 March 1945 — 23 August 1945 -

Kingdom of Kampuchea 9 March 1945 – 15 April 1945

Kingdom of Kampuchea 9 March 1945 – 15 April 1945 -

.svg.png) Kingdom of Laos 1944 – August 1945

Kingdom of Laos 1944 – August 1945 -

Azad Hind 21 October 1943 – 18 August 1945

Azad Hind 21 October 1943 – 18 August 1945 -

Kingdom of Thailand 21 December 1941–

Kingdom of Thailand 21 December 1941–

Imperial rule

The ideology of Japan's colonial empire, as it expanded dramatically during the war, contained two somewhat contradictory impulses. On the one hand, it preached the unity of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, a coalition of Asian races, directed by Japan, against the imperialism of Britain, France, the Netherlands, the United States, and European imperialism generally. This approach celebrated the spiritual values of the East in opposition to the crass materialism of the West.[26] In practice, however, the Japanese installed organizationally-minded bureaucrats and engineers to run their new empire, and they believed in ideals of efficiency, modernization, and engineering solutions to social problems. It was fascism based on technology, and rejected Western norms of democracy. After 1945, the engineers and bureaucrats took over, and turned the wartime techno-fascism into entrepreneurial management skills.[27]

Japan set up puppet regimes in Manchuria and China; they vanished at the end of the war. The Army operated ruthless governments in most of the conquered areas, but paid more favorable attention to the Dutch East Indies. The main goal was to obtain oil. The Dutch destroyed their oil wells but the Japanese reopened them. However most of the tankers taking oil to Japan were sunk by American submarines, so Japan's oil shortage became increasing acute. Japan sponsored an Indonesian nationalist movement under Sukarno.[28] Sukarno finally came to power in the late 1940s after several years of battling the Dutch.[29]

The Philippines

With a view of building up the economic base of the Co-Prosperity Sphere, the Japanese Army envisioned using the Philippine islands as a source of agricultural products needed by its industry. For example, Japan had a surplus of sugar from Taiwan, and a severe shortage of cotton, so they tried to grow cotton on sugar lands with disastrous results. They lacked the seeds, pesticides, and technical skills to grow cotton. Jobless farm workers flocked to the cities, where there was minimal relief and few jobs. The Japanese Army also tried using cane sugar for fuel, castor beans and copra for oil, derris for quinine, cotton for uniforms, and abaca (hemp) for rope. The plans were very difficult to implement in the face of limited skills, collapsed international markets, bad weather, and transportation shortages. The program was a failure that gave very little help to Japanese industry, and diverted resources needed for food production.[30] As Karnow reports, Filipinos "rapidly learned as well that 'co-prosperity' meant servitude to Japan's economic requirements."[31]

Living conditions were bad throughout the Philippines during the war. Transportation between the islands was difficult because of lack of fuel. Food was in very short supply, with sporadic famines and epidemic diseases that killed hundreds of thousands of people.[32][33] In October 1943, Japan declared the Philippines an independent republic. The Japanese-sponsored Second Philippine Republic headed by President José P. Laurel proved to be ineffective and unpopular as Japan maintained very tight controls.[34]

Failure

The Co-Prosperity Sphere collapsed with Japan's surrender to the Allies in August 1945. Although Japan succeeded in stimulating anti-Westernism in parts of Asia, the sphere never materialized into a unified Asia. Dr. Ba Maw, wartime President of Burma under the Japanese, blamed the Japanese military:

- "The militarists saw everything only in a Japanese perspective and, even worse, they insisted that all others dealing with them should do the same. For them there was only one way to do a thing, the Japanese way; only one goal and interest, the Japanese interest; only one destiny for the East Asian countries, to become so many Manchukuos or Koreas tied forever to Japan. These racial impositions... made any real understanding between the Japanese militarists and the people of our region virtually impossible."[35]

In other words, the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere operated not for the betterment of all the East Asia countries, but rather for Japan's own interests, and thus the Japanese failed to gather support in other East Asian countries. Nationalist movements did appear in these East Asian countries during this period and these nationalists did, to some extent, cooperate with the Japanese. However, Willard Elsbree, professor emeritus of political science at Ohio University, claims that the Japanese government and these nationalist leaders never developed "a real unity of interests between the two parties, [and] there was no overwhelming despair on the part of the Asians at Japan's defeat".[36]

The failure of Japan to understand the goals and interests of the other countries involved in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere led to a weak association of countries bound to Japan only in theory and not in spirit. Dr. Ba Maw argues that Japan could have engineered a very different outcome if the Japanese had only managed to act in accord with the declared aims of "Asia for the Asiatics". He argues that if Japan had proclaimed this maxim at the beginning of the war, and if the Japanese had actually acted on that idea,

- "No military defeat could then have robbed her of the trust and gratitude of half of Asia or even more, and that would have mattered a great deal in finding for her a new, great, and abiding place in a postwar world in which Asia was coming into her own."[37]

Propaganda efforts

Pamphlets were dropped by airplane on the Philippines, Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak, Singapore, and Indonesia, urging them to join this movement.[38] Mutual cultural societies were founded in all conquered nations to ingratiate with the natives and try to supplant English with Japanese as the commonly used language.[39] Multi-lingual pamphlets depicted many Asians marching or working together in happy unity, with the flags of all the nations and a map depicting the intended sphere.[40] Others proclaimed that they had given independent governments to the countries they occupied, a claim undermined by the lack of power given these puppet governments.[41]

In Thailand, a street was built to demonstrate it, to be filled with modern buildings and shops, but 9⁄10 of it consisted of false fronts.[42] A network of Japanese-sponsored film production, distribution, and exhibition companies extended across the Japanese Empire and was collectively referred to as the Greater East Asian Film Sphere. These film centers mass-produced shorts, newsreels, and feature films to encourage Japanese language acquisition as well as cooperation with Japanese colonial authorities.[43]

Projected territorial extent

Prior to the escalation of World War II to the Pacific and East Asia, the Japanese planners regarded it as self-evident that the conquests secured in Japan's earlier wars with Russia (South Sakhalin and Kwantung), Germany (Nanyo) and China (Manchuria) would be retained, as well as Korea (Chōsen), Taiwan (Formosa), the recently seized additional portions of China and occupied French Indochina.[44]

The Land Disposal Plan

A reasonably accurate indication as to the geographic dimensions of the Co-Prosperity Sphere are elaborated on in a Japanese wartime document prepared in December 1941 by the Research Department of the Imperial Ministry of War.[44] Known as the "Land Disposal Plan in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere" (大東亜共栄圏における土地処分案) it was put together with the consent of and according to the directions of the Minister of War (later Prime Minister) Hideki Tōjō. It assumed that the already established puppet governments of Manchukuo, Mengjiang, and the Wang Jingwei regime in Japanese-occupied China would continue to function in these areas.[44] Beyond these contemporary parts of Japan's sphere of influence it also envisaged the conquest of a vast range of territories covering virtually all of East Asia, the Pacific Ocean, and even sizable portions of the Western Hemisphere, including in locations as far removed from Japan as South America and the eastern Caribbean.[44]

Although the projected extension of the Co-Prosperity Sphere was extremely ambitious, the Japanese goal during the "Greater East Asia War" was not to acquire all the territory designated in the plan at once, but to prepare for a future decisive war some 20 years later by conquering the Asian colonies of the defeated European powers, as well as the Philippines from the United States.[45] When Tōjō spoke on the plan to the House of Peers he was vague about the long-term prospects, but insinuated that the Philippines and Burma might be allowed independence, although vital territories such as Hong Kong would remain under Japanese rule.[23]

The islands north of the equator that had been seized from Germany in World War I and which were assigned to Japan as C-Class Mandates, namely the Marianas, Carolines, Marshall Islands, and several others do not figure in this project.[44] They were the subject of earlier negotiations with the Germans and were expected to be officially ceded to Japan in return for economic and monetary compensations.[44]

The plan divided Japan's future empire into two different groups.[44] The first group of territories were expected to become either part of Japan or otherwise be under its direct administration. Second were those territories that would fall under the control of a number of tightly-controlled pro-Japanese vassal states based on the model of Manchukuo, as nominally "independent" members of the Greater East Asian alliance.

Parts of the plan depended on successful negotiations with Nazi Germany and a global victory by the Axis powers. After Germany and Italy declared war on the United States on December 11, 1941, Japan presented the Germans with a drafted military convention that would specifically delimit the Asian continent by a dividing line along the 70th meridian east longitude. This line, running southwards through the Ob River's Arctic estuary, southwards to just east of Khost in Afghanistan and heading into the Indian Ocean just west of Rajkot in India, would have split Germany's Lebensraum and Italy's spazio vitale territories to the west of it, and Japan's Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere and its other areas to the east of it.[46] The plan of the Third Reich for fortifying its own Lebensraum territory's eastern limits, beyond which the Co-Prosperity Sphere's northwestern frontier areas would exist in Northeast Asia, involved the creation of a "living wall" of Wehrbauer "soldier-peasant" communities defending it. However, it is unknown if the Axis powers ever formally negotiated a possible, complementary second demarcation line that would have divided the Western Hemisphere.

Japanese-governed

- Government-General of Formosa

- Hong Kong, the Philippines, Macau (to be purchased from Portugal), the Paracel Islands, and Hainan Island (to be purchased from the Chinese puppet regime). Contrary to its name it was not intended to include the island of Formosa (Taiwan)

- South Seas Government Office

- Guam, Nauru, Ocean Island, the Gilbert Islands and Wake Island.

- Melanesian Region Government-General or South Pacific Government-General

- British New Guinea, Australian New Guinea, the Admiralties, New Britain, New Ireland, the Solomon Islands, the Santa Cruz Archipelago, the Ellice Islands, the Fiji Islands, the New Hebrides, New Caledonia, the Loyalty Islands, and the Chesterfield Islands.

- Eastern Pacific Government-General

- Hawaii, Howland Island, Baker Island, the Phoenix Islands, the Rain Islands, the Marquesas and Tuamotu Islands, the Society Islands, the Cook and Austral Islands, all of the Samoan Islands, and Tonga. The possibility of re-establishing the defunct Kingdom of Hawaii was also considered, based on the model of Manchukuo.[47] Those favoring annexation of Hawaii (on the model of Karafuto) intended to use the local Japanese community, which had constituted 43% (c. 160,000) of Hawaii's population in the 1920s, as a leverage.[47] Hawaii was to become self-sufficient in food production, while the Big Five corporations of sugar and pineapple processing were to be broken up.[48] No decision was ever reached regarding whether Hawaii would be annexed to Japan, become a puppet kingdom, or be used as a bargaining chip for leverage against the US.[47]

- Australian Government-General

- All of Australia including Tasmania. Australia and New Zealand were to accommodate up to two million Japanese settlers.[47] However, there are indications that the Japanese were also looking for a separate peace with Australia, and a satellite rather than colony status similar to that of Burma and the Philippines.[47]

- New Zealand Government-General

- New Zealand North and South Islands, Macquarie Island, as well as the rest of the Southwest Pacific.

- Ceylon Government-General

- All of India below a line running approximately from Portuguese Goa to the coastline of the Bay of Bengal.

- Alaska Government-General

- The Alaska Territory, the Yukon Territory, the western portion of the Northwest Territories, Alberta, British Columbia, and Washington. There were also plans to make the American West Coast a semi-autonomous satellite state. This latter plan was not seriously considered; it depended upon a global victory of Axis forces.[47]

- Government-General of Central America

- Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, British Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, Maracaibo (western) portion of Venezuela, Ecuador, Cuba, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and the Bahamas. In addition, if either Mexico, Peru or Chile were to enter the war against Japan, substantial parts of these states would also be ceded to Japan. Events that transpired between May 22, 1942 when Mexico declared war on the Axis, through Peru's declaration of war on February 12, 1944 and concluding with Chile only declaring war on Japan by April 11, 1945 (as Nazi Germany was nearly defeated at that time) brought all three of these southeast Pacific Rim nations of the Western Hemisphere's Pacific coast into conflict with Japan by the war's end. The future of Trinidad, British Guiana and Suriname, and British and French possessions in the Leeward Islands at the hands of Imperial Japan were meant to be left open for negotiations with Nazi Germany had the Axis forces been victorious.

Asian puppet states

- Chinese Manchuria.

- Outer Mongolia territories west of Manchuria.

- Other parts of China occupied by Japan.

- East Indies Kingdom

- Dutch East Indies, British Borneo, and Christmas Islands, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and Portuguese Timor (to be purchased from Portugal).

- Burma proper, Assam (a province of the British Raj) and large part of Bengal.

- Pre-war Thailand, which was also expanded with portions of British Malaya, Burma, and French Indochina during the war, although this wasn't included in the original plan.

- Kingdom of Malaya

- Remainder of the Malay states.

- Cambodia and parts of French Cochinchina.

- Kingdom of Annam

Political parties and movements with Japanese support

- Azad Hind (Indian nationalist movement)

- Indian Independence League (Indian nationalist movement)

- Indonesian Nationalist Party (Indonesian nationalist movement)

- Kapisanan ng Paglilingkod sa Bagong Pilipinas (Philippine nationalist ruling party of Second Philippine Republic)

- Kesatuan Melayu Muda (Malayan nationalist movement)

- Khmer Issarak (Cambodian-Khmer nationalist group)

- Dobama Asiayone (We Burmans Association) (Burmese anti-British nationalist association)

See also

- Hachirō Arita: Army thinker who thought up the Greater East Asian concept

- Satō Nobuhiro: alleged founder of the Greater East Asia concept

- East Asia Development Board

- Ministry of Greater East Asia

- Greater East Asia Conference (November 1943)

- Jewish settlement in the Japanese Empire

- List of East Asian leaders in the Japanese sphere of influence (1931–1945)

- Axis power negotiations on the division of Asia during World War II

References

Citations

- ↑ William Theodore De Bary (2008), Sources of East Asian Tradition: The modern period, p. 622, ISBN 0-231-14323-0

- 1 2 John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p263-4 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- 1 2 Dower, John W. (1986). War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War, pp. 262-290.

- ↑ Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (2006), Asian security reassessed, pp. 48-49, 63, ISBN 981-230-400-2

- ↑ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 447 Random House New York 1970

- ↑ James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 494 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ↑ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 449 Random House New York 1970

- 1 2 Iriye, Akira. (1999). Pearl Harbor and the coming of the Pacific War: a Brief History with Documents and Essays, p. 6.

- ↑ Ugaki, Matome. (1991). Fading Victory: The Diary of Ugaki Matome, 1941-1945, p. __.

- 1 2 James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 470 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ↑ James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 460 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ↑ James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 461-2 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ↑ Vande Walle, Willy et al. The 'money doctors' from Japan: finance, imperialism, and the building of the Yen Bloc, 1894-1937 (abstract). FRIS/Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 2007-2010.

- ↑ Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II, p252-3 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York

- ↑ William L. O'Neill, A Democracy at War: America's Fight at Home and Abroad in World War II. Free Press, 1993, p. 53. ISBN 0-02-923678-9

- ↑ William L. O'Neill, A Democracy at War, p. 62.

- 1 2 Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II, p 248 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York

- ↑ James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 471 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ↑ James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 495 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ↑ Beasley, William G., The Rise of Modern Japan, p 79-80 ISBN 0-312-04077-6

- ↑ John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War p24-5 ISBN 0-394-50030-X

- ↑ Alan J. Levine (1995), The Pacific War:Japan versus the allies, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-275-95102-2

- 1 2 W. G. Beasley, The Rise of Modern Japan, p 204 ISBN 0-312-04077-6

- ↑ Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa to the Present, p211, ISBN 0-19-511060-9, OCLC 49704795

- ↑ World War II Database (WW2DB): "Greater East Asia Conference."

- ↑ Jon Davidann, "Citadels of Civilization: U.S. and Japanese Visions of World Order in the Interwar Period," in Richard Jensen, et al. eds., Trans-Pacific Relations: America, Europe, and Asia in the Twentieth Century (2003) pp 21-43

- ↑ Aaron Moore, Constructing East Asia: Technology, Ideology, and Empire in Japan's Wartime Era, 1931-1945 (2013) 226-27

- ↑ Laszlo Sluimers, "The Japanese military and Indonesian independence," Journal of Southeast Asian Studies (1996) 27#1 pp 19-36

- ↑ Bob Hering, Soekarno: Founding Father of Indonesia, 1901-1945 (2003)

- ↑ Francis K. Danquah, "Reports on Philippine Industrial Crops in World War II from Japan's English Language Press," Agricultural History (2005) 79#1 pp. 74-96 in JSTOR

- ↑ Stanley Karnow, In Our Image: America's Empire in the Philippines (1989) pp 308-9

- ↑ Satoshi Ara, "Food supply problem in Leyte, Philippines, during the Japanese Occupation (1942-44)," Journal of Southeast Asian Studies (2008) 39#1 pp 59-82.

- ↑ Francis K. Danquah, "Japan's Food Farming Policies in Wartime Southeast Asia: The Philippine Example, 1942-1944," Agricultural History (1990) 64#3 pp. 60-80 in JSTOR

- ↑ "World War II" in Ronald E. Dolan, ed. Philippines: A Country Study (1991) online

- ↑ Lebra, Joyce C. (1975). Japan's Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere in World War II: Selected Readings and Documents, p. 157.

- ↑ Lebra, p. 160.

- ↑ Lebra, p. 158.

- ↑ Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II, p253 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York

- ↑ Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The art of persuasion: World War II, p254 1976, Chelsea House Publishers, New York

- ↑ "Japanese Propaganda Booklet from World War II"

- ↑ "JAPANESE PSYOP DURING WWII"

- ↑ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 326 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

- ↑ Michael Baskett, The Attractive Empire: Transnational Japanese Film Culture in Imperial Japan, 978-0-8248-3223-0

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Weinberg, L. Gerhard. (2005). Visions of Victory: The Hopes of Eight World War II Leaders p.62-65.

- ↑ Storry, Richard (1973). The double patriots: a study of Japanese nationalism. Greenwood Press. pp. 317–319. ISBN 0-8371-6643-8.

- ↑ Norman, Rich (1973). Hitler's War Aims: Ideology, the Nazi State, and the Course of Expansion. W.W. Norton & Company Inc. p. 235.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Levine (1995), p. 92

- ↑ Stephan, J. J. (2002), Hawaii Under the Rising Sun: Japan's Plans for Conquest After Pearl Harbor, p. 159, ISBN 0-8248-2550-0

Sources

- Baskett, Michael (2008). The Attractive Empire: Transnational Film Culture in Imperial Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3223-0.

- Dower, John W. (1986). War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-394-50030-0; OCLC 13064585

- Iriye, Akira. (1999). Pearl Harbor and the coming of the Pacific War :a Brief History with Documents and Essays. Boston: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-21818-8; OCLC 40985780

- Lebra, Joyce C. (1975). Japan's Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere in World War II: Selected Readings and Documents. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-638265-4; OCLC 1551953

- Ugaki, Matome. (1991). Fading Victory: The Diary of Ugaki Matome, 1941-1945. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-3665-7

- Myers, Ramon Hawley and Mark R. Peattie. (1984) The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895-1945. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-10222-1

- Peattie, Mark R. (1988). "The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895-1945," in The Cambridge History of Japan: the Twentieth Century (editor, Peter Duus). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22357-7

- Vande Walle, Willy et al. The 'money doctors' from Japan: finance, imperialism, and the building of the Yen Bloc, 1894-1937 (abstract). FRIS/Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 2007-2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. |