Crime in Washington, D.C.

| Washington, D.C. | |

| Crime rates (2016) | |

| Crime type | Rate* |

|---|---|

| Homicide: | 18.8 |

| Forcible rape: | 53.4 |

| Robbery: | 589.1 |

| Aggravated assault: | 626.1 |

| Total violent crime: | 1,244.4 |

| Burglary: | 526 |

| Larceny-theft: | 4,082.3 |

| Motor vehicle theft: | 574.1 |

| Arson: | 7.9 |

| Total property crime: | 5,182.5 |

| Notes * Number of reported crimes per 100,000 population. |

|

| Source: Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Crime in the United States | |

Crime in Washington, D.C. (formally known as the District of Columbia), is directly related to the city's changing demographics, geography, and unique criminal justice system. The District's population reached a peak of 802,178 in 1950. However, shortly thereafter, the city began losing residents and by 1980 Washington had lost one-quarter of its population. The population loss to the suburbs also created a new demographic pattern, which divided affluent neighborhoods west of Rock Creek Park from more crime-ridden and blighted areas to the east.

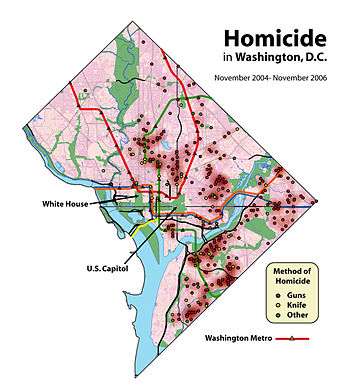

Despite being the headquarters of multiple federal law enforcement agencies, such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the nationwide crack epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s greatly affected the city and led to large increases in crime.[1] The number of homicides in Washington peaked in 1991 at 688[2] (a rate of nearly 80 homicides per 100,000 residents), and the city eventually became known as the "murder capital" of the United States.[3]

The crime rate started to fall in the mid-1990s as the crack epidemic gave way to economic revitalization projects. Gentrification efforts have also started to transform the demographics of distressed neighborhoods, recently leading to the first rise in the District's population in 60 years.[4]

By the mid-2000s, crime rates in Washington dropped to their lowest levels in over 20 years. As in many major cities, crime remains a significant factor in D.C., especially in the city's northwestern neighborhoods, which tend to be more affluent, draw more tourists, and have more vibrant nightlife.[5] Violent crime also remains a problem in Ward 8, which has the city's highest concentration of poverty.[6]

Statistics

| Crime Trends, 1995-2013[7] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Violent Crime | Change | Property Crime | Change |

| 1995 | 2,661.4 | - | 9,512.1 | - |

| 1996 | 2,469.8 | -7.1% | 9,426.9 | -0.9% |

| 1997 | 2,024.0 | -18% | 7,814.9 | -17% |

| 1998 | 1,718.5 | -15% | 7,117.0 | -8.9% |

| 1999 | 1,627.7 | -5.3% | 6,439.3 | -9.5% |

| 2000 | 1,507.9 | -7.4% | 5,768.6 | -10.4% |

| 2001 | 1,602.4 | 6.3% | 6,139.9 | 6.4% |

| 2002 | 1,632.9 | 1.9% | 6,389.4 | 4.1% |

| 2003 | 1,624.9 | -0.5% | 5,863.5 | -8.2% |

| 2004 | 1,371.2 | -15.6% | 4,859.1 | -17.1% |

| 2005 | 1,380.0 | 0.6% | 4,489.8 | -7.6% |

| 2006 | 1,508.4 | 9.3% | 4,653.8 | 3.7% |

| 2007 | 1,414.3 | -6.2% | 4,913.9 | 5.6% |

| 2008 | 1,437.7 | 1.7% | 5,104.6 | 3.9% |

| 2009 | 1,345.9 | -6.8% | 4,745.4 | -7.6% |

| 2010 | 1,241.1 | -7.8% | 4,510.1 | -5% |

| 2011 | 1,130.3 | -8.9% | 4,581.3 | 1.6% |

| 2012 | 1,177.9 | 4.2% | 4,628.0 | 1.0% |

| 2013 | 1,219 | 3.5% | 4,790.7 | 3.5% |

| 2014 | 1244.4 | 1.9% | 5182.5 | 8.2% |

| 1995 | 2,661.4 | - | 9,512.1 | - |

| 2014 | 1,244.4 | -53.3% | 5,182.5 | -45.6% |

According to Uniform Crime Report statistics compiled by the FBI, there were 1,330.2 violent crimes per 100,000 people reported in the District of Columbia in 2010. There were also 4,778.9 property crimes per 100,000 reported during the same period.[8]

The average violent crime rate in the District of Columbia from 1960 through 1999 was 1,722 violent crimes per 100,000 population,[9] and violent crime has decreased significantly since after peaking in the mid 1990s, by 50% in the 1995–2010 period (with property crime has decreasing by 49.8% during the same period). However, violent crime is still more than three times the national average of 403.6 reported offenses per 100,000 people in 2010.[10]

In the early 1990s, Washington, D.C., was known as the "murder capital",[11] experiencing 474 homicides in 1990.[12] The elevated crime levels were associated with the introduction of crack cocaine during the late 1980s and early 1990s. The crack was brought into Washington, D.C. by Colombian cartels and sold in drug markets such as "The Strip" (the largest in the city) located a few blocks north of the United States Capitol.[13] A quarter of juveniles with criminal charges in 1988 tested positive for drugs.[11]

The number of homicides per year in Washington, D.C., peaked at 479 in 1991,[14] followed by a downward trend in the late 1990s. In 2000, 242 homicides occurred,[12] and the downward trend continued in the 2000s. In 2012, Washington, D.C. had only 92 homicides in 91 separate incidents, the lowest annual tally since 1963.[15] The Metropolitan Police Department's official tally is 88 homicides, but that number does not include four deaths that were ruled self-defense or justifiable homicide by citizen.[15] The cause of death listed on the four case records is homicide and MPD includes those cases in tallying homicide case closures at the end of the year.[15]

As Washington neighborhoods undergo gentrification, crime has been displaced further east. Crime in neighboring Prince George's County, Maryland, initially experienced an increase, but has recently witnessed steep declines as poorer residents moved out of the city into the nearby suburbs.[16] Crime has declined both in the District and the suburbs in recent years. In fact, the influx of more affluent new residents in the city has not led to an uptick in robberies or property crimes in gentrifying areas, including Columbia Heights, Adams Morgan, Mount Pleasant, Dupont Circle, Logan Circle, and Shaw. There was an average of 11 robberies each day across the District of Columbia in 2006,[5] which is far below the levels experienced in the 1990s.[17]

In 2008, 42 crimes in the District were characterized as hate crimes; over 70% of the reports classified as hate crimes were a result of a bias against the victim's perceived sexual orientation.[18] Those findings continue the trend from previous years, although the total number of hate crimes is down from 57 in 2006,[19] and 48 in 2005.[20] By 2012, the number of hate crimes reported were 81, and dropped to 70 in 2013.[21]

Criminal justice

Law enforcement

Law enforcement in Washington, D.C. is complicated by a network of overlapping federal and city agencies. The primary agency responsible for law enforcement in the District of Columbia is the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD). The MPD is a city agency headed by the Chief of Police, currently Cathy L. Lanier, who is appointed by the mayor. The Metropolitan Police has 3,800 sworn officers and operates much like other municipal police departments elsewhere in the country. However, given the unique status of Washington as the United States capital, the MPD is adept at providing crowd control and security at large events.[22] Despite its name, the MPD only serves within the boundaries of the District of Columbia and does not have jurisdiction within the surrounding Washington Metropolitan Area.

Several other local police agencies have jurisdiction within the District of Columbia, including: the District of Columbia Protective Services Police Department, which is responsible for all properties owned or leased by the city government; and the Metro Transit Police Department, which has jurisdiction within Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority stations, trains, and buses. Alongside local law enforcement agencies, nearly every federal law enforcement agency has jurisdiction within Washington, D.C. The most visible federal police agencies are the United States Park Police, which is responsible for all parkland in the city, the United States Secret Service, and the United States Capitol Police.

A number of special initiatives undertaken by the Metropolitan Police Department in order to combat violent crime have gained particular public attention. Most notable are the city's use of "crime emergencies", which when declared by the Chief of Police, allow the city to temporarily suspend officer schedules and assign additional overtime in order to increase police presence.[23]

Despite the fact that crime emergencies do appear to reduce crime when enacted,[24] critics fault the city for relying on such temporary stop-gap measures.[25] In 2003, the city launched its Gang Intervention Project to combat the then-recent upward trend in Latino gang violence, primarily in the Columbia Heights and Shaw neighborhoods. The initiative was claimed a success when gang-related violence declined almost 90% from the start of the program to November 2006.[26]

The most controversial program designed to deter crime was a system of police checkpoints in neighborhoods particularly affected by violence. The checkpoints, in place from April 2008 through June 2008,[27] were used in the Trinidad neighborhood of Northeast Washington. The program operated by stopping cars entering a police-designated area; officers then turned away those individuals who did not live or have business in the neighborhood. Despite protests by residents, the MPD claimed the checkpoints to be a successful tool in preventing violent crime.[28] However, in July 2010, a federal appeals court found that the checkpoints violated residents' constitutional rights. The police had no plans to continue to use the practice—with declining crime rates—but D.C. Attorney General Peter Nickles said that officers would work to find a "more creative way to deal with very unusual circumstances that is consistent with the Fourth Amendment."[29]

In 2012, the first female Chief of Police of DC, Cathy L. Lanier, was hired by Mayor Vincent Gray. Between 2014 and 2016, there was a spike in homicides and other violent crimes; with a 54% increase in homicides between 2014 and 2015.[30] In 2016, Chief Lanier resigned, mentioning her frustration with the problem of the "revolving door for offenders" contributing to high rates of violent crimes in the District.[31]

Court system

The Superior Court of the District of Columbia hears all local civil and criminal cases in Washington, D.C. Despite the fact that the court is technically a branch of the D.C. government, the Superior Court is funded and operated by the U.S. federal government. In addition, the court's judges are appointed by the President of the United States.[32] The D.C. Superior Court should not, however, be confused with the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, which only hears cases dealing with violations of federal law.[33]

The District of Columbia has a complicated criminal prosecution system. The Attorney General of the District of Columbia only has jurisdiction in civil proceedings and prosecuting minor offenses such as low-level misdemeanors and traffic violations.[34] All federal offenses, local felony charges (i.e. serious crimes such as robbery, murder, aggravated assault, grand theft, and arson), and most local misdemeanors are prosecuted by the United States Attorney for the District of Columbia.[35] United States Attorneys are appointed by the President and overseen by the United States Department of Justice.[36] This differs from elsewhere in the country where 93% of local prosecutors are directly elected and the remainder are appointed by local elected officials.[37]

The fact that the U.S. Attorneys in the District of Columbia are neither elected nor appointed by city officials leads to criticism that the prosecutors are not responsive to the needs of local residents.[38] For example, new felony prosecutions by the U.S. Attorneys in the District of Columbia have fallen 34%; from 8,016 in 2003 to 5,256 in 2007. The number of resolved felony cases has also fallen by nearly half; from 10,206 in 2003 to 5,534 in 2007. In contrast, the number of misdemeanor and civil cases prosecuted and resolved by the D.C. Attorney General's office has remained constant over the same time period.[39] The U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia cites the drop in prosecutions to a 14% cut in its budget. The cuts have caused the office to decrease the number of federal prosecutors from a high of 110 in 2003 to 76 in 2007.[40]

Efforts to create the position of D.C. district attorney regained attention in 2008. The D.C. district attorney would be elected and have jurisdiction over all local criminal cases, thereby streamlining prosecution and making the justice system more accountable to residents. However, progress to institute such an office has stalled in Congress.[41]

Prison system

Under the National Capital Revitalization and Self-Government Improvement Act of 1997, prisoners were put under custody of the Federal Bureau of Prisons; the Lorton Correctional Complex, a prison operated by the District government in Lorton, Virginia, was closed in 2000. Offenders serving short sentences for misdemeanors serve time either at the Central Detention Facility or the Correctional Treatment Facility, both run by the District of Columbia Department of Corrections.[42]

Approximately 6,500 prisoners convicted in the District of Columbia are sent to Bureau of Prison facilities around the United States, including over a 1,000 sent to West Virginia, and another 1,000 to North Carolina.[42] The Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency was established, under the National Capital Revitalization and Self-Government Improvement Act, to oversee probationers and parolees, and provide pretrial services. The functions were previously handled by the D.C. Superior Court and the D.C. Pretrial Services Agency.[43]

As of 2007 almost 7,000 prisoners sentenced in District of Columbia courts had been imprisoned in 75 prisons in 33 states.[44] As of 2010 5,700 prisoners sentenced in DC courts had been imprisoned in federal-owned or leased properties in 33 states.[45] As of 2010 felons sentenced under D.C. law altogether made up almost 8,000 prisoners, or about 6% of the total BOP population, and they resided in 90 facilities.[46] As of 2013 about 20% of the DC-sentenced prisoners were incarcerated over 500 miles (800 km) from Washington, D.C.[45]

Rivers Correctional Institution, a private prison in North Carolina, was purpose-built to house D.C. inmates, and as of 2007 about 66% of the prisoners were DC-sentenced inmates.[44] In 2009 the prison housed about 800-900 prisoners sentenced under DC law.[47] As of 2013 up to about 33% of the prisoners at United States Penitentiary, Big Sandy in Kentucky had been convicted of DC crimes.[48]

Gun laws

Washington, D.C., has enacted a number of strict gun-restriction laws. The Firearms Control Regulations Act of 1975 prohibited residents from owning handguns, excluding those registered prior to February 5, 1977; however, this law was subsequently overturned in March 2007 by the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in Parker v. District of Columbia.[50]

The ruling was upheld in June 2008 by the Supreme Court of the United States in District of Columbia v. Heller. Both courts held that the city's handgun ban violated individuals' Second Amendment right to gun ownership.[51] However, the ruling does not repeal all forms of gun control; laws requiring firearm registration remain in place, as does the city's assault weapon ban.[52] Additionally, city laws still prohibit carrying guns, both openly and concealed.[53]

Critics, citing numerous statistics, have questioned the efficiency of these restrictions. The combination in Washington of strict gun-restriction laws and high levels of gun violence is sometimes used to criticize gun-restriction laws in general as ineffective. A significant portion of firearms used in crime are either obtained from a traditional gun store or from a sporting goods store.[54][55] Results from the ATF's Youth Crime Gun Interdiction Initiative indicate that the percentage of imported guns involved in crimes is tied to the stringency of local firearm laws.[54]

Washington, D.C., has tried a number of other strategies to deal with gun violence. In 1995, the Metropolitan Police Department conducted Operation Ceasefire, a gun-violence crackdown initiative involving intense gun law enforcement, in conjunction with the United States Attorney's Office.[56] This initiative resulted in seizure of 282 firearms in its first four months, mainly 9mm, .380 ACP, and .25 ACP pistols, and .38 caliber revolvers, most of which were purchased in Maryland and Virginia.[57]

References

- ↑ "DEA History Book, 1985 - 1990". Drug Enforcement Administration. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ↑ "District Crime Data at a Glance". DC Metropolitan Police Department. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ↑ Urbina, Ian (2006-07-13). "Washington Officials Try to Ease Crime Fear". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ↑ Liz Farmer (2010-10-21). "D.C.'s population grows for first time in 60 years". Washington Examiner. Retrieved 2011-08-27.

- 1 2 Klein, Allison; Dan Keating (2006-10-13). "Liveliest D.C. Neighborhoods Also Jumping With Robberies". The Washington Post. p. A01. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ↑ "DC Crime Statistics: Jan. 1 to March 24, 2011". The Washington Post. 2011-03-24. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ↑ "Uniform Crime Reports". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on 2004-10-24. Retrieved 2014-11-20.

- ↑ "Crime in the United States by Region, Geographic Division, and State, 2009-2010". Crime in the United States, 2007. September 2009. Retrieved 2011-08-27.

- ↑ Joanne Savage, "Interpreting 'Percent Black:' An Analysis of Race and Violent Crime in Washington, DC", Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice Volume:4 Issue:1/2 (2006), 29–63.

- ↑ "Violent Crime". Crime in the United States, 2010. 2010. Retrieved 2012-01-02.

- 1 2 Vulliamy, Ed (1994-10-23). "Drugs: Redemption in Crack City". The Observer.

- 1 2 "A Study of Homicides in the District of Columbia" (PDF). Metropolitan Police Department, District of Columbia. October 2001. p. 22.

- ↑ Isikoff, Michael (1989-09-03). "Making a D.C. Link to the Colombian Source". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "D.C. homicides drop by half in last decade". Washington Times. January 2012.

- 1 2 3 Homicide Watch D.C., "92," , January 1, 2013

- ↑ "Crime in Prince George's is at lowest level since 1975, police say". Gazette.net. 2010-01-14. Retrieved 2011-12-10.

- ↑ "Citywide Crime Statistics Annual Totals, 1993-2005". Metropolitan Police Department. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ↑ "Table 13 - DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA - Hate Crime Statistics 2008:". Hate Crime Statistics, 2008. October 2009. Retrieved 2011-08-27.

- ↑ "District of Columbia Hate Crime Incidents per Bias Motivation and Quarter". Hate Crime Statistics, 2006. November 2007. Retrieved 2011-08-27.

- ↑ "District of Columbia Hate Crime Incidents per Bias Motivation and Quarter". Hate Crime Statistics, 2005. October 2006. Retrieved 2011-08-27.

- ↑ Noble, Andrea (19 August 2014). "Race-based hate crimes spike in D.C.; whites most common victims, but underreporting feared". Washington Times. The Washington Times, LLC. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ↑ "Brief History of the MPDC". Metropolitan Police Department. Retrieved 2011-08-27.

- ↑ Klein, Allison (2006-07-12). "Police Chief Declares D.C. Crime Emergency". The Washington Post. p. A01. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ↑ Klein, Allison (2006-10-21). "Crackdown Is Yielding Results, Ramsey Says". The Washington Post. p. B02. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ↑ "D.C.'s Crime Emergency". The Washington Post. 2006-07-13. p. A22. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ↑ Schwartzman, Paul (2006-11-16). "Gang Violence Has Declined, Mayor Says". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ↑ Gleaton, Idrissa (2008-06-12). "DC Police End Neighborhood Checkpoints". WUSA Channel 9. Retrieved 2012-01-02.

- ↑ Alexander, Keith L.; V. Dion Haynes (2008-06-08). "In Face of Protests, Police Call Area Checkpoints a Success". The Washington Post. p. C06. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ↑ Glod, Maria (2010-07-11). "Federal Courts Says D.C. Police Checkpoints Were Unconstitutional". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-09-06.

- ↑ http://mpdc.dc.gov/page/district-crime-data-glance

- ↑ http://dailycaller.com/2016/09/06/dc-police-chief-fed-up-with-criminal-revolving-door-lack-of-action/

- ↑ "About the District of Columbia Courts". District of Columbia Courts. Retrieved 2008-12-06.

- ↑ "United States District Courts". Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. Retrieved 2008-12-06.

- ↑ "Attorney General Duties". Office of the Attorney General. Retrieved 2011-08-27.

- ↑ "About Us". United States Attorney's Office for the District of Columbia. Retrieved 2008-12-06.

- ↑ "United States Attorneys Mission Statement". United States Department of Justice. Retrieved 2008-12-06.

- ↑ Boyd, Eugene (2008-04-24). "Statement on the District of Columbia Attorney Act, H.R. 1296" (PDF). House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. Retrieved 2008-12-06.

- ↑ "Establishment of an Office of the District Attorney Advisory Referendum Approval Resolution of 2002" (PDF). Council of the District of Columbia. 2002-07-02. Retrieved 2008-12-06.

- ↑ "2007 Statistical Summary" (PDF). District of Columbia Courts. Retrieved 2008-12-06.

- ↑ Leonnig, Carol D. (2007-10-21). "D.C. Sees Sharp Drop In Federal Prosecution". Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ↑ Sheridan, Mary Beth (2008-04-25). "House Panel Considers Prosecutor Change". The Washington Post. p. B04. Retrieved 2008-12-06.

- 1 2 "Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency for the District of Columbia - FY2009 Budget Request" (PDF). Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-08-13. Retrieved 2011-08-27.

- ↑ Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency (February 2006). "Supervising Criminal Offenders in Washington, D.C" (PDF). Corrections Today: 46–49. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-16.

- 1 2 Pierre, Robert E. "N.C. Prison Doesn't Serve D.C. Inmates Well, Critics Say" (Archive). Washington Post. October 14, 2007. Retrieved on February 5, 2016.

- 1 2 Kruzel, John. "Visitation Slights: How Two Policies Stack the Deck Against D.C. Inmates" (Archive). May 22, 2013. Retrieved on February 5, 2016.

- ↑ Fornaci, Philip (Director of the DC Prisoners' Project). "Federal Bureau of Prisons Oversight Hearing" (Archive). Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security. U.S. House of Representatives Committee on the Judiciary. July 21, 2009. p. 1/11. Retrieved on February 5, 2016.

- ↑ Fornaci, Philip (Director of the DC Prisoners' Project). "Federal Bureau of Prisons Oversight Hearing" (Archive). Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security. U.S. House of Representatives Committee on the Judiciary. July 21, 2009. p. 2. Retrieved on February 5, 2016.

- ↑ Associated Press (September 14, 2013). "Feds May Seek Death Sentence In Ky. Inmate Slaying". CBS Local (Cleveland). Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2013. () "Big Sandy is known for housing high-profile inmates. And because the federal Bureau of Prisons automatically takes custody of people convicted in Washington, at any time, up to a third of the facility’s 1,445 inmates were convicted in the city."

- ↑ http://www.disastercenter.com/crime/index.html

- ↑ "Court strikes down D.C. handgun law". CNN. 2007-03-09. Archived from the original on 2008-09-19. Retrieved 2011-08-27.

- ↑ Barnes, Robert (2008-06-26). "Supreme Court Strikes Down D.C. Ban on Handguns". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ↑ Nakamura, David (2008-06-26). "D.C. Attorney General: All Guns Must Be Registered". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ↑ "NRA-ILA Firearms Laws for the District of Columbia" (PDF). National Rifle Association, Institute for Legislative Action. April 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-08.

- 1 2 "Youth Crime Gun Interdiction Initiative". U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. 2008.

- ↑ Wintemute, Garen (2000). "Guns and Gun Violence". In Blumstein, Alfred; Wallman, Joel. The Crime Drop in America. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79712-2.

- ↑ Duggan, Paul (1995-03-11). "Area Officials Briefed On D.C. Anti-Gun Effort; U.S. Attorney Asks Other Jurisdictions for Cooperation". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Lewis, Nancy (1995-10-26). "Officials Say D.C. Anti-Gun Program Seems to Be Working". The Washington Post.

Further reading

- "HOUSING D.C. FELONS FAR AWAY FROM HOME: EFFECTS ON CRIME, RECIDIVISM AND REENTRY" (Archive). Testimony before the United States House of Representatives Committee on Government Reform and Oversight Subcommittee on Federal Workforce, Postal Service, and the District of Columbia. Presented May 5, 2010.

- PDF version of Testimony of (Archive): Lappin, Harley G. (Director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons).

- PDF version of Testimony of (Archive): Fornaci, Philip, Director of the D.C. Prisons Project