Gyanvapi Mosque

| Gyan Vapi mosque | |

|---|---|

| |

Location in Uttar Pradesh, India | |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Varanasi, India |

| Geographic coordinates | 25°18′40″N 83°00′38″E / 25.311229°N 83.010461°ECoordinates: 25°18′40″N 83°00′38″E / 25.311229°N 83.010461°E |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| State | Uttar Pradesh |

| Architectural description | |

| Founder | Aurangzeb |

| Completed | 1664 |

| Specifications | |

| Dome(s) | 3 |

| Minaret(s) | 2 |

The Gyanvapi mosque is located in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India. It was constructed by the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, on the site of the demolished Kashi Vishwanath temple. It is located north of Dashashwamedh Ghat, near Lalita Ghat along the river Ganga.

It is a Jama Masjid located in the heart of the Varanasi city.[1] It is administered by Anjuman Inthazamiya Masajid (AIM).[2]

History

The mosque was built by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in 1664 CE, after destroying a Hindu temple.[3]:1 The remnants of the Hindu temple can be seen on the walls of the Gyanvapi mosque.[4]

The demolished temple is believed by Hindus to be an earlier restoration of the original Kashi Vishwanath temple. The original temple had been destroyed and rebuilt a number of times. The temple structure that existed prior to the construction of the mosque was most probably built by Raja Man Singh during Akbar's reign.[5] Aurangzeb's demolition of the temple was also probably attributed to the escape of the Maratha king Shivaji and the rebellion of local zamindars (landowners). Jai Singh I, the grandson of Raja Man Singh, is alleged to have facilitated Shivaji's escape from Agra. Some of the zamindars were alleged to helped Shivaji avoid the Mughal authorities. In addition, there were allegations of Brahmins interfering with the Islamic teaching. The temple's demolition was intended as a warning to the anti-Mughal factions and Hindu religious leaders in the city.[5]

Maulana Abdus Salam contests the claim that a temple was destroyed to build the mosque. He states that the foundation of the mosque was laid by the third Mughal emperor Akbar. He also adds that Akbar's son and Aurangzeb's father Shah Jahan started a madrasah called Imam-e-Sharifat at the site of the mosque in 1048 hijri (1638-39 CE).[6][7] Where as, The remains of the erstwhile temple can be seen in the foundation, the columns and at the rear part of the mosque[8] clearly indicating the mosque was constructed on the demolished temple, using the same foundation, pillars etc.

Hindu worship in the Gyanvapi precinct

Around 1750, the Maharaja of Jaipur commissioned a survey of the land around the site, with the objective of purchasing land to rebuild the Kashi Vishwanath temple. The survey map provides detailed information about the buildings in this area and information about their ownership. This survey shows that the edges of the rectangular Gyanvapi mosque precinct were lined up with the residences of Brahmin priests.[3]:85

Describing the site in 1824, British traveler Reginald Heber wrote that "Aulam Gheer" (Alamgir I i.e. Aurangzeb) had defiled a sacred Hindu spot and built a mosque on it. He stated that Hindus considered this spot more sacred than the adjoining new Kashi Vishwanath temple. He described the site as a "temple court", which was crowded with tame bulls and naked devotees chanting the name of Rama.[9]

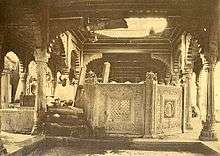

The wall

A temple structure can be seen at the mosque's rear wall, long believed to be a remnant of the original Kashi Vishwanath temple. In 1822, James Prinsep captioned an illustration of the rear wall as "temple of Vishveshvur" in his Benares Illustrated. The Hindus worshiped the plinth of the mosque as the plinth of the old Kashi Vishwanath temple.[10][11]:5–6 M. A. Sherring (1868) wrote that the "extensive remains" of the temple destroyed by Aurangzeb were still visible, forming "a large portion of the western wall" of the mosque. He mentioned that the remnant structure also had Jain and Buddhist elements, besides the Hindu ones.[12]

Christian missionary Edwin Greaves (1909), of the London Missionary Society, described the site as follows:

At the back of the mosque and in continuation of it are some broken remains of what was probably the old Bishwanath Temple. It must have been a right noble building ; there is nothing finer, in the way of architecture in the whole city, than this scrap. A few pillars inside the mosque appear to be very old also.— Edwin Greaves, Kashi the city illustrious, or Benares, 1909[13]

Gyan Vapi well

The mosque is named after a well, the Gyan Vapi ("the well of knowledge"), which is located within the mosque precincts. The legends mentioned by the Hindu priests state that the lingam of the original temple was hidden in this well, when the temple was destroyed.[3]:5[14]

During the British period, the Gyan Vapi well was a regular destination on the Hindu pilgrimage routes in the city.[3]:5 Reginald Heber, who visited the site in 1824, mentioned that the water of the Gyan Vapi — brought by a subterraneous channel of the Ganges — was considered holier than the Ganges itself by the Hindus.[9] M. A. Sherring, in his 1868 book The Sacred City of the Hindus, mentioned that people visited the Gyan Vapi "in multitudes", and threw in offerings that had polluted the well.[12] Greaves (1909) mentioned that a Brahmin (Hindu priest) sat at a stone screen surrounding the Gyan Vapi. The worshippers would come to the well, and receive sacred water from the priest.[13]

During the Hindu-Muslim riot of 1809, a Muslim mob killed a cow (sacred to Hindus) on the spot, and spread its blood into the sacred water of the well. In retaliation, the Hindus threw rashers of bacon (haram to Muslims) into windows of several mosques. Subsequently, both the parties took to arms, resulting in several deaths, before the British administration quelled the riot.[3]:33[9]

Colonnade

In 1828, Baija Bai, widow of the Maratha ruler Daulat Rao Scindhia of Gwalior State, constructed a colonnade in the Gyan Vapi precinct. Sherring (1868) mentioned that the well was surrounded by this low-roofed colonnade, which had over 40 stone pillars, organized in 4 rows. To the east of the colonnade, there was a 7-feet high stone statue of Nandi bull, gifted by the Raja of Nepal. To further east, there was a temple dedicated to Shiva, sponsored by the Rani of Hyderabad. On the south side of the colonnade, there were two small shrines (one stone and the other marble), enclosed by an iron palisade. In this courtyard, about 150 yards from the mosque, there was a 60-feet high temple, claimed to be "Adi-Bisheswar", anterior to the original Kashi Vishwanath temple.[12]

Sherring also described a large collection of statues of Hindu gods, called "the court of Mahadeva" by the locals. According to him, the statues were not modern, and were probably taken "from the ruins of the old temple of Bisheswar". He also wrote that the Muslims had built a gateway in the midst of the platform in front of the mosque, but were not allowed to use it by the Hindus. Violence was prevented by the intervention of the Magistrate of Benares. Sherring further stated that the Hindus worshipped a peepal tree that overhanged the gateway, and the Hindus did not allow Muslims to "pluck a single leaf from it."[12]

Greaves (1909) also mentioned the colonnade and the bull statue, stating that the statue was highly venerated and "freely worshipped". Close to this statue, there was a temple dedicated to Gauri Shankar (Shiva and Parvati). Greaves further wrote that there were "one or two other small temples" in the same open space, and there was a large Ganesha statue placed near the well.[13]

Muslim worship

M. A. Sherring (1868), described the mosque (minus the temple remnants) as plain, with few carvings. Its walls were "besmeared with a dirty white-wash, mixed with a little colouring matter." Sherring mentioned that the Hindus unwillingly allowed the Muslims to retain the mosque, but claimed the courtyard and the wall. The Muslims had to use the side entrance, because the Hindus would not allow them to use the front entrance through the courtyard.[12] Edwin Greaves (1909) stated that the mosque was "not greatly used", but had always been an "eyesore" to the Hindus.[13]

Demolition concerns

In 1742, the Maratha ruler Malhar Rao Holkar made a plan to demolish the mosque and reconstruct Vishweshwar temple at the site. However, his plan did not materialize, partially because of intervention by the Nawabs of Lucknow, who controlled the territory. Later, in 1780, his daughter-in-law Ahilyabai Holkar constructed the present Kashi Vishwanath Temple adjacent to the mosque.[3]:2

In the 1990s, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) campaigned to reclaim the sites of the mosques constructed after demolition of Hindu temples. After the demolition of the Babri mosque in December 1992, about a thousand policemen were deployed to prevent a similar incident at the Gyanvapi mosque site.[15] The Bharatiya Janata Party leaders, who supported the demand for reclaiming Babri mosque, opposed VHP's similar demand for Gyanvapi, on the grounds that it was an actively used mosque.[16]

The mosque now receives protection under the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991.[17] Entry into the mosque precinct is restricted, and photography of the mosque's exterior is banned.[11]

Architecture

The façade is modeled partially on the Taj Mahal's entrance.[5] The remains of the erstwhile temple can be seen in the foundation, the columns and at the rear part of the mosque.[8]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gyanvapi Mosque. |

- Other notable mosques in Varanasi: Ganj-e-Shaheedan Mosque and Chaukhamba Mosque

- Conversion of non-Muslim places of worship into mosques

References

- ↑ Diane P. Mines; Sarah Lamb (2002). Everyday Life in South Asia. Indiana University Press. pp. 344–. ISBN 0-253-34080-2.

- ↑ "VHP game in Benares, with official blessings". Frontline. S. Rangarajan for Kasturi & Sons. 12 (14-19): 14. 1995.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Madhuri Desai (2007). Resurrecting Banaras: Urban Space, Architecture and Religious Boundaries. ProQuest. ISBN 978-0-549-52839-5.

- ↑ Siddharth Varadarajan (2011-11-11). "Force of faith trumps law and reason in Ayodhya case". The Hindu.

- 1 2 3 Catherine B. Asher (24 September 1992). Architecture of Mughal India. Cambridge University Press. pp. 278–279. ISBN 978-0-521-26728-1.

- ↑ Diane P. Mines and Sarah Lamb (2002). Everyday Life in South Asia. Indiana University Press. p. 344. ISBN 9780253340801.

- ↑ Suvir Kaul. The Partitions of Memory: The Afterlife of the Division of India. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 279. ISBN 9781850655831.

- 1 2 Vanessa Betts; Victoria McCulloch (30 October 2013). Delhi to Kolkata Footprint Focus Guide. Footprint Travel Guides. pp. 108–. ISBN 978-1-909268-40-1.

- 1 2 3 Reginald Heber (1829). Narrative of a journey through the upper provinces of India, from Calcutta to Bombay, 1824-1825. Philadelphia, Carey, Lea & Carey. pp. 257–258.

- ↑ James Prinsep. Benares Illustrated in a Series of Drawings. p. 29. ISBN 9788171241767.

- 1 2 Madhuri Desai (2003). "Mosques, Temples, and Orientalists: Hegemonic Imaginations in Banaras" (PDF). Traditional Dwellings and Settlements. XV (1): 23–37.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Matthew Atmore Sherring (1868). The Sacred City of the Hindus: An Account of Benares in Ancient and Modern Times. Trübner & co. pp. 55–56.

- 1 2 3 4 Edwin Greaves (1909). Kashi the city illustrious, or Benares. Allahabad: Indian Press. pp. 80–82.

- ↑ Good Earth Varanasi City Guide. Eicher Goodearth Limited. 2002. p. 95. ISBN 978-81-87780-04-5.

- ↑ Sanjoy Majumder (2004-03-25). "Cracking India's Muslim vote". Uttar Pradesh: BBC News.

- ↑ Manjari Katju (1 January 2003). Vishva Hindu Parishad and Indian Politics. Orient Blackswan. pp. 113–114. ISBN 978-81-250-2476-7.

- ↑ "Mosques will not be surrendered, says Babri panel". Indian Express. New Delhi. Press Trust Of India. 1999-09-15.