Hanaoka Seishū

| Hanaoka Seishū | |

|---|---|

Hanaoka Seishū | |

| Born |

October 23, 1760[1] Hirayama, Naga District, Kii Province, (now Wakayama Prefecture), Japan |

| Died |

November 21, 1835 (aged 75) Japan |

| Residence | Japan |

| Citizenship | Japan |

| Nationality | Japan |

| Fields | Medicine, surgery |

| Institutions | Japan |

| Alma mater | Kyoto, Japan |

| Academic advisors | Nangai Yoshimasu (1750-1813)[2] |

| Known for | first to perform surgery using general anesthesia |

| Influences |

Yoshio Kōsaku (1724-1800)[3][4] Kenryu Yamato (1740-1780) Hanaoka Jikido |

| Influenced |

Shutei Nakagawa (1773–1850)[5] Gencho Homma (1804-1872)[1][6] |

Hanaoka Seishū (華岡 青洲, October 23, 1760 – November 21, 1835) was a Japanese surgeon of the Edo period with a knowledge of Chinese herbal medicine, as well as Western surgical techniques he had learned through Rangaku (literally "Dutch learning", and by extension "Western learning"). Hanaoka is said to have been the first to perform surgery using general anesthesia.

History

Hanaoka studied medicine in Kyoto, and became a medical practitioner in Wakayama prefecture, located near Osaka, where he was born. Seishū Hanaoka learned traditional Japanese medicine as well as Dutch-imported European surgery. Due to the nation's self-imposed isolation policy of Sakoku,[7] few foreign medical texts were permitted into Japan at that time. This limited the exposure of Hanaoka and other Japanese physicians to Western medical developments.

Perhaps the most notable Japanese surgeon of the Edo period, Hanaoka was famous for combining Dutch and Japanese surgery and introducing modern surgical techniques to Japan.[6] Hanaoka successfully operated for hydrocele, anal fistula, and even performed certain kinds of plastic surgery. He was the first surgeon in the world who used the general anaesthesia in surgery and who dared to operate on cancers of the breast and oropharynx, to remove necrotic bone, and to perform amputations of the extremities in Japan.[6]

Hua Tuo and mafeisan

Hua Tuo (華佗, ca. AD 145-220) was a Chinese surgeon of the 2nd century AD. According to the Records of Three Kingdoms (ca. AD 270) and the Book of the Later Han (ca. AD 430), Hua Tuo performed surgery under general anesthesia using a formula he had developed by mixing wine with a mixture of herbal extracts he called mafeisan (麻沸散).[8] Hua Tuo reportedly used mafeisan to perform even major operations such as resection of gangrenous intestines.[8][9][10] Before the surgery, he administered an oral anesthetic potion, probably dissolved in wine, in order to induce a state of unconsciousness and partial neuromuscular blockade.[8]

The exact composition of mafeisan, similar to all of Hua Tuo's clinical knowledge, was lost when he burned his manuscripts, just before his death.[11] The composition of the anesthetic powder was not mentioned in either the Records of Three Kingdoms or the Book of the Later Han. Because Confucian teachings regarded the body as sacred and surgery was considered a form of body mutilation, surgery was strongly discouraged in ancient China. Because of this, despite Hua Tuo's reported success with general anesthesia, the practice of surgery in ancient China ended with his death.[8]

The name mafeisan combines ma (麻, meaning "cannabis, hemp, numbed or tingling"), fei (沸, meaning "boiling or bubbling"), and san (散, meaning "to break up or scatter", or "medicine in powder form"). Therefore, the word mafeisan probably means something like "cannabis boil powder". Many sinologists and scholars of traditional Chinese medicine have guessed at the composition of Hua Tuo's mafeisan powder, but the exact components still remain unclear. His formula is believed to have contained some combination of:[8][11][12][13]

- bai zhi (Angelica dahurica),

- cao wu (草烏, Aconitum kusnezoffii, Aconitum kusnezoffii, Kusnezoff's monkshood, or wolfsbane root),

- chuān xiōng (Ligusticum wallichii, or Szechuan lovage),

- dong quai (Angelica sinensis, or "female ginseng"),

- wu tou (烏頭, Aconitum carmichaelii, rhizome of Aconitum, or Chinese monkshood"),

- yang jin hua (洋金花, Flos Daturae metelis, or Datura stramonium, jimson weed, devil's trumpet, thorn apple, locoweed, moonflower),

- ya pu lu (Mandragora officinarum)

- rhododendron flower, and

- jasmine root.

Others have suggested the potion may have also contained hashish,[9] bhang,[10] shang-luh,[14] or opium.[15] Victor H. Mair wrote that mafei "appears to be a transcription of some Indo-European word related to "morphine"."[16] Some authors believe that Hua Tuo may have discovered surgical analgesia by acupuncture, and that mafeisan either had nothing to do with or was simply an adjunct to his strategy for anesthesia.[17] Many physicians have attempted to re-create the same formulation based on historical records but none have achieved the same clinical efficacy as Hua Tuo's. In any event, Hua Tuo's formula did not appear to be effective for major operations.[16][18]

Formulation of tsūsensan

Hanaoka was intrigued when he learned about Hua Tuo's mafeisan potion. Beginning in about 1785, Hanaoka embarked on a quest to re-create a compound that would have pharmacologic properties similar to Hua Tuo's mafeisan.[1] His wife, who participated in his experiments as a volunteer, lost her sight due to adverse side effects. After years of research and experimentation, he finally developed a formula which he named tsūsensan (also known as mafutsu-san). Like that of Hua Tuo, this compound was composed of extracts of several different plants, including:[19][20][21]

- 8 parts yang jin hua (Datura stramonium, Korean morning glory, thorn apple, jimson weed, devil's trumpet, stinkweed, or locoweed);

- 2 parts bai zhi (Angelica dahurica);

- 2 parts cao wu (Aconitum sp., monkshood or wolfsbane);

- 2 parts chuān ban xia (Pinellia ternata);

- 2 parts chuān xiōng (Ligusticum wallichii, Cnidium rhizome, Cnidium officinale or Szechuan lovage);

- 2 parts dong quai (Angelica sinensis or female ginseng);

- 1 part tian nan xing (Arisaema rhizomatum or cobra lily).

Some sources claim that Angelica archangelica (often referred to as garden angelica, holy ghost, or wild celery) was also an ingredient.

Reportedly the mixture was ground to a paste, boiled in water, and administered as a drink. After 2 to 4 hours the patient would become insensitive to pain and then lapse into unconsciousness. Depending on the dosage, they might remain unconscious for 6–24 hours. The active ingredients in tsūsensan were scopolamine, hyoscyamine, atropine, aconitine and angelicotoxin. When consumed in sufficient quantity, tsūsensan produced a state of general anesthesia and skeletal muscle paralysis.[21]

Shutei Nakagawa (1773–1850), a close friend of Hanaoka, wrote a small pamphlet entitled "Mayaku-ko" ("narcotic powder") in 1796. Although the original manuscript was lost in a fire in 1867, this brochure described the current state of Hanaoka's research on general anesthesia.[5]

Use of tsūsensan as a general anesthetic

Once perfected, Hanaoka began to administer his new sedative drink to induce a state of consciousness equivalent to or approximating that of modern general anesthesia to his patients. Kan Aiya (藍屋勘) was a 60-year-old woman whose family was beset by breast cancer - Kan being the last of her kin alive. On 13 October 1804, Hanaoka performed a partial mastectomy for breast cancer on Kan Aiya, using tsūsensan as a general anesthetic. This is regarded today by some as the first reliable documentation of an operation to be performed under general anesthesia.[1][20][22][23] Nearly forty years would pass before Crawford Long used general anesthesia in Jefferson, Georgia.[24]

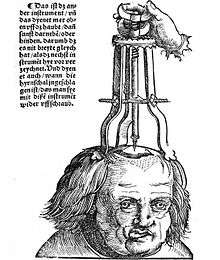

Hanaoka's success in performing this painless operation soon became widely known, and patients began to arrive from all parts of Japan. Hanaoka went on to perform many operations using tsūsensan, including resection of malignant tumors, extraction of bladder stones, and extremity amputations. Before his death in 1835, Hanaoka performed more than 150 operations for breast cancer.[1][23][25][26] He also devised and modified surgical instruments, and trained and educated many students, using his own philosophy for medical management. Hanaoka attracted many students, and his surgical techniques became known as the Hanaoka method.[1]

Publications

Hanaoka wrote the following works. It should be noted that none of these were printed books. Rather (as was the custom in Japan at that time), they were all handwritten manuscripts which were later reproduced by his students for their personal use.[6]

- 1805: Nyuigan chiken-roku, a one-volume book that provides a detailed description of Hanaoka's first operation for mammary carcinoma.

- 1805: Nyugan saijo shujutsu-zu, a one-volume book that provides a detailed description of Hanaoka's first operation for mammary carcinoma.

- 1809: Nyuigan zufu, an illustrated emakimono in one roll which also pictured breast cancer.

- 1820: Geka tekiyio, a one volume text.

- 1838: Hanaoka-ke chiken zumaki, an illustrated emakimono scroll depicting 86 different cases, including surgical resection of fibromas and elephantiasis of the genitalia.).

- Date unknown: Hanaoka-shi chijitsu zushiki, a one-volume illustrated book that depicts his operations for the treatment of conditions such as phimosis, arthritis, necrosis, choanal atresia, and hemorrhoids.

- Date unknown: Seishuiidan, a series of essays on Hanaoka's medical and surgical experiences.

- Date unknown: Yoka hosen, a one volume text.

- Date unknown: Yoka shinsho, a one volume text on surgery.

- Date unknown: Yoka sagen, a two volume text on surgery.

The surgical teachings of Hanaoka were also preserved in a series of eight handwritten books by unnamed pupils, but known to us by the following titles: Shoka shinsho, Shoka sagen, Kinso yojutsu, Kinso kuju, Geka chakuyo, Choso benmei, Nyuiganben, and Koho benran. No dates are known for any of these writings. Since Hanaoka himself made only manuscript copies and none were ever published, it is doubtful if many copies of his surgical writings are now extant.[6]

Legacy

Though some of his patients are said to have benefited from Hanaoka's work, it apparently had no impact upon the development of general anesthesia in the rest of the world. The national isolation policy of the Tokugawa shogunate prevented Hanaoka's achievements from being publicized until after the isolation ended in 1854. By that time, different techniques for general anesthesia had already been independently developed by American and European scientists and physicians. The Japan Society of Anesthesiologists however has incorporated a representation of the Korean morning glory flower in their logo in honor of Hanaoka's pioneering work.

Hanaoka's house has been preserved in his hometown (Naga-cho, Kinokawa, Wakayama). It has various interactive exhibits in both Japanese and English. It is adjacent to a nursing college, and many locally trained doctors and nurses pay homage to Hanaoka and his works.

Popular culture

The Japanese author Sawako Ariyoshi wrote a novel entitled, The Doctor's Wife (Japanese 華岡青洲の妻), based on the actual life of Hanaoka Seishū mixed with a fictional conflict between his mother and his wife. The novel was subsequently filmed as a 1967 movie directed by Yasuzo Masumura, Hanaoka Seishū no tsuma (aka "The Wife of Seishu Hanaoka").

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Izuo M (2004). "Medical history: Seishū Hanaoka and his success in breast cancer surgery under general anesthesia two hundred years ago". Breast Cancer. 11 (4): 319–24. doi:10.1007/BF02968037. PMID 15604985. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- ↑ Mestler GE (1956). "A galaxy of old Japanese medical books with miscellaneous notes on early medicine in Japan. IV. Ophthalmology, psychiatry, dentistry". Bull Med Libr Assoc. 44 (3): 327–47. PMC 200027

. PMID 13342674.

. PMID 13342674. - ↑ Mestler GE (1954). "A Galaxy of Old Japanese Medical Books with Miscellaneous Notes on Early Medicine in Japan Part I. Medical History and Biography. General Works. Anatomy. Physiology and Pharmacology". Bull Med Libr Assoc. 42 (3): 287–327. PMC 199727

. PMID 13172583.

. PMID 13172583. - ↑ Mestler GE (1957). "A galaxy of old Japanese medical books with miscellaneous notes on early medicine in Japan. Part V: biblio-historical addenda, corrections, postscript, acknowledgments". Bull Med Libr Assoc. 45 (2): 164–219. PMC 200108

. PMID 13413448.

. PMID 13413448. - 1 2 Matsuki A (1999). "A bibliographical study on Shutei Nakagawa's "Mayaku-ko" (a collection of anesthetics and analgesics)--a comparism of four manuscripts". Nihon Ishigaku Zasshi (Journal of the Japanese Society for Medical History) (in Japanese). 45 (4): 585–99. ISSN 0549-3323. PMID 11624281. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mestler GE (1956). "A galaxy of old Japanese medical books with miscellaneous notes on early medicine in Japan. Part III.: urology, syphilology and dermatology; surgery and pathology". Bull Med Libr Assoc. 44 (2): 125–59. PMC 199999

. PMID 13304528.

. PMID 13304528. - ↑ Toby RP (1977). "Reopening the Question of Sakoku: Diplomacy in the Legitimation of the Tokugawa Bakufu". Journal of Japanese Studies. 3 (2): 323–63. doi:10.2307/132115. JSTOR 132115.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chu NS (2004). "Legendary Hwa Tuo's surgery under general anesthesia in the second century China" (PDF). Acta Neurol Taiwan (in Chinese). 13 (4): 211–6. ISSN 1028-768X. PMID 15666698. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- 1 2 Giles HA (1898). A Chinese Biographical Dictionary. London: Bernard Quaritch. pp. 323–4, 762–3. Retrieved 2010-09-14.

If a disease seemed beyond the reach of needles and cautery, he operated, giving his patients a dose of hashish which rendered them unconscious.

- 1 2 Giles L (transl.) (1948). Cranmer-Byng JL, ed. A Gallery of Chinese immortals: selected biographies, translated from Chinese sources by Lionel Giles (Wisdom of the East series) (1 ed.). London: John Murray. Retrieved 2010-09-14.

The well-attested fact that Hua T'o made use of an anaesthetic for surgical operations over 1,600 years before Sir James Simpson certainly places him to our eyes on a pinnacle of fame....

- 1 2 Chen J (2008). "A Brief Biography of Hua Tuo". Acupuncture Today. 9 (8). ISSN 1526-7784. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- ↑ Wang Z; Ping C (1999). "Well-known medical scientists: Hua Tuo". In Ping C. History and Development of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 1. Beijing: Science Press. pp. 88–93. ISBN 7-03-006567-0. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- ↑ Fu LK (2002). "Hua Tuo, the Chinese god of surgery". J Med Biogr. 10 (3): 160–6. PMID 12114950. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- ↑ Gordon BL (1949). Medicine throughout Antiquity (1 ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company. pp. 358, 379, 385, 387. OCLC 1574261. Retrieved 2010-09-14.

Pien Chiao (ca. 300 BC) used general anesthesia for surgical procedures. It is recorded that he gave two men, named "Lu" and "Chao", a toxic drink which rendered them unconscious for three days, during which time he performed a gastrotomy upon them

- ↑ Huang Ti Nei Ching Su Wen: The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine. Translated by Ilza Veith. Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press. 1972. ISBN 0-520-02158-4.

- 1 2 Ch'en S (2000). "The Biography of Hua-t'o from the History of the Three Kingdoms". In Mair VH. The shorter Columbia anthology of traditional Chinese literature. Part III: Prose. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 441–9. ISBN 0-231-11998-4. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- ↑ Lu GD; Needham J (2002). "Acupuncture and major surgery". Celestial lancets: a history and rationale of acupuncture and moxa. London: RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 218–30. ISBN 0-7007-1458-8. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- ↑ Wai FK (2004). "On Hua Tuo's Position in the History of Chinese Medicine". The American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 32 (2): 313–20. doi:10.1142/S0192415X04001965. PMID 15315268. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- ↑ Ogata T (1973). "Seishu Hanaoka and his anaesthesiology and surgery". Anaesthesia. 28 (6): 645–52. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1973.tb00549.x. PMID 4586362.

- 1 2 Hyodo M (1992). "Doctor S. Hanaoka, the world's-first success in providing general anesthesia". In Hyodo M, Oyama T, Swerdlow M. The Pain Clinic IV: proceedings of the fourth international symposium. Utrecht, Netherlands: VSP. pp. 3–12. ISBN 90-6764-147-2. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- 1 2 van D. JH (2010). "Chosen-asagao and the recipe for Hanaoka's anesthetic 'tsusensan'". Brighton, UK: BLTC Research. Retrieved 2010-09-13. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Perrin, N (1979). Giving up the gun: Japan's reversion to the sword, 1543-1879. Boston: David R. Godine. p. 86. ISBN 0-87923-773-2. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- 1 2 Matsuki A (2000). "New studies on the history of anesthesiology--a new study on Seishū Hanaoka's "Nyugan Ckiken Roku" (a surgical experience with breast cancer)". Masui: the Japanese Journal of Anesthesiology. 49 (9): 1038–43. ISSN 0021-4892. PMID 11025965. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- ↑ Long CW (1849). "An account of the first use of Sulphuric Ether by Inhalation as an Anaesthetic in Surgical Operations". Southern Medical and Surgical Journal. 5: 705–13. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- ↑ Tominaga T (1994). "Presidential address: Newly established Japanese breast cancer society and the future". Breast Cancer. 1 (2): 69–78. doi:10.1007/BF02967035. PMID 11091513. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- ↑ Matsuki A (2002). "A Study on Seishu Hanaoka's Nyugan Seimei Roku (Scroll of Diseases): A Name List of Breast Cancer Patients". Nihon Ishigaku Zasshi (Journal of the Japanese Society for Medical History) (in Japanese). 48 (1): 53–65. ISSN 0549-3323. PMID 12152628. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

External links

- Turning the Pages: a virtual reconstruction of Hanaoka's Surgical Casebook, ca. 1825. From the U.S. National Library of Medicine.