Hasidic philosophy

Hasidic philosophy or Hasidus (Hebrew: חסידות), alternatively transliterated as Hassidism, Chassidism, Chassidut etc. is the teachings, interpretations, and practice of Judaism as articulated by the Hasidic movement. Thus, Hasidus is a framing term for the teachings of the Hasidic masters, expressed in its range from Torah (the Five books of Moses) to Kabbalah (Jewish mysticisim). Hasidus deals with a range of spiritual concepts such as God, the soul, and the Torah, and gives them understandable, applicable and practical expressions.[2][3] It also discusses the charismatic religious elements of the movement, but mainly Hasidus describes the structured thought and philosophy of Hasidim. In other words, it speaks of the "soul of Torah", as Hasidus is often referred to by that very name.[4]

"Hasidus" (piousness) and "Hasid" (a pious person) are terms used in Jewish literature of all ages, and are not limited to adherents of the Hasidic movement, whose philosophy is discussed in this article.

The term "Hasidus"

The word derives from the Jewish spiritual term Hessed (or "Chessed"), commonly translated as "loving-kindness," and which also means kindness, love and merciful behavior. It is also one of the 10 Sephirot of Kabbalah, which represents God's provision of good and sustenance to the world, and the power underlying similar actions performed by human beings. The word "Hasidus," sometimes pronounced "Hasidut", as well as its appellation "hasid",[5] has been used in Jewish tradition for pious persons who have sincere motives in serving God and helping others, especially when not obligated to do so ("lifenim mi-shurat ha-din"). The "Hasid" goes above and beyond what is demanded of him by ordinary morality and the boundaries of Halakha, the collective body of religious laws for Jews which derive from the Torah.

In Jewish religious practice, "Middat hasidut" is a religious observance or moral practice which goes beyond mere obedience to Halakha, it is an extraordinary act of good performed by an individual because of their love for a fellow person or for God. An early mention of the term "middat hasidut" appears in the Talmud (Baba Metzia 52:2), and thereafter it was used widely in Jewish Halakhic literature. Thus the term "hasid" should not be mistaken to refer solely to a follower of the Eastern European movement started by the Baal Shem Tov in the 18th century and its philosophy known as hasidus. Rather, "hasid" is a title used for many pious individuals and by many Jewish groups since Biblical times.[6] Some earlier European Jewish movements were also called by this name, such as the Hasidei Ashkenaz of medieval Germany.[6]

Today, however, the terms hasidus and hasid generally connote Hasidic philosophy and the followers of the Hasidic movement.[2][4] They refer to the mystical, populist revival of Judaism, initiated by Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer (the Baal Shem Tov) in 18th century Podolia and Volhynia (now Ukraine). His close disciples developed the philosophy in the early years of the movement. From the third generation, the select leadership mutually decided to split the Hasidic movement into smaller groups with the hope of more easily spreading hasidus across Eastern Europe. These new leaders, who until now were all adherents of the second generation leader, settled in cities from Poland, Hungary and Romania, to Lithuania and Russia.[5]

In general

Hasidic tradition and thought has gained admirers[2][5] from outside its immediate following, and outside Orthodox Jewish belief, for its charismatic inspiration and kabbalistic insights. "Ḥasidism should in Jewish history be classed among the most momentous spiritual revolutions that have influenced the social life of the Jews, particularly those of eastern Europe."[5]

Distilling a culture of Jewish religious life that began before the arrival of modernity, its stories, anecdotes, and creative teachings have offered spiritual dimensions for people today. In its more systematic and intellectual articulations, however, it is also a form of traditional Jewish interpretation (exegesis) of Scriptural and Rabbinic texts, a new stage in the development of Jewish mysticism, and a philosophically illuminated system of theology that can be contrasted with earlier, mainstream Jewish Philosophy. This quality can bridge and unite the different disciplines of philosophy and mysticism[5] (in the older Jewish tradition of Kabbalah, experiential connection with spirituality takes place through a highly elaborate conceptual theology and textual interpretation, in contrast with some common, more intuitive definitions of mysticism; new ideas derive authority from Scriptural interpretation, and therefore gain an intellectual organisation). Hasidic thought builds upon Kabbalah,[5] and is sometimes called a new stage in its development. However, this generalisation is misleading (although implicit in Hasidus are new interpretations of Kabbalah, that can be drawn out and related to its new philosophical positions). Kabbalah gives the complete structure of traditional Jewish metaphysics, using subtle categorisations and metaphors. This studies the Divine interaction with Creation, through describing the emanations that reveal, and mediate Godliness. Because of the concern to divest these ideas from any physical connotations, Kabbalists traditionally restricted their transmission to closed circles of advanced scholars, for fear of misinterpreting sensitive concepts. Hasidus leaves aside the Kabbalistic focus on complicated metaphysical emanations, to look at the simple essence of Divinity that it sees permeating within each level, and transcending all. Hasidus looks to the inner spiritual meaning within Kabbalah by relating its ideas to man's inner psychological awareness, and conceptual analogies from man's observation. This independence from the esoteric nature of Kabbalah, gives Hasidic thought its ability to be expressed in its spiritual stories, tangible teachings, and emotional practices, as well as the ability to pervade and illuminate other levels of Torah interpretation, not only the hidden ideas of Kabbalah. Hasidus only utilises Kabbalistic terminology when it explains and enlivens the Kabbalistic level of Torah interpretation. This distinctive ability to bring Kabbalah into intellectual and emotional grasp, is only one of the characteristics and forms of Hasidic thought. The more involved Hasidic writings use Kabbalah extensively, according to their alternative paths within Hasidism, but only as a means to describe the inner processes of spirituality, as they relate to man's devotional life. The spiritual contribution of the range of Hasidus avoids the concerns that traditionally restricted Kabbalah, and for the first time,[5] offered the whole population access to the inner dimensions of Judaism.

Overview in historical context

The new interpretations of Judaism initiated by the Baal Shem Tov, and developed by his successors, took ideas from across Jewish tradition, and gave them new life and meaning. It especially built upon the mystical tradition of Kabbalah, and presented it in a way that was accessible for the first time by all Jews. Until then the Jewish mystical tradition had only been understandable and reserved for a scholarly elite. The innovative spirituality of Hasidism, sought to leave aside the advanced and subtle metaphysical focus of Kabbalah on the Heavenly Spiritual Worlds, to apply the Kabbalistic theology to the everyday life. The new teachings centered on Divine immanence present in all of Creation, and an experience of Divine love and meaningful purpose behind every occurrence of daily life.

The Baal Shem Tov and his successors, offered the masses a new approach to Judaism, that valued sincerity and emotional fervour. This was conveyed through inner mystical interpretations of Scripture and Rabbinic texts, sometimes conveyed by imaginative parables, as well as hagiographic tales about the Hasidic Masters, and new dimensions to melody (Nigun) and customs (Minhag). The Baal Shem Tov taught by means of parables and short, heartwarming Torah explanations that encapsulated profound interpretations of Jewish mysticism. The unlearned, downtrodden masses were captivated by this new soul and life breathed into Judaism, while the select group of great disciples around the Baal Shem Tov, could appreciate the scholarly and philosophical significance of these new ideas. The anecdotal stories about the legendary figures of Hasidism, offered a vivid bridge between the intellectual ideas, and the spiritual, emotional enthusiasm they inspired. Implicit in Hasidic tales are the new doctrines of Hasidism, as the new interpretations of Torah taught by its leaders, were also lived in all facets of their life and leadership, and their new paths to serving God. This gave birth to new Jewish practices in the lives of their followers that also reflected the new teachings of the movement.

Each school of Hasidic thought adopted different approaches and interpretations of Hasidism. Some put primary emphasis on the new practices and customs ("Darkei Hasidus"-the Ways of Hasidus) that encouraged emotional enthusiasm, and attached the followers to the holy influence of their leaders, and some put their main emphasis on scholarly learning of the Hasidic teachings of their leaders ("Limmud Hasidus"-the Learning of Hasidus). Some groups have seen the Hasidic way as an added warmth to a more mainstream Jewish observance, while others have placed the learning of the writings of their school, on a more comparable level to learning the esoteric parts of Judaism. These differences are reflected in different styles of Hasidic thought.

This diversity mirrors the historic development of Hasidism. From late Medieval times, Central and Eastern European Kabbalistic figures called Baal Shem encouraged the influence of Jewish mysticism, through groups of Nistarim (Hidden mystics). With the teaching of the Baal Shem Tov (1698–1760), centred on Podolia (Ukraine), the new ideas of Hasidism were conveyed initially in emotional forms. After his death, his great disciples appointed Dov Ber of Mezeritch (1700?–1772) (The Maggid of Mezeritch) to succeed him. Under the leadership of the Maggid, the new movement was consolidated, and the teachings explained and developed. The Baal Shem Tov was a leader for the people, travelling around with his saintly followers, bringing encouragement and comfort to the simple masses. Dov Ber, whose ill health prevented him from travel, devoted his main focus to developing around himself a close circle of great, scholarly followers (called the "Hevra Kaddisha"-Holy Society) who were to become the individual leaders of the next generation, appointed different territories across Jewish Eastern Europe to spread Hasidism to. They formed different interpretations of Hasidic thought, from profound insight in mystical psychology, to philosophical intellectual articulations. Many of the Hasidic leaders of the third generation, occupy revered places in Hasidic history, or influenced subsequent schools of thought. Among them are Elimelech of Lizhensk, who fully developed the Hasidic doctrine of the Tzaddik (mystical leader) that gave birth to many Polish Rebbes, and his charismatic brother Meshulam Zushya of Anipoli. Levi Yitzchok of Berditchev became the renowned defender of the people before the Heavenly Court, while Shneur Zalman of Liadi initiated the Habad school of intellectual Hasidism. Subsequent Hasidic leaders include Nachman of Breslav, Menachem Mendel of Kotzk.

Characteristic ideas

Conduct

- Dveikut: Hasidism teaches that dveikut (Hebrew: דביקות-bonding), or bonding with God, is the highest form of God's service and the ultimate goal of all Torah study, prayer, and fulfilling the 613 Mitzvot. The highest level of dveikut is Hitpashtut Hagashmiut (Hebrew: התפשטות הגשמיות), which is an elevated state of consciousness in which the soul divests itself of the physical senses of the body and attains a direct perception of the Divine in all things. The very act of striving toward dveikut is meant to elevate one's spiritual awareness and sensitivity, and to add life, vigor, happiness and joy to one's religious observance and daily actions.

- Godliness in all Matter: Hasidism emphasises the previous Jewish mystical idea to extract and elevate the Divine in all material things, both animate and inanimate. As taught in earlier Kabbalistic teachings from Isaac Luria, all worldly matter is imbued with nitzotzot (Hebrew: ניצוצות), or Divine sparks, which were disseminated through the "Breaking of the Vessels" (in Hebrew: שבירת הכלים), brought about through cosmic processes at the beginning of Creation. The Hasidic follower strives to elevate the sparks in all those material things that aid one's prayer, Torah study, religious commandments, and overall service of God. A related concept is the imperative to engage with the Divine through mundane acts, such as eating, sexual relations, and other day-to-day activities. Hasidism teaches that all actions can be utilized for the service of God when fulfilled with such intent. Eating can be elevated through reciting the proper blessings before and after, while maintaining the act's intent as that of keeping the body healthy for the continued service of God. Sexual relations can be elevated by abstaining from excessive pursuits of sexual pleasures, while maintaining focus on its core purposes in Jewish thought: procreation, as well as the independent purpose of deepening the love and bond between husband and wife, two positive commandments. Business transactions too, when conducted within the parameters of Jewish law and for the sake of monetary gain that will then be used for fulfilling commandments, serve a righteous purpose.

- Joy: Hasidism emphasizes joy as a precondition to elevated spiritual awareness, and teaches the avoidance of melancholy at all costs. For the same reason, Hasidism shunned the earlier practices of asceticism known to Kabbalists and Ethical followers, as having the potential to induce downheartedness and a weaker spirit for God's service. Nonetheless, the Hasidic masters themselves would often privately follow ascetic practices, as they could adopt such conduct without fear that it would damage their Jewish observance. This was not intended as an example for the followers.

- Bonding with the Tzadik: Hasidism teaches that while not all are able to attain the highest levels of elevated spirituality, the masses can attach themselves to the Tzadik, or truly righteous one, (in Hebrew: התקשרות לצדיקים) whereby even those of lesser achievement will reap the same spiritual and material benefits. By being in the Tzadik's presence, one could achieve dveikut through that of the Tzadik. The Tzadik also serves as the intercessor between those attached to him and God, and acts as the channel through which Divine bounty is passed. To the early Rabbinic opponents of Hasidism, its distinctive doctrine of the Tzadik appeared to place an intermediary before Judaism's direct connection with God. They saw the Hasidic enthusiasm of telling semi-prophetic or miraculous stories of its leaders as excessive. In Hasidic thought, based on earlier Kabbalistic ideas of collective souls, the Tzaddik is a general soul in which the followers are included. The Tzaddik is described as an "intermediary who connects" with God, rather than the heretical notion of an "intermediary who separates". To the followers, the Tzaddik is not an object of prayer, as he attains his level only by being completely bittul (nullified) to God. The Hasidic followers have the custom of handing pidyon requests for blessing to the Tzaddik, or visiting the Ohel graves of earlier leaders. The radical statements of the power of the Tzaddik, as the channel of Divine blessing in this world through which God works, are based on a long heritage of Kabbalistic, Talmudic and Midrashic sources. The beloved and holy status of the Tzaddik in Hasidism elevated storytelling about the Masters into a form of dveikut:

One Hasidic Master related that he visited the court of Dov Ber of Mezeritch to "see how he tied his shoelaces"[7]

Schools of thought

With the spread of Hasidism throughout Ukraine, Galicia, Poland, and Russia, divergent schools emerged within Hasidism. Some schools place more stress on intellectual understanding of the Divine, others on the emotional connection with the Divine. Some schools stress specific traits or exhibit behavior not common to other schools.

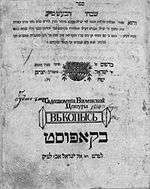

Notable works

Among the major tracts compiled by early Hasidic masters are:

- Toldos Yakov Yosef, by Jacob Joseph of Polnoye (1780)

- Magid Devarav L'yakov, by Dovber of Mezritch, compiled by Shlomo of Lutzk (1781)

- Noam Elimelech, by Elimelech of Lizhensk (1788)

- Likutei Amarim (Tanya), by Shneur Zalman of Liadi (1796)

- Kedushas Levi, by Levi Yitzchok of Berditchev (1798)

- Meor Einayim, by Menachem Nachum Twerski of Chernobyl (1798)

- Likutei Moharan, by Nachman of Breslov (1808)

- Siduro Shel Shabbos, by Hayyim Tyrer (1813)

- Shivchei HaBesht, by Dov Ber Schochet (1815)

- Sippurei Ma'asiot by Nachman of Breslov (1816)

See also

Bibliography

- The Great Mission – The Life and Story of Rabbi Yisrael Baal Shem Tov,Compiler Eli Friedman, Translator Elchonon Lesches, Kehot Publication Society.

- The Great Maggid – The Life and Teachings of Rabbi DovBer of Mezhirech, Jacob Immanuel Schochet, Kehot Publication Society.

- The Hasidic Tale, Edited by Gedaliah Nigal, Translated by Edward Levin, The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization.

- The Hasidic Parable, Aryeh Wineman, Jewish Publication Society.

- The Religious Thought of Hasidism: Text and Commentary,Edited by Norman Lamm, Michael Scharf Publication Trust of Yeshiva University.

- Hasidism: The Movement and its Masters, Harry Rabinowicz, Jason Aronson.

- Wrapped in a Holy Flame: Teachings and Tales of The Hasidic Masters, Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, Jossey-Bass.

- The Zaddik: The Doctrine of the Zaddik According to the Writings of Rabbi Yaakov Yosef of Polnoy, Samuel H. Dresner, Jason Aronson publishers.

- Communicating the Infinite: The Emergence of the Habad School, Naftali Loewenthal, University of Chicago Press.

- Tormented Master: The Life and Spiritual Quest of Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav, Arthur Green, Jewish Lights Publishing.

- A Passion for Truth, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Jewish Lights Publishing.

- Tales of the Hasidim (vol.1 The Early Masters, vol.2 The Later Masters, here published together), Martin Buber, Schocken.

- Lubavitcher Rabbi's Memoirs: Tracing the Origins of the Chasidic Movement – vol.1,2, Yoseph Yitzchak Schneersohn, Translated by Nissan Mindel, Kehot Publication Society.

- Souls on Fire – Portraits and Legends of Hasidic Masters, Elie Wiesel, Simon & Schuster.

- The Earth is the Lord's: The Inner World of the Jew in Eastern Europe, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Jewish Lights Publishing.

- Rabbi Nachman's Stories, translated by Aryeh Kaplan, Breslov Research Institute publication.

- On the Essence of Chassidus, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, translated by Y.Greenberg and S.S.Handelman, Kehot Publication Society.

- Hasidism Reappraised, Edited by Ada Rapoport-Albert, Littman Library of Jewish Civilization.

- The Mystical Origins of Hasidism, Rachel Elior, Littman Library of Jewish Civilization.

- Hasidic Prayer, Louis Jacobs, Littman Library of Jewish Civilization.

Notes

- ↑ Letter from Rabbi Yisrael Baal Shem Tov to his brother in-law Abraham Gershon of Kitov

- 1 2 3 Freeman, Tzvi. "What is Chassidut". Learning and Values. Chabad-Lubavitch Media Center. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ↑ Ginsburgh, Rabbi Yitzchok. "What is Chassidut (Chassidic Philosophy)". AskMoses.com © 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- 1 2 Chein, Rabbi Shlomo. "If Chassidut is so important, why wasn't it available until 300 years ago?". Chassidism. AskMoses.com © 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "?ASIDIM - ?ASIDISM". The unedited full-text of the 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia. JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- 1 2 "?asidut - SAINT AND SAINTLINESS". The unedited full-text of the 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia. JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ↑ Cited in The Great Maggid by Jacob Immanuel Schochet. Kehot Publications