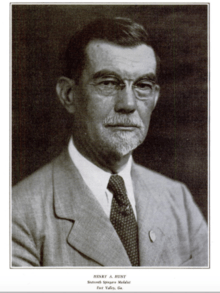

Henry A. Hunt

Henry Alexander Hunt (October 10, 1866[2] – October 1, 1938) was an African-American educator who led efforts to reach blacks in rural areas of Georgia. He was awarded the Spingarn Medal by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), as well as the Harmon Prize. In addition, he was recruited in the 1930s by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to join the president's Black Cabinet, a group of more than 40 prominent African Americans appointed to positions in the executive agencies.

Early life

Henry A. Hunt was born on October 10, 1866 to parents Henry Alexander Hunt, Sr. and Mariah Hunt.[3] He was born on "Hunt Hill", by the small town of Sparta, in Hancock County, Georgia, part of the Black Belt. Hunt was the youngest of eight mixed-race children, four boys and four girls, born to an African American mother, Mariah Hunt. The Hunts lived in a weather-beaten house on their small farm and the children grew up working on the farm.[4] Despite his African American roots, Hunt's appearance led people to assume he was from purely Caucasian descent. After Henry Hunt's death, W.E.B. Du Bois, a personal friend of his, publicly spoke of Henry's Caucasian appearance and reflected on the questions Hunt received about why he did not choose to hide his mixed-race background.[5]

Education

He attended school at Sparta for his early education. In 1882, at the age of 16, he started at Atlanta University, one of the historically black colleges created after the American Civil War.[6] While attending Atlanta University, Hunt met Florence Johnson, the woman he would eventually marry in 1893.[6][7] E. A. Johnson, Florence's brother, was the former Assemblyman of New York.[8] Throughout his time as a college student, including vacations from school, Hunt worked as a carpenter to earn money.[9] Hunt graduated from Atlanta University with a Bachelors of Arts degree and completion of coursework in the Industrial Department in 1890.[4][6]

Career

Early career

Hunt worked for the education of black students for his entire career. After graduating, he had a job offer in Africa, but he turned this down to be the principal at Charlotte Grade School in Charlotte, North Carolina.[4] Henry Hunt stayed at this position for less than a year, leaving the Charlotte Grade School in 1891 for the position of Superintendent of the Industrial Department at Biddle University (now Johnson C. Smith University). In the year 1900, Hunt established an annual African American farmer's conference including the counties surrounding Charlotte, North Carolina.[6] Henry Hunt continued to work for Biddle University for the rest of the thirteen and a half years the Hunts were in Charlotte, North Carolina.[4] By the time he left Biddle University, he had also been appointed as Superintendent of Boarding.[9]

Fort Valley Career

He was then the principal of Fort Valley High and Industrial School, Fort Valley, Georgia.[8] [10] The Fort Valley High and Industrial School, affiliated with the American Church Institute of the Protestant Episcopal Church, was chartered in 1895, but struggled financially.[11] The school received funds from Northern philanthropists, but there were disagreements about whether the school should pursue a Liberal Arts educational model or the Hampton-Tuskegee Industrial educational model.[9] In the 1902-1903 school year, the school's first principal, John W. Davis was released as principal and the trustees began looking for replacements.[9] George Foster Peabody, one of Fort Valley's Northern philantrhopists who was on the Board of Trustees, suggested Henry Alexander Hunt because of his work at Biddle University. Other trustees had suggested different men for the position of principal and although Henry Hunt was among the final three candidates, he was only offered the position after the other two men had declined the job.

Even after this, Hunt did not immediately get the job. The trustees were reluctant to hire an Atlanta University graduate since Booker T. Washington had advised the Board of Trustees that an Industrial College not run by a Hampton or Tuskegee graduate, was not likely to be successful.[9] The 1903 school year began for Fort Valley High and Industrial School began without a principal as the trustees continued to scrutinize Hunt. Hunt stressed the mechanical background he acquired from his industrial studies at Atlanta University and his background in carpentry and was then hired in November 1903.[9] The Hunts moved to Fort Valley with their three small children, two girls and one boy, and Hunt began his career as the Fort Valley High and Industrial School principal on February 9, 1904.[4][9]

When the Hunts came to the school it consisted of a single building, Odd Fellows Lodge, and the school had an annual budget of $840.[4][7] The Hunts lived with no running water.[7] Hunt began to change the school's educational model to aim more towards vocational training and trade-based studies.[4] Hunt instated classes in sewing, cooking, carpentry, and gardening. Hunt also planted two hundred peach trees (Fort Valley is located in what is known as the Peach Belt) to expand the agricultural program to include practical and demonstrative agricultural education.[9] Hunt felt a focus on agricultural studies was important given the emphasis on and prevalence of agriculture in middle Georgia, where the school was located. In the beginning and throughout Hunt's career the area surrounding the school was dominated by a population of African Americans who worked in agriculture. Hunt often stated his goal as empowering the African Americans attending Fort Valley, as well as the surrounding African American community, to become effective in their trade.[9]

"With Negroes cultivating millions of acres of land, surely no argument is needed to prove the wisdom and the justice of giving them every possible opportunity to learn how to do that work more intelligently and with greater skill." [4]

In 1907, Hunt presented to the Board of Trustees the need to add the study of scientific agricultural training to the existing agricultural studies program.

"Working as we do among a people who are engaged very largely in agriculture it would seem to be not only important but absolutely necessary that special inducements be held out to students who wish to give attention to this particular line of work."[4]

Also in 1907, Hunt began an annual Fort Valley conference for African American farmers. The conference brought experts from throughout the state, the country and some of the top industrial schools such as Tuskegee, to inform the attendees of the latest agricultural technology and information. At these conferences, Hunt stressed the possibility for African American farmers to own their farms.[4] In 1907, Hunt also began a practical agricultural program, with the help of the United States Department of Agriculture, five acres of land were cultivated and used as part of the educational process through demonstrations.[4] With financial help from the General Board of Education, Hunt added fifty-five acres to the school’s educational farmland in 1915.[9] Hunt’s reputation as an advocate for the African American farmer spread. In 1918, the Governor of Georgia, Hugh M. Dorsey, appointed Hunt to the position of supervisor of Negro economics for the state of Georgia. In this position Hunt focused on problems relating to agricultural labor in Georgia.[4]

In 1925, W.E.B. Du Bois asked for Hunt's help with a research project focused on the study of Negro Common Schools in Georgia. In a response letter to Du Bois, Hunt expressed interest but ultimately declined the offer because he was busy overseeing the building of a boy's dormitory on the Fort Valley campus.[12]

In 1930, Henry Hunt was awarded the 16th Spingarn Medal for his 25 years of work in Fort Valley. When Henry Hunt started working for Fort Valley High and Industrial School there was only one building. Over the years, he raised funds to build the plant of the school and turned it into a community center of teaching about health and farming, as well as academic subjects, and built relations with the regional community of 300,000 blacks and whites. The result of this was a campus expanded to 12 buildings, 91 acres of land, and a worth of $450,000 in 1930.[8] In 1931 Hunt received the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship, which came with $1,400 and the purpose of travelling to Scandinavian countries to study agriculture and cooperatives.[4]

In 1939 Fort Valley High and Industrial School was consolidated with the Teacher College and became Fort Valley College. With expansion and addition of programs, in 1996, it became chartered as Fort Valley University.

Farm Credit Administration

Under Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Deal, many administrations and committees were created. One such administration was the Farm Credit Administration, (originally named the Federal Farm Board), which had the purpose of providing governmental support to farmers. Henry Morgenthau Jr. was appointed as governor of the Farm Credit Administration. Morgenthau wanted an African American man to assist him with his work, and in particular, spread awareness of the administration throughout the African American farming population.[5] Henry Hunt moved to Washington D.C. to fulfill the position of Assistant Governor of the Farm Credit Administration in November 1933.[4] Hunt maintained his position as principal of Fort Valley High and Industrial School, and Florence remained in Fort Valley to attend to the school.[13] As Assistant Governor of the Farm Credit Administration, Hunt travelled often to connect with African American farmers and inform them of credit unions. A memorandum from Henry A. Hunt’s office in Washington D.C. summarizes some of Hunt’s research goals while holding the position in the Farm Credit Administration:

“To publicize the work and service of the Farm Credit Administration among Negro farmers in the United States, and to answer letters of inquiry from Negro farmers on all phases of Farm Credit Administration service, explaining to them the procedure involved in applying for credit through the various lending agencies operating under the supervision of the Farm Credit Administration. Also to act as an organizing agent for the Credit Union Section by meeting eligible groups of Negroes, explaining to them the aims and methods of the Federal Credit Act, and assisting in the preliminary steps for establishing credit unions.”[4]

On November 22, 1933, shortly after his appointment to Assistant Governor of the Farm Credit Administration, Hunt wrote a letter to W.E.B. Du Bois, a personal friend of Hunt’s for more than 25 years of his life.[5] In this letter Hunt expresses gratitude to Du Bois for Du Bois’s recommendation of Hunt to Morgenthau. Even so, soon after his appointment, Hunt had already been writing letters to various institutions and administrations across the nation involved in the improvement of African American farmers’ lives.[14]

On February 7, 1934, Hunt was called to attend the Interdepartmental Group Concerned with Special Problems of Negroes, colloquially known as Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Black Cabinet.[15] He was one of a total of 45 African Americans who created federal policy on education, jobs and housing at major cabinet-level agencies in the executive branch. They also acted as Roosevelt's informal advisers on national issues related to African Americans and the New Deal. In 1935, a sub-committee of this Interdepartmental Group Concerned with Special Problems of Negroes, specifically dedicated to agriculture was formed of Hunt and four other men.[4]

Henry A. Hunt has also been credited as largely responsible for the creation of Flint River Farms, which was established in Macon County, Georgia in 1937.[4][16] The Flint River Farms was founded as a cooperative community for African American farmers.[4]

Hunt died on October 1, 1938[13]

Legacy and honors

- 1930 - Spingarn Medal

- In 1930, Hunt received the recognition of major awards for his twenty-five years of service in the education of black students.

- 1930 - Harmon Award - William E. Harmon Foundation award for distinguished achievement among Negroes, for education

References

- ↑ Horne, Frank. "The Crisis Magazine". Retrieved May 25, 2016.

- ↑ Passport Applications, Hancock County, GA - NARA Microfilm Publication M1490, 2740 rolls. General Records of the Department of State, Record Group 59. National Archives, Washington, D. C.

- ↑ Cothran, John C. (2006). A Search of African American Life, Achievement and Culture: First Search. Stardate Publishing. p. 111. ISBN 0963400207.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Bellamy, Donnie D. (1975). "Henry A. Hunt and Black Agricultural Leadership in the New South". The Journal of Negro History. JSTOR 2717018.

- 1 2 3 Du Bois, W.E.B. (October 10, 1940). "The Significance of Henry Hunt". W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Culp, Daniel Wallace (1902). Twentieth century Negro literature; or, A cyclopedia of thought on the vital topics relating to the American Negro. Atlanta: J.L. Nichols & Co. p. 394.

- 1 2 3 van Hartesveldt, PhD, Fred (February 13, 2015). "Florence Johnson: Wife of Second Principal Henry A. Hunt". Fort Valley State University Review. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Horne, Frank. "Henry A. Hunt, Sixteenth Spingarn Medalist", The Crisis, August 1930, p. 261

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Anderson, James D. (1988). The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 123–131. ISBN 0807842214.

- ↑ "Spingarn Medal Winners", National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (2009)

- ↑ Dumbuya, PhD, Peter (14 February 2005). "A Brief History of Fort Valley State University". Fort Valley State University Review. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ↑ Hunt, Henry A. (April 4, 1925). "Letter from Henry A. Hunt to W.E.B. Du Bois". W.E.B. Du Bois Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

- 1 2 http://www.fvsu.edu/about/history accessed December 15, 2010

- ↑ Hunt, Henry A. (November 22, 1933). "Letter from Henry A. Hunt to W.E.B. Du Bois". W.E.B. Du Bois Papers, Special Collection and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Library. Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- ↑ Kirby, John B. (1982). Black Americans in the Roosevelt Era: Liberalism and Race. 0870493493: University of Tennessee Press. p. 24.

- ↑ Hargrove, PhD., Pace, Zabawa, PhD., Tasha M., Michelle, Robert. "History". Flint River Farms. Retrieved May 25, 2015.