Hermann-Paul

| René Georges Hermann-Paul | |

|---|---|

.jpg) René Georges Hermann-Paul | |

| Born |

December 27, 1864 Paris |

| Died |

June 23, 1940 (aged 75) Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Artist and Illustrator |

René Georges Hermann-Paul (December 27, 1864 – June 23, 1940) was a French artist. He was born in Paris and died in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer.

Recent efforts to catalog the work of Hermann-Paul reveal an artist of considerable scope. He was a well-known illustrator whose work appeared in numerous newspapers and periodicals. His fine art was displayed in gallery exhibitions alongside Vuillard, Matisse and Toulouse-Lautrec. Early works were noted for their satiric characterizations of the foibles of French society. His points were made with simple caricature. His illustrations relied on blotches of pure black with minimum outline to define his animated marionettes. His exhibition pieces were carried by large splashes of color and those same fine lines of black. Hermann-Paul worked in Ripolin enamel paint, watercolors, woodcuts, lithographs, drypoint engraving, oils, and ink.

On the eve of the First World War, he made quite an impression as part of M. Druet's "First Group." As noted by the Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, the exhibition was "chiefly remarkable for a series of paintings or drawings - it is hard to say which - by M. Hermann-Paul in a new medium which is simply ripolin."[1] The Great War soon intervened and Hermann-Paul would document its tragedy as well as its foibles. After the war, he underwent several stylistic changes. In his later years, he produced many works in dry point and ink depicting his beloved Camargue.

Early work

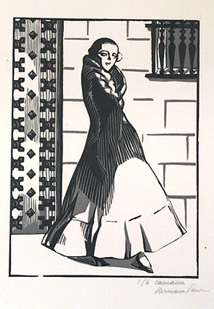

Between 1890 and 1914 he worked as a lithographer (both in color and in black and white) and as an illustrator for weekly publications such as La Faridondaine, Le Courrier Français, Le Cri de Paris, Le Figaro, Le Petit Bleu, Gil-Blas and Le Rire. Despite great elegance and beauty, his work was imbued with social criticism from the start. Although the bourgeoisie received the brunt of his mockery, Hermann-Paul prodded all aspects of Parisian society. He was critical of rich and poor alike. He attacked monarchs, paupers, politicians, clerics and elements of the established order. Peripheral players in the art world received particular attention.

As early as 1895 his famous Vie de Monsieur Quelconque and Vie de Madame Quelconque poked holes in the established understanding of the typical aspirations of the middle class in matters both public and private. By 1900 most Parisians familiar with the local news weeklies were aware of the artist's work. He was a staunch defender of Captain Alfred Dreyfus,[2] whom he considered an innocent man. The artist's suspicions were substantiated after one of Dreyfus's accusers broke down under interrogation. Hubert-Joseph Henry confessed that the damning documents were actually forged.[3] After Henry slit his throat in prison, Hermann-Paul produced a cartoon in which two people stand over the fresh grave of Major Henry. One says to the other, "This one, at least, won't give us any trouble." Avec celui-là au moins on est tranquille.

During this time, Hermann-Paul produced work in the "intimiste" style which often depicted bourgeois settings populated by women sipping tea or quietly sewing. The term was coined – derisively, it seems – by Édouard Vuillard who used it to describe his own style.[4] Other practitioners include Maurice Lobre, Hughes de Beaumont, Henri Matisse, Rene Prinet and Ernest Laurent. The Intimists first collective exhibition was shown at Henry Grave's galleries in 1905.[5] The exhibition included several works by Hermann-Paul.

The Great War

By the summer of 1914, Hermann-Paul was firmly entrenched in the political left. A decade earlier, the Dreyfus Affair cleaved the country decisively along the lines of left and right; there was little doubt as to where the artist stood. Dreyfusards tended to be radicals, liberals, republicans, anti-clericals and pacificsts. Their opponents tended to be royalists, conservatives, anti-Semites, and supporters of the church and army.[6] In the years leading up to the war, Hermann-Paul's political commentary was consistent with the views of the political left. There was nothing in his published work to indicate the sharp turn he was about to take.

When the war began that fateful summer, the general populace was caught completely off guard. It arrived in Europe like a "peal of thunder reverberating in a clear sky."[7] For Hermann-Paul, there was little doubt as to who was responsible; he blamed the Germans whose armies were marching toward Paris.

Hermann-Paul was almost fifty when the Great War began. As an energetic man, he was likely hobbled by a general sense of uselessness. He channeled that energy into his art and he proceeded to document the war. It was at this time, when the artist switched mediums. His earlier print work required metal which was suddenly in short supply. By necessity, Hermann-Paul switched to wood. He started making woodcuts.

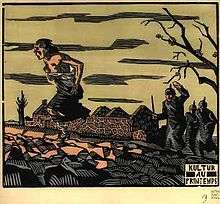

His first major series in wood was The Four Seasons of Culture, a series of five woodcuts that depicted atrocities committed the Germans in Belgium. The series is rich in texture and stunning in its detail. It depicts looting, burning and rape. It was met with immediate backlash from the political left.

With his depiction of a brutal enemy raping its way across Europe, critics on the left claimed he was helping to shut down avenues toward peace. Negotiations were impossible with Hermann-Paul's brutal Bosch. This type of work would only help prolong the war, they said.

His next major work did little to placate his new found critics. It was entitled Calendrier de la Guerre, Calendar of the War. It tends to promote patriotic attitudes toward the war and the generals who conducted it. For the left, these were the generals who senselessly sent young men to slaughter in pointless attacks against entrenched machine guns. As far as they were concerned, Hermann-Paul became a traitor to the cause of peace.

Post-war

After the war, he continued to work in the media he discovered by circumstance. Metal shortages compelled him to search for another print form and that's when he discovered the modernist woodcut. He would continue to work in wood until age started to get the best of him in the late 1930s. During this time, he produced many fine art prints and book illustrations.

Hermann-Paul did a sizeable number of illustrations for Candide in the interwar period, but these were the exception rather than the rule. Wood was without question, his primary form. His post-war illustrations tended to be apolitical, in stark contrast with his pre-war work.

Hermann-Paul's first major post-war work was a morbid series of woodcuts in book form, The Dance With Death La danse macabre; vingt gravures sur bois. The series depicts death's passage through the modern world. Men are seen as isolated and lonely creatures. The meaning of individual works is not always clear but the series is a firm indictment of modern mechanized warfare. It did little to placate old allies.

Unable to mend old fences with the political left and not disposed toward the tendencies of the right, Hermann-Paul abandoned politics in the interwar period. His inspirations become more literary than journalistic and his style evolved from a belle époque line to a modernist simplification.

Hermann-Paul practiced some painting on canvas, but it was never a form he mastered. First and foremost his contribution to the art world resides in his daring composition of the 1890s and 1920s in lithography and in woodcut respectively. His many book illustrations, both reproductive and original also deserve much praise, as does his immense production of journalistic satire in the 1890s through the end of the 1910s. The unique works of art that should be remembered are beautiful works on paper: pastels, color drawings, watercolors and preparatory pencil sketches for his publications.

Rediscovered

During the 1980s, the Zimmerli Museum at Rutgers acquired no fewer than 150 pieces by the artist.[8] They demonstrate a range of expression for which few collectors had previously given him credit. Interest has recently surged since Hermann-Paul’s work was rediscovered by a larger public through the auction of his earlier pieces in October 2000 in Chartres. Many drawings and prints currently on the market bear the stamp of this sale on the verso.

References

- ↑ The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 24, No. 129 (Dec., 1913), pp. 172-174

- ↑ http://www.hermann-paul.org/index/biography-illustrator. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Mysteries & Secrets - Alfred Drefus". skygaze.com. Retrieved 2007-11-16.

- ↑ Laurie Shannon, "The Country of our Friendship": Jewett's Intimist Art, American Literature, Vol. 71, No. 2, (June 1999), pp 227

- ↑ The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 7, No. 25. (Apr., 1905)

- ↑ Margaret MacMillan. "The War That Ended Peace pp. 153". Random House.

- ↑ Michael S. Neiberg. "Dance of the Furies pp. 10". Belknap Press.

- ↑ Russell, John (December 15, 1985). "Art View; Lautrec Never Looked Better". New York Times. Retrieved 1985-12-15. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hermann-Paul. |

External links

- Hermann-Paul - Online biography and illustrated gallery

- Les Amis de Job - Illustrations from Le Rire, l'Assiette au Beurre, Charivari...

- L'Assiette au Beurre - Illustrations from L'Assiette au Beurre

- Le Rire - Illustrations from Le Rire

- Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco Image search for Hermann-Paul