History of Christianity in Slovakia

The beginnings of the history of Christianity in Slovakia can most probably be traced back to the period following the collapse of the Avar Empire at the end of the 8th century. Slavic principalities emerged in the territories that had up to that time been under Avar control, and in time their rulers were ready to accept Christianity. The first Christian church erected in Slavic lands seems to have been the one consecrated for a local ruler named Pribina in Nitra around 830. The second half of the 9th century witnessed the first flourishing of Christian culture in the territories what now form Slovakia when the "Apostles of the Slavs", Cyril and Methodius were active in "Great" Moravia, an early medieval Slavic empire in Central Europe. They translated sacred and liturgical texts, and introduced Old Church Slavonic into the liturgy. Although their disciples were expelled from Moravia after 885, the "Slavic liturgy" had an enduring effect on the Slavic peoples.

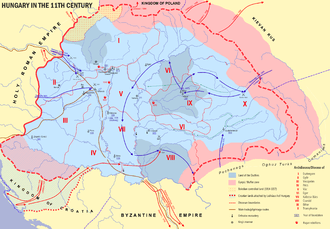

In the course of the 11th century, the plains north of the river Danube and the territories covered by the Western Carpathian Mountains were gradually incorporated into the multiethnic medieval Kingdom of Hungary. Here three Roman Catholic dioceses, many monasteries and other ecclesiastic institutions were established in the Middle Ages. In this period the Church had many responsibilities that are now assumed by state authorities (for instance, it administered schools and social institutions, and took part in royal administration), thus it was richly endowed with landed properties and other sources of income.

Among the early movements for Church Reform, the presence of Waldensians can be detected in the 14th century. Although significant parts of Slovakia were dominated by Czech Hussite soldiers in the middle of the 15th century, their behaviour (they were engaged mainly in plundering) seems to have not won them many supporters. The ideas of the 16th-century Reformation first spread among the German-speaking inhabitants of the towns, but in the middle of the century many Slovaks also embraced the Lutheran version of Protestantism. In contrast with them, a significant part of the local Hungarians became adherent to the more radical theology of Calvinism.

Antiquity

Around the time when Jesus was born, a new power-structure was emerging in the territory of present-day Slovakia, inhabited for centuries by Celtic tribes.[1] First the Germanic Marcomanni and Quadi arrived from the north and chased away the Celts.[1][2] Next the borders of the expanding Roman Empire reached the river Danube from the south.[1][2] Subsequently, the southwest regions of Slovakia turned into a battleground between the Germans and the Romans.[3]

The "Miracle of the Rain", often cited in early Christian literature, happened during a campaign the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius launched against the Quadi in 172.[4][5][6] Rather than giving battle, the Germanic warriors were luring the Romans up to the point that they were caught without supply, and without water.[6] Their situation looked set for disaster, but "suddenly many clouds gathered and a mighty rain" burst upon them.[6] Energized by the pouring rain, the Romans were able to defeat the enemy.[7] Although the Roman historian Dio Cassius attributed the "miracle" to the efforts of an Egyptian mage, Christian writers claimed that the prayers of a Christian legion from Syria had worked it.[7]

There are very few indications that Roman religious cults had any impact on the Germanic peoples outside the Roman Empire.[8] Scarcely was greater the impact of Christianity.[8] One of the few examples is Fritigir, queen of the Marcomanni, who met a Christian traveller from the Roman Empire shortly before 397.[8] He talked to her of Ambrose, the formidable bishop of Milan (Italy).[8] Impressed by what she heard, the queen converted to Christianity.[9][10]

Early Slavs

The first written source suggesting that Slavic tribes established themselves in what is now Slovakia is connected to the migration of the Germanic Heruli from the Middle Danube region towards Scandinavia in 512.[11][12] This year, according to Procopius, they first passed "through the land of the Slavs", most probably along the river Morava.[13] A cluster of archaeological sites in the valleys of the rivers Morava, Váh and Hron also suggests that at the latest the earliest Slavic settlements appeared in the territory around 500.[14][15] They are characterized by vessels similar to those of the "Mogiła" group of southern Poland and having analogies in the "Korchak" pottery of Ukraine.[16]

Written evidence of the spiritual life of and the cults practiced by the early Slavs comes from a relatively late period (from the 11th–12th centuries).[17] Ancient Slavic religion seems to have been concerned with nature, and especially fertility.[18] On the basis of rural folk beliefs recorded in Slovakia, an earlier belief in water spirits (vodniki) can be concluded.[19] Most early Slav burials were made either in flat cremation cemeteries or by a rite which leaves absolutely no recoverable remains.[20] In contrast with them, the Avars (an alliance of nomadic groups formed on the Eurasian Steppe who subjugated the Slavic tribes after 568) practiced inhumation, sometime with horses, in flat cemeteries.[20][21][22]

The Slavs' resistance against the Avars began in 623–624, with a Frankish merchant named Samo taking the lead.[21] He accepted Slavic customs (including polygamy), and brought many Slavic tribes under his rule.[23][24] Whether his "kingdom" also included territories of modern Slovakia remained subject to scholarly debate.[25] Similarly, the idea that he was a zealous Christian and put in hand his subjects' evangelization has not been proven.[26] All the same, following Samo's death around 659, Avar power was reestablished for another 150 years.[24][27]

The period around 650 experienced an apparent change in burial rite: barrows with horizontal wooden revetting at the base of the mound appeared in the region, and the cremated remains were deposited on the top of the mound.[20] The Slavs seems to have come under Avar cultural influence, and acquired some of their religious practices.[28] Many burials and grave goods from the 7th–8th centuries unearthed at Devínska Nová Ves exhibit distinctly Avar elements.[28]

Avar power was broken at the end of the 8th century by Charlemagne, king of the Franks.[29] First they were defeated between 791 and 795 in a series of military campaigns, then converted to Christianity, and finally resettled on the borderlands between present-day Austria and Hungary.[30][31] The fall of the Avars created a political vacuum in the territories between the Carolingian and the Byzantine Empires, which was filled by Slavic polities.[32] Under "Late Avar" and Carolingian influences a new style of metalwork, the "Blatnica-Mikulčice horizon" appeared in the region.[33] The Royal Frankish Annals first report under the year 811 that "leaders of the Slavs who live along the Danube" appeared at Aachen (Germany), the capital of the Frankish Empire.[34][35][36]

"Nitrava" and "Great" Moravia

Towards conversion

A tract written around 870 by a clergyman from Salzburg (Austria) known as the Conversion of the Bavarians and the Carantanians narrates that Adalram, archbishop of Salzburg consecrated a church in "Nitrava ultra Danubium" around 830.[37][38][39] If "Nitrava" is identical with the modern town of Nitra, the first Christian church erected on Slavic territory was built in Slovakia.[40][41] It was consecrated for Pribina who either ruled the town as its prince or held it as the lieutenant of Mojmír I, the first known ruler of Moravia (c. 830–846).[42][43][44][45] Be that as it may, the Moravian ruler drove Pribina out of "Nitrava" around 833.[43][44] He fled to the Eastern Frankish kingdom, where he was soon baptized.[41][46] Thus Pribina might have been the first Slavic ruler to convert Christianity.[41]

The existence of "princes" in Moravia had already been mentioned under the year 822 by the Royal Frankish Annals.[47] A mass baptism of Moravian Slavs is recorded for 831 by Reginhar, bishop of Passau (Germany).[44] Their ruler, Mojmír I also received baptism at the latest around that time.[44][48] The ceremony, however, did not put an end to paganism in Moravia: although cremations seem to have relatively quickly been replaced by inhumation burials, the custom of placing grave goods still lasted.[49][50]

The institutional framework of Christianity also remained unstable.[49] Priests arrived in Moravia from many places (from the Frankish Empire, from Italy and from Dalmatia), and taught according to their own customs.[49] They set differing penances, observed the feast days and fasts differently, and adjusted marriage affairs variously.[49] Furthermore, the work of missionaries seems to have slackened off somewhat, especially after Hartwig, bishop of Passau suffered a stroke and became disabled for years.[51][52]

Saints Cyril and Methodius

In 862 Mojmír I's successor, Rastislav (846–870) approached Pope Nicholas I to send missionaries who were familiar with the Slavic language.[49][53] Having met no success, next year he turned to the Byzantine Emperor Michael III, demanding "a bishop and a teacher" to be sent to Moravia.[47][54] The emperor assigned two brothers named Constantine and Methodius to the task.[55] Before long Constantine came to the conclusion that a special script fitted to Slavic would be needed for education.[56] When designing the new alphabet, he take into consideration the Slavic dialect he was familiar with, that is the one spoken in the hinterland of Thessaloniki (Greece).[56] Next he embarked on the first translation of a Christian text, the beginning of the Gospel of John, into Old Church Slavonic.[56]

The two brothers arrived in Moravia in 863.[57] Here Constantine established a school for the training of priests with Slavic as the language of both instruction and liturgy.[58] At that time, a narrow "trilingual" view was dominant in the Western Church, which held that Hebrew, Greek and Latin were the only proper languages of liturgy.[59][60] The arrival of the two brothers also impaired the missionary activity of the German priests, which gave rise to friction with them.[53][61] In addition, Constantine reproached them for "not preventing the holding of sacrifices according to the earlier" (pagan) custom.[48][62] Nevertheless, Constantine and Methodius took into account the Christian vocabulary established in Moravia before their arrival, and adopted many words of German or Latin origin into Old Church Slavonic.[63] For instance, words like postŭ ("fast") and vŭsodŭ ("communion") were borrowed from German.[63]

Because God's Word was spreading, the evil envier from the days of creation, the thrice-accursed Devil, was unable to bear this good and entered his vessels. (…) These were the cohorts of the Latin speaking, archpriests, priests, and their disciples. And having fought with them like David with the Philistines, Constantine defeated them with words from the Scriptures, and called them trilinguists, since Pilate had thus written the Lord's title. The Life of Constantine[62]

Constantine and Methodius left Moravia in 867, and decided to proceed to Rome.[64][65] Here Pope Adrian II consented to accept their "Slav books" and to ordain four of their disciples.[66] In short time the ailing Constantine took monastic vows, assumed the monastic name of Cyril, and died on February 14, 868.[53][67] His brother was consecrated in 870 by the pope archbishop of Sirmium (Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia) with the supplementary dignity of papal legate of all the territories ruled by Rastislav of Moravia, his nephew, Svatopluk, and Kocel of Pannonia (the son of Pribina).[68][69][70] Upon returning to Moravia, however, Methodius was arrested by Bavarian bishops.[71] He was only released at the command of Pope John VIII in 873.[71] Although the pope forbade him to use the Slavic liturgy, Methodius disobeyed after his return to Moravia.[72]

The new ruler of Moravia, Svatopluk I (871–894) never gave Methodius his unqualified support.[73][74] Accused of heresy by the German clergy, Methodius travelled again to Rome in 879.[72] Here he persuaded Pope John VIII to issue a bull known as Industriae tuae in June 880, which approved the liturgy to be officiated in Old Church Slavonic in Moravia, although with the provision that the Gospels first be read in Latin.[71] Upon Svatopluk I's request, the bull ordered that in his court mass could be said in Latin, as well.[71] At the same time, the pope consecrated a Swabian monk named Wiching bishop of the newly established see of Nitra ("sancta ecclesia Nitriensis").[70][72] Some 20 years later Theotmar, archbishop of Salzburg wrote that the Bavarian bishops had not objected Wiching's appointment, because he was sent "to a newly baptized people whom" Svatopluk I "had defeated in war and converted from paganism to Christianity".[75]

And Prince Svatopluk and all the Moravians received him (Methodius). They entrusted to him all the churches and clergy in all the towns. And from that day forth, God's teaching grew greatly and the clergy multiplied in all the towns. And for that reason the Moravians began to grow and multiply, and the pagans to believe in the true God, casting aside their lies. And the Province of Moravia began to expand much more into all lands and to defeat its enemies successfully, as they themselves are always relating. (...) When Svatopluk was warring without success against the pagans and faltering, and Saint Peter's Day Mass, that is, the liturgy drew nigh, Methodius sent to him, saying: "If you promise me that you and your soldiers will celebrate Saint Peter's Day with me, I trust God will soon deliver them to you." And so it came to pass.— The Life of Methodius[76]

Methodius died on April 6, 885, but only after designating one of his disciples, Gorazd as his successor.[77] However, based on the false testimony of Bishop Wiching who was right in Rome on a diplomatic mission Pope Stephen V forbade liturgy to be officiated in Old Church Slavonic, and restricted its use to sermons and to the exposition of biblical texts.[77][78] The pope expressed his directions in a letter known as Quia te zelo.[77] As Methodius's disciples refused to submit to the pope's commands, Wiching set about persecuting them as soon as he returned to Moravia.[77] Their leaders were first thrown into prison, but at least one of them, Naum was sold as slave.[79] Finally, Svatopluk I expelled all monks trained in the Slav rite from his realm at the instigation of the German clergy.[60]

Fall

Moravia was left without a recognized prelate when Bishop Wiching deserted Svatopluk I for Arnulf I, king of East Francia in 891.[77][80] Svatopluk I was succeeded by his son Mojmir II (894–906), with whom the disintegration of Moravia commenced.[74][81] Early in his reign Hungarian tribes established themselves in the eastern part of the Great Hungarian Plain, and time to time intervened in the conflicts between Moravia and East Francia.[82]

Mojmir II petitioned Pope John IX to reinstate the archbishopric in Moravia in 898.[80] The pope agreed to consecrate an archbishop and three bishops, but it is not wholly clear whether this intention was ever carried out.[80][83] What is for certain that around 900 the Bavarian bishops led by Archbishop Theotmar of Salzburg protested against the presence of three papal legates in Moravia.[84]

A document known as the "Raffelstädt tool rate" refers to the markets of the Moravians, which proves that shipping on the Danube was still free around 904, although the Hungarians had by that time conquered the territories of present-day Hungary west of the river.[83][85] Moravia ceased to exist as a state in the summer of 907 at the latest, when the Hungarians defeated a Bavarian army near "Brezalauspurc" (identified, although not unanimously, with Bratislava).[83][86] Even thereafter, Hungarian military settlements seems to have been limited to the southern part of Slovakia, since no grave of Hungarian warriors from the first half of the 10th century have been found beyond the line formed by Bratislava, Trnava, Hlohovec, Nitra, Levice, Lučenec, Moldava nad Bodvou, and Trebišov.[87]

Legacy

Not many relics of "Great" Moravia have so far been identified in Slovakia.[88] Indubitably of "Great" Moravian provenance are some sacral objects found on Bratislava's fort mound, as well as the church on Martin's Hill in Nitra, the round chapel near Ducové, and the church on the fortified promontory of Devín.[88][89] Their ruins, however, did not influence later Christian architecture, their pieces were only reused as building material.[89]

The unbroken existence of any Christian community with properly ordained priests in the 10th century is hardly susceptible of proof.[90] Christian teaching may have been retained in small enclaves, but the idea that church dedications "of eremite origin" prove the existence of a dense network of hermitages in this period has not received unanimous support.[91] Neither has been proven the survival of the Benedictine monastery, allegedly founded in the 9th century, on Mount Zobor near Nitra.[90]

In the same year, Svatopluk, the king of Moravia – as it is commonly said – fled in the midst of his army and was never seen again. But the truth of the matter is that he came to himself when he recognized that he had unjustly taken up arms against his lord emperor and fellow-father Arnulf, as if forgetting his benefice. For Svatopluk had subjugated not only Bohemia but other regions as well, from there all the way to the River Oder and toward Hungary to the River Gron. Having repented, with no one knowing of it in the darkness, he got on his horse in the middle of the night and, passing through his camp, fled to a place on the side of Mt. Zobor, where three hermits had once built a church with his money and assistance in a great forest inaccessible to men. When he arrived there, he killed the horse in a secret place in the forest, buried his sword in the ground, and, with the light of day dawning, approached the hermits. Without their knowing who he was, Svatopluk was tonsured and dressed in hermit's grab. As long as he lived, he remained unknown to everyone. He told the monks with him who he was only when he realized death was at hand – and died immediately thereafter.

The translations made by Saints Cyril and Methodius, and the introduction of the liturgy officiated in Old Church Slavonic constitute the most enduring legacy of "Great" Moravia.[93] The establishment of a literary language with its own scripts potentially allowed Christianity to reach all members of the congregation, and not just those familiar with the classical languages.[94] The Lifes of the two saints specifically record that they translated, besides the Divine Office, the whole Bible with the exception of the Books of the Maccabees.[95] Expelled from Moravia, many disciples of Cyril and Methodius left for Bulgaria where Old Church Slavonic was again introduced for liturgical use.[96]

Middle Ages

The local Slavic population survived the Hungarian conquest.[97] Some forms of pottery are continuous before and after the conquest, and place names entered Hungarian from Slavic.[97] Likewise, nearly all the basic terms of Christianity of the Hungarian language, along with the names of four days, are of Slavic origin.[98] For instance, words like keresztel ("to baptize"), püspök ("bishop"), and csütörtök ("Thursday") were borrowed from the Slavic inhabitants of the Carpathian Basin.[98][99]

The consolidation of the Hungarian state began with Géza (c. 972–997).[100] He also allowed Christianity to freely spread, mainly through the efforts of German clergy, in the territories under his rule.[100] For instance, Piligrim, bishop of Passau who sent missionaries in 973–974 to Géza's realm claimed that they converted many leading men, and even Christian slaves were now allowed to practice their religion.[101]

The formal establishment of the Christian kingdom was the achievement of Géza's son, Stephen (997–1038).[102] He was first opposed by one of his kinsmen, Koppány who claimed the succession on the basis of seniority.[100][102] Stephen defeated him in a battle near Veszprém (Hungary) in 998.[102][103] Two knights, Hunt and Poznan who are described as "newcomers" (Latin: advena) "of Swabian origin" in medieval chronicles played a preeminent role in the victory.[100][103][104][105] Based on archaeological research started in manor houses in Slovakia in the 1970s, Slovak historiography tends to refer to them as "Slavic" or "Slovak magnates" from the "Principality of Nitra".[100][106][107]

After his victory over Koppány, Stephen was crowned the first king of Hungary in 1000 or 1001.[100][108] He soon set about organizing the Church by establishing dioceses and by assigning to every ten villages the responsibility of building a church together to serve their community.[109] Most territories of present-day Slovakia were put under the jurisdiction of the archbishop of Esztergom (Hungary), who was to be the head of the Catholic hierarchy in the entire kingdom; Slovakia's eastern territories belonged to the diocese of Eger (Hungary).[109][110]

One of the first archbishops of Esztergom was Astrik, a former abbot of the Benedictine monastery of Břevnov (Czech Republic).[107] He had arrived in the retinue of Adalbert, bishop of Prague (Czech Republic).[107] In Stephen I's reign, other clergymen also came to the kingdom.[111] Among them, two hermits named Svorad and Benedict who arrived from Poland or Istria (Croatia) around 1022 settled in the Benedictine monastery on Mount Zobor.[90][111][112] The Slovak historian Richard Marsina refers to them as "the oldest and first, in the true and full sense of the word, Slovak saints".[113]

Stephen I granted extensive property to the Church, and introduced the tithes, an ecclesiastic tax to be paid by the peasantry on grain, wine and other agricultural products.[98][109][114] Beside secular clergy, Benedictine monks played an active role in the process of Christianization.[112][115] Stephen I endowed (or according to tradition founded) their monastery on Mount Zobor, and one of his successors, Géza I (1074–1077) established a Benedictine abbey at Hronský Beňadik in 1075.[115][116][117] Donations made by noblemen also increased Church property.[118] For instance, not long before 1132 Lambert and his son, Nicholas (descendants of Hunt or Poznan) founded a Benedictine monastery at Bzovík, and donated estates and serfs in 23 settlements of their domains to the monks.[119][120]

Lambert himself was the brother-in-law of King Ladislaus I (1074–1095).[119] In his reign, the synod of Szabolcs (Hungary) of 1092 regulated in details several aspects of patronage rights and of clerical status, as well as the collection of the tithes and the celebration of feasts.[98][117] Stephen I, his son Emeric, and the hermits Svorad and Benedict were also canonized in his reign.[121] Many churches dedicated to the holy king prove that his cult spread in the territories what now form Slovakia.[122]

Ladislaus I himself was canonized in 1192.[123] Whether the diocese of Nitra (the only bishopric with a see in Slovakia for centuries) had been set up by him or by his nephew Coloman (1095–1116) has not been decided by historians.[122][124] Under Coloman, legislation on internal ecclesiastical matters radically increased, including the regulation of the life of canons and monks, and the compulsory attendance of clerics at synods convoked by their bishops.[125]

In addition to monasteries, chapters (ecclesiastic bodies centered around cathedrals and consisting of canons who assisted the bishops in administering their dioceses) were organized in the major towns.[112][126] The earliest example is the collegiate chapter established in Bratislava around 1100.[127] Many monasteries and chapters administered schools (for instance, the Benedictine monastery at Krásna became an important cultural center).[128][129] Ecclesiastic institutions designated as "places of authentication" (Latin: locus credibilis) performed the functions of modern public notaries by issuing, copying and confirming documents, and inspecting property transfers.[130][131]

From the 12th century, new monastic orders arrived in the kingdom.[112] Cistercian abbeys were established at Lipovnik in 1141, at Štiavnik in 1223, and a cloister for Cistercian nuns at Bratislava in 1235.[112] The earliest Premonstratensian abbey was founded at Leles in 1190 by Boleslav, bishop of Vác (Hungary), but the monasteries at Jasov, at Šahy, and at Kláštor pod Znievom were also established for them in the early 13th century.[112][132] Among the mendicant orders, the Dominicans settled in Košice in the first half of the 13th century, while the Franciscans in Košice, in Nitra and in Trnava before 1241.[112][133] The order of Franciscan nuns known as Poor Clares even replaced the older Cistercian foundations in Trnava and Bratislava.[134] The mendicant friars devoted themselves to preaching and teaching, settled primarily in towns, and were active especially among the poor.[133]

Towns were created by royal charters bestowing a wide range of privileges to their inhabitants (including the right to freely erect their mayors).[135][136] Trnava, Starý Tekov, Zvolen and Krupina were the first settlements receiving such privileges around 1238, but they were joined by Nitra, Košice, Banská Štiavnica, Bratislava, and other localities in the course of the 13th–14th centuries.[135][136] German colonists settled in Spiš county received collective from King Stephen V of Hungary (1270–1272), which resulted in the establishment of their autonomous community known as the "University of the Saxons of Spiš".[137][138] Colonists from the West, especially from the Holy Roman Empire, played an important role in the development of all the towns in the Kingdom of Hungary.[135] Thus German speakers became the most numerous segment of the town populations, but Jews, Slavic-speaking colonists and local Slavs, and Hungarians also settled in them.[139] For instance, Gašpar Bak, prior of the Spiš Chapter wrote prayers in Slavic vernacular on the anniversary of his consecration in 1479; and antagonism between Slovak and German speakers in Trnava over the choice of a parish priests required royal intervention in 1486.[140][141]

In addition to preaching and running schools and hospitals, searching for and trial of heretics was the Dominican friars' main responsibility.[142] The first known inquisition against heretics was carried out in the archdiocese of Esztergom in 1328.[143] At the beginning of the 15th century, a community of Waldensians was uncovered in Trnava.[143] The Hussite movement reached the northern parts of the kingdom when Czech Hussites under the leadership of Prokop Holý invaded the territory in 1428.[144][145] They occupied Trnava, Skalica, and other towns for a short period, but soon returned to Moravia.[144][146] In the next decade they made several incursions, reaching as far as Spiš county.[146][147]

The heyday of the Hussite movement began in 1440 when the Dowager Queen Elisabeth hired a Czech nobleman Jan Jiskra of Brandýs to defend the interest of her infant son, Ladislaus V the Posthumous (1440–1457) against his opponent, Vladislav I (1440–1444).[148] Jan Jiskra recruited about 5,000 Czech mercenaries, most of them Hussite soldiers, and occupied Zvolen and nearby towns.[149] He was even elected one of the seven "captains general" governing the kingdom in 1445 by the legislative assembly of the Estates known as the Diet.[146][150]

Thereafter Hussites from Moravia, Bohemia and Poland joined him.[149] Many of them left military service and made a living by robbery and plunder.[149] They addressed each other as "Bratrik", thus they became known as "Brethren" in the kingdom.[149][151] In short time, their number increased to 16,000, and they settled in fortified camps and fortresses mainly in Spiš, Šariš, Abov and Zemplín counties.[149] They time to time stormed and pillaged monasteries, and regularly attacked merchants travelling from or to Poland.[149] The authorities became more and more concerned about the aggressive behavior of the "Brethren".[149] First they hired Jan Jiskra who had in the meantime left the kingdom to remove them with force, and he routed them at Trebišov in 1454.[146][149] However, their last camp (near Veľké Kostoľany) was only liquidated in 1467 by King Matthias I.[149][152]

Early Modern and Modern Times

Reformation

The ideas of Reformation spread from Germany to the Kingdom of Hungary.[153] Accordingly, the towns in the Northern Carpathians, with their predominantly German population, were the first locations affected by the ideas of Martin Luther.[153][154] His Ninety-Five Theses were first read publicly in Ľubica in 1521 by Thomas Preisner.[155] The spread of "German heresy" soon alarmed both the Catholic prelates and the nobility.[156] Therefore, in 1523 the Diet adopted a law ordering that anyone confessing Lutheran ideas should be confiscated of their property and punished with death.[156]

The army of the kingdom was routed by the Ottomans in the Battle of Mohács (Hungary) on August 29, 1526.[157][158] In the battlefield both archbishops and five bishops perished, which left the Catholic Church practically bereft of its local leaders.[159][160] As King Louis II (1516–1526) drowned in a flooding creek after the battle, his brother-in-law, Ferdinand (a scion of the Habsburg family) announced his claim to the throne.[158] He was, however, soon contested by John Szapolyai, the wealthiest landowner in the kingdom.[161] Both claimants were proclaimed and crowned king, which resulted in a civil war that was to last for decades.[161][162]

Most territories of present-day Slovakia were ruled by Ferdinand I (1526–1564), which accidentally contributed to the further spread of Protestant ideas.[153][163] In need of allies in his struggle for the throne, the king pursued a tolerant policy towards the towns and the noblemen.[153] During the 1530s and 1540s, most of the major cities installed Lutheran reformers as preachers or city pastors.[160] For instance, Wolfgang Schustel who adopted an uncompromising position on public piety worked in Prešov and other towns; the Croatian Michal Radašin was called as town pastor to Bardejov; in Košice the Reformation was introduced by a number of preachers, including the Hungarian Mátyás Dévai Bíró.[164]

Among the landed nobility Protestantism began to spread from the 1530s.[165] Members of the Révay, Thurzó, Kostka, and other leading noble families adopted the Lutheran ideas in this period.[166][167] Even the viceroy, Alexis Thurzó, and the bishop of Nitra, Francis Thurzó embraced Lutheranism.[166][168] Slovak or "windisch" (Slavic) pastors appointed by Protestant city councils or local noblemen draw more and more Slovak believers to the Reformation.[167] For instance, Stanislaus Koskossinus worked in Zvolen, while Georgius Bohemicus in Trenčín, and Gašpar Kolarik in Orava counties.[167]

The medieval Kingdom of Hungary was divided into three parts following the occupation of its capital, Buda (Budapest, Hungary) by the Ottomans in 1541.[169] Most territories of present-day Slovakia remained ruled by the Habsburg kings.[170] Together with modern Burgenland in Austria and the westernmost parts of present-day Hungary, they formed "Royal Hungary".[171] The central territories of the kingdom were annexed by the Ottoman Empire, while the lands east of the river Tisza remained under the rule of John II Sigismund (1541–1571), the son of John Szapolyai.[169]

Meanwhile, conflicts emerged between partisans of moderate reforms and those favoring more radical views.[172] In Spiš Andreas Fischer, a convert to Anabaptism called for a thorough reform of church and society and a strict adherence to the Ten Commandments already in 1529.[173] He was soon forced to leave the city.[168] Hungarian pastors, exposed to heterodox ideas originating in southern Germany and Switzerland, were drawn towards "Sacramentarian" views of Eucharist, regarding it as a mere memorial of Christ's death.[174]

Reformation was first formally introduced in the twenty-four Saxon cities of Spiš in 1544.[173] After the Diet of 1548 adopted strict measures against Anabaptist and "Sacramentarian" ideas, the predominantly Lutheran cities adopted a series of Confessions of Faith based on the Augsburg Confession in order to avoid the risk of being associated with views outlawed by the Diet.[174][175] First five eastern towns (Levoča, Prešov, Bardejov, Košice, and Sabinov) agreed to the so-called "Confessio Pentepolitana" in 1549.[166][175] It was followed in 1559 by the "Confessio Heptapolitana" issued by seven mining towns, and in 1569 by the "Confessio Scepusiana" adopted by twenty-four Saxon towns in Spiš.[166][175] Hereafter the moderate Lutheran form of Reformation predominated across the northern parts of "Royal Hungary".[175] Externally it was characterized by communion under both kinds (Bread and Wine), by the simplification of both worship services and the embellishment of churches, by permitting the marriage of the clergy, and by the introduction of vernacular as the language of liturgy.[176]

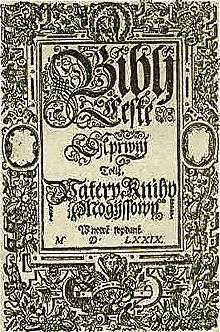

By the 1570s, there were about 900 Protestant parishes in Slovakia.[177] In the towns, the Lutheran Church regularly was divided into separate German and Slovak parishes, each with its own church and baptismal records, and often with its own cemetery.[178] In officiating the liturgy, Slovak pastors used the "bibličtina" ("biblical language"), a version of the Czech language, interspersed with Slovakisms.[178][179] It was based on the Bible of Kralice, the Czech translation of the Bible published in six volumes between 1579 and 1593.[179][180]

While the Slovak and German population embraced the ideas of the Lutheran Reformation, the Hungarians came under the influence of Calvinism.[181] From the late 1550s, Hungarian ministers' started to openly deny the real presence of the Body and Blood of Christ in the Eucharist.[182] In 1567 a synod of Hungarian pastors held at Debrecen (Hungary) agreed to the "Debrecen Confession", based on the "Heidelberg Catechism" of 1563 and the "Second Helvetic Confession of Faith" of 1566.[181][183] However, due to anti-Calvinist legislation that continued to be promulgated in "Royal Hungary" in the 1560s and 1570s, a separate Reformed church administration only appeared after the 1592 synod of Galanta.[184]

Counter-Reformation

In spite of the support the Catholic Church received from the Habsburg monarchs, it could primarily maintain its position in the southwestern regions where the central royal offices moved to escape the Ottomans.[177] When the Ottomans occupied Esztergom in 1543, the see of the archdiocese was also transferred to Trnava.[185] The first steps towards Counter-Reformation were taken by Miklós Oláh, archbishop of Esztergom.[186] By merging the two schools so far administered by the city and the chapter in Trnava in 1555, he established an institution for training a new generation of Catholic clergymen.[176] The pupils were also mastered the languages spoken in "Royal Hungary", thus there was always a teacher who spoke the Slovak language.[176] In 1561 the archbishop invited the Jesuits to the town in order to establish a seminary there.[176][187] It carried out its academic mission until 1567, when its buildings were destroyed by fire.[187]

A new phase of the Counter-Reformation began in January, 1604 when Giacomo Barbiano di Belgiojoso, imperial commander of Upper Hungary, forcibly seized the main church of Košice from the Lutherans, and handed it over to the Catholics at the initiative of the Catholic prelates.[177][188] When the Lutheran Estates objected, King Rudolf I (1576–1608) ordered the maintenance of the still existing anti-Reformation laws, and forbade the Diet to discuss religious issues.[177][188][189] Consequently, the Protestant noblemen and towns of Royal Hungary joined the uprising initiated against the Habsburgs in 1604 by István Bocskai, a Calvinist magnate in the Principality of Transylvania.[177][188][190] He forced the monarch to sign the Treaty of Vienna on June 23, 1606, which granted the freedom of religion to the two Protestant denominations.[177][191]

The Protestants used their freedom, also confirmed by the Diet of 1608, to build up their Church organization.[192] The Lutheran synod of Žilina of 1610 established three Church districts for the western and central territories, each being administered by a Hungarian and a German inspector.[192] In the eastern regions, two districts were established (one for the royal towns, and the other one for the counties) in 1614 at the synod of Spišské Podhradie.[192]

During the first phase of the Thirty Years' War, in 1619 Gabriel Bethlen, the Calvinist prince of Transylvania invaded "Royal Hungary".[193] His troops occupied Košice where they tortured to death the Jesuit Štefan Pongrác and Melchior Grodeczki, and the canon Marko Krizin (thereafter known together as the "Martyrs of Košice") on September 7, 1619.[194] Although Gabriel Bethlen was proclaimed king by the Protestant Estates of Royal Hungary, he concluded a treaty with the Habsburg monarch on December 31, 1621.[194][195] By signing the Treaty of Nikolsberg, King Ferdinand II (1619–1637) reconfirmed his earlier promise of religious toleration in "Royal Hungary", and ceded its eastern territories to the prince of Transylvania.[196]

Péter Pázmány, archbishop of Esztergom (1616–1637) was one of the most influential leaders of the Counter-Reformation in "Royal Hungary".[197] In 1624 he founded a boarding school for young noblemen in Trnava, in 1626 a Jesuit college in Bratislava, and in 1635 a university in Trnava.[198] The University of Trnava, with its theological and philosophical faculties, became the center of Counter-Reformation.[199][200] In addition, he personally converted virtually all of the magnate families of "Royal Hungary" to the Catholic faith.[201] Once converted, they exercised their power to enforce the Catholicization of the peasants living in their domains, either by promoting the work of missionaries or by removing all Protestant churches and preachers, which led to quarrels between the Catholic and Protestant Estates.[201][202] Once again a prince of Transylvania, George I Rákóczi declared himself protector of the Protestants in Royal Hungary, and began invading the kingdom.[202] In the Treaty of Linz, concluded on December 16, 1644, King Ferdinand III (1637–1657) was forced to extend the freedom of Protestant denominations to the peasantry.[202][203]

Religious struggles also contributed to the development of education and culture.[204] The Protestant schools in Trenčín, Košice, Levoča, Kežmarok, Bardejov, and Banská Bystrica flourished in this period.[204] On the Catholic side, the Jesuits founded high schools in Komárno, Trenčín, and Skalica.[204] New Catholic religious orders also established houses in many settlements.[205] For instance, the Brothers of Mercy settled in Spišské Podhradie in 1650, the Capuchins took up residence in Pezinok in 1674, the Piarists organized schools in Podolínec in 1642 and in Prievidza in 1666, while from 1676 the Ursulines ran schools for girls in Bratislava.[204][205] The main Protestant hymnbook of the period, the Cithara Sanctorum ("Harp of the Saints"), compiled by Jiří Třanovský, was published in 1636.[206][207] It is a collection of 414 songs, of which 40 are written in Slovak.[208] The Catholic hymnal, published under the title Cantus Catholici ("Catholic Songs") in 1655, was compiled by Benedikt Szőllősi.[186][207][209]

See also

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 13.

- 1 2 Kirschbaum 2005, p. 16.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2005, pp. 16-17.

- ↑ Mócsy 1974, p. 188.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2005, p. 17.

- 1 2 3 Heather 2010, p. 94.

- 1 2 Heather 2010, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 4 Todd 2004, p. 118.

- ↑ Mócsy 1974, p. 345.

- ↑ Todd 2004, p. 119.

- ↑ Heather 2010, pp. 407-408.

- ↑ Barford 2001, p. 53.

- ↑ Heather 2010, p. 408.

- ↑ Heather 2010, pp. 409-410.

- ↑ Barford 2001, p. 54.

- ↑ Barford 2001, pp. 53-54.

- ↑ Barford 2001, p. 188.

- ↑ Barford 2001, p. 194.

- ↑ Barford 2001, p. 190.

- 1 2 3 Barford 2001, p. 81.

- 1 2 Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 17.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, pp. xxii., 51.

- ↑ Barford 2001, p. 79.

- 1 2 Vlasto 1970, p. 20.

- ↑ Barford 2001, pp. 79-80.

- ↑ Vlasto 1970, pp. 20-21.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2005, p. 19.

- 1 2 Vlasto 1970, p. 21.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2005, p. 20.

- ↑ Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 19.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, pp. 53-57.

- ↑ Urbańczyk 2005, pp. 144-145.

- ↑ Barford 2001, pp. 109., 163.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, p. 60.

- ↑ Barford 2001, p. 109.

- ↑ Royal Frankish Annals (1972), p. 94.

- ↑ Vlasto 1970, pp. 24., 69.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2005, pp. 25., 318.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, p. 105.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, pp. 105-106.

- 1 2 3 Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 20.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, p. 14.

- 1 2 Barford 2001, p. 298.

- 1 2 3 4 Vlasto 1970, p. 24.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, p. 232.

- ↑ Barford 2001, p. 218.

- 1 2 Urbańczyk 2005, p. 145.

- 1 2 Sommer et al. 2007, p. 221.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sommer et al. 2007, p. 222.

- ↑ Barford 2001, pp. 224-225.

- ↑ Vlasto 1970, p. 26.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, p. 158.

- 1 2 3 Bartl 2002, p. 20.

- ↑ The Life of Constantine (1983), p. 65.

- ↑ Vlasto 1970, p. 28.

- 1 2 3 Vlasto 1970, p. 37.

- ↑ Sommer et al. 2007, p. 22.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, p. 87.

- ↑ Vlasto 1970, pp. 45-46.

- 1 2 Barford 2001, p. 219.

- ↑ Vlasto 1970, p. 47.

- 1 2 The Life of Constantine (1983), p. 69.

- 1 2 Vlasto 1970, p. 58.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2005, p. 31.

- ↑ Vlasto 1970, p. 51.

- ↑ Vlasto 1970, pp. 54., 56.

- ↑ Vlasto 1970, p. 56.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, pp. 153-164.

- ↑ Vlasto 1970, p. 67.

- 1 2 Bowlus 1994, p. 163.

- 1 2 3 4 Bartl 2002, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 Kirschbaum 2005, p. 32.

- ↑ Vlasto 1970, p. 71.

- 1 2 Kirschbaum 2007, p. 278.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, pp. 194., 337.

- ↑ The Life of Methodius (1983), pp. 119-121.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bartl 2002, p. 22.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2005, p. 33.

- ↑ Vlasto 1970, p. 82.

- 1 2 3 Vlasto 1970, p. 83.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2005, p. 130.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, p. 34.

- 1 2 3 Bartl 2002, p. 23.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, pp. 254., 336.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, p. 264.

- ↑ Bowlus 1994, pp. 259-260.

- ↑ Lukačka 2011, p. 31.

- 1 2 Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 25.

- 1 2 Berend et al. 2007, p. 326.

- 1 2 3 Vlasto 1970, p. 84.

- ↑ Čaplovič 2000, p. 149.

- ↑ Cosmas of Prague (2009), pp. 63-64.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2005, pp. 34-35.

- ↑ Barford 2001, p. 215.

- ↑ Vlasto 1970, pp. 63.,

- ↑ Barford 2001, pp. 93., 215.

- 1 2 Berend et al. 2007, p. 327.

- 1 2 3 4 Engel 2001, p. 44.

- ↑ Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 314.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kirschbaum 2005, p. 41.

- ↑ Berend et al. 2007, pp. 329-330.

- 1 2 3 Engel 2001, p. 27.

- 1 2 Lukačka 2011, p. 33.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 86.

- ↑ Simon of Kéza (1999), p. 163.

- ↑ Lukačka 2011, pp. 31., 33.

- 1 2 3 Bartl 2002, p. 24.

- ↑ Berend et al. 2007, p. 343.

- 1 2 3 Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 29.

- ↑ Bartl 2002, p. 195.

- 1 2 Berend et al. 2007, p. 338.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kirschbaum 2005, p. 50.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2005, pp. 50., 323., 367.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2005, p. 43.

- 1 2 Berend et al. 2007, p. 352.

- ↑ Lukačka 2011, p. 34.

- 1 2 Bartl 2002, p. 27.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 82.

- 1 2 Lukačka 2011, p. 35.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 82-83.

- ↑ Berend et al. 2007, p. 337.

- 1 2 Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 30.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 32.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 43.

- ↑ Berend et al. 2007, p. 358.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, p. 72.

- ↑ Bartl 2002, p. 28.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, 58.

- ↑ Bartl 2002, p. 301.

- ↑ Bartl 2002, p. 214.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 122.

- ↑ Bartl 2002, pp. 30-31.

- 1 2 Bartl 2002, pp. 222., 233.

- ↑ Bartl 2002, p. 32.

- 1 2 3 Segeš 2011, p. 39.

- 1 2 Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 34.

- ↑ Segeš 2011, p. 44.

- ↑ Bartl 2002, p. 33.

- ↑ Segeš 2011, pp. 50-51.

- ↑ Bartl 2002, pp. 53-54.

- ↑ Segeš 2011, p. 50.

- ↑ Bartl 2002, pp. 222., 249.

- 1 2 Bartl 2002, p. 250.

- 1 2 Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 52.

- ↑ Bartl 2002, p. 45.

- 1 2 3 4 Kirschbaum 2005, p. 48.

- ↑ Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 53.

- ↑ Bartl 2002, p. 48.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 54.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 288.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, p. 67.

- ↑ Bartl 2002, pp. 50., 52.

- 1 2 3 4 Čičaj 2011, p. 72.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, p. 240.

- ↑ Daniel 1992, p. 56.

- 1 2 Daniel 1992, p. 58.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, p. xxiv.

- 1 2 Engel 2001, p. 370.

- ↑ Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 65.

- 1 2 Daniel 1992, p. 59.

- 1 2 Kirschbaum 2005, p. 62.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 371.

- ↑ Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 64.

- ↑ Daniel 1992, pp. 59-60.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2005, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 4 Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 Daniel 1992, p. 64.

- 1 2 Daniel 1992, p. 61.

- 1 2 Bartl 2002, p. 59.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, pp. 7., 134.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, p. 148.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, p. 68.

- 1 2 Daniel 1992, p. 60.

- 1 2 Murdoch 2000, p. 11.

- 1 2 3 4 Čičaj 2011, p. 73.

- 1 2 3 4 Bartl 2002, p. 61.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Čičaj 2011, p. 74.

- 1 2 Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 68.

- 1 2 Kowalská 2011, p. 91.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2005, p. 60.

- 1 2 Fahlbusch 2008, p. 38.

- ↑ Murdoch 2000, p. 12.

- ↑ Murdoch 2000, p. 15.

- ↑ Murdoch 2000, pp. 22-23.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, p. 293.

- 1 2 Kirschbaum 2005, p. 69.

- 1 2 Kirschbaum 2005, p. 74.

- 1 2 3 Bartl 2002, p. 64.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, p. 63.

- ↑ Murdoch 2000, pp. 27-28.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, p. 74.

- 1 2 3 Čičaj 2011, p. 75.

- ↑ Ingrao 2003, p. 31.

- 1 2 Bartl 2002, p. 66.

- ↑ Ingrao 2003, p. 33.

- ↑ Ingrao 2003, p. 40.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, p. 217.

- ↑ Bartl 2002, pp. 66-67.

- ↑ Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 70.

- ↑ Bartl 2002, p. 67.

- 1 2 Ingrao 2003, p. 41.

- 1 2 3 Čičaj 2011, p. 76.

- ↑ Bartl 2002, p. 68.

- 1 2 3 4 Čičaj 2011, p. 83.

- 1 2 Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 72.

- ↑ Bartl 2002, pp. 67., 203.

- 1 2 Čičaj 2011, p. 85.

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, p. 292.

- ↑ Bartl 2002, p. 69.

References

Primary sources

- Cosmas of Prague: The Chronicle of the Czechs (Translated with an introduction and notes by Lisa Wolverton) (2009). The Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-1570-9.

- Royal Frankish Annals (1972). In: Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard’s Histories (Translated by Bernhard Walter Scholz with Barbara Rogers) (1972); The University of Michigan Press; ISBN 0-472-06186-0.

- Simon of Kéza: The Deeds of the Hungarians (Edited and translated by László Veszprémy and Frank Schaer with a study by Jenő Szűcs) (1999). Central European University Press. ISBN 963-9116-31-9.

- The Life of Constantine (1983). In: Kantor, Marvin (1983); Medieval Slavic Lives of Saints and Princes; The University of Michigan Press; ISBN 0-930042-44-1.

- The Life of Methodius (1983). In: Kantor, Marvin (1983); Medieval Slavic Lives of Saints and Princes; The University of Michigan Press; ISBN 0-930042-44-1.

Secondary sources

- Barford, P. M. (2001). The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in Early Medieval Eastern Europe. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-3977-9.

- Bartl, Július (2002). Slovak History: Chronology & Lexicon. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 0-86516-444-4.

- Berend, Nora; Laszlovszky, József; Szakács, Béla Zsolt (2007). The kingdom of Hungary. In: Berend, Nora (2007); Christianization and the Rise of Christian Monarchy: Scandinavia, Central Europe and Rus', c. 900–1200; Cambridge University Press; ISBN 978-0-521-87616-2.

- Bowlus, Charles R. (1994). Franks, Moravians and Magyars: The Struggle for the Middle Danube, 788–907. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3276-3.

- Čaplovič, Dušan (2000). The area of Slovakia in the 10th century: development of settlement, interethnic and acculturation processes (focused on the area of northern Slovakia). In: Urbańczyk, Przemysłav; The Neighbours of Poland in the 10th century; Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences; ISBN 83-85463-88-7.

- Čičaj, Viliam (2011). The period of religious disturbances in Slovakia. In: Teich, Mikuláš; Kováč, Dušan; Brown, Martin D. (2011); Slovakia in History; Cambridge University Press; ISBN 978-0-521-80253-6.

- Daniel, David P. (1992). Hungary. In: Pettegree, Andrew (1992); The Early Reformation in Europe; Cambridge University Press; ISBN 0-521-39768-5.

- Fahlbusch, Erwin (2008).The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 5: Si–Z. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing & Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 978-0-8028-2417-2.

- Heather, Peter (2010). Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973560-0.

- Ingrao, Charles (2003). The Habsburg Monarchy, 1618–1815. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78505-1.

- Kirschbaum, Stanislav J. (2005). A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival. Palgrave. ISBN 1-4039-6929-9.

- Kirschbaum, Stanislav J. (2007). Historical Dictionary of Slovakia. The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5535-9.

- Kowalská, Eva (2011): The Enlightenment and the beginnings of the modern Slovak nation. In: Teich, Mikuláš; Kováč, Dušan; Brown, Martin D. (2011); Slovakia in History; Cambridge University Press; ISBN 978-0-521-80253-6.

- Lukačka, Ján (2011). The beginning of the nobility in Slovakia. In: Teich, Mikuláš; Kováč, Dušan; Brown, Martin D. (2011); Slovakia in History; Cambridge University Press; ISBN 978-0-521-80253-6.

- Mócsy, András (1974). Pannonia and Upper Moesia: A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. ISBN 0-7100-7714-9.

- Murdock, Graeme (2000). Calvinism on the Frontier, 1600-1660: International Calvinism and the Reformed Church in Hungary and Transylvania. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820859-4.

- Segeš, Vladimír (2011). Medieval towns. In: Teich, Mikuláš; Kováč, Dušan; Brown, Martin D. (2011); Slovakia in History; Cambridge University Press; ISBN 978-0-521-80253-6.

- Sommer, Petr; Třeštík, Dušan; Žemlička, Josef; Opačić, Zoë (2007). Bohemia and Moravia. In: Berend, Nora (2007); Christianization and the Rise of Christian Monarchy: Scandinavia, Central Europe and Rus’, c. 900–1200; Cambridge University Press; ISBN 978-0-521-87616-2.

- Spiesz, Anton; Caplovic, Dusan; Bolchazy, Ladislaus J. (2006). Illustrated Slovak History: A Struggle for Sovereignty in Central Europe. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 978-0-86516-426-0.

- Todd, Malcolm (2004). The Early Germans. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-1714-2.

- Urbańczyk, Przemysłav (2005). Early State Formation in East Europe. In: Curta, Florin; East Entral & Eastern Europe in the Early Middle Ages; The University of Michigan Press; ISBN 978-0-472-11498-6.

- Vlasto, A. P. (1970). The Entry of the Slavs into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-10758-7.