History of Western civilization before AD 500

Western civilization describes the development of human civilization beginning in the Near East, and generally spreading westwards. In its broader sense, its roots may be traced back to 9000 BCE, when humans existing in hunter-gatherer societies began to settle into agricultural societies. Farming became prominent around the headwaters of the Euphrates, Tigris and Jordan Rivers, spreading outwards into and across Europe; in this sense, the West produced the world's first cities, states, and empires.[1] However, Western civilization in its more strictly defined European sphere traces its roots back to European and Mediterranean classical antiquity. It can be strongly associated with nations linked to the former Western Roman Empire and with Medieval Western Christendom.

The civilizations of Classical Greece (Hellenic) and Roman Empire (Latin) as well as early Christendom are considered seminal periods in Western history; relevant contributions also came from the several civilizations of the Ancient Near East. From Ancient Greece sprang belief in democracy, and the pursuit of intellectual inquiry into such subjects as truth and beauty; from Rome came lessons in government administration, martial organization, engineering and law; and from Ancient Israel sprang Christianity with its ideals of the brotherhood of humanity. Strong cultural contributions also emerged from the pagan Germanic/Celtic/Slavic/Baltic and Nordic peoples of pre-Christian Europe. Following the 5th century Fall of Rome, Europe entered the Middle Ages, during which period the Catholic Church filled the power vacuum left in the West by the fallen Roman Empire, while the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire) endured for centuries.

Origins of the notion of "East" and "West"

The opposition of a European "West" to an Asiatic "East" has its roots in Classical Antiquity, with the Persian Wars where the Greek city states were opposing the expansion of the Achaemenid Empire. The Biblical opposition of Israel and Assyria from a European perspective was recast into these terms by early Christian authors such as Jerome, who compared it to the "barbarian" invasions of his own time (see also Assyria and Germany in Anglo-Israelism).

The "East" in the Hellenistic period was the Seleucid Empire, with Greek influence stretching as far as Bactria and India, besides Scythia in the Pontic steppe to the north. In this period, there was significant cultural contact between the Mediterranean and the East, giving rise to syncretisms like Greco-Buddhism. The establishment of the Byzantine Empire around the 4th century established a political division of Europe into East and West and laid the foundations for divergent cultural directions, confirmed centuries later with the Great Schism between Eastern Orthodox Christianity and Roman Catholic Christianity.

The Mediterranean and the Ancient West

The earliest civilizations which influenced the development of the West were those of Mesopotamia, the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran: the cradle of civilization. An agricultural revolution began here around 10,000 years ago with the domestication of animals like sheep and goats and the appearance of new wheat hybrids, notably bread wheat, at the completion of the last Ice Age, which allowed for a transition from nomadism to village settlements and then cities like Jericho.[2]

The Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians and Assyrians all flourished in this region. Soon after the Sumerian civilization began, the Nile River valley of ancient Egypt was unified under the Pharaohs in the 4th millennium BC, and civilization quickly spread through the Fertile Crescent to the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea and throughout the Levant. The Phoenicians, Israelites and others later built important states in this region.

The ancient peoples of the Mediterranean heavily influenced the origins of Western civilisation. The Mediterranean Sea provided reliable shipping routes linking Asia, Africa and Europe along which political and religious ideas could be traded along with raw materials such as timber, copper, tin, gold and silver as well as agricultural produce and necessities such as wine, olive oil, grain and livestock. By 3100BC, the Egyptians were employing sails on boats on the Nile River and the subsequent development of the technology, coupled with knowledge of the wind and stars allowed naval powers such as the Phoenicians, Greeks, Carthaginians and Romans to navigate long distances and control large areas by commanding the sea. Cargo galleys often also employed slave oarsmen to power their ships and slavery was an important feature of the ancient Western economy.[3]

Thus, the great ancient capitals were linked — cities such as: Athens, home to Athenian democracy, and the Greek philosophers Aristotle, Plato and Socrates; the city of Jerusalem, the Jewish capital, where Jesus of Nazareth preached and was executed around AD 30; and the city of Rome, which gave rise to the Roman Empire which encompassed much of Europe and the Mediterranean. Knowledge of Greek, Roman and Judeo-Christian influence on the development of Western civilization is well documented because it attached to literate cultures, however, Western history was also strongly influenced by less literate groups such as the Germanic, Scandinavian and Celtic peoples who lived in Western and Northern Europe beyond the borders of the Roman world. Nevertheless, the Mediterranean was the centre of power and creativity in the development of ancient Western civilisation. Around 1500 BC, metallurgists learned to smelt iron ore, and by around 800BC, iron tools and weapons were common along the Aegean Sea, representing a major advance for warfare, agriculture and crafts in Greece.[3]

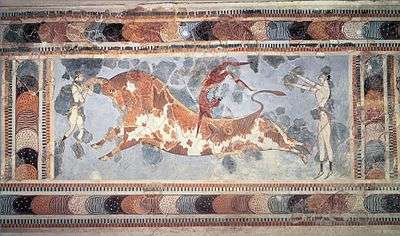

The earliest urban civilizations of Europe belong to the Bronze Age Minoans of Crete and Mycenaean Greece, which ended around the 11th century BC as Greece entered the Greek Dark Ages.[4] Ancient Greece was the civilization belonging to the period of Greek history lasting from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to 146 BC and the Roman conquest of Greece after the Battle of Corinth. Classical Greece flourished during the 5th to 4th centuries BC. Under Athenian leadership, Greece successfully repelled the military threat of Persian invasion at the battles of Marathon and Thermopylae. The Athenian Golden Age ended with the defeat of Athens at the hands of Sparta in the Peloponnesian War in 404 BC.

By the 6th century BC, Greek colonists had spread far and wide — from the Russian Black Sea coast to the Spanish Mediterranean and through modern Italy, North Africa, Crete, Cyprus and Turkey. The Ancient Olympic Games are said to have begun in 776BC and grew to be a major cultural event for the citizens of the Greek diaspora, who met every four years to compete in such sporting events as running, throwing, wrestling and chariot driving. Trade flourished and by 670BC the barter economy was being replaced by a money economy, with Greeks minting coins in such places as the island of Aegina. Poultry arrived from India around 600BC and would grow to be a European staple. The Hippocratic Oath, historically taken by doctors swearing to practice medicine ethically, is said to have been written by the Greek Hippocrates, often regarded as the father of western medicine, in Ionic Greek (late 5th century BC),[5]

The Greek city states competed and warred with each other, with Athens rising to be the most impressive. Learning from the Egyptians, Athenian art and architecture shone from 520 to 420BC and the city completed the Parthenon around 447BC to house a statue of their city goddess Athena. The Athenians also experimented with democracy. Property owners assembled almost weekly to make speeches and instruct their temporary rulers: a council of 500, chosen by lot or lottery, whose members could only serve a total of 2 years in a lifetime, and a smaller, high council from whom one man was selected by lottery to preside from sunset to the following sunset.[3]

Thus, the citizens' assembly shared power and prevented lifetime rulers from taking control. Military chiefs were exempt from the short term requirement however and were elected, rather than chosen by lot. Eloquent oratory became a Greek art form as speakers sought to sway large crowds of voters. Athenians believed in 'democracy' but not in equality and excluded women, slaves, the poor and foreign from the assembly. Notions of a general "brotherhood of man" were yet to emerge.[3]

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC and continued through the Hellenistic period, at which point Ancient Greece was incorporated into the Roman Empire. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including political philosophy, ethics, metaphysics, ontology, logic, biology, rhetoric, and aesthetics. Plato was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician and writer of philosophical dialogues. He was the founder of the Academy in Athens which was the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Inspired by the admonition of his mentor, Socrates, prior to his unjust execution that "the unexamined life is not worth living", Plato and his student, the political scientist Aristotle, helped lay the foundations of Western philosophy and science.[6] Plato's sophistication as a writer is evident in his Socratic dialogues.

In classical tradition, Homer is the ancient Greek epic poet, author of the Iliad, the Odyssey and other works. Homer's epics stand at the beginning of the western canon of literature, exerting enormous influence on the history of fiction and literature in general.

Alexander the Great (356BC-323BC) was a Greek king of Macedon and the creator of one of the largest empires in ancient history. He was tutored by the philosopher Aristotle and, as ruler, broke the power of Persia, overthrew the Persian king Darius III and conquered the Persian Empire.ii[›] His Macedonian Empire stretched from the Adriatic sea to the Indus river. He died in Babylon in 323 BC and his empire did not long survive his death. Nevertheless, the settlement of Greek colonists around the region had long lasting consequence and Alexander features prominently in Western history and mythology.[7]

The city of Alexandria in Egypt, which bears his name and was founded in 330BC, became the successor to Athens as the intellectual cradle of the Western World. The city hosted such leading lights as the mathematician Euclid and anatomist Herophilus; constructed the great Library of Alexandria; and translated the Hebrew Bible into Greek (called the Septuagint for it was the work of 70 translators).[3]

The ancient Greeks excelled in engineering, science, logic, politics and medicine. Classical Greek culture had a powerful influence on the Roman Empire, which carried a version of it to many parts of the Mediterranean region and Europe, for which reason Classical Greece is generally considered to be the seminal culture which provided the foundation of Western civilization.[8][9][10]

Ancient Rome was a civilization that grew out of a small agricultural community, founded on the River Tiber, on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 10th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea, and centered at the city of Rome, the Roman Empire became one of the largest empires in the ancient world.[11] In its centuries of existence, Roman civilization shifted from a monarchy to an oligarchic republic to an increasingly autocratic empire. It came to dominate South-Western Europe, South-Eastern Europe/the Balkans and the Mediterranean region through conquest and assimilation.

Originally ruled by Kings who ruled the settlement and a small area of land nearby, the Romans established a republic in 509BC that would last for five centuries. Initially a small number of families shared power, later representative assemblies and elected leaders ruled. Rome remained a minor power on the Italian peninsula, but found a talent for producing soldiers and sailors and, after subduing the Sabines, Etruscans and Piceni began to challenge the power Carthage. By 240BC, Rome controlled the formerly Greek controlled island of Sicily. Following the 207BC defeat of the bold Carthaginian general Hannibal, who had led an army spearheaded by war elephants over the Alps into Italy, the Romans were able to expand their overseas empire into North Africa. Roman engineers built arterial roads throughout their empire, beginning with the Appian Way through Italy in 312BC. Along such roads marched soldiers, merchants, slaves and citizens to all corners of a flourishing mercantile empire. Roman engineering was so formidable that roads, bridges and aqueducts survive in impressive scale and quantity to the present day. According to the historian Geoffrey Blainey, the population of the Imperial capital was probably the first in the world to approach one million people. It eventually consisted of monumental public buildings, such as the Colosseum (dedicated to sport), the bathhouses (dedicated to leisure) and the Roman Forum dedicated to civic affairs. Slavery helped power the economy, but also created occasional tension — as in the slave rebellion led by Spartacus which was put down in 71BC.[3]

Julius Caesar (100BC-44BC) was a Roman general and statesman who played a critical role in the gradual transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. Conspirators who feared he was seeking to re-establish a monarchy assassinated him on the floor of the Roman Senate in 44BC. His anointed successor Augustus Caesar outmaneuvered his opponents to reign as a de facto emperor from 27BC. His successors became all-powerful and demanded veneration as gods. Rome entered its period of Imperial rule and stability (albeit often marred by occasional bouts of apparent insanity by various god-emperors) returned to the Empire.[3]

Roman civilization and history contributed greatly to the development of government, law, war, art, literature, architecture, technology, religion, and language in the Western world. Ecclesiastical Latin, the Roman Catholic Church’s official language, remains a living legacy of the classical world to the contemporary world but the Classical languages of the Ancient Mediterranean influenced every European language, imparting to each a learned vocabulary of international application. It was, for many centuries, the international lingua franca and Latin itself evolved into the Romance languages, while Ancient Greek evolved into Modern Greek. Latin and Greek continue to influence English, not least in the specialised vocabularies of science, technology and the law.

Judaism and the rise of Christendom

Judaism claims a historical continuity spanning around 4000 years. Originally herders, who probably originated from the Persian Gulf or nearby deserts, the Hebrews (the name signified 'wanderer')[3] formed one of the most enduring monotheistic religions,[12] and the oldest to survive into the present day.[13][14] Abraham is traditionally considered as the father of the Jewish people, and Moses the law giver, who, according to the Hebrew Bible, led them out of slavery in Egypt and delivered them to the "Promised Land" of Israel. While the historicity of these accounts is not considered precise, the stories of the Hebrew Bible have been an inspiration for vast quantities of Western art, literature and scholarship.

Around 1000BC, the Israelites had a period of power under King David who captured Jerusalem. His son King Solomon constructed the first magnificent Temple at Jerusalem for the worship of God. The Jews rejected the polytheism common to that age and would worship only God, whose Ten Commandments instructed them on how to live. These commandments remain influential in the West and prohibited theft, lying and adultery; called for worship of only one God; and for respect and honour for parents and neighbours. The Jews observed Sabbath as a "day of rest" (called "one of the first wide-ranging laws of social-welfare in the world" by the historian Geoffrey Blainey). In 587BC, the Neo-Babylonian Empire of Nebuchadnezzar II destroyed the Temple and the Jewish leaders went into exile to return a century later to face a succession of foreign rulers: Persian and Greek.[3] Judaism's texts, traditions and values play a major role in later Abrahamic religions, including Christianity, Islam and the Baha'i Faith.[14][15] Many aspects of Judaism have also influenced secular Western ethics and law.[16]

In 63BC, Judea became part of the Roman Empire and, around 6BC Jesus was born to a Jewish family in the town of Nazareth, as a consequence of which, worship of the god of Israel would come to spread through, and later dominate, the Western World.[3] Later the Western calendar would be divided into Before Christ (BC) (meaning before Jesus was born) and Anno Domini (AD).

Christianity began as a Jewish sect in the mid-1st century arising out of the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. The life of Jesus is recounted in the New Testament of the Bible, one of the bedrock texts of Western Civilisation.[17] According to the New Testament, Jesus was raised as the son of the Nazarenes Mary (called the "Blessed Virgin" and "Mother of God") and her husband Saint Joseph (a carpenter). Jesus' birth is commemorated in the festival of Christmas. Jesus learned the texts of the Hebrew Bible and like his contemporary John the Baptist, became an influential wandering preacher. He gathered Twelve Disciples to assist in his work. He was a persuasive teller of parables and moral philosopher. In orations such as his Sermon on the Mount and stories such as The Good Samaritan and his declaration against hypocrisy "Let he who is without sin cast the first stone", Jesus called on followers to worship God, act without violence or prejudice and care for the sick, hungry and poor. He criticized the privilege and hypocrisy of the religious establishment which drew the ire of religious and civil authorities, who persuaded the Roman Governor of the province of Judaea, Pontius Pilate, to have him executed for subversion. In Jerusalem, around AD 30 Jesus was crucified (nailed alive to a wooden cross) and died.[3] According to the Bible, his body disappeared from his tomb three days later, because he had been resurrected from the dead. The festival of Easter recalls this event.

The early followers of Jesus, including Saints Paul and Peter carried a new theology concerning him throughout the Roman Empire and beyond, sowing the seeds of such institutions as the Catholic Church, of which Saint Peter is remembered as the first Pope. Saint Paul, in particular, emphasised the universality of the faith and the religion moved beyond the Jewish population of the Empire and Asia Minor. Later Jesus was called "Christ" (meaning "anointed one" in Greek), and thus his followers became known as Christians. Christians often faced persecution from authorities or antagonistic populations during these early centuries, particularly for their refusal to join in worshiping the emperors. The Emperor Nero famously blamed them for the Great Fire of Rome in AD 64 and condemned them to Damnatio ad bestias, a form of capital punishment in which people were maimed to death by animals in the circus arena.[3]

Nevertheless, carried through the synagogues, merchants and missionaries across the known world, the new religion quickly grew in size and influence. Emperor Constantine's Edict of Milan in AD 313 ended the persecutions and his own conversion to Christianity was a significant turning point in history.[18] In AD 325, Constantine conferred the First Council of Nicaea to gain consensus and unity within Christianity, with a view to establishing it as the religion of the Empire. The council composed the Nicean Creed which outlined a profession of the Christian faith. Constantine instigated Sunday as Sabbath and "day of rest" for Roman society (though initially this was only for urban dwellers).

The population and wealth of the Roman Empire had been shifting east, and the division of Europe into a Western (Latin) and an Eastern (Greek) part was prefigured in the division of the Empire by the Emperor Diocletian in AD 285. Around 330, Constantine established the city of Constantinople as a new imperial city which would be the capital of the Byzantine Empire. Possessed of mighty fortifications and architectural splendour, the city would stand for another thousand years as a "Roman Capital". The Hagia Sophia Cathedral (later converted to a mosque following the Fall of Constantinople in 1453) is one of the greatest surviving examples of Byzantine architecture, with its vast dome and interior of mosaics and marble pillars, it was so richly decorated that the Emperor Justinian, the last emperor to speak Latin as a first language, is said to have proclaimed upon its completion in 562: "Solomon, I have surpassed thee!".

The city of Rome itself never regained supremacy and was sacked by the Visigoths in 410 and the Vandals in 455. Although cultural continuity and interchange would continue between these Eastern and Western Roman Empires, the history of Christianity and Western culture took divergent routes, with a final Great Schism separating Roman and Eastern Christianity in 1054.

When the Western Roman Empire was starting to disintegrate, St Augustine was Bishop of Hippo Regius.[19] He was a Latin-speaking philosopher and theologian who lived in the Roman Africa Province. His writings were very influential in the development of Western Christianity and he developed the concept of the Church as a spiritual City of God (in a book of the same name), distinct from the material Earthly City.[20] His book Confessions, which outlines his sinful youth and conversion to Christianity, is widely considered to be the first autobiography written in the canon of Western Literature. Augustine profoundly influenced the coming medieval worldview.[21]

Fall of Rome

In 476 the western Roman Empire, which had ruled modern-day Italy, France, Spain, Portugal and England for centuries, collapsed due to a combination of economic decline, and drastically reduced military strength which allowed invasion by barbarian tribes originating in southern Scandinavia and modern-day northern Germany. Historical opinion is divided as to the reasons for the Fall of Rome, but the societal collapse encompassed both the gradual disintegration of the political, economic, military, and other social institutions of Rome as well as the barbarian invasions of Western Europe.

In England, several Germanic tribes invaded, including the Angles and Saxons. In Gaul (modern-day France, Belgium and parts of Switzerland) and Germania Inferior (The Netherlands), the Franks settled, in Iberia the Visigoths invaded and Italy was conquered by the Ostrogoths.

The slow decline of the Western Empire occurred over a period of roughly three centuries, culminating in 476, when Romulus Augustus, the last Emperor of the Western Roman Empire, was deposed by Odoacer, a Germanic chieftain. Some modern historians question the significance of this date,[22] and not simply because Julius Nepos, the legitimate emperor recognized by the East Roman Empire, continued to live in Salona, Dalmatia, until he was assassinated in 480. More importantly, the Ostrogoths who succeeded considered themselves upholders of the direct line of Roman traditions and, as the historian Edward Gibbon noted, the Eastern Roman Empire continued until the Fall of Constantinople on May 29, 1453.

See also

- Western world

- Western culture

- History of citizenship

- History of Europe

- Modern history

- Role of the Catholic Church in Western civilization

References

- ↑ Morris, Ian."Location, location and how the West was won", BBC News Magazine, 10 November 2010.

- ↑ Jacob Bronowski; The Ascent of Man; Angus & Robertson, 1973 ISBN 0-563-17064-6

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Geoffrey Blainey; A Very Short History of the World; Penguin Books, 2004

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/A765146-54

- ↑ The Hippocratic oath: text, translation and interpretation By Ludwig Edelstein Page 56 ISBN 978-0-8018-0184-6 (1943)

- ↑ "Plato". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2002.

- ↑ Yenne, W. Alexander the Great: Lessons from History's Undefeated General. Palmgrave McMillan, 2010. 244 p.

- ↑ Richard Tarnas, The Passion of the Western Mind (New York: Ballantine Books, 1991).

- ↑ Colin Hynson, Ancient Greece (Milwaukee: World Almanac Library, 2006), 4.

- ↑ Carol G. Thomas, Paths from Ancient Greece (Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1988).

- ↑ Chris Scarre, The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Rome (London: Penguin Books, 1995).

- ↑ "Religion & Ethics — Judaism". BBC. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "Judaism" (PDF). (52.1 KB)

- 1 2 "The 3 Monotheistic Religions — Essays — Noel12". StudyMode.com. 2008-05-26. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "Judaism page, Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance". Religioustolerance.org. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ Jewish Contributions to Civilization: An Estimate (book)

- ↑ BBC, BBC—Religion & Ethics—566, Christianity

- ↑ Religion in the Roman Empire, Wiley-Blackwell, by James B. Rives, page 196

- ↑ "Bona, Algeria". World Digital Library. 1899. Retrieved 2013-09-25.

- ↑ Durant, Will (1992). Caesar and Christ: a History of Roman Civilization and of Christianity from Their Beginnings to A.D. 325. New York: MJF Books. ISBN 1-56731-014-1.

- ↑ Wilken, Robert L. (2003). The Spirit of Early Christian Thought. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 291. ISBN 0-300-10598-3.

- ↑ Arnaldo Momigliano, echoing the trope of the sound a tree falling in the forest, titled an article in 1973, "La caduta senza rumore di un impero nel 476 d.C." ("The noiseless fall of an empire in AD 476").

Further reading

- Bavaj, Riccardo: "The West": A Conceptual Exploration , European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2011, retrieved: November 28, 2011.

- Atlas of World Military History, ISBN 0-7607-2025-8, edited by Richard Brooks

- Almanac of World History by Patricia S. Daniels and Stephen G. Hyslop

- The Millennium Time Tapestry ISBN 0-918223-04-0 by Matthew Hurff

- The Earth and its Peoples ISBN 0-618-42765-1, edited by Jean L. Woy

- Greek Ways: How the Greeks Created Western Civilization by Bruce Thornton, Encounter Books, 2002

- How the Irish Saved Civilization: The Untold Story of Ireland's Heroic Role from the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Medieval Europe by Thomas Cahill, 1995.

Further media

- Civilisation: A Personal View by Kenneth Clark (TV Series), BBC TV, 1969.

- The Ascent of Man (TV series), presented by Jacob Bronowski, BBC TV, 1973.