History of the Toronto Maple Leafs

This is a history of the Toronto Maple Leafs of the National Hockey League.

| Part of the series on | ||||||||||

| Evolution of the Toronto Maple Leafs | ||||||||||

| Teams | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Ice hockey portal · |

Early years (1917–1928)

The beginnings of the Maple Leafs NHL franchise arose out of a long-running dispute between Eddie Livingstone, owner of the National Hockey Association's Toronto Blueshirts, and his fellow NHA owners. By the fall of 1917, the owners of the NHA's other four clubs—the Montreal Canadiens, Montreal Wanderers, Ottawa Senators, and Quebec Bulldogs—were eager to disassociate themselves from Livingstone. They soon discovered the NHA's constitution didn't allow them to simply vote Livingstone out. With this in mind, they met in Montreal on November 22 and created a new league—the National Hockey League. However, they didn't invite Livingstone to join them, effectively leaving him in a one-team league. On paper, they also remained members of the NHA and were able to vote down Livingstone's attempts to keep that league operating.

Torontos/Arenas (1917–1919)

However, the other clubs and arena owners felt it would be unthinkable not to have a team from Toronto (Canada's second-largest city at the time) in the new league. Also, the new league needed a fourth team to balance the schedule because the Bulldogs had run into financial trouble and opted to suspend operations (as it turned out, they wouldn't ice a team until 1920). Accordingly, the new league granted a 'temporary' franchise for Toronto to the Toronto Arena Company, owners of the Mutual Street Arena (also known as the Arena Gardens), to use the Blueshirts' players for the season until the dispute with Livingstone could be resolved. The Arena would handle the settlement with Livingstone out of the club revenues. Under manager Charlie Querrie and coach Dick Carroll, the Toronto team won the Stanley Cup in the NHL's inaugural season. The team actually did not have an official name during that season, but was still unofficially called "the Blueshirts" and "the Torontos" by the newspapers of the day, as well as by some fans. Although the roster was composed mainly of former Blueshirts, the Maple Leafs do not claim the Blueshirts' history as their own.

In 1918, the NHA voted once again against playing and the other owners made plans to operate the NHL for a second season. Since the Torontos had won the Cup, even more revenue was at stake and Livingstone held out for $20,000, though the Arena offered $6,000. This led to Livingstone filing another lawsuit, this against the Arena Company. In response, instead of returning the players to Livingstone, or even paying Livingstone, the Arena Company returned its temporary franchise to the NHL and immediately formed a new club, the Toronto Arena Hockey Club, popularly known as the Toronto Arenas, with auditor Hubert Vearncombe as team president. The new club was a self-contained corporation within the Arena Company's corporate structure, and could thus exist separate from any legal action. This new club immediately applied for membership in the NHL, and was duly admitted as a full member in good standing. (The Maple Leafs themselves say they were known as the Arenas during their first season,[1] but the name "Arenas" was not recorded to commemorate the team's 1918 Cup victory until 1947.) At the same time, the Arena Company board decided that only NHL teams would be allowed to play at the Arena Gardens, effectively foreclosing Livingstone's efforts to resurrect the NHA.[2] Livingstone's suit dragged through the courts for nearly a decade. Although the courts ultimately decided in his favour, he never got his team back.

Mounting legal bills from the dispute forced the Arenas to sell most of their stars, resulting in a horrendous five-win season in 1918–19. With the club losing money and no hope of catching Ottawa and Montreal in the standings in a three-team league, they requested permission to suspend operations in late February 1919. League president Frank Calder persuaded the team to play its 18th game on February 20, after which the league ended the regular season and immediately proceeded to the playoffs. The Arenas' .278 winning percentage that season is still the worst in franchise history. However, since the 1919 Stanley Cup Finals ended without a winner, the Arenas proclaimed themselves world champions by default.

Toronto St. Pats (1919–1927)

In 1919, Livingstone won a $20,000 judgement against the Arena Company, which promptly declared bankruptcy to avoid paying. The Toronto NHL franchise was put up for sale and Querrie put together a group that mainly consisted of the people who had run the senior amateur St. Patricks team in the Ontario Hockey Association the previous year.

The new owners renamed the team the Toronto St. Patricks (or St. Pats for short). Among the officers of the St. Patrick's Professional Hockey Club Ltd. at the start of the 1919–20 season were president Fred Hambly, vice-president Paul Ciceri, secretary-treasurer Harvey Sproule, Charlie Querrie, and player-coach Frank Heffernan. The jersey colour was changed from blue to green.

The 1921–22 NHL season led to the St. Pat's only Stanley Cup win. The team finished second to the Ottawa Senators, but caught fire in the playoffs. The St. Pats defeated the Senators in a two-game total goals series 5–4. The team then traveled to Vancouver to take on the Millionaires, winning the series 3–2 and the Cup. (see 1922 Stanley Cup Finals). The team was led by Babe Dye who scored 11 goals in the 7 playoff games, and John Ross Roach who had two shutouts.

The next two seasons the St. Pats did not make the playoffs, but qualified second in 1924–25, which had expanded the number of qualifiers to three as the Maroons and Bruins joined as expansion franchises. This meant a playoff with the Canadiens with the winner to play the Hamilton Tigers, the regular season champion. The St. Pats were defeated in what turned out to be the league finals as the Tigers were suspended. The next two seasons the St. Pats did not make the playoffs.

During the mid-1920s, the St. Pats allowed other teams to use the Mutual Street Arena in the early and late months of the season, when it was usually too warm for proper ice. The Arena was the only facility east of Manitoba with artificial ice.[2]

The Conn Smythe era

Querrie lost a lawsuit to Livingstone and decided to put the St. Pats up for sale. He gave serious consideration to a $200,000 bid from a Philadelphia group. However, Toronto Varsity Graduates coach Conn Smythe put together an ownership group of his own and made a $160,000 offer for the franchise. With the support of St. Pats shareholder J. P. Bickell, Smythe persuaded Querrie to reject the Philadelphia bid, arguing that civic pride was more important than money.

After taking control on Valentine's Day 1927 Smythe immediately renamed the team the Maple Leafs. (The Toronto Maple Leafs baseball team had won the International League championship a few months earlier and had been using that name for 30 years.) There have been numerous reasons cited for Smythe's decision to rename the team. The Maple Leafs say that the name was chosen in honour of the Maple Leaf Regiment from World War I. Another story says that Smythe named the team after a team he'd once scouted, called the East Toronto Maple Leafs.

Smythe's name was initially kept in the background, even though he was the largest shareholder. When the newly renamed Toronto Maple Leaf Hockey Club Ltd. promoted a public share offering to raise capital, it only disclosed that "one of the most prominent hockey coaches in Toronto" would be taking over management of the club.[3] That prominent coach turned out to be Smythe, who installed himself as general manager.

Initial reports were that the team's colours would be changed to red and white,[4] but the Leafs were wearing white sweaters with a green maple leaf for their first game on February 17, 1927.[5] The next season, the Leafs appeared for the first time in the blue and white sweaters they have worn ever since. While the Leafs say that blue represents the Canadian skies and white represents snow, it is also true that top-level Toronto teams have worn blue since the Toronto Argonauts adopted blue as their primary colour in 1873. Another theory is that Smythe changed the colours as a nod to his high school alma mater, Upper Canada College, whose teams have worn blue and white since 1829 and the University of Toronto whose teams have also worn blue and were called the Varsity Blues.[6]

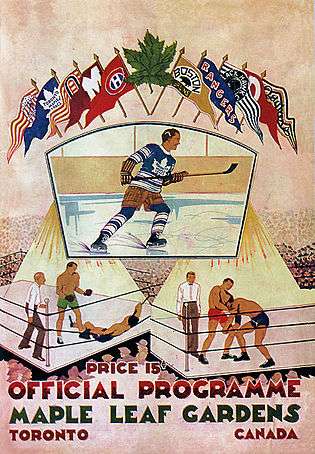

After four more lacklustre seasons (including three with Smythe as coach), Smythe and the Leafs debuted their new arena, Maple Leaf Gardens, with a 2–1 loss to the Chicago Blackhawks on November 12, 1931. Led by the "Kid Line" (Busher Jackson, Joe Primeau and Charlie Conacher) and coach Dick Irvin, the Leafs would capture their third Stanley Cup victory during the first season in their new digs. They would go the distance in 1932, vanquishing Charlie Conacher's older brother Lionel Conacher and his Montreal Maroons in the first round, then in the semi-finals against the Boston Bruins, winning in the sixth overtime of the final game, and would not be overwhelmed in the Stanley Cup Finals by the hated New York Rangers. Smythe took particular pleasure in defeating the Rangers that year; he had been tapped as the Rangers' first general manager and coach in the Rangers' inaugural season (1926–27), but had been fired in a dispute with Madison Square Garden management. the next season, only to be upended by the Rangers.

The Leafs' star forward, Ace Bailey, was nearly killed in 1933 when Boston Bruins defenceman Eddie Shore checked him from behind into the boards at full speed. Maple Leafs defenceman Red Horner was able to knock Shore out with a punch, but it was too late for Bailey, who was by now writhing on the ice, had his career ended. Undeterred, the Leafs would reach the finals five more times in the next seven years, but would not win, bowing out to the now-defunct Maroons, the Detroit Red Wings in 1936, the Chicago Black Hawks in 1938, Boston in 1939, and the hated Rangers in 1940. After the 1940 loss, Smythe talked the then-moribund Canadiens into hiring Irvin as coach. Irvin was replaced in Toronto by former Leafs captain Hap Day. Toronto looked sure to suffer a similar fate in 1942, down three games to none in a best-of-seven final in 1942 against Detroit. However, fourth-line forward Don Metz would galvanize the team, coming from nowhere to score a hat-trick in game four and the game-winning goal in game five, with the Leafs winning both times. Captain Syl Apps had won the Lady Byng Memorial Trophy that season, not taking one penalty and finishing his ten-season career with an average of 5 minutes, 36 seconds in penalties a season. Goalie Turk Broda would shut out the Wings in game six, and Sweeney Schriner would score two goals in the third period to win the seventh game 3–1 and the stanley cup. No other team has repeated a comeback like this in a stanley cup final since.

Apps told writer Trent Frayne in 1949, "If you want me to be pinned down to my [biggest night in hockey but also my] biggest second, I'd say it was the last tick of the clock that sounded the final bell. It's something I shall never forget at all." It was the first time a major pro sports team came back from behind 3–0 to win a best-of-seven championship series.

Three years later, with their heroes from 1942 dwindling (due to either age, health, or the war), the Leafs turned to lesser-known players like rookie goalie Frank McCool and defenceman Babe Pratt. They would upset the Red Wings in the 1945 finals. In the 1946-47 NHL season, Maple Leaf Gardens was the first arena in the NHL to have Plexiglas inserted in the end zones of the rink.[7]

The powerful defending champion Montreal Canadiens and their "Punch Line" (Maurice "Rocket" Richard, Toe Blake and Elmer Lach) would be the Leafs' nemesis two years later when the two teams clashed in the 1947 finals. Ted "Teeder" Kennedy would score the game-winning goal late in game six to win the Leafs their first of three straight Cups — the first time any NHL team had accomplished that feat. With their Cup victory in 1948, the Leafs moved ahead of Montreal for the most Stanley Cups in franchise history. It would take the Canadiens 10 years to reclaim the record.

The Leafs and Habs would meet once again in the finals in 1951, with all five games going to overtime. Tod Sloan scored with 42 seconds left in the third period of game five to send it to an extra period, and defenceman Bill Barilko, who had scored only six goals in the regular season, scored the game-winner to win Toronto their fourth Cup in five years. Barilko's glory, however, was short-lived: he disappeared in a plane crash near Timmins, Ontario, barely four months after that historic moment. Barilko's legacy is still remembered over 50 years later, and The Tragically Hip's song "Fifty Mission Cap" is based on his plight.

New owners, new dynasty in the 1960s

Toronto was unable to match up with their Cup-winning teams of the 1940s and 1951 for a long time, and stronger teams like Detroit and Montreal won the Cup year after year. In fact, the Habs' 1950s dynasty closed with a last-round Maple Leaf sweep. They did not win another Stanley Cup until 1962.

Before the 1961–62 season, Smythe sold nearly all of his shares in Maple Leaf Gardens to a partnership of his son Stafford Smythe, newspaper baron John Bassett and Toronto Marlboros president Harold Ballard. The sale price was $2.3 million—a handsome return on his original investment 34 years earlier. According to Stafford's son Thomas, Conn Smythe said years later that he expected to sell his shares only to his son and would not have sold his shares to the partnership.[8] However, it is not likely that Conn Smythe could have believed that Stafford could have raised the money needed to make the deal on his own. This purchase gave the three control of about 60% ownership of the Leafs and Gardens.

And then, Toronto was able to reel off another three straight Stanley Cup victories from 1962 to 1964, with the help of Hall of Famers Frank Mahovlich, Red Kelly, Johnny Bower, Dave Keon, Andy Bathgate and Tim Horton, and under the leadership of coach and general manager Punch Imlach. However, Bathgate claimed after 1964–65 that all the autocratic Imlach said to himself and Mahovlich was insulting:

“Imlach never spoke to Frank Mahovlich or myself for most of the season, and when he did, it was to criticize. Frank usually got the worst. We are athletes, not machines, and Frank is the type that needs some encouragement, a pat on the shoulder every so often.”[9]

It was Bathgate's one-way ticket to the floundering Red Wings, but Toronto would, for a few more years, keep "The Big M."

In 1967, the Leafs and Canadiens met in the Cup finals for the last time. Montreal was considered to be a heavy favourite as analysts said that the Leafs were just a bunch of has-beens. But Bob Pulford scored the double-overtime winner in game three, Jim Pappin got the series winner in game six, and Keon won the Conn Smythe Trophy as Most Valuable Player of the playoffs as the Maple Leafs won the Stanley Cup in six games. The Leafs have not won the Stanley Cup since.

The next two seasons saw a great deal of turnover, engineered by Imlach, who detested the new Players' Association headed by Maple Leaf players. Bobby Baun and Kent Douglas were left unprotected in the expansion draft. In 1968, Mahovlich was traded to Detroit in a blockbuster trade.

But there was no improvement in the team. After a disastrous first-round playoff loss to Boston in 1969, Smythe fired Imlach.

The Ballard years

Following Stafford Smythe's death, Harold Ballard bought Stafford Smythe's shares, taking control of the team as of February, 1972, under terms of Stafford Smythe's will, allowing each partner to buy the other's shares upon their death. Stafford Smythe's brother Hugh also sold his shares to Ballard, ending the Smythe family's 45-year involvement in the NHL. Stafford Smythe's son Thomas alleges that Ballard wrote the will to his advantage.[10]

One of the most detested owners in NHL history, he traded away many of the team's most popular players. He also blocked Keon from signing with another NHL team when his contract ran out in 1975, forcing him to jump to the Minnesota Fighting Saints of the World Hockey Association. Ballard assumed (correctly) that the Leafs would continue to sell out regardless of the team's on-ice quality, and refused to raise the payroll any higher than necessary to be profitable.

During the 1970s, with the overall level of talent in the league diluted by the addition of 12 new franchises and the rival WHA, the Leafs, led by a group of stars such as Darryl Sittler, Lanny McDonald, enforcer Tiger Williams, Ian Turnbull and Borje Salming were able to ice competitive teams for several seasons. On February 7, 1976, Sittler would score six goals and four assists against the Bruins to establish an NHL single-game record that still stands more than 30 years later. On February 2, 1977, Toronto Maple Leafs defenceman Ian Turnbull would be the first player in NHL history to score five goals on five shots.[11] Despite the performances, the Leafs were not able to qualify for the Stanley Cup Finals. They only once made it past the second round of the playoffs, besting the New York Islanders, a soon-to-be dynasty, in the 1978 quarter-finals, only to be swept by their arch-rivals the Montreal Canadiens, in the semi-finals.

In July 1979, Ballard brought Imlach, a longtime friend, back to the organization as GM. When the Leafs traded McDonald, a close friend of Sittler, to the moribund Colorado Rockies on December 29, 1979; a member of the Leafs anonymously told the Toronto Star that Ballard and Imlach would "do anything to get at Sittler"[12] and traded McDonald to undermine Sittler's influence on the team. Sittler, along with other Leafs who were members of the NHL Players' Association, was agitating for a better contract. Angry teammates trashed their dressing room in response, and Sittler temporarily resigned his captaincy. NHL executive director Alan Eagleson, who was also Sittler's agent, called the trade "a classless act."[12] Sittler himself was gone two years later, when the Leafs traded him to the Philadelphia Flyers. He left as the franchise's all-time leading scorer.

The McDonald trade sent the Leafs into a downward spiral. They finished five games under .500 and only made the playoffs due to the presence of the Quebec Nordiques, a refugee from the WHA, in the Adams Division. Ironically, Ballard had opposed taking the Nordiques and three other WHA teams into the NHL for the start of the 1979–80 season. He had never forgiven the WHA for nearly decimating his roster in the early 1970s, and the addition of three Canadian teams (the Nordiques, Winnipeg Jets and Edmonton Oilers) significantly reduced the Leafs' revenue from Hockey Night in Canada broadcasts (which was now split six ways rather than three).

For the next 12 years, the Leafs were barely competitive, not posting another winning record until 1992–93. They missed the playoffs six times and only finished above fourth in their division once (in 1990, the only season where they even posted a .500 record). They only made it beyond the first round of the playoffs twice (in 1986 and 1987, advancing to the division finals). The low point came in 1984–85, when they finished 32 games under .500, the second-worst record in franchise history (their .300 winning percentage was only 22 percentage points higher than the 1918–19 Arenas).

Many times, they made the playoffs with horrendous records. In 1987–88, for instance, they finished with the second-worst record in the league (and the third-worst record in franchise history, at .325), and only a point ahead of the Minnesota North Stars for the worst record. However, the Norris Division was so weak that year (only the Red Wings finished with a winning record) that the Leafs and Stars were actually still in playoff contention on the last day of the season. In those days, the four top teams in each division made the playoffs, regardless of record. The Leafs defeated the Red Wings in the final game of the regular season, while the Stars lost to the Flames. This handed the Leafs the final playoff spot from the division. Despite one of the worst winning percentages ever for a playoff team, the Leafs gave the Red Wings a surprisingly tough series in the first round, pushing them to six games. Many Leafs fans consider Ballard's tenure as owner to be the darkest era in team history; indeed, they only notched six winning seasons during Ballard's 18-plus years as majority owner, never finished above third in their division and only got out of the second round twice. The Leafs' subpar performance led some to call them the "Maple Laughs." The Leafs' poor record resulted in several high draft picks. Wendel Clark, the first overall pick in the 1985 draft went on to captain the team.

Resurgence in and after the 1990s

Ballard died in 1990. A year later, supermarket tycoon Steve Stavro, a longtime friend of Ballard's, bought the team from Ballard's estate in partnership with the Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan. Unlike Ballard, Stavro hated the limelight and rarely interfered in the Leafs' hockey operations.

After 1991–92, ex-Calgary Flames GM Cliff Fletcher took over the team. He made a series of trades and free agent acquisitions which turned the Leafs from an also-ran to a contender almost overnight. Unlike the league's other Canadian teams, the Leafs were not seriously impacted by the escalation of player salaries in the early 1990s. In fact, they actually thrived, as they were based in the league's fourth largest market.

The new stars paid almost immediate dividends in 1992–93. Doug Gilmour, who had come over from the Flames the previous season, scored 32 goals and 95 assists to lead the team in scoring. Dave Andreychuk had come to the Leafs from the Buffalo Sabres and would score 25 goals in his first 31 games as a Leaf as well as being the league's leading power-play goal scorer. Netminder Felix Potvin was also solid with an NHL-best 2.50 goals-against average. Toronto finished with a franchise-record 99 points, good enough for third place in the Norris Division and the eighth-best record in the league. The Leafs dispatched the Detroit Red Wings in the first round with an overtime winner from Nikolai Borschevsky in game seven, then won the Norris Division final by defeating the St. Louis Blues, also in seven games.

With Montreal facing the New York Islanders in the Wales Conference final, Canadians and hockey purists began dreaming of a Montreal-Toronto Cup final, as the Leafs faced the Los Angeles Kings, led by their captain Wayne Gretzky, in the Campbell Conference final. The Leafs were up 3–2 in the series, but lost game six. Gretzky's hat-trick in game seven would finish the Leafs' run, and it would be the Kings who would move on to the Finals against the Canadiens.

The Leafs had another strong season in 1993–94, finishing with 98 points. This was good enough for the fifth-best record in the league—their highest overall finish in 16 years. However, despite finishing one point above the Calgary Flames, the Leafs were seeded third in the Western Conference (formerly the Campbell Conference) by virtue of the Flames' Pacific Division title. However, a six-game series against the Blackhawks and a seven-game series against the San Jose Sharks took their toll on the team; they were defeated by the Vancouver Canucks—a team that finished 13 points below them in the regular season—in five games.

After two years out of the playoffs in the late 1990s, the Leafs made another charge during the 1999 playoffs after moving from Maple Leaf Gardens to the new Air Canada Centre. Mats Sundin, who had joined the team from the Quebec Nordiques in a 1994 trade involving Wendel Clark, had one of his most productive seasons, scoring 31 goals and totaling 83 points. Sergei Berezin scored 37 goals, Curtis Joseph won 35 games with a 2.56 GAA, and enforcer Tie Domi racked up 198 penalty minutes. The Leafs eliminated the Philadelphia Flyers and Pittsburgh Penguins in the first two rounds of the playoffs, but lost in five games to the Buffalo Sabres in the Eastern Conference Finals.

The Maple Leafs would reach the second round in both 2000 and 2001, losing both times to the New Jersey Devils, who would make the Stanley Cup Finals both seasons. The 2000 season was particularly notable because it marked the Leafs' first division title in 37 years, as well as the franchise's first-ever 100-point season. The season ended on a particular low, however, with the Leafs being held to just 6 shots in the final contest (game six) against the Devils.

In 2002, they would dispatch the Islanders and their trans-Ontario rivals, the Ottawa Senators, in the first two rounds, only to lose to the Cinderella-story Carolina Hurricanes in the Conference Finals. The 2002 season was particularly impressive in that the Leafs had many of their better players sidelined by injuries, but managed to make it to the conference finals due to the efforts of lesser-known players who were led mainly by Gary Roberts, who put up a heroic fight, although they would eventually fall to the Hurricanes.

Joseph left to go to the defending champion Red Wings in the 2002 off-season; the team almost immediately found a replacement in veteran Ed Belfour, who came over from the Dallas Stars and had been a crucial part of their 1999 Stanley Cup run. Belfour could not help their playoff woes in the 2003 playoffs, however, as they lost to Philadelphia in seven games in the first round. The 2003–04 season started in an uncommon way for the team, as they held their training camp in Sweden, and playing in the NHL Challenge against teams from Sweden and Finland. That year, the Leafs posted a franchise-record 103 points. They also finished with the fourth-best record in the league—their best overall finish in 41 years. They also managed a .628 win percentage, their best in 43 years (and the third-best in franchise history). They defeated the Senators in the first round of the playoffs for the fourth time in five years, but lost to the Flyers in the second round in six games. The Leafs did not make the playoffs in 2006, finishing tenth in the Eastern Conference. During the 2007-2008 season again the Leafs struggled in their division, only this time, their Captain, Mats Sundin was asked to waive his no-trade claus to try and advance the team's hopes of the playoffs, and a more promising 2008-2009 season.[13] Sundin declined, acknowledging that from his perspective the Leafs still had the chance to make the playoffs, and that he did not want to be a "rental player" to a playoff bound team. The other glaring factor, though rarely discussed was the obvious contractual obligation both parties had entered into when Sundin's contract was originally written - the no trade claus. It is widely speculated that culmination of these events soured Leaf fans and also strained relations between Sundin and the Toronto organization. Ultimately, Toronto did not make the playoffs during the 2007-2008 season, and Mats Sundin was an unrestricted free agent, contemplating retirement from the NHL.[14] Following approximately 9 months of contemplation, Mats Sundin returned to the NHL signing with the Vancouver Canucks.[15] Mats cited his decision to return to the NHL was based partly on "having a chance at winning the Stanley Cup".[16] Toronto faced Vancouver two times during the 2008-2009 season, losing in both showdowns, most notably during a shoot out decision on February 21, 2009 where Mats Sundin was honored at the ACC. He also scored the winning goal to defeat Toronto.[17]

The Toronto Maple Leafs are the only Original Six franchise to have neither won the Stanley Cup or a Conference title, since the 1967 NHL expansion.

See also

References

- Smythe, Thomas Stafford (2000). Centre Ice: the Smythe family, the Gardens and the Toronto Maple Leafs. Fenn Publishing.

- ↑ http://www.mapleleafs.com/history/1920s.asp

- 1 2 Hunter, Douglas (1997). Champions: The Illustrated History of Hockey's Greatest Dynasties. Chicago: Triumph Books. ISBN 1-57243-213-6.

- ↑ "The Toronto Maple Leaf Hockey Club, Limited" (advertisement), Toronto Star, February 17, 1927, p. 18.

- ↑ "Good-bye St. Pats, howdy Maple Leafs," The Globe, February 15, 1927, p. 6

- ↑ "Toronto crumbles New York chances," The Globe, February 18, 1927, p. 8.

- ↑ Lance Hornby "The Story of Maple Leaf Gardens, 100 Memories at Church and Carlton", p. 37.

- ↑ Hockey’s Book of Firsts, p.66, James Duplacey, JG Press, ISBN 978-1-57215-037-9

- ↑ [Smythe], pp. 44–45.

- ↑ McDonell, Chris. (2005). Hockey's Greatest Stars: Legends and Young Lions. Firefly Books. p. 84. ISBN 1-55407-038-4.

- ↑ [Smythe], p. 105.

- ↑ Hockey’s Book of Firsts, p.27, James Duplacey, JG Press, ISBN 978-1-57215-037-9

- 1 2 "Lanny McDonald trade has Sittler in tears," Jim Kernaghan, Toronto Star, December 29, 1979, p. 1.

- ↑ http://toronto.ctv.ca/servlet/an/local/CTVNews/20080225/sundin_future_080224/20080224?hub=TorontoHome

- ↑ Hunter, Paul (August 1, 2008). "Mats Sundin ponders retirement". The Star. Toronto. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ↑ http://www.theprovince.com/sports/hockey/canucks-hockey/Mats+Sundin+Vancouver+Canuck/1092523/story.html

- ↑ http://www.vancouversun.com/sports/wanted+chance+compete+Stanley+Sundin/1492918/story.html

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fxpNz_dM2fw