History of the University of Mannheim

The University of Mannheim has no clearly defined foundation date. While the University as it is known today was officially founded in 1967, its roots can be dated back to the 18th century established Theodoro Palatinae (Palatine Academy of the Sciences Mannheim) and the Handelshochschule (Commercial College Mannheim) that dates back to the beginning of the 20th century. Mannheim's history is closely tied to the history of its main campus – the Mannheim Baroque Palace.

Origins

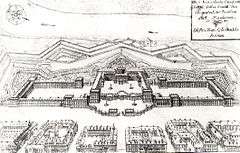

The Mannheim Palace itself dates back to the early 18th century. The city of Mannheim, founded in 1606, was fortified and at the present site of the Mannheim Palace a fortress called Friedrichsburg was located, sometimes serving as alternative residence for the Elector, one of the most important territorial princes of the Holy Roman Empire. When Elector Palatine Karl Philip III. had confessional controversies with the inhabitants of his capital city Heidelberg, he decided to appoint Mannheim the Palatinate's new capital in year 1720.

.jpg)

Charles Philip III. decided subsequently to construct a new palace as his residence on the site of the old "Friedrichsburg". In general, it was part of a trend among the German princes to construct grand new residences in that era.The construction of the palace was commenced solemnly on 2 June 1720. The overall building process was intended to cost about 300,000 Gulden, financed by an extraordinary "palace tax" (Schlossbausteuer), but in the end, the palace cost totalled more than 2,000,000 Gulden and severely worsened the Palatinate's financial situation. The first administrative institutions began using the Mannheim palace in 1725, but Karl Philip III. was able to transfer his court to the new residence only in 1731.

.jpg)

The final construction was not completed until 1760. Karl Philip died in 1742 and was succeeded by a distant relative, the young Count Palatine of Sulzbach and later Duke of Bavaria Charles Theodor. Under the initiative of the Alsacian scholar Johann Daniel Schöpflin and following the general academization movement in Europe, Prince Charles Theodor established the Palatine Academy of the Sciences Mannheim (Kurpfälzische Akademie der Wissenschaften) on October 17, 1763. The so-called Academia Electoralis Scientiarum et Elegantiorum Literarum Theodoro-Palatinae, shortened "Theodoro Palatinae" concentrated on the teaching of Natural Sciences and History, and soon earned itself a reputation which reached far beyond the borders of Charles Theodor's realm. In 1778, a second school was established at Mannheim's palace – the Commercial School (Großherzogliche Handelsschule) – that served as school for merchant sons and which was later named into "Grand-Ducal Commercial Academy".[1] Further associated institutions included the Mannheim Observatory, the Ducal Natural History Collection, the Ducal Physical Cabinet, the Mannheim Palace Botanical Garden and the in 1769 founded Mannheim Academy of Fine Arts. The establishment of the Theodoro-Palatinae had a strong cultural and educational policy link and intended to foster the sciences and arts in the Palatinate. Under Charles Theodor's reign the academy received enormous funding of more than 35,000,000 Gulden and contributed considerably to the cultural, economical and infrastructural development of Southern Germany during the second half of the eighteenth century. Charles Theodor developed Mannheim into a German centrum for Arts and Sciences.

Not only the palace, but also the city of Mannheim saw their zenith during Charles Philipp's reign. The glamour of the Elector's court and Mannheim's then famous cultural life lasted until 1778 when Charles Theodor became Elector of Bavaria by inheritance and moved his court to Munich. Things worsened further during the Napoleonic Wars, when Mannheim was besieged. During Napoleon's reorganization of Germany, the Electorate of the Palatinate was split up and Mannheim became part of the Grand Duchy of Electorate-Bavaria, thus losing its capital/residence status. Although Mannheim kept the title of "residence", the Mannheim Palace was used merely as accommodation for several administrative bodies. In addition, the reorganization of the Electorate of the Palatinate and Bavaria made the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities a major concurrent for academic funding. The consequences of religious strife, increased rivalry for funding and the Napoleonic Wars put an end to the "Theodoro-Palatinae", which was finally closed on February 17, 1803 after forty years of existence. Several years later in 1817, the "Grand-Ducal Commercial Academy" was closed as well.

20th century and nazi era

.jpg)

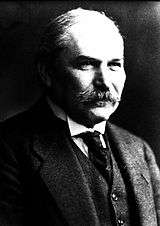

For most of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the palace served no uniform purpose, being used as a representative building and a museum for the city. Although there was no continuous existence of a scientific college in Mannheim, the newly established Handelshochschule Mannheim, or Municipal Commercial College Mannheim, founded in 1907, saw itself in the tradition of Carl Theodor's earlier colleges. The Handelshochschule was founded under an initiative from Mannheim's senior mayor Otto Beck (1846–1908) and the Heidelberg's economics professor Eberhard Gothein (1853–1923).

Although the Handelshochschule quickly developed into a well-known institution that conducted teaching and research in business administration, economics, pedagogy and psychology it suffered from financial hardship due to scarce financial resources. Since 1932 there had been plans to merge the Handelshochschule Mannheim with the Heidelberg University, hence both solving the School’s financial situation and supplementing the faculties at Heidelberg with business, psychology and pedagogy departments; nevertheless until 1933 no final decision regarding the integration of the Handelshochschule was made. This situation changed in mid-1933 when the social democratic municipal administration of Heidelberg and Mannheim was banished and replaced by a national socialistic one that pushed the merging process forward. In contrast to the initial plans featuring a full integration of the Handelshochschule, the national socialistic administration preferred a partial integration only that includes to supplement Heidelberg’s university with psychology and pedagogy institutes from the Handelshochschule Mannheim – in an aryanized outlay however.

Director of the Handelshochschule since 1929 was Otto Selz, a German philosopher and psychologist who is considered as being a pioneer of the cognitive sciences. As a result of the merger plans and especially due to his jewish background Selz was discharged on April 6, 1933 following the Badischen Judenerlass administered by NSDAP politician Robert Heinrich Wagner, a waiver designed to ban jewish academics from German universities. Later, Selz was deported to the concentration camp Auschwitz where he was executed in 1943; of the eleven docents at Mannheim's Handelshochschule that also possessed a jewish background nine shared Selz's fate.[2] The merger process became more concrete in June 1933 when Heidelberg’s Faculty for Philosophy and the University's Psychiatric Hospital discussed about the integration and allocation of Mannheim’s psychology department and concluded that while Heidelberg already has an academically strong psychiatric institution Mannheim’s departments would be a very valuable supplement. After several discussions and internal negotiations, both of Heidelberg University’s departments agreed on establishing a distinct Psychological Institute that fosters the clinical as well as the philosopical perspectives of psychology – hence, the Handelshochschule built the foundation of Heidelberg’s Institute for Psychology within the Heidelberg University Faculty of Behavioural Sciences and Empirical Cultural Sciences. In October 1933 Heidelberg university’s rectorate directed that students of the Handelshochschule Mannheim are allowed to continue their studies in Heidelberg and on October 25 a final meeting between Mannheim and ministries under Robert Heinrich Wagner was conducted to finalize the merger. The final contract included the transfer of all assets of the Handelshochschule to the Heidelberg University, the transfer of all existing institutes and collections to Heidelberg as well as the relocation of the Psychological Institute of the from then on former Handelshochschule Mannheim to the basement rooms of the Psychiatric Hospital department at the Heidelberg University. Only two weeks later the whole inventory and staff were transferred from Mannheim to Heidelberg – with this transfer the merging process was completed and the „jews released“ Handelshochschule Mannheim finally closed. While the institutes, collections and personnel had been transferred in 1933 the entire absorption process took until April 1938.[3]

Although the "Handelshochschule" was closed down in 1933, it built the foundation for what is today known as University of Mannheim.[4] In World War II, Mannheim was heavily bombed from December 1940 until the end of the war and saw more than 150 air raids. The largest raid on Mannheim took place on 5 and 6 September 1943 when a major part of the city was destroyed. In 1944, raids bombed and widely devastated the Mannheim Palace, leaving only one room undamaged out of over 500 – only its external walls survived. Many people supported demolishing it entirely after the war to create additional space for a more modern city architecture. These plans were abolished and the palace was reconstructed instead.

In 1946, the "Handelshochschule" re-opened under its new name Staatliche Wirtschaftshochschule Mannheim (State College for Economics) with a student body of 545 students in the school's first year. University of Mannheim's official seal has its origins during the time of the re-opening of the Handelshochschule. The official seal of the Trustees of the Staatliche "Wirtschaftshochschule" served as the signature and symbol of authenticity on documents issued by the corporation. A request for one was first recorded in a meeting of the trustees in 1946 during which some of the Trustees desired to get a Common Seal for the Use of the Corporation. The seal's design was chosen to represent the strong connection between Mannheim and the University of Mannheim and depicted the Mannheim Palace on top and the square-based outlay of Mannheim's downtown below; surrounded by In Omnibus Veritas, the University's official motto in a shortened version. UMA's motto was based on a line in the constitution from Carl Theodor's Palatine Academy of the Sciences Mannheim from 1763, In Omnibus Veritas Suprema Lex Esto that could be translated into "Truth in everything should be the supreme law". Ten years after its reopening, the "Staatliche Wirtschafshochschule" finally moved into the east wing of the meanwhile rebuilt palace. The other rooms of the old Residence were occupied by government officials whose offices were still in ruins after the war.[4]

In 1963, the "Staatliche Wirtschafshochschule Mannheim" extended its subject program faculties to a total of three – Business Administration and Social Sciences, Philosophy-Philological Sciences and Law – and subsequently gained the status as "university" on July, 4 in 1967.

Following the new status the council of ministers of the federal state of Baden-Württemberg decided to rename the State College into the "University of Mannheim" (Universität Mannheim). The University of Mannheim experienced continuous growth in both recognition and size. While there were only 3,150 students registered in 1967, the number of students tripled by the time of the mid-nineties counting more than 10,000 students.[5] In the winter term of 2013, the university's student body has reached its all-time high with more than 12,000 students. During the growth phase of the University in the 1960s and 1970s not only the number of students but also the number of faculties increased. In 1969, the University of Mannheim expanded its faculty number to eight by adding the faculties of Economics, Geography and Political Sciences and by splitting the faculties of Business Administration and Social Sciences as well as Philosophy-Philological Sciences.[6]

21st century

The emphasis at the University of Mannheim has always remained on business and economics, although teaching was broadened to further disciplines. In 2000, the university received as first German and third university in Europe the accreditation by Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business for its business administration faculty.[7] In the same year Mannheim initiated the Renaissance des Barockschlosses (Renaissance of the Mannheim Palace), a funding campaign aimed at raising funds for renovating and extending the main-campus. This aim was reached in the financial year 2006–2007, raising €53 million. In recent years, a policy referred to as "profile sharpening" (Profilschärfung) has been introduced to lift the University's reputation in its research clusters to a European level. The closing of majors such as geography (2002) and philosophy (2004) in the study program, due to this development back to the roots, has led to frequent complaints from the student council.[8] As one of the final steps in this transformation, the University of Mannheim has founded the Mannheim Business School (MBS) in 2005 to offer executive education in Germany. As a result of the transformation process the organizational structure was restructured and the number of faculties was decreased to six. Since 2007, the University of Mannheim is funded as the smallest university by the "Excellence Initiative" under an initiative started by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research and the German Research Foundation to promote cutting-edge research in Germany and subsequently established Germany's first graduate school, the Mannheim Graduate School for Economics and Social Sciences (GESS) in the same year. In 2008, the University passed a reformation statute to increase its cross-faculty collaboration and research and announced its profile as university with a strong focus on Economics, Business Administration, Social Sciences, Law, Mathematics, Computer Science and Humanities.

Notes and references

- ↑ Rauter Thomas Charles, The Eighteenth-Century "Deutsche Gesellschaft": A Literary Society of the German Middle Class. Ph.D. Thesis. Urbana, Illinois: Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1970. iv, 265 p.

- ↑ "Universität Mannheim – Zahlen und Geschichte". University of Mannheim. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ↑ "Universität Heidelberg – Institut für Psychologie: IV Während des Nationalsozialismus: Ein Institut entsteht". Heidelberg University. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- 1 2 Universität Mannheim – History. University of Mannheim.

- ↑ Facts about the University of Mannheim

- ↑ "Universität Mannheim – Romanisches Seminar - Institutsgeschichte". University of Mannheim. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ↑ "MANAGEMENT-TÜV FÜR MANNHEIM". UniSPIEGEL 2/2000. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ↑

Further reading

- Gaugler, Eduard. Die Universität Mannheim in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart, Mannheim, 1976. ISBN 978-3-874-55043-7

- Enzenauer, Markus. Wirtschaftsgeschichte in Mannheim, Mannheim, 2005. ISBN 978-3-938-03113-1

- AStA der Universität Mannheim. Was nicht im Rektoratsbericht stand: Wirtschaftshochschule, Universität Mannheim geheim: Annotationen zur Geschichte der Wirtschaftshochschule/Universität Mannheim im Kalten Krieg und danach, Universität Mannheim: Schriftenreihe des AStA der Universität Mannheim; Bd.

- Degner, Marius. Entwicklung von Professuren im Fach Betriebswirtschaftslehre, Universität Mannheim: Forschungsberichte / Universität Mannheim, Fakultät für Betriebswirtschaftslehre, Mannheim, 2009. ISSN 0340-1650

- Hamann, Horst. Universität Mannheim, Ed Panorama, Mannheim, 2007. ISBN 978-3-89823-330-9

- Grüb, Birgit. Gründung von Universitätsverlagen am Beispiel der Universität Mannheim, Mannheim Univ. Press, Mannheim, 2006. ISBN 978-3-939352-01-3

- Bauer, Gerhard; Budde, Kai; Kreutz, Wilhelm; Schäfer, Patrick. (Published for Academia Domitor - Studienforum Johann Jakob Hemmer e.V.): „Di fernunft siget“. Der kurpfälzische Universalgelehrte Johann Jakob Hemmer (1733-1790) und sein Werk (= Jahrbuch für internationale Germanistik. Reihe A, Kongressberichte, Band 103). Peter Lang, Bern 2010, p. 149–174. Online. ISBN 978-3-0343-0445-0

- Eid, Ludwig. Die gelehrten Gesellschaften der Pfalz, Verlag der Jägerschen Buchhandlung, Speyer, 1926.

- Ebersold, Guenther. Rokoko, Reform und Revolution. Ein politisches Lebensbild des Kurfürsten Karl Theodor. Frankfurt a. M. 1985. ISBN 978-3820454-86-4

- Fuchs, Peter. Kurfürst Karl Theodor von Pfalzbayern (1724−1799). In: Pfälzer Lebensbilder, Publisher. Kurt Baumann, Band 3, Speyer 1977, p. 65−105.

- Mörz, Stefan. Aufgeklärter Absolutismus in der Kurpfalz während der Mannheimer Regierungszeit des Kurfürsten Karl Theodor 1742−77. Stuttgart 1991. ISBN 978-3-1701118-68