Hop-Frog

| "Hop-Frog" | |

|---|---|

| Author | Edgar Allan Poe |

| Original title | "Hop-Frog; Or, the Eight Chained Ourangoutangs" |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) |

Horror Short story |

| Publisher | The Flag of Our Union |

| Media type | |

| Publication date | March 1849 |

"Hop-Frog" (originally "Hop-Frog; Or, the Eight Chained Ourangoutangs") is a short story by American writer Edgar Allan Poe, first published in 1849. The title character, a person with dwarfism taken from his homeland, becomes the jester of a king particularly fond of practical jokes. Taking revenge on the king and his cabinet for the king's striking his friend and fellow dwarf Trippetta, he dresses the king and his cabinet as orangutans for a masquerade. In front of the king's guests, Hop-Frog murders them all by setting their costumes on fire before escaping with Trippetta.

Critical analysis has suggested that Poe wrote the story as a form of literary revenge against a woman named Elizabeth F. Ellet and her circle.

Plot summary

The court jester Hop-Frog, "being also a dwarf and a cripple", is the much-abused "fool" of the unnamed king. This king has an insatiable sense of humor: "he seemed to live only for joking". Both Hop-Frog and his best friend, the dancer Trippetta (also small, but beautiful and well-proportioned), have been stolen from their homeland and essentially function as slaves. Because of his physical deformity, which prevents him from walking upright, the King nicknames him "Hop-Frog".

Hop-Frog reacts severely to alcohol, and though the king knows this, he forces Hop-Frog to consume several goblets full. Trippetta begs the king to stop, but instead the king, in front of seven members of his cabinet council, strikes her and throws another goblet of wine into her face, which makes Hop-Frog grit his teeth. The powerful men laugh at the expense of their two servants and ask Hop-Frog (who suddenly becomes sober and cheerful) for advice on an upcoming masquerade. He suggests some very realistic costumes for the men: costumes of orangutans chained together. The men love the idea of scaring their guests and agree to wear tight-fitting shirts and pants saturated with tar and covered with flax. In full costume, the men are then chained together and led into the "grand saloon" of masqueraders just after midnight.

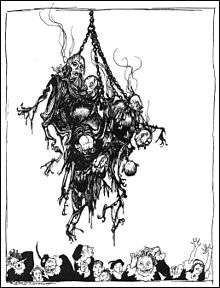

As predicted, the guests are shocked and many believe the men to be real "beasts of some kind in reality, if not precisely ourang-outangs". Many rush for the doors to escape, but the King had insisted the doors be locked; the keys are left with Hop-Frog. Amidst the chaos, Hop-Frog attaches a chain from the ceiling to the chain linked around the men in costume. The chain then pulls them up via pulley (presumably by Trippetta, who had arranged the room so) far above the crowd. Hop-Frog puts on a spectacle so that the guests presume "the whole matter as a well-contrived pleasantry". He claims he can identify the culprits by looking at them up close. He climbs up to their level, grits his teeth again, and holds a torch close to the men's faces. They quickly catch fire: "In less than half a minute the whole eight ourang-outangs were blazing fiercely, amid the shrieks of the multitude who gazed at them from below, horror-stricken, and without the power to render them the slightest assistance". Finally, before escaping through a sky-light with Trippetta to their home country, Hop-Frog identifies the men in costume:

I now see distinctly... what manner of people these maskers are. They are a great king and his seven privy-councillors—a king who does not scruple to strike a defenceless girl, and his seven councillors who abet him in the outrage. As for myself, I am simply Hop-Frog, the jester—and this is my last jest.

Analysis

The story, like "The Cask of Amontillado", is one of Poe's revenge tales, in which a murderer apparently escapes without punishment. In "The Cask of Amontillado", the victim wears motley; in "Hop-Frog", the murderer also dons such attire. However, while "The Cask of Amontillado" is told from the murderer's point of view, "Hop-Frog" is told from an unidentified third-person narrator's point of view.

The grating of Hop-Frog's teeth, right after Hop-Frog witnesses the king splash wine in Trippetta's face, and again just before Hop-Frog sets the eight men on fire, may well be symbolic. Poe often used teeth as a sign of mortality, as with the lips writhing about the teeth of the mesmerized man in "The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar" or the obsession with teeth in "Berenice".[1]

"The Cask of Amontillado" represents Poe's attempt at literary revenge on a personal enemy,[2] and "Hop-Frog" may have had a similar motivation. As Poe had been pursuing relationships with Sarah Helen Whitman and Nancy Richmond (whether romantic or platonic is uncertain), members of literary circles in New York City spread gossip and incited scandal about alleged improprieties. At the center of this gossip was a woman named Elizabeth F. Ellet, whose affections Poe had previously scorned. Ellet may be represented by the king himself, with his seven councilors representing Margaret Fuller, Hiram Fuller (no relation), Thomas Dunn English, Anne Lynch Botta, Anna Blackwell, Ermina Jane Locke, and Locke's husband.[3]

The tale is arguably autobiographical in other ways. The jester Hop-Frog, like Poe, is "kidnapped from home and presented to the king" (his wealthy foster father John Allan), "bearing a name not given in baptism but 'conferred upon him'" and is susceptible to wine ... when insulted and forced to drink becomes insane with rage".[4] Like Hop-Frog, Poe was bothered by those who urged him to drink, despite a single glass of wine making him drunk.[5]

Poe may have based the story on the Bal des Ardents at the court of Charles VI of France in January 1393. At the suggestion of a Norman squire, the king and five others dressed as Wild Men in highly flammable costumes made with pitch and flax.[5] Four of the men died in the fire, and only Charles and the fifth man were saved. Citing Barbara Tuchman as his source, Jack Morgan, of the University of Missouri–Rolla, author of The Biology of Horror, discusses the incident as a possible inspiration for "Hop-Frog".[6]

The king and his seven councilors appear in the masquerade at midnight, the same time that the Red Death appears in the masquerade in "The Masque of the Red Death", the narrator of "The Tell-Tale Heart" enters the old man's bedroom each night for one week, and the raven taps on the narrator's door in Poe's poem "The Raven".

Publication history

The tale first appeared in the March 17, 1849 edition of The Flag of Our Union, a Boston-based newspaper. It originally carried the full title "Hop Frog; Or, The Eight Chained Ourangoutangs". In a letter to friend Nancy Richmond, Poe wrote: "The 5 prose pages I finished yesterday are called — what do you think? — I am sure you will never guess — Hop-Frog! Only think of your Eddy writing a story with such a name as 'Hop-Frog'!"[7]

He explained that, though The Flag of Our Union was not a respectable journal "in a literary point of view", it paid very well.[7]

Adaptations

- French director Henri Desfontaines made the earliest film adaptation of "Hop-Frog" in 1910.

- James Ensor made a painting 1896, Kroller Muller Museum collection, and a print from 1898 etching, titled, Hop-Frog's Revenge, based on the story.

- A 1926 symphony by Eugene Cools was inspired by and named after Hop-Frog.

- A plot similar to "Hop-Frog" is used as a side plot in Roger Corman's The Masque of the Red Death (1964), starring Vincent Price as "Prince Prospero". Hop-Frog (called Hop-Toad in the film) is played by the actor Skip Martin, who was a "little person", but his dancing partner Esmeralda (analogous to Trippetta from the short story) is played by a child overdubbed with an older woman's voice.

- Elements of the tale are suggested in climax of the 1962 Universal/Hammer adaptation of The Phantom of the Opera (directed by Terence Fisher), the idea of a dwarf utilizing a chandelier as a murder weapon being particularly noteworthy.

- In 1992, Julie Taymor directed a short film entitled Fool's Fire adapted from "Hop-Frog". Michael J. Anderson of Twin Peaks fame starred as "Hop-Frog" and Mireille Mosse as "Trippetta", with Tom Hewitt as "The King". The film aired on PBS's American Playhouse and depicts all "normal" characters being dressed in masks and costumes (designed by Taymor) with only Hop-Frog and Trippetta shown as they truly are. Poe's poems "The Bells" and "A Dream Within A Dream" are also used as part of the story.

- A radio-drama production of "Hop-Frog" was broadcast in 1998 in the Radio Tales series on National Public Radio. The story was performed by Winifred Phillips and included music composed by her.

- The story features as part of Lou Reed's 2003 double album The Raven. One of the tracks is a song called "Hop-Frog" sung by David Bowie.

- Lance Tait's 2003 play Hop-Frog is based on this story. Laura Grace Pattillo wrote in The Edgar Allan Poe Review (2006), "a visually striking piece of theatrical storytelling, is Tait's adaptation of 'Hop-Frog'. In this play, the device of the Chorus functions exceptionally well, as one male and one female actor help narrate the story and speak for all of the supporting characters, who are represented by objects such as a long piece of wood and a collection of candles."[8]

References

- ↑ Kennedy, J. Gerald. Poe, Death, and the Life of Writing. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987. ISBN 0-300-03773-2 p. 79

- ↑ Rust, Richard D. "Punish with Impunity: Poe, Thomas Dunn English and 'The Cask of Amontillado'" in The Edgar Allan Poe Review, Vol. II, Issue 2 – Fall, 2001, St. Joseph's University.

- ↑ Benton, Richard P. "Friends and Enemies: Women in the Life of Edgar Allan Poe", in Myths and Reality: The Mysterious Mr. Poe. Baltimore: Edgar Allan Poe Society, 1987. p. 16

- ↑ Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. Harper Perennial, 1991. p. 407.

- 1 2 Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. p. 595. ISBN 0-8018-5730-9

- ↑ Morgan, Jack (2002). The Biology of Horror: Gothic Literature and Film. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0809324712.

- 1 2 Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. p. 594. ISBN 0-8018-5730-9

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/stable/41506252?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents