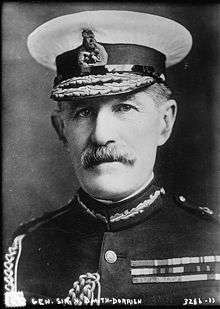

Horace Smith-Dorrien

| Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien | |

|---|---|

General Sir Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien | |

| Nickname(s) | "Smith Doreen", Smith D., S.D., Smithereens |

| Born |

26 May 1858 Haresfoot, Berkhamsted |

| Died |

12 August 1930 (aged 72) Chippenham, Wiltshire |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/branch | British Army |

| Years of service | 1876–1923 |

| Rank | General |

| Commands held |

Second Army II Corps Southern Command 19th Brigade |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath[1] Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Distinguished Service Order Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour (France)[2] |

| Other work | Governor of Gibraltar |

General Sir Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien, GCB, GCMG, DSO, ADC (26 May 1858 – 12 August 1930) was a senior British Army officer. One of the few British survivors of the Battle of Isandlwana as a young officer, he also distinguished himself in the Second Boer War.

Smith-Dorrien held senior commands in the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) during the First World War. He commanded II Corps at the Battle of Mons, the first major action fought by the BEF, and the Battle of Le Cateau, where he fought a vigorous and successful defensive action contrary to the wishes of the Commander-in-Chief Sir John French, with whom he had had a personality clash dating back some years. In the spring of 1915 he commanded the Second Army at the Second Battle of Ypres. He was relieved of command by French for requesting permission to retreat from the Ypres Salient to a more defensible position.

Early life and career

Horace Smith-Dorrien[3] was born at Haresfoot, a house near Berkhamsted, to Colonel Robert Algernon Smith-Dorrien and Mary Ann Drever. He was the twelfth child of sixteen; his eldest brother was Thomas Algernon Smith-Dorrien-Smith, the Lord Proprietor of the Isles of Scilly from 1872 – 1918.[4][5] He was educated at Harrow, and on 26 February 1876 entered the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. He had hoped to join the 95th Rifle Brigade of Peninsular War fame.[6] After passing out he was commissioned in 1877 as a subaltern to the 95th (Derbyshire) Regiment of Foot, later to become the Sherwood Foresters.[6][7]

Zulu War

On 1 November 1878, he was posted to South Africa where he worked as a transport officer. In this role he encountered, and fought against, corruption in the army.

Smith-Dorrien was present at the Battle of Isandlwana during the Zulu Wars on 22 January 1879, serving with the British invasion force as a transport officer for the army's Royal Artillery detachment. As Zulu forces overran the British forces, Smith-Dorrien narrowly escaped on his transport pony over 20 miles of rough terrain with twenty Zulu warriors in hot pursuit, crossing the Buffalo River, 80 yards wide and with a strong current, by holding the tail of a loose horse. Smith-Dorrien was one of fewer than fifty British survivors of the battle (many more native African troops on the British side also survived), and one of only five Imperial officers to escape the Zulu bloodbath.[8] Because of his conduct in trying to help other soldiers escape from the battlefield, including a colonial commisariat officer named Hamer whose life he saved, he was recommended for a Victoria Cross, but, as the recommendation did not go through the proper channels, he never received it. He took part in the rest of that war.[8]

His observations on the difficulty of opening ammunition boxes led to changes in British practice for the rest of the war, though modern commentators argue that this was not as important a factor in the defeat as was thought at the time.[6]

Egypt, India and Sudan

Smith-Dorrien served in Egypt under Evelyn Wood. He was promoted captain on 1 April 1882, appointed assistant chief of police in Alexandria on 22 August 1882, then given command of Mounted Infantry in Egypt on 3 September 1882, and was seconded to the Egyptian army (1 February 1884).[9] During this time, he forged a lifelong friendship with the then Major Kitchener. He met Gordon more than once, but his bad knee kept him off the expedition to relieve Khartoum. He served on the Suakin Expedition. On 30 December 1885, he witnessed the Battle of Gennis, where the British Army fought in red coats for the last time. The next day (31 December 1885) he was given his first independent command, 150 men (a mixture of hussars, mounted infantry and Egyptians) with fifty infantry in reserve. His task was to capture nine Arab river supply boats (nuggars), in order to achieve which he had to exceed his orders by going beyond the village of Surda, making a 60-mile journey on horseback in 24 hours. For this, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order in 1886.[9]

Smith-Dorrien then left active command to go to the Staff College, Camberley (1887–9). Staff College was not yet much respected, and he later recorded that he devoted much time to sport whilst there.[10]

He was posted to India, and promoted major on 1 May 1892. He became Deputy Assistant Adjutant-General, Bengal, on 1 April 1893 and then Assistant Adjutant General, Bengal, on 27 October 1894.[11][12] He returned to his regiment where he commanded troops during the Tirah Campaign of 1897–98.

In 1898, he transferred back to Egypt. He was promoted brevet lieutenant-colonel on 20 May 1898 and appointed Commanding Officer of the 13th Sudanese Battalion (16 July 1898).[11] He fought at the Battle of Omdurman (2 September 1898), where his infantry fired at Devishes from entrenched positions.[10] He commanded the British troops during the Fashoda incident. He was promoted brevet colonel 16 November 1898 and Commanding Officer of the Sherwood Foresters and substantive lieutenant-colonel (1 January 1899).[11]

South Africa

On 31 October 1899, he shipped to South Africa for the Second Boer War, arriving at Durban 13 December 1899, in the middle of “Black Week”.[10] On 2 February 1900, Lord Roberts put him in command of the 19th Brigade and, on 11 February, he was promoted to major general, making him one of youngest generals in the British Army at the time.[13] He later commanded a division in South Africa.[7]

He provided covering fire for French's Cavalry Division at Klipsdrift, and played an important role at the Battle of Paardeberg (18 to 27 February 1900), where he was summoned by Lord Roberts and asked for his views in the presence of Lord Kitchener, French and Henry Colville. He argued for the use of sapping and fire support, rather than attacking the entrenched enemy over open ground. Kitchener followed him to his horse to remonstrate that he would be "a made man" if he attacked as Kitchener wished, to which he replied he had given his views and would only attack if ordered to do so. A week later he took the laager after careful assault.[14]

At Sanna's Post (31 March 1900), Smith-Dorrien ignored inept orders from Colville to leave wounded largely unprotected and managed an orderly retreat without further casualties. He took part in the Battle of Leliefontein (7 November 1900). On 6 February 1901, Smith-Dorrien's troops were attacked in the Battle of Chrissiesmeer.

Smith-Dorrien's qualities as a commander meant he was one of a very few British commanders to enhance his reputation during this war. Smith-Dorrien was mentioned three times in the “London Gazette”, and Ian Hamilton later wrote highly of his performance and his grasp of the men's morale, whilst Roberts also thought highly of his South Africa performance.[14] He was at the top of a list (21 September 1901) of eighteen successful commanders of columns or groups of columns, including Haig and Allenby, whom French commended to Lord Roberts.[15]

India

On 22 April 1901, he received orders to return to India where he was made Adjutant-General (6 November 1901)[16] under Kitchener. He was placed in command of the 4th (Quetta) Division in Baluchistan, a post he held from 30 June 1903 until 1907. He was raised to Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath in 1904 and promoted lieutenant general on 9 April 1906. He introduced the Staff Ride, erroneously attributed by Terraine to Haig.[17] He also helped found the Staff College at Quetta in 1907.[10]

In the dispute between Kitchener and Lord Curzon over the role of the Military Member, Smith-Dorrien stayed neutral, torn between his relations with Kitchener and with the Military Member himself, Sir Arthur Power Palmer.

Home postings

Aldershot

Smith-Dorrien returned to England and, on 1 December 1907, became GOC of the Aldershot Command.[18] During this time, he instituted a number of reforms designed to improve the lot of the ordinary soldier. One was to abandon the practice of posting pickets to police the soldiers when they were outside the base. Another was to improve sports facilities. His reforms earned many plaudits (but were treated as an implied criticism by his predecessor, Sir John French).[19]

Unlike many senior generals of the era, Smith-Dorrien could speak to troops with ease and was greatly admired by regimental officers.[20] In prewar training he wanted “individual initiative and intelligence” in British soldiers.[21] He later wrote: “one could never become an up-to-date soldier in the prehistoric warfare to be met with against the Dervishes”.[22]

He improved the frequency and methods of training in marksmanship of all soldiers (including cavalry, and including shooting at moving targets).[19] During this period, the higher ranks of the army were divided on the best use of cavalry. Smith-Dorrien, along with Lord Roberts, Sir Ian Hamilton and others, doubted that cavalry could often be used as cavalry, i.e. that they should still be trained to charge with sword and lance, instead thinking they would be more often deployed as mounted infantry, i.e. using horses for mobility but dismounting to fight. To this end, he took steps to improve the marksmanship of the cavalry. This did not endear him to the arme blanche ('pro-cavalry') faction, which included French and Douglas Haig, and whose views prevailed after the retirement of Lord Roberts.

Aylmer Haldane recorded that at the 1909 manoeuvres French was “unfair” in summing up for Paget against Smith-Dorrien.[23] Smith-Dorrien annoyed French – with whom he had still been on relatively cordial terms at the end of the South African War – by abolishing the pickets which trawled the streets for drunk soldiers, by more than doubling the number of playing fields available to the men, by cutting down trees, and by building new and better barracks. On 21 August 1909 he lectured all his cavalry officers – in the 16th Lancers’ mess – about the importance of improving their men's musketry. By 1910 the feud between French and Smith-Dorrien was common knowledge throughout the Army. Smith-Dorrien, happily married to a young and pretty wife, objected to French’s womanising, and French’s nephew later claimed to have overheard “a ferocious exchange” between them, in which Smith-Dorrien declared “Too many whores around your headquarters, Field-Marshal”.[24]

He also tried to get the army to replace the old Maxim gun with the new Vickers Maxim gun, which weighed less than half as much and had a better water-cooling system, but the War Office did not approve the expenditure.[25]

In 1911, he was made Aide-de-Camp to King George V. He was part of the King's hunt in the Chitwan area of Nepal; on 19 December 1911, Smith-Dorrien killed a rhino and on the following day shot a bear.[26]

Southern Command

On 1 March 1912, he was appointed GOC Southern Command (Douglas Haig had succeeded him as GOC Aldershot).[27] At Southern Command he had jurisdiction over twelve counties and many regimental depots. He had experience of dealing with Territorials (who would make up much of II Corps in 1914) for the first time and instigated training on fire-and-movement withdrawals which would also prove useful at Le Cateau.[25]

He was promoted to full General (10 August 1912) and raised to Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in 1913.[11]

Although Smith-Dorrien was perfectly urbane and, by the standards of the day, kind-hearted towards his troops, he was notorious for furious outbursts of bad temper, which could last for hours before his equilibrium was restored. It has been suggested that the pain from a knee injury was one cause of his ill temper. It was rumoured that Smith-Dorrien’s temper was caused by some kind of serious illness. Esher (a royal courtier who exercised great influence over military appointments) had dined with Smith-Dorrien (28 January 1908) to see if he was indeed “changed and weakened”. Lord Crewe (letter to Seely 5 September 1913) turned him down for the post of Commander-in-Chief India because of his foul temper (A.J. Smithers, probably wrongly, blames French’s enmity for denying Smith-Dorrien the promotion[28]).[24][29]

Unlike French, he was politically astute enough to avoid becoming entangled in the Curragh Incident of 1914. Unlike a number of British generals of the era, Smith-Dorrien was not a political intriguer.[6]

First World War

In 1914, the Public Schools Officers' Training Corps annual camp was held at Tidworth Pennings, near Salisbury Plain. Lord Kitchener was to review the cadets, but the imminence of the war kept him elsewhere, and Smith-Dorrien was sent instead. He surprised the two-or-three thousand cadets by declaring (in the words of Donald Christopher Smith, a Bermudian cadet who was present) "that war should be avoided at almost any cost, that war would solve nothing, that the whole of Europe and more besides would be reduced to ruin, and that the loss of life would be so large that whole populations would be decimated. In our ignorance I, and many of us, felt almost ashamed of a British General who uttered such depressing and unpatriotic sentiments, but during the next four years, those of us who survived the holocaust – probably not more than one-quarter of us – learned how right the General's prognosis was and how courageous he had been to utter it."[30]

With the outbreak of the Great War, he was given command of the Home Defence Army, part of Ian Hamilton's Home Defence Central Force.[31] However, following the sudden death of Sir James Grierson, he was placed in charge of the British Expeditionary Force II Corps, by Lord Kitchener, the new Secretary of State for War. Field Marshal Sir John French had wanted Sir Herbert Plumer but Kitchener chose Smith-Dorrien as he knew he could stand up to French, and in the full knowledge that French disliked him.[32] Kitchener admitted to Smith-Dorrien that he had doubts about appointing him, but put them to one side.[31][33]

Smith-Dorrien arrived at GHQ (20 August) and formally asked French's permission to keep a special diary to report privately to the King as His Majesty had requested. French could hardly refuse, but this further worsened their relations.[34] Smith-Dorrien later claimed in his memoirs that French had received him “pleasantly”, but his diary at the time simply records matter-of-factly that he “motored into to Le Cateau and saw the Commander-in-Chief” which may be suspiciously brief in contrast to the diary's normally detailed description of other events. There was also personal friction between George Forestier-Walker and Johnnie Gough, the chiefs of staff of II Corps and I Corps respectively.[35]

Mons (23 August 1914)

French still believed (22 August) that there were only light German forces facing the BEF, but after hearing intelligence that German forces were stronger than thought and that the BEF had moved far ahead of Lanrezac's Fifth French Army on its right, Sir John cancelled the planned further advance. He told Lanrezac that he would hold his current position for another 24 hours.[36]

French's and Smith-Dorrien's accounts differ about the conference at 5.30am on 23 August. French's account in his memoirs “1914” stated that he had become doubtful of the advance into Belgium and warned his officers to be ready to attack or retreat. This agrees largely with French's diary at the time, in which he wrote that he had warned Smith-Dorrien that the Mons position might not be tenable. When “1914” was published, Smith-Dorrien claimed that French had been “in excellent form” at the meeting and had still been planning to advance. However, in his own memoirs Smith-Dorrien admitted that French had talked of either attacking or retreating, although he claimed that it had been he who had warned that the Mons position was untenable. Edmonds in the “Official History” agreed that French had probably been prepared either to attack or to retreat.[37] Edmonds – who was not an eyewitness – later claimed in his memoirs that French had instructed Smith-Dorrien to “give battle” on the line of the Conde Canal, and that when Smith-Dorrien queried whether he was to attack or defend he was simply told, after French had whispered with Murray, “Don’t ask questions, do as you are told”.[23][38]

Smith-Dorrien's II Corps took the brunt of a heavy assault by the German forces at Mons, with the Germans under von Kluck attempting a flanking manoeuvre. Forestier-Walker, Chief of Staff II Corps, was driven by Smith-Dorrien's foul temper to attempt to resign his post during the Battle of Mons but was told by the BEF Chief of Staff Murray “not to be an ass”.[39] During the battle of Mons Smith-Dorrien's car was almost struck by a German shell.[38]

Le Cateau (26 August)

French ordered a general retreat, during which I Corps (under General Douglas Haig) and II Corps became separated.[40] French agreed to Haig's retreat east of the Forest of Mormal (Haig Diary, 24 August) without, apparently, the knowledge of Smith-Dorrien. Murray noted in his diary (25 August) that GHQ had moved back from Le Cateau to St Quentin and that I Corps was being heavily engaged by night – making no mention of what II Corps were up to.[41] Because the German plan was to envelop the BEF from the west, most of the pressure fell on II Corps, which suffered higher casualties (2,000) in its fighting withdrawal on 24 August than at Mons the previous day (1,600).[42]

French had a long discussion with Murray and Wilson (25 August) as to whether the BEF should stand and fight at Le Cateau, a position which had been chosen for both I and II Corps to hold after they had retreated on either side of the Forest of Mormal. II Corps had been harried by German forces as it retreated west of the forest and Sir John wanted to fall back as agreed with Joffre, and hoped that the BEF could pull out of the fight altogether and refit behind the River Oise. Wilson issued orders to Smith-Dorrien to retreat from Le Cateau the next day.[40]

On the evening of 25 August Smith-Dorrien was unable to locate 4th Division and Cavalry Division. Allenby (GOC Cavalry Division) reached him at 2am on 26 August and reported that his horses and men were “pretty well played out” and unless they retreated under cover of darkness there would be no choice but to fight in the morning. Allenby agreed to act under Smith-Dorrien's orders. Hamilton (GOC 3rd Division) also reported that his men would be unable to get away before 9am, which also left little choice but to fight, lest isolated forces be overwhelmed in a piecemeal fashion.[43] A French cavalry corps under Sordet also took part on the west flank.[44]

French was awakened at 2am on 26 August with news that Haig's I Corps was under attack at Landrecies, and ordered Smith-Dorrien (3:50 am) to assist him. Smith-Dorrien replied that he was “unable to move a man”. This irritated French, as Haig (who already had serious doubts of French's competence) was a protegé of his.[45]

Smith-Dorrien finally managed to locate Snow (GOC of the newly arrived 4th Division), at 5am (his brigades were assembling in their positions between 3.30am and 5.30am) He was not under Smith-Dorrien's orders but agreed to assist.[43] Smith-Dorrien cancelled his orders to retreat and decided to stand and fight at Le Cateau. Smith-Dorrien still hoped for assistance from I Corps, which did not reach its intended position to the immediate east of Le Cateau. This news reached French at 5am – woken from his sleep once again, and insisting that the exhausted Murray not be woken, he telegraphed back that he still wanted Smith-Dorrien to “make every endeavour” to fall back but that he had “a free hand as to the method”, which Smith-Dorrien took as permission to make a stand. On waking properly, French ordered Wilson to telephone Smith-Dorrien and order him to break off as soon as possible. Wilson ended the conversation – by his own account – by saying “Good luck to you. Yours is the first cheerful voice I've heard in three days.”[45] Smith-Dorrien's slightly different recollection was that Wilson had warned him that he risked another Sedan.[46]

Von Kluck believed that he was facing the entire BEF (numbering, he believed, six divisions) and hoped to envelop it on both flanks, but lack of coordination among the German attackers ruled this out.[47]

After Le Cateau

Smith-Dorrien's decision to stand and fight enraged French, who accused him of jeopardising the whole BEF. French and his staff believed that II Corps had been destroyed at Le Cateau, although units reassembled after the retreat. Haig, despite believing French to be incompetent, wrote (4 Sep) of Smith-Dorrien's “ill-considered decision”. Murray later (in 1933) called Smith-Dorrien “a straight honourable gentleman, most lovable, kind and generous” but thought he “did wrong to fight other than a strong rearguard action”. However, Terraine praised the decision to stand and fight, arguing that despite heavy casualties, it halted the German advance.[48]

GHQ fell back to Noyon (26 August), and then and the next day Huguet and other French liaison officers gave Joffre a picture of shattered British forces falling back from Le Cateau. In fact Smith-Dorrien's staff were making intense efforts to hold II Corps together, although at a meeting (held at 2am on 27 August, as Smith-Dorrien had found GHQ's present location with great difficulty) French accused him of being overly optimistic.[49]

Smith-Dorrien (2 September) recorded that his men were much fitter and had recovered their spirits.[50] Smith-Dorrien's II Corps had the honour of leading the advance at the Marne and the First Battle of the Aisne, Haig's I Corps to his right being delayed by forests.[51]

First Battle of Ypres

The battle for Hill 60 was a notable struggle here. A defensive line at Neuve Chapelle became known as the Smith-Dorrien Trench (or, sometimes, the Smith-Dorrien Line).

II Corps was effectively broken up in late October to reinforce I Corps, but Smith-Dorrien was given Second Army (26 December 1914). His writings from the time show that he was fully aware of the importance of artillery, machine guns and aircraft.[52]

Second Battle of Ypres

Smith-Dorrien later recorded that French inflicted “pin-pricks” on him from February 1915 onwards, including the removal of Forestier-Walker as his Chief of Staff.[53] This was supposedly on the grounds that Forestier-Walker was needed to command a division training in England, although two months later he was still waiting to receive the command.[23] French told Haig that Smith-Dorrien was “a weak spot” (5 February 1915). During the Battle of Neuve Chapelle he was dissatisfied (13 March) at the “lack of determination” of Smith-Dorrien's diversionary attacks.[54] Smith-Dorrien was not always immune to the excessive optimism which British officers were expected to display throughout the war: Aylmer Haldane recorded in his diary (15 March 1915) that prior to the battle Smith-Dorrien had been claiming that the war would be won in March 1915.[55] However, French complained to Kitchener (Secretary of State for War) about him (28 March).[54]

At the Second Battle of Ypres, the British were defending a barely-tenable salient, held at great cost at the First Battle of Ypres five months earlier. On 22 April 1915, the Germans used poison gas on the Western Front for the first time and heavy casualties were sustained.

On 27 April, with the French counterattack (north of the salient) coming later and smaller than promised, Smith-Dorrien recommended withdrawal to the more defensible “GHQ Line”. Sir John privately agreed, but was angered that the suggestion came from Smith-Dorrien.[54] Sir John just wanted the situation kept quiet so as not to distract from the upcoming offensive at Aubers Ridge by Haig's First Army – one historian describes this attitude as “cretinous”.[56] Smith-Dorrien wrote a long letter (27 April) explaining the situation to Robertson (then chief of staff BEF). He received a curt telephone message telling him that, in Sir John's opinion, he had adequate troops to defend the salient. A few hours later written orders arrived, directing Smith-Dorrien to turn command of the salient over to Herbert Plumer[56] and to lend Plumer his chief of staff and such other staff officers as Plumer required. (In practice this meant that Plumer's V Corps, already holding the salient, became an autonomous force reporting directly to GHQ, with Smith-Dorrien left only with II Corps south of the salient). Plumer immediately asked permission for a withdrawal almost identical to that proposed by Smith-Dorrien. After a delay whilst Foch conducted another counterattack, French accepted.

On 30 April, Haig wrote in his diary

- Sir John also told me Smith-Dorrien had caused him much trouble. 'He was quite unfit [(he said)] to hold the Command of an Army' so Sir J. had withdrawn all troops from him control except the II Corps. Yet Smith-D. stayed on! [He would not resign!] French is to ask Lord Kitchener to find something to do at home. … He also alluded to Smith-Dorrien's conduct on the retreat, and said he ought to have tried him by Court Martial, because (on the day of Le Cateau) he 'had ordered him to retire at 8 am and he did not attempt to do so [but insisted on fighting in spite of his orders to retire]'.[57]

After French refused permission to retreat, Smith-Dorrien noted (6 May 1915) that the planned counterattack was a complete failure with casualties higher than predicted by GHQ.[58] Smith-Dorrien's eventual offer to resign (6 May) was ignored, and on that same day French used the 'pessimism' of the withdrawal recommendation as an excuse to sack him from command of Second Army altogether. "Wully" Robertson is said to have broken the news to him with the words " 'Orace, yer for 'ome " (Robertson was a former enlisted man who dropped his aitches), although by another account he might have said " 'Orace, yer thrown " (a cavalry metaphor).

The Official Historian Brigadier Edmonds later alleged that French had removed Smith-Dorrien as he was senior to Haig and stood in the way of Haig becoming Commander-in-Chief, and that Wilson had put the idea in French's mind, but this may be doubtful as their antipathy went back a long way and French was later (December 1915) replaced by Douglas Haig as Commander-in-Chief of the BEF against his will.[53]

Smith-Dorrien was raised to Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (14 May 1915) and was briefly appointed GOC First Home Army (22 June 1915).[11]

Remainder of the war

After a period in Britain, Smith-Dorrien was appointed GOC East Africa (22 November 1915) to fight the Germans in German East Africa (present day Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi) but pneumonia contracted during the voyage to South Africa prevented him from taking command. His former adversary, Jan Smuts, took on this command. Smith-Dorrien took no significant military part in the rest of the war. He returned to England in January 1916 and on 29 January 1917 was appointed lieutenant of the Tower of London.[11]

He led a campaign in London for moral purity, calling for suppression of "suggestive or indecent" media.[59]

French's memoirs

French, partly in response to criticism inspired by Smith-Dorrien, later wrote a partial and inaccurate account of the opening of the war in his book 1914, which attacked Smith-Dorrien. Smith-Dorrien, as a serving officer, was denied permission to reply in public.

French's official despatch after Le Cateau had praised Smith-Dorrien's “rare and unusual coolness, intrepididity and determination”. In 1914 French wrote that this had been written before he knew the full facts, and that Smith-Dorrien had risked destruction of his corps and lost 14,000 men and 80 guns (actual losses of each were around half of this number). Smith-Dorrien, in a private written statement, called 1914 “mostly a work of fiction and a foolish one too”.[60]

Final years

Smith-Dorrien's last position was as Governor of Gibraltar from 9 July 1918 – 26 May 1923, where he introduced an element of democracy and closed some brothels. According to Wyndham Childs in the summer of 1918, Smith-Dorrien tried, and nearly succeeded, in uniting the Comrades of the Great War, the National Association of Discharged Sailors and Soldiers, and the National Federation of Discharged and Demobilized Sailors and Soldiers into one body. The merger later took place in 1921 to form the British Legion.

He retired in September 1923, living in Portugal and then England. He devoted much his time to the welfare and remembrance of Great War soldiers. He worked on his memoirs, which were published in 1925. As French was still alive at the time of writing, he still felt unable to rebut 1914. Despite his treatment by French, in 1925, he rushed across Europe to act as a pallbearer at French's funeral,[61] an act appreciated by French's son.

He played himself in the film The Battle of Mons, released in 1926.[62][63]

In June 1925, he unveiled the war memorial in Memorial Avenue, Worksop.[64] On 4 August 1930, he unveiled the Pozières Memorial.

He died on 12 August 1930 following injuries sustained in a car accident in Chippenham, Wiltshire; he was 72 years old. He is buried in the Three Close Lane Cemetery of St Peter's Church, Berkhamsted.[65][66][67]

Family

On 3 September 1902 (on leave between being Adjutant General, India and taking command of 4th Division),[68] he married Olive Crofton Schneider at St Peter's, Eaton Square, London. She was the eldest daughter of Colonel John Henry Augustus Schneider and his wife, Mary Elizabeth (née Crofton) Schneider, of Oak Lea, Furness Abbey. Her brothers were Henry Crofton Schneider and Major Cyril Crofton Schneider. Olive's mother was the stepsister of Gen. Sir Arthur Power Palmer GCB, GCIE, who died in 1904.

The Smith-Dorriens had three sons:

- Grenfell Horace Gerald Smith-Dorrien[69] (born 1904) served in the army, reaching the rank of brigadier. He was killed by shellfire on 13 September 1944 during the Italian Campaign, whilst commanding the 169th (London) Infantry Brigade. His grave is in the Gradara War Cemetery, in the Commune of Gradara in the Province of Pesaro and Urbino.[70][71]

- Peter Lockwood Smith-Dorrien (born 1907) was killed in the King David Hotel bombing on 22 July 1946.[72]

- David Pelham Smith-Dorrien a.k.a. Bromley David Smith-Dorrien (29 October 1911 – 11 February 2001)[73][74] appears to have been an actor in the 1930s.[75] He joined the Foresters in 1940.[76] After the war, he worked to keep alive his father's reputation, designing a first-day cover commemorating the Battle of Le Cateau[77] and helping his father's biographer A. J. Smithers. He is buried in Kennington Cemetery.[78]

Horace and Olive Smith-Dorrien informally adopted Power Palmer's two daughters (Gabrielle and unknown), who were left homeless after his second wife's death in 1912. During the Great War Lady Smith-Dorrien founded the Lady Smith-Dorrien's Hospital Bag Fund. A problem had been identified that wounded soldiers often became separated from their personal effects while in hospital. Volunteers for the fund sewed between 40,000 and 60,000 bags a month to hold soldiers' valuables, totaling around five million throughout the war. For this work, she was created a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE). She also served as President of the animal welfare charity, The Blue Cross, alleviating the suffering of war horses.[79] For her services in that field, she received the gold medal of the Reconnaissance française.

In 1932, Olive Smith-Dorrien was named principal of the Royal School of Needlework (RSN). In 1937, the RSN worked on the Queen's Train (Coronation Robe), canopy and the two chairs to be used in Westminster Abbey during the Coronation.[80] She was awarded the King George VI Coronation Medal for work done. During the Second World War, she led the RSN in collecting lace which was sold for the war effort.[81] She revived the manufacture of hospital bags.[82] She died on 15 September 1951.[83][84][85]

Legacy

The following memorials have been established:

- Stall plate 14 in the Henry VII Chapel of Westminster Abbey (1913)[86]

- Dorrien, a vineyard area in South Australia (1916)[87]

- Mount Smith-Dorrien, Alberta, Canada (1918),[88] also naming the Smith-Dorrien Trail and Smith-Dorrien Creek, Alberta

- Smith-Dorrien Institute in Aldershot[65]

- Smith Dorrien Road, Leicester

- Smith Dorrien Avenue,[89] Smith Dorrien Bridge, and Smith Dorrien House, Gibraltar[65]

- Smith Dorrien Street, Netherby, South Australia

- Smith-Dorrien Avenue, Esterhazy, Saskatchewan

In 1931, after his death, the Smith-Dorrien Memorial was added to the Sherwood Foresters Memorial in Crich, Derbyshire, which Smith-Dorrien himself had opened on 6 August 1923.[65][90]

John Betjeman, mentions Horace in Chapter III "Highgate" of his autobiographical blank-verse poem Summoned by Bells:

In late September, in the conker time,

When Poperinghe and Zillebeke and Mons

Gratis with each half-pound of Brooke Bond tea.

Boomed with five-nines, large sepia gravures

Of French, Smith-Dorrien and Haig were given

Horace also features in the poem "Canada to England" by Craven Langstroth Betts:[91]

Lead out, lead out, Brave Mother, for the sake of sacked Louvain!

Give us our own Smith-Dorrien, yield us the van again!

Further reading

- Principal references

- Ballard, C, Smith-Dorrien, London: Constable and Co Ltd, 1931. — This is largely a condensed version of Smith-Dorrien's autobiography but for the first time included material from Smith-Dorrien's defence against French's allegations in 1914, now that both Smith-Dorrien and French had died.

- Beckett. Dr. Ian F, The Judgement of History: Lord French, Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien and 1914 Tom Donovan Publishing, 1993; ISBN 1-871085-15-2 — The bulk of this book is Smith-Dorrien's General Sir Horace Smith-Domien’s statement with regard to the first edition of Lord French’s book "1914”, his privately circulated rebuttal of French's criticisms of Smith-Dorrien's actions at Ypres. Useful introductory essay by Dr. Beckett.

- Beckett. Dr. Ian F, Corvi, Steven J. (editors) Haig's Generals Pen & Sword, 2006 ISBN 1-84415-169-7 — Includes a 25-page chapter by Steven Corvi with an emphasis on Smith-Dorrien's contributions to the Great War

- Fortescue, John William, Sir, 'Horace Smith-Dorrien' in Following the Drum Blackwood & Sons, Edinburgh, 1931, pp251–98.

- Smith-Dorrien, Sir Horace, General Sir Horace Smith-Domien’s statement with regard to the first edition of Lord French’s book "1914” c.1920

- Smith-Dorrien, Sir Horace, Memories of Forty-Eight Years' Service, John Murray, 1925. — Sir Horace's autobiography. (Republished as Smith-Dorrien: Isandlwhana to the Great War Leonaur, 2009 ISBN 978-1-84677-679-3)

- Smithers, A J, The Man Who Disobeyed: Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien and His Enemies, London: Leo Cooper, 1970 ISBN 0-85052-030-4 — Only modern biography.

- Theses

- Corvi, Steven J. General Sir Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien: Portrait of a Victorian Soldier in Modern War, unpublished PhD thesis, Northeastern University (Boston), 2002

- Siem, Richard Ray Forging the Rapier among Scythes: Lieutenant-General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien and the Aldershot Command 1907–1912, unpublished MA dissertation, Rice University (Houston), 1980. Now available online: Forging the rapier among scythes: Lieutenant-General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien and the Aldershot Command 1907–1912

- Archives relating to Smith-Dorrien

- "Archival material relating to Horace Smith-Dorrien". UK National Archives.

- DE LISLE, Gen Sir (Henry De) Beauvoir (1864–1955) (correspondence with Smith-Dorrien)

- SIMPSON-BAIKIE, Brig Gen Sir Hugh Archie Dundas (1871–1924) (manuscript letter to Simpson-Baikie from Gen Sir Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien on adverse comments about Smith-Dorrien in 1914 John French, 1st Viscount of Ypres, 1920 and typescript letter from Professor Robert Clifford Walton concerning Smith-Dorrien, 1972)

- Papers of Sir James Ramsay Montagu Butler (1889–1975) historian

- Other references

- Altham, E. A., Sir. The principles of war historically illustrated. With an introduction by General Sir Horace L. Smith-Dorrien 1914.

- Anon. Report on the 4th (Quetta) Division Staff Ride Under the Direction of Lieut.-General H.L. Smith-Dorrien C.B., D.S.O., Commanding 4th (Quetta) Division, May 1907 4th (Quetta) Divisional Press, 1907. (This was a five-day exercise conducted around Gulistan and north to Chaman on the North-West Frontier, involving an imaginary war with Russia.)

- Aston, Sir George Grey "Sir H. Smith-Dorrien and the Mons retreat: A review of Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien's Memories of Forty-Eight Years' Service." The Quarterly Review April 1925 pp 408–428

- Childs, Wyndham Episodes and reflections: being some records from the life of Major-General Sir Wyndham Childs, K.C.M.G., K.B.E., C.B., one time second lieut., 2nd Volunteer Battalion, the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry Cassell, 1930

- Barnett, Kennet Bruce Handbook on Military Sanitation for Regimental Officers ... With an introduction by Lt.-General Sir Horace L. Smith-Dorrien Forster Groom & Co. London, 1912

- Gilson, Capt. Charles J. L. History of the 1st Battalion Sherwood Foresters (Notts. and Derby Regt.) in the Boer War 1899–1902 Swan Sonnenschein & Co. Ltd. 1908. Introduction by Lieut.-Gen. Sir H L. Smith Dorrien. Reprinted by Naval & Military Press. Much of this introduction can be read in this PDF extract.

- Hastings, Max (2013). Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes To War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-59705-2.

- Holmes, Richard The Little Field Marshal: A Life of Sir John French Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004 ISBN 0-297-84614-0 — Includes a good account of French's relationship with Smith-Dorrien.

- Paice, Edward Tip and Run: The Untold Tragedy of the Great War in Africa Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2007, ISBN 978-0-297-84709-0 – Has some details of S-D's involvement with the East African campaign

- Neillands, Robin The Death of Glory: the Western Front 1915 (John Murray, London, 2006) ISBN 978-0-7195-6245-7

- [Pilcher, Major-General T. D.] A General's Letters to His Son on Obtaining His Commission Introduction by Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien. Cassell, 1917 (Author is uncredited in the book itself.) Reprinted 2009 by BiblioBazaar ISBN 978-1-103-99268-3 (Authorship of this book is incorrectly attributed by the publisher of the reprint to an "H. S. Smith-Dorrien")

- Robbins, Simon (2005). British Generalship on the Western Front. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-40778-8.

- Terraine, John (1960). Mons, The Retreat to Victory. Wordsworth Military Library, London. ISBN 1-84022-240-9.

- Travers, Tim (1987). The Killing Ground. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-85052-964-6.

- Who Was Who Vol. III (1929–1940) A & C Black Publishers Ltd Second Edition 1967 ISBN 978-0-7136-0170-1

- Winnifrith, Douglas Percy The Church in the Fighting Line: With General Smith-Dorrien at the Front, Being the Experiences of a Chaplain in charge of an Infantry Brigade London, Hodder and Stoughton, 1915 (Available online at: archive.org)

- Some books referring to Smith-Dorrien

- Live Search books referring to Smith-Dorrien

- Google Book Search books referring to Smith-Dorrien

References

- ↑ "Supplement to The London Gazette of FRIDAY, the 8th of November". London-gazette.co.uk. 8 November 1907. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ "Supplement to The London Gazette of Friday, 14 May, 1915". London-gazette.co.uk. 14 May 1915. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ Note: The surname is properly hyphenated though the form "Smith Dorrien" is sometimes seen. The first syllable of Dorrien is pronounced like the word "door".

- ↑ Burke's Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry, 18th edition, London 1965–1972, volume 1, page 87.

- ↑ Robert A Smith-Dorrien, Col. Herts Militia = Mary Ann, daughter of Dr Drever, by Mary A, daughter of Thos. Dorrien. By her he had (1) Thos. A, 10th Hussars; (2) Frances A L; (3) Frederick (1846–48), (5) Marian, (6) Henry T, (7) Walter M., (8) Amy, (9) Edith, (10) Alena P., (11) Arthur H, (12) Horace L, (13) Mary B., (14) Maud C, (15) Laura M., (16) Helen D. The Smith family, being a popular account of most branches of the name – however spelt – from the fourteenth century downwards, with numerous pedigrees now published for the first time

- 1 2 3 4 Beckett & Corvi 2006, p. 183.

- 1 2 Travers 1987, p. 291.

- 1 2 Beckett & Corvi 2006, p. 185.

- 1 2 Beckett & Corvi 2006, pp. 184, 185.

- 1 2 3 4 Beckett & Corvi 2006, p. 186.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Beckett & Corvi 2006, p. 184.

- ↑ The biographical summary given by Tim Travers does not appear to reconcile exactly with that presented by Ian Beckett. Travers has him as DAAG Punjab 1894-6, then DAAG Chitral 1895 (Travers 1987, p. 291).

- ↑ Beckett & Corvi 2006, pp. 184, 187.

- 1 2 Beckett & Corvi 2006, pp. 187–188.

- ↑ Holmes 2004, p114-5

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 27397. p. 297. 14 January 1902.

- ↑ Beckett & Corvi 2006, pp. 184, 188.

- ↑ "The London Gazette, 13 December 1907. 8689". London-gazette.co.uk. 13 December 1907. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- 1 2 Beckett & Corvi 2006, p. 189.

- ↑ Robbins 2005, p. 17.

- ↑ Travers 1987, p. 47.

- ↑ Robbins 2005, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 Travers 1987, pp. 15–16.

- 1 2 Holmes 2004, p131-3

- 1 2 Beckett & Corvi 2006, p. 190.

- ↑ Kees Rookmaaker, Barbara Nelson and Darrell Dorrington "The royal hunt of tiger and rhinoceros in the Nepalese terai in 1911" Pachyderm No. 38, January–June 2005 pp. 91–92.

- ↑ "The London Gazette, 5 March 1912, p1663". London-gazette.co.uk. 5 March 1912. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ Holmes 2004, p5

- ↑ Although Holmes does not specifically say so, this presumably refers to the appointment of Beauchamp Duff in March 1914. Crewe had not yet been Secretary of State for India in 1909 when O’Moore Creagh had succeeded Kitchener.

- ↑ Donald Christopher Smith, ed. John William Cox, Jr. Merely For the Record: The Memoirs of Donald Christopher Smith 1894–1980 (Bermuda, privately printed c. 1982), p. 59.

- 1 2 Beckett & Corvi 2006, p. 191.

- ↑ Holmes 2004, pp. 208–209.

- ↑ Terraine 1960, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Holmes 2004, p. 212.

- ↑ Beckett & Corvi 2006, p. 192.

- ↑ Holmes 2004, pp. 213–215.

- ↑ Holmes 2004, pp. 215–216.

- 1 2 Beckett & Corvi 2006, pp. 193–194.

- ↑ Holmes 2004, p. 224.

- 1 2 Holmes 2004, pp. 220–222.

- ↑ Beckett & Corvi 2006, p. 195.

- ↑ Terraine 1960, p. 112.

- 1 2 Terraine 1960, pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Beckett & Corvi 2006, p. 200.

- 1 2 Holmes 2004, pp. 222–223.

- ↑ Hastings 2013, p222

- ↑ Terraine 1960, p. 132.

- ↑ Holmes 2004, pp. 223–225.

- ↑ Holmes 2004, p. 226.

- ↑ Terraine 1960, p. 178.

- ↑ Terraine 1960, p. 197.

- ↑ Beckett & Corvi 2006, p. 201.

- 1 2 Beckett & Corvi 2006, p. 204.

- 1 2 3 Holmes 2004, pp. 272–274, 282–284.

- ↑ Robbins 2005, p. 70.

- 1 2 Neillands 2006, pp. 110–114.

- ↑ Sheffield, Gary and Bourne, John (editors) Douglas Haig: War Diaries and Letters 1914–1918 Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2005 ISBN 0-297-84702-3 pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Beckett & Corvi 2006, p. 203.

- ↑ Jerry White, Zeppelin Nights: London in the First World War, cited in review by Saul David in Evening Standard, 8 May 2014, page 41.

- ↑ Holmes 2004, p. 223.

- ↑ Neillands 2006, p. 116.

- ↑ Saturday, 22 August 2009 Michael Duffy (22 August 2009). "Vintage Video: Sir Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien, 1914". Firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ The Battle of Mons (WMV format, 14 seconds, 377KB).

- ↑ Published on 19/09/2011 10:13 (19 September 2011). "When the King came to town". Worksopguardian.co.uk. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Lt HL Smith-Dorrien, 95th Regt, Special Service Officer, veteran of the Anglo Zulu War of 1879

- ↑ Terry Jackson Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien 13 June 2010.

- ↑ "Remembering General Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien". Westernfrontassociation.com. 30 August 2010. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ Beckett & Corvi 2006, p. 188.

- ↑ Bassano portrait at Grenfell Horace Gerald Smith-Dorrien; Sir Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien

- ↑ Reading Room Manchester (13 September 1944). "Casualty Details: Smith-Dorrien, Grenfell Horace Gerald". Cwgc.org. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ "Grenfell Horace Gerald Smith-Dorrien". Findagrave.com. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ Peter Lockwood Smith-Dorrien 1907–1946

- ↑ "David Smith-Dorrien". Ftvdb.bfi.org.uk. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ "The London Gazette". London-gazette.co.uk. 8 February 2002. p. 1691. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ "Davis Smith-Dorrien". Us.imdb.com. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ "Supplement to the London Gazette" (PDF). 16 January 1940. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ "Dacorum Heritage Trust: General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien – The Hero of Le Cateau". Dacorumheritage.org.uk. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ "Bromley David Smith-Dorrien profile". Findagrave.com. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ Olive Smith-Dorrien For Horses of the Allies.; Lady Smith-Dorrien Makes an Appeal for the Blue Cross The New York Times 15 December 1915, p. 14.

- ↑ "Her Majesty'S Coronation Train". Britishpathe.com. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ History of the Royal School of Needlework

- ↑ "Lady Smith-Dorrien making cotton bags at the Royal School of Needlework, London". Jamd.com. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ The obituary of Lady Olive Smith-Dorrien

- ↑ "The London Gazette". London-gazette.co.uk. 23 November 1951. p. 6159. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ "Lady Olive Smith-Dorrien". Findagrave.com. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ "The Most Honourable Order of the Bath, its History, Ceremony, Coats of Arms and Crests". Heraldicsculptor.com. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ Seppeltsfield

- ↑ "Mount Smith-Dorrien". Peakfinder.com. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ In 1988, this was the scene of the killing of Seán Savage.

- ↑ "History of the Memorial". Crich-memorial.org.uk. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ Betts, Craven Langstroth The Perfume Holder and Other Poems J. T. White and company (1922), p. 245.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Horace Smith-Dorrien. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1922 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Horace Smith-Dorrien. |

- Obituary: General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien

- Sir Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien (1858–1930), General; Governor of Gibraltar: Sitter in 11 portraits (National Portrait Gallery)

- Olive Crofton (née Schneider), Lady Smith-Dorrien (National Portrait Gallery)

- Haresfoot, his birthplace, now a school

- 'The Story of a General' by Henry Newbolt (1916)

- General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien at South Lodge

- The London Gazette, 8 February 1901. p863 (Boer War)

- The London Gazette, 8 February 1901. p877

- Some Prominent British Generals and their Fortunes in The Great War – Smith-Dorrien

- A Book of Poems for the Blue Cross Fund (to help horses in war time) President, Lady Smith-Dorrien

- Smith-Dorrien, Horace Lockwood

- Horace Lockwood Smith Dorrien 1858–1930 (Family tree details)

- Horace Lockwood SMITH-DORRIEN, Queen Victoria's Last General

- War hero, soldier's friend, movie star, grumpy old man

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Beauchamp Duff |

Adjutant-General, India 1901–1903 |

Succeeded by Beauchamp Duff |

| Preceded by Sir John French |

GOC-in-C Aldershot Command 1907–1912 |

Succeeded by Sir Douglas Haig |

| Preceded by Sir Charles Douglas |

GOC-in-C Southern Command 1912–1914 |

Succeeded by Sir William Campbell |

| Preceded by James Grierson |

GOC II Corps August 1914 – December 1914 |

Succeeded by Charles Fergusson |

| Preceded by New Post |

Commander, British Second Army 1914–1915 |

Succeeded by Sir Herbert Plumer |

| Government offices | ||

| Preceded by Sir Herbert Miles |

Governor of Gibraltar 1918–1923 |

Succeeded by Sir Charles Monro |