Hydroxychloroquine

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Plaquenil, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601240 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth (tablets) |

| ATC code | P01BA02 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Variable (74% on average); Tmax = 2–4.5 hours |

| Protein binding | 45% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Biological half-life | 32–50 days |

| Excretion | Mostly Kidney (23–25% as unchanged drug), also biliary (<10%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

118-42-3 |

| PubChem (CID) | 3652 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 7198 |

| DrugBank |

DB01611 |

| ChemSpider |

3526 |

| UNII |

4QWG6N8QKH |

| KEGG |

D08050 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:5801 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL1535 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.864 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

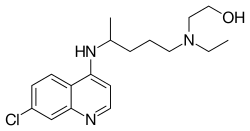

| Formula | C18H26ClN3O |

| Molar mass | 335.872 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| | |

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), sold under the trade names Plaquenil among others, is an antimalarial medication. It is also used to reduce inflammation in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (see disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs) and lupus. Hydroxychloroquine differs from chloroquine by the presence of a hydroxyl group at the end of the side chain: the N-ethyl substituent is beta-hydroxylated. It is available for administration by mouth as hydroxychloroquine sulfate.

It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, a list of the most important medication needed in a basic health system.[1]

Medical use

Hydroxychloroquine has been used for many years to treat malaria. It is also used to treat systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatic disorders like rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren's syndrome, and porphyria cutanea tarda. Its efficacy to treat Sjögren's syndrome has recently been called into question in a double-blind study involving 120 patients over a 48-week period.[2] Hydroxychloroquine increases[3] lysosomal pH in antigen-presenting cells. In inflammatory conditions, it blocks toll-like receptors on plasmacytoid dendritic cells (PDCs). Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR 9), which recognizes DNA-containing immune complexes, leads to the production of interferon and causes the dendritic cells to mature and present antigen to T cells. Hydroxychloroquine, by decreasing TLR signaling, reduces the activation of dendritic cells and the inflammatory process.

Hydroxychloroquine is also widely used in the treatment of post-Lyme arthritis following Lyme disease. It may have both an anti-spirochaete activity and an anti-inflammatory activity, similar to the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.[4]

Anti-diabetic activity of hydroxychloroquine has been demonstrated in a recently conducted systematic, randomized, active-controlled, multicentric study in type 2 diabetes patients uncontrolled on sulfonylurea and metformin combination. These patients were randomized to additionally receive either hydroxychloroquine or pioglitazone tablets. After 6 months of treatment, reduction in HbA1C and blood glucose was comparable between 2 treatment groups. Besides, patients treated with hydroxychloroquine showed a significant reduction in total cholesterol, triglycerides and LDL levels.[5]

Pharmacology

Pharmacokinetics

Hydroxychloroquine has similar pharmacokinetics to chloroquine, with rapid gastrointestinal absorption and elimination by the kidneys. Cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP2D6, 2C8, 3A4 and 3A5) metabolize hydroxychloroquine to N-desethylhydroxychloroquine.[6]

Pharmacodynamics

Antimalarials are lipophilic weak bases and easily go through plasma membranes. The free base form accumulates in lysosomes (acidic cytoplasmic vesicles) and is then protonated,[7] resulting in concentrations within lysosomes up to 1000 times higher than in culture media. This increases the pH of the lysosome from 4 to 6.[8] Alteration in pH causes inhibition of lysosomal acidic proteases causing a diminished proteolysis effect.[9] Higher pH within lysosomes causes decreased intracellular processing, glycosylation, and secretion of proteins with many immunologic and nonimmunologic consequences.[10] These effects are believed to be the cause of a decreased immune cell functioning such as chemotaxis, phagocytosis and superoxide production by neutrophils.[11] HCQ is a weak diprotic base that can pass through the lipid cell membrane and preferentially concentrate in acidic cytoplasmic vesicles. The higher pH of these vesicles in macrophages or other antigen-presenting cells limits the association of autoantigenic (any) peptides with class II MHC molecules in the compartment for peptide loading and/or the subsequent processing and transport of the peptide-MHC complex to the cell membrane.[12] Recently a novel mechanism has been described wherein hydroxychloroquine inhibits stimulation of the toll-like receptor (TLR) 9 family receptors. TLRs are cellular receptors for microbial products that induce inflammatory responses through activation of the innate immune system.[13]

As with other quinoline antimalarial drugs, the mechanism of action of quinine has not been fully resolved. The most accepted model is based on hydrochloroquinine, and involves the inhibition of hemozoin biocrystallization, which facilitates the aggregation of cytotoxic heme. Free cytotoxic heme accumulates in the parasites, causing their deaths.

Adverse effects

The most common adverse effects are a mild nausea and occasional stomach cramps with mild diarrhea. The most serious adverse effects affect the eye.

For short-term treatment of acute malaria, adverse effects can include abdominal cramps, diarrhea, heart problems, reduced appetite, headache, nausea and vomiting.

For prolonged treatment of lupus or arthritis, adverse effects include the acute symptoms, plus altered eye pigmentation, acne, anemia, bleaching of hair, blisters in mouth and eyes, blood disorders, convulsions, vision difficulties, diminished reflexes, emotional changes, excessive coloring of the skin, hearing loss, hives, itching, liver problems or liver failure, loss of hair, muscle paralysis, weakness or atrophy, nightmares, psoriasis, reading difficulties, tinnitus, skin inflammation and scaling, skin rash, vertigo and weight loss. Hydroxychloroquine can worsen existing cases of both psoriasis and porphyria.

Eyes

One of the most serious side effects is a toxicity in the eye (generally with chronic use).[14] People taking 400 mg of hydroxychloroquine or less per day generally have a negligible risk of macular toxicity, whereas the risk begins to go up when a person takes the medication over 5 years or has a cumulative dose of more than 1000 grams. The daily safe maximum dose for eye toxicity can be computed from one's height and weight using this calculator. Cumulative doses can also be calculated from this calculator. Macular toxicity is related to the total cumulative dose rather than the daily dose. Regular eye screening, even in the absence of visual symptoms, is recommended to begin when either of these risk factors occurs.[15]

Toxicity from hydroxychloroquine may be seen in two distinct areas of the eye: the cornea and the macula. The cornea may become affected (relatively commonly) by an innocuous cornea verticillata or vortex keratopathy and is characterized by whorl-like corneal epithelial deposits. These changes bear no relationship to dosage and are usually reversible on cessation of hydroxychloroquine.

The macular changes are potentially serious and are related to dosage and length of time taking hydroxychloroquine. Advanced retinopathy is characterized by reduction of visual acuity and a "bull's eye" macular lesion which is absent in early involvement.

Interactions

A type of enzyme deficiency (enzyme G6PD) found most frequently in those of African descent can develop into severe anemia and should also be monitored.[16] Children are more sensitive to hydroxychloroquine than are adults, and small doses can be potentially fatal.

The drug will transfer into breast milk and should be used with care by pregnant or nursing mothers.

Hydroxychloroquine generally does not have significant interactions with other medications but care should be taken if combined with medication altering liver function as well as aurothioglucose (Solganal), cimetidine (Tagamet) or digoxin (Lanoxin). HCQ can increase plasma concentrations of penicillamine which may contribute to the development of severe side effects. It also enhances hypoglycemic effects of insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents, so dose altering is recommended to prevent profound hypoglycemia. Antacids may decrease the absorption of HCQ. Both neostigmine and pyridostigmine antagonize the action of hydroxychloroquine.[17]

Overdose

Due to rapid absorption, symptoms of overdose can occur within a half an hour after ingestion. Overdose symptoms include convulsions, drowsiness, headache, heart problems or heart failure, difficulty breathing and vision problems.

Names

Brand names include Plaquenil, Axemal (in India), Dolquine and Quensyl.

References

- ↑ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ Effects of Hydroxychloroquine on Symptomatic Improvement in Primary Sjögren Syndrome, Gottenberg, et al. (2014) http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleID=1887760

- ↑ Waller; et al. Medical Pharmacology and Therapeutics (2nd ed.). p. 370.

- ↑ AC, Steere; SM, Angelis (October 2006). "Therapy for Lyme Arthritis: Strategies for the Treatment of Antibiotic-refractory Arthritis". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 54 (10): 3079–86. doi:10.1002/art.22131. PMID 17009226.

- ↑ Pareek, A; Chandurkar, N; Thomas, N; Viswanathan, V; Deshpande, A; Gupta, OP; Shah, A; Kakrani, A; Bhandari, S; Thulasidharan, NK; Saboo, B; Devaramani, S; Vijaykumar, NB; Sharma, S; Agrawal, N; Mahesh, M; Kothari, K (July 2014). "Efficacy and Safety of Hydroxychloroquine in the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: a Double Blind, Randomized Comparison with Pioglitazone". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 30 (7): 1257–66. doi:10.1185/03007995.2014.909393. PMID 24669876.

- ↑ Kalia, S; Dutz, JP (2007). "New Concepts in Antimalarial Use and Mode of Action in Dermatology". Dermatologic Therapy. 20 (4): 160–74. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2007.00131.x. PMID 17970883.

- ↑ Kaufmann, AM; Krise, JP (2007). "Lysosomal Sequestration of Amine-containing Drugs: Analysis and Therapeutic Implications". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 96 (4): 729–46. doi:10.1002/jps.20792. PMID 17117426.

- ↑ Ohkuma, S; Poole, B (1978). "Fluorescence Probe Measurement of the Intralysosomal pH in Living Cells and the Perturbation of pH by Various Agents". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 75 (7): 3327–31. doi:10.1073/pnas.75.7.3327. PMC 392768

. PMID 28524.

. PMID 28524. - ↑ Ohkuma, S; Chudzik, J; Poole, B (1986). "The Effects of Basic Substances and Acidic Ionophores on the Digestion of Exogenous and Endogenous Proteins in Mouse Peritoneal Macrophages". The Journal of Cell Biology. 102 (3): 959–66. doi:10.1083/jcb.102.3.959. PMC 2114118

. PMID 3949884.

. PMID 3949884. - ↑ Oda, K; Koriyama, Y; Yamada, E; Ikehara, Y (1986). "Effects of Weakly Basic Amines on Proteolytic Processing and Terminal Glycosylation of Secretory Proteins in Cultured Rat Hepatocytes". The Biochemical Journal. 240 (3): 739–45. doi:10.1042/bj2400739. PMC 1147481

. PMID 3493770.

. PMID 3493770. - ↑ Hurst, NP; French, JK; Gorjatschko, L; Betts, WH (1988). "Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine Inhibit Multiple Sites in Metabolic Pathways Leading to Neutrophil Superoxide Release". The Journal of Rheumatology. 15 (1): 23–7. PMID 2832600.

- ↑ Fox, R (1996). "Anti-malarial Drugs: Possible Mechanisms of Action in Autoimmune Disease and Prospects for Drug Development". Lupus. Jun;5 Suppl 1:S4-10.: S4–10. doi:10.1177/096120339600500103. PMID 8803903.

- ↑ Takeda, K; Kaisho, T; Akira, S (2003). "Toll-Like Receptors". Annual Review of Immunology. 21: 335–76. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. PMID 12524386.

- ↑ Flach, AJ (2007). "Improving the Risk-benefit Relationship and Informed Consent for Patients Treated with Hydroxychloroquine". Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 105: 191–4; discussion 195–7. PMC 2258132

. PMID 18427609.

. PMID 18427609. - ↑ Marmor, MF; Kellner, U; Lai, TYY; Lyons, JS; Mieler, WF (February 2011). "Revised Recommendations on Screening for Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine Retinopathy". Ophthalmology. 118 (2): 415–22. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.11.017. PMID 21292109.

- ↑ "Hydroxychloroquine (Oral Route) - MayoClinic.com". Retrieved 2008-10-30.

- ↑ "Russian Register of Medicines: Plaquenil (hydroxychloroquine) Film-coated Tablets for Oral Use. Prescribing Information" (in Russian). Sanofi-Synthelabo. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

External links

- HealthCentral Medication Information on Hydroxychloroquine

- Medicinenet Article on Hydroxychloroquine