Paraboloid

In mathematics, a paraboloid is a quadric surface of special kind. There are two kinds of paraboloids: elliptic and hyperbolic.

The elliptic paraboloid is shaped like an oval cup and can have a maximum or minimum point. In a suitable coordinate system with three axes x, y, and z, it can be represented by the equation[1]

where a and b are constants that dictate the level of curvature in the xz and yz planes respectively. This is an elliptic paraboloid which opens upward for c > 0 and downward for c < 0.

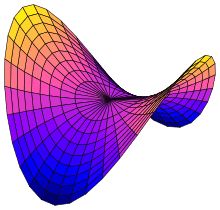

The hyperbolic paraboloid (not to be confused with a hyperboloid) is a doubly ruled surface shaped like a saddle. In a suitable coordinate system, a hyperbolic paraboloid can be represented by the equation[2]

For c > 0, this is a hyperbolic paraboloid that opens down along the x-axis and up along the y-axis (i.e., the parabola in the plane x = 0 opens upward and the parabola in the plane y=0 opens downward).

Properties

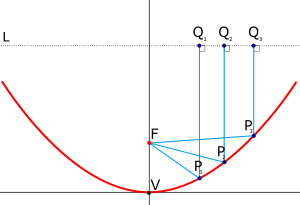

With a = b an elliptic paraboloid is a paraboloid of revolution: a surface obtained by revolving a parabola around its axis. It is the shape of the parabolic reflectors used in mirrors, antenna dishes, and the like; and is also the shape of the surface of a rotating liquid, a principle used in liquid mirror telescopes and in making solid telescope mirrors (see rotating furnace). This shape is also called a circular paraboloid.

There is a point called the focus (or focal point) on the axis of a circular paraboloid such that, if the paraboloid is a mirror, light from a point source at the focus is reflected into a parallel beam, parallel to the axis of the paraboloid. This also works the other way around: a parallel beam of light incident on the paraboloid parallel to its axis is concentrated at the focal point. This applies also for other waves, hence parabolic antennas. For a geometrical proof, click here.

The hyperbolic paraboloid is a doubly ruled surface: it contains two families of mutually skew lines. The lines in each family are parallel to a common plane, but not to each other.

Curvature

The elliptic paraboloid, parametrized simply as

and mean curvature

which are both always positive, have their maximum at the origin, become smaller as a point on the surface moves further away from the origin, and tend asymptotically to zero as the said point moves infinitely away from the origin.

The hyperbolic paraboloid, when parametrized as

has Gaussian curvature

and mean curvature

Geometric representation of multiplication table

If the hyperbolic paraboloid

is rotated by an angle of π/4 in the +z direction (according to the right hand rule), the result is the surface

and if a = b then this simplifies to

- .

Finally, letting a = √2, we see that the hyperbolic paraboloid

is congruent to the surface

which can be thought of as the geometric representation (a three-dimensional nomograph, as it were) of a multiplication table.

The two paraboloidal ℝ2 → ℝ functions

and

are harmonic conjugates, and together form the analytic function

which is the analytic continuation of the ℝ → ℝ parabolic function f(x) = x2/2.

Dimensions of a paraboloidal dish

The dimensions of a symmetrical paraboloidal dish are related by the equation

where F is the focal length, D is the depth of the dish (measured along the axis of symmetry from the vertex to the plane of the rim), and R is the radius of the rim. Of course, they must all be in the same units. If two of these three quantities are known, this equation can be used to calculate the third.

A more complex calculation is needed to find the diameter of the dish measured along its surface. This is sometimes called the "linear diameter", and equals the diameter of a flat, circular sheet of material, usually metal, which is the right size to be cut and bent to make the dish. Two intermediate results are useful in the calculation: P = 2F (or the equivalent: P = R2/2D) and Q = √P2 + R2, where F, D, and R are defined as above. The diameter of the dish, measured along the surface, is then given by

where ln x means the natural logarithm of x, i.e. its logarithm to base e.

The volume of the dish, the amount of liquid it could hold if the rim were horizontal and the vertex at the bottom (e.g. the capacity of a paraboloidal wok), is given by

where the symbols are defined as above. This can be compared with the formulae for the volumes of a cylinder (πR2D), a hemisphere (2π/3R2D, where D = R), and a cone (π/3R2D). Of course, πR2 is the aperture area of the dish, the area enclosed by the rim, which is proportional to the amount of sunlight a reflector dish can intercept. The surface area of a parabolic dish can be found using the area formula for a surface of revolution which gives

Applications

Paraboloidal mirrors are frequently used to bring parallel light to a point focus, e.g. in astronomical telescopes, or to collimate light that has originated from a source at the focus into a parallel beam, e.g. in a searchlight.

The top surface of a fluid in an open-topped rotating container will form a paraboloid. This property can be used to make a liquid mirror telescope with a rotating pool of a reflective liquid, such as mercury, for the primary mirror. The same technique is used to make solid paraboloids, in rotating furnaces.

The widely sold fried snack food Pringles potato crisps resemble a truncated hyperbolic paraboloid.[3] The distinctive shape of these crisps allows them to be stacked in sturdy tubular containers, fulfilling a design goal that they break less easily than other types of crisp.[4]

Examples in architecture

- Commonwealth Institute, in Kensington, London

- St. Mary's Cathedral, Tokyo

- Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Assumption, San Francisco, California

- Saddledome in Calgary, Alberta, Canada

- London Velopark

- Wrexham Swimming Baths, Wales

See also

- Ellipsoid

- Holophones

- Hyperboloid

- Hyperboloid structure

- Liquid mirror telescope, paraboloids produced by rotation

- Parabola

- Parabolic reflector

- Parabolic reflector#Focus-balanced reflector, paraboloid with focus at centre of mass

- Quadratic form

- Rotation of axes

- Saddle point

- Saddle roof

- Translation of axes

References

- ↑ Thomas, George B.; Maurice D. Weir; Joel Hass; Frank R. Giordiano (2005). Thomas' Calculus 11th ed. Pearson Education, Inc. p. 892. ISBN 0-321-18558-7.

- ↑ Thomas, George B.; Maurice D. Weir; Joel Hass; Frank R. Giordiano (2005). Thomas' Calculus 11th ed. Pearson Education, Inc. p. 896. ISBN 0-321-18558-7.

- ↑ Zill, Dennis G.; Wright, Warren S. (2011), Calculus: Early Transcendentals, Jones & Bartlett Publishers, p. 649, ISBN 9781449644482.

- ↑ Wyman, Carolyn (2004), "Pringles potato chips: A new use for tennis ball cans", Better Than Homemade: Amazing Foods that Changed the Way We Eat, Quirk Books, pp. 47–49, ISBN 9781931686426.