Hyperboloid model

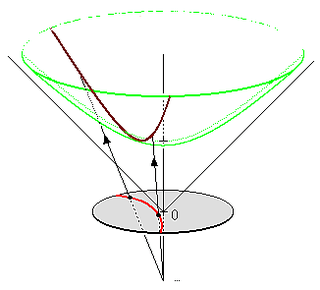

In geometry, the hyperboloid model, also known as the Minkowski model or the Lorentz model (after Hermann Minkowski and Hendrik Lorentz), is a model of n-dimensional hyperbolic geometry in which points are represented by the points on the forward sheet S+ of a two-sheeted hyperboloid in (n+1)-dimensional Minkowski space and m-planes are represented by the intersections of the (m+1)-planes in Minkowski space with S+. The hyperbolic distance function admits a simple expression in this model. The hyperboloid model of the n-dimensional hyperbolic space is closely related to the Beltrami–Klein model and to the Poincaré disk model as they are projective models in the sense that the isometry group is a subgroup of the projective group.

Minkowski quadratic form

If (x0, x1, …, xn) is a vector in the (n + 1)-dimensional coordinate space Rn+1, the Minkowski quadratic form is defined to be

The vectors v ∈ Rn+1 such that Q(v) = 1 form an n-dimensional hyperboloid S consisting of two connected components, or sheets: the forward, or future, sheet S+, where x0>0 and the backward, or past, sheet S−, where x0<0. The points of the n-dimensional hyperboloid model are the points on the forward sheet S+.

The Minkowski bilinear form B is the polarization of the Minkowski quadratic form Q,

Explicitly,

The hyperbolic distance between two points u and v of S+ is given by the formula

where arcosh is the inverse function of hyperbolic cosine.

Straight lines

A straight line in hyperbolic n-space is modeled by a geodesic on the hyperboloid. A geodesic on the hyperboloid is the (non-empty) intersection of the hyperboloid with a two-dimensional linear subspace (including the origin) of the n+1-dimensional Minkowski space. If we take u and v to be basis vectors of that linear subspace with

and use w as a real parameter for points on the geodesic, then

will be a point on the geodesic.[1]

More generally, a k-dimensional "flat" in the hyperbolic n-space will be modeled by the (non-empty) intersection of the hyperboloid with a k+1-dimensional linear subspace (including the origin) of the Minkowski space.

Isometries

The indefinite orthogonal group O(1,n), also called the (n+1)-dimensional Lorentz group, is the Lie group of real (n+1)×(n+1) matrices which preserve the Minkowski bilinear form. In a different language, it is the group of linear isometries of the Minkowski space. In particular, this group preserves the hyperboloid S. Recall that indefinite orthogonal groups have four connected components, corresponding to reversing or preserving the orientation on each subspace (here 1-dimensional and n-dimensional), and form a Klein four-group. The subgroup of O(1,n) that preserves the sign of the first coordinate is the orthochronous Lorentz group, denoted O+(1,n), and has two components, corresponding to preserving or reversing the spatial dimension. Its subgroup SO+(1,n) consisting of matrices with determinant one is a connected Lie group of dimension n(n+1)/2 which acts on S+ by linear automorphisms and preserves the hyperbolic distance. This action is transitive and the stabilizer of the vector (1,0,…,0) consists of the matrices of the form

Where belongs to the compact special orthogonal group SO(n) (generalizing the rotation group SO(3) for n = 3). It follows that the n-dimensional hyperbolic space can be exhibited as the homogeneous space and a Riemannian symmetric space of rank 1,

The group SO+(1,n) is the full group of orientation-preserving isometries of the n-dimensional hyperbolic space.

History

In 1880 Wilhelm Killing [2] used the representation he attributed to Karl Weierstrass for Lobachevskian geometry. Following Killing’s later (1885) attribution, the phrase Weierstrass coordinates has been associated with elements of the hyperboloid model as follows: given an inner product on , the Weierstrass coordinates of are

which can be compared to

for the hemisphere model.[3]

According to Jeremy Gray (1986),[4] Poincaré used the hyperboloid model in his personal notes in 1880. Gray shows where the hyperboloid model is implicit in later writing by Poincaré.[5]

Wilhelm Killing also described the hyperboloid model in 1885 in his Analytic treatment of non-Euclidean spaceforms.[6] Further exposure of the model was given by Alfred Clebsch and Ferdinand Lindemann in 1891 in Vorlesungen ŭber Geometrie, page 524.

The hyperboloid was explored as a metric space by Alexander Macfarlane in his Papers in Space Analysis (1894). He noted that points on the hyperboloid could be written as

where α is a basis vector orthogonal to the hyperboloid axis. For example, he obtained the hyperbolic law of cosines through use of his Algebra of Physics.[1]

H. Jansen made the hyperboloid model the explicit focus of his 1909 paper "Representation of hyperbolic geometry on a two sheeted hyperboloid".[7] In 1993 W.F. Reynolds recounted some of the early history of the model in his article in the American Mathematical Monthly.[8]

Being a commonplace model by the twentieth century, it was identified with the Geschwindigkeitsvectoren (velocity vectors) by Hermann Minkowski in his Minkowski space of 1908. Scott Walter, in his 1999 paper "The Non-Euclidean Style of Special Relativity" recalls Minkowski’s awareness, but traces the lineage of the model to Hermann Helmholtz rather than Weierstrass and Killing.

In the early years of relativity the hyperboloid model was used by Vladimir Varićak to explain the physics of velocity. In his speech to the German mathematical union in 1912 he referred to Weierstrass coordinates.

See also

Notes and references

- 1 2 Alexander Macfarlane (1894) Papers on Space Analysis, B. Westerman, New York, weblink from archive.org

- ↑ "Die Rechnung in Nicht-Euklidischen Raumformen" Crelle's Journal vol.89:265–87

- ↑ Elena Deza and Michel Deza (2006) Dictionary of Distances

- ↑ Linear differential equations and group theory from Riemann to Poincaré (pages 271,2)

- ↑ See also Poincaré: On the fundamental hypotheses of geometry 1887 Collected works vol.11, 71-91 and referred to in the book of B.A. Rosenfeld A History of Non-Euclidean Geometry p.266 in English version (Springer 1988).

- ↑ Die nicht-Euklidischen Raumformen in analytischer Behandlung (German) Teubner 1885 Leipzig

- ↑ Abbildung hyperbolische Geometrie auf ein zweischaliges Hyperboloid Mitt. Math. Gesellsch Hamburg 4:409–440.

- ↑ Reynolds, William F. (1993) "Hyperbolic geometry on a hyperboloid", American Mathematical Monthly 100:442–55, URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2324297

- Alekseevskij, D.V.; Vinberg, E.B.; Solodovnikov, A.S. (1993), Geometry of Spaces of Constant Curvature, Encyclopaedia of Mathematical Sciences, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-52000-7

- Anderson, James (2005), Hyperbolic Geometry, Springer Undergraduate Mathematics Series (2nd ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-1-85233-934-0

- Ratcliffe, John G. (1994), Foundations of hyperbolic manifolds, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-94348-0, Chapter 3

- Miles Reid & Balázs Szendröi (2005) Geometry and Topology, Figure 3.10, p 45, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-61325-6, MR 2194744.

- Ryan, Patrick J. (1986), Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometry: An analytical approach, Cambridge, London, New York, New Rochelle, Melbourne, Sydney: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-25654-2

- Varićak, V. (1912), "On the Non-Euclidean Interpretation of the Theory of Relativity", Jahresbericht der Deutschen Mathematiker-Vereinigung, 21: 103–127

- Walter, Scott (1999), "The non-Euclidean style of Minkowskian relativity" (PDF), in J. Gray, The Symbolic Universe: Geometry and Physics, Oxford University Press, pp. 91–127(see page 17 of e-link)