I Modi

I Modi (The Ways), also known as The Sixteen Pleasures or under the Latin title De omnibus Veneris Schematibus, is a famous erotic book of the Italian Renaissance in which a series of sexual positions were explicitly depicted in engravings.[2] While the original edition was apparently completely destroyed by the Catholic Church, fragments of a later edition survived. The second edition was accompanied by sonnets written by Pietro Aretino, which described the sexual acts depicted. The original illustrations were probably copied by Agostino Caracci, whose version survives.

Original edition

The original edition was created by the engraver Marcantonio Raimondi, basing his sixteen images of sexual positions on, according to the traditional view, a series of erotic paintings that Giulio Romano was doing as a commission for Federico II Gonzaga’s new Palazzo Te in Mantua.[3] Raimondi had worked extensively with Romano's master Raphael, who had died in 1520, producing prints to his design. The engravings were published by Raimondi in 1524, and led to his imprisonment by Pope Clement VII and the destruction of all copies of the illustrations. Romano did not become aware of the engravings until the poet Pietro Aretino came to see the original paintings while Romano was still working on them. Romano was not prosecuted since—unlike Raimondi—his images were not intended for public consumption. Aretino then composed sixteen explicit[4] sonnets to accompany the paintings/engravings, and secured Raimondi’s release from prison.

I Modi were then published a second time in 1527, now with the poems that have given them the traditional English title Aretino's Postures, making this the first time erotic text and images were combined, though the papacy once more seized all the copies it could find. Raimondi escaped prison on this occasion, but the suppression on both occasions was comprehensive. No original copies of this edition have survived, with the exception of a few fragments in the British Museum, and two copies of posture 1. A, possibly infringing[5] copy with crude illustrations in woodcut, printed in Venice in 1550,[6] and bound in with some contemporary texts was discovered in the 1920s, containing fifteen of the sixteen postures.[7]

Despite the seeming loss of Raimondi’s originals today, it seems certain that at least one full set survived, since both the 1550 woodcuts and the so-called Caracci suite of prints (see below) agree in every compositional and stylistic respect with those fragments that have survived. Certainly, unless the engraver of the Caracci edition had access to the British Museum’s fragments, and reconstructed his compositions from them, the similarities are too close to be accidental.[8] In the 17th century, certain Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford, engaged in the surreptitious printing at the University Press of Aretino's Postures, Aretino's De omnis Veneris schematibus and the indecent engravings after Giulio Romano. The Dean, Dr. John Fell, impounded the copper plates and threatened those involved with expulsion.[9][10] The text of Aretino’s sonnets, however, survives.

Later edition

A new series of graphic and explicit engravings of sexual positions was produced by Camillo Procaccini[11] or more likely by Agostino Carracci for a later reprint of Aretino's poems.[12][13]

Their production was in spite of their artist’s working in a post-Tridentine environment that encouraged religious art and restricted secular and public art. They are best known from the 1798 edition of the work printed in Paris as “L'Arétin d'Augustin Carrache ou Recueil de Postures Érotiques, d'Après les Gravures à l'Eau-Forte par cet Artiste Célèbre, Avec le Texte Explicatif des Sujets” (“The ‘Aretino’ of Agostino Carracci, or a collection of erotic poses, after Carracci’s engravings, by this famous artist, with the explicit texts on the subject”. "This famous artist" was Jacques Joseph Coiny (1761 - 1809).[14]

Agostino’s brother Annibale Carracci also completed the elaborate fresco of Loves of the Gods for the Palazzo Farnese in Rome (where the Farnese Hercules which influenced them both was housed). These images were drawn from Ovid’s Metamorphoses and include nudes, but (in contrast to the sexual engravings) are not explicit, intimating rather than directly depicting the act of lovemaking.

Classical guise

Several factors were used to cloak these engravings in classical scholarly respectability:

- The images nominally depicted famous pairings of lovers (e.g. Antony and Cleopatra) or husband-and-wife deities (e.g. Jupiter and Juno) from classical history and mythology engaged in sexual activity, and were entitled as such. Related to this were:

- Portraying them with their usual attributes, such as:

- Cleopatra's banquets, bottom left

- Achilles's shield and helmet, bottom left

- Hercules in his lion-skin and club

- Mars with his cuirass

- Paris as a shepherd

- Bacchus with his vine-leaf crown and (bottom right) grapes

- Referring to the best known myths or historical events in which they appeared e.g.:

- Mars and Venus under the net which her husband Vulcan has designed to catch them

- 'Aeneas' and 'Dido' in the cave in which their sexual intercourse is alluded in Aeneid, Book 4

- Theseus abandoning Ariadne on Naxos, where Bacchus finds and marries her.[15]

- the wide adultery of Julia

- Messalina's participation in prostitution, as criticised in Juvenal's Satire VI.

- Referring to other Renaissance and classical tropes in the depiction of these people and deities, such as

- The contrast between Mars's dark hair and tanned skin and his partner Venus's untanned, fair skin and fair or even blonde hair.[16]

- Jupiter's full beard [17]

- Portraying them with their usual attributes, such as:

- the frontispiece image is entitled Venus Genetrix,[18] and the goddess is nude and drawn in a chariot by doves, as in the classical sources.

- the bodies of those depicted show clear influences from classical statuary known at the time, such as:

- the over-muscled torsos and backs of the men [19](drawn from sculptures such as the Laocoön and his Sons, Belvedere Torso, and Farnese Hercules).[20]

- the women's clearly defined though small breasts (drawn from examples such as the Venus de' Medici and Aphrodite of Cnidus)[21]

- the elaborate hairstyles of some of the women, such as his Venus, Juno or Cleopatra (derived from Roman Imperial era busts such as this one).

- Portraying the action in a classical 'stage set' such as an ancient Greek sanctuary or temple.

- The large erect penis on the statue of Priapus or Pan atop a puteal in 'The Cult of Priapus' is derived from examples in classical sculpture and painting (like this fresco) which were beginning to be found archaeologically at this time.[22]

Differences from antique art

The work has various points of deviation from classical literature, erotica, mythology and art which suggest its classical learning is lightly worn, and make clear its actual modern setting:

- The male sexual partners' large penises (though not Priapus's) are the artist's invention rather than a classical borrowing - the idealised penis in classical art was small, not large (large penises were seen as comic or fertility symbols, as for example on Priapus, as discussed above).

- The title 'Polyenus and Chryseis' pairs the fictional Polyenus with the actual mythological character Chryseis.

- The title 'Alcibiades and Glycera' pairs two historical figures from different periods - the 5th century BC Alcibiades and the 4th century BC Glycera

- Female satyrs did not occur in classical mythology, yet they appear twice in this work (in 'The Satyr and his wife' and 'The Cult of Priapus').[23]

- All the women and goddesses in this work (but most clearly its Venus Genetrix) have a hairless groin (like classical statuary of nude females) but also a clearly apparent vulva (unlike classical statuary).[24]

- The modern furniture, e.g.

- The various stools and cushions used to support the participants or otherwise raise them into the right positions (e.g. here)

- The other sex aids (e.g. a whip, bottom right)

- The 16th century beds, with ornate curtains, carvings, taselled cushions, bedposts, etc.

Table of contents

Note: These prints are late 18th century re-creations of the originals (which have, in turn, influenced later erotic art, such as that of Paul Avril).[25]

| Image | No. | Title (English translation) | Male partner | Female partner | Sexual position | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 | Venus Genetrix | - | Venus Genetrix | - | - |

|

2 | Paris and Oenone | Paris | Oenone | Side-by-side, man on top | |

|

3 | Angelique and Medor | Medor | Angelique | Reverse cowgirl | Characters from Roland |

|

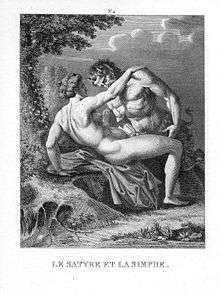

4 | The satyr and the nymph | Satyr | Nymph | Missionary position (man on top & standing, woman lying) | |

|

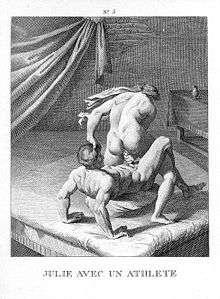

5 | Julia with an athlete | An athlete | Julia the Elder | Reverse cowgirl (woman standing) | Woman guiding in penis |

|

6 | Hercules and Deianaira | Hercules | Deianira | Standing missionary (woman supported by man) | |

|

7 | Mars and Venus | Mars | Venus | Missionary (woman on top[26]) | |

|

8 | The Cult of Priapus | Pan, or a male satyr | A female satyr | Missionary (male standing, woman sitting) | |

|

9 | Antony and Cleopatra | Mark Antony | Cleopatra | Side-by-side missionary | Woman guiding in penis |

|

10 | Bacchus and Ariadne | Bacchus | Ariadne | Leapfrog - woman entirely supported | Woman's legs up not kneeling as usual in this position |

|

11 | Polyenos and Chriseis | Polyenos (fictional) | Chryseis | Missionary (man on top and standing, woman lying) | |

|

12 | A satyr and his wife | Male satyr | Female satyr | Missionary (man standing, woman sitting) | |

|

13 | Jupiter and Juno | Jupiter | Juno | Standing (man standing/kneeling, woman supported [27]) | |

|

14 | Messalina in the booth of 'Lisica' | Brothel client | Messalina | Missionary (female lying, male standing) | |

|

15 | Achilles and Briseis | Achilles | Briseis | Standing (man entirely supporting woman) | |

|

16 | Ovid and Corinna | Ovid | Corinna | Missionary (man on top, woman guiding erect penis into her vagina) | Woman deepening penetration by having her legs outside his. |

|

17 | Aeneas and Dido [accompanied by a Cupid] | Aeneas | Dido | Fingering with left hand index finger (thus little nudity relative to other images) | Lesser nudity, though wet T-shirt effect round breasts; Cupid is erect |

|

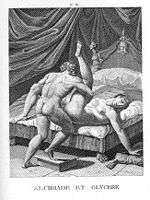

18 | Alcibiades and Glycera | Alcibiades | Glycera | Missionary (man on top and standing, woman lying and legs up) | Man also raised up to right level for vagina by right foot on step |

|

19 | Pandora | ?Epimetheus (crowned figure) | Pandora | Side by side | The boy with the candle may be a classical reference.[28] |

Footnotes

- ↑ British Museum collection database

- ↑ Walter Kendrick, The Secret Museum, Pornography in Modern Culture (1987:59)

- ↑ I Modi: the sixteen pleasures. An erotic album of the Italian renaissance / Giulio Romano … [et al.] edited, translated from the Italian and with a commentary by Lynne Lawner. Northwestern University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-7206-0724-8

- ↑ Sample quote: “both in your pussy and your behind, my cock will make me happy, and you happy and blissful”

- ↑ Max Sander, who discovered the volume, believes it to be the original 1527 edition; other scholars dispute this. vid. A History of Erotic Literature, P.J. Kearney, Macmillan 1982.

- ↑ formerly owned by Toscanini, now in a private collection; illustrations here

- ↑ The images in this edition appear in reverse next to the British Museum fragments, clear evidence that they are copied from a set of prints and not from the original paintings, since engravers and woodcutters of the period do not habitually re-reverse their images, and their quality is such that one might doubt that the artist would even have been capable of doing so.

- ↑ The Caracci suite contains eighteen images plus frontispiece, however.

- ↑ R. W. Ketton-Cremer, "Humphrey Prideaux", Norfolk Assembly (London: Faber & Faber) 1957:65.

- ↑ In the 19th century Jean Frederic Waldeck published a new edition of the work, claiming to be based on a set of tracings he made of the I Modi prints found in a convent near Palenque in Mexico, but more likely a direct copy of a combination of the BM fragments and the Caracci edition, since no such convent exists, and it is hardly likely to have harboured such material in its library.

- ↑ Francis Haskell, Taste and the Antique, (ISBN 0-300-02641-2).

- ↑ Erotica in Art — Agostino Carracci in the “History of Art”

- ↑ IRONIE, article on Carracci’s engravings (in French)

- ↑ Venus Erotic Art Museum

- ↑ Theseus's departing ship is visible on the horizon, top right.

- ↑ This trope did not fully exist in classical art - in frescoes and polychromatic sculptures, Venus was always fair-skinned, but her hair colour could vary from brown through to blond - but became fixed due to medieval and Renaissance art (e.g. Botticelli's Venus and Mars).

- ↑ A trope copied from classical and Renaissance sources.

- ↑ An attested epithet of the love/lust goddess Venus, although under that name she was more a mother goddess than a love/lust goddess.

- ↑ Also, in one or two cases, the women's, though this has far less, if any, precedent in classical sculpture.

- ↑ See also the modern phenomenon of the beefcake in erotic art.

- ↑ Though their thighs are often larger than in the examples from classical statuary.

- ↑ On the other hand, the posture in the engraving is not to be found in any known examples and is probably Caracci's own invention. Certainly archaeological examples usually (though not always) tend to show Priapus's erect and oversized penis hanging down, not standing up parallel with his chest as here, and give less importance to large or oversized testicles than in this engraving.

- ↑ Male satyrs having sex with nymphs, on the other hand, did appear in Greek myth - as has been taken up in Renaissance art - , though this was more frequently rape in the myths rather than the apparent consensual sex in the engraving.

- ↑ The men's pubic hair in the engravings does not pose a problem, since pubic hair was depicted on ancient nudes.

- ↑ "Paul Avril". arterotisme.com. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- ↑ Though lying not sitting, and with left foot supported by stool

- ↑ Or, more precisely, woman partly lying, partly supported by bed, and partly supported on left arm.

- ↑ To the classical "'Puer sufflans ignes" in Pliny. Also, the satyr who has attempted to join the lovemakers (but been kicked in the groin by the male) has an erection as a result of his voyeurism.

External links

![]() Media related to I Modi at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to I Modi at Wikimedia Commons