Thomas Hood

| Thomas Hood | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

23 May 1799 London, England |

| Died |

3 May 1845 (aged 45) London, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Period | 1820s–1840s |

| Genre | Poetry, fiction |

| Spouse | Jane Hood (née Reynolds) |

| Children | Tom Hood, Frances Freeling Broderip |

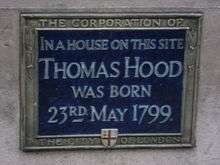

Thomas Hood (23 May 1799 – 3 May 1845) was an English poet, author and humourist, best known for poems such as "The Bridge of Sighs" and "The Song of the Shirt". Hood wrote regularly for The London Magazine, the Athenaeum, and Punch. He later published a magazine largely consisting of his own works. Hood, never robust, lapsed into invalidism by the age of 41 and died at the age of 45. William Michael Rossetti in 1903 called him "the finest English poet" between the generations of Shelley and Tennyson.[1] Hood was the father of playwright and humourist Tom Hood (1835–1874).

Early life

He was born in London to Thomas Hood and Elizabeth Sands in the Poultry (Cheapside) above his father's bookshop. Hood's paternal family had been Scottish farmers from the village of Errol near Dundee. The elder Hood was a partner in the business of Verner, Hood and Sharp, a member of the Associated Booksellers. Hood's son, Tom Hood, claimed that his grandfather had been the first to open up the book trade with America and he had great success with new editions of old books.[2]

"Next to being a citizen of the world," writes Thomas Hood in his Literary Reminiscences, "it must be the best thing to be born a citizen of the world's greatest city." On the death of her husband in 1811, his mother moved to Islington, where Thomas Hood had a schoolmaster who appreciating his talents, "made him feel it impossible not to take an interest in learning while he seemed so interested in teaching." Under the care of this "decayed dominie", he earned a few guineas — his first literary fee — by revising for the press a new edition of the 1788 novel Paul and Virginia.

Hood left his private schoolmaster at 14 years of age and was admitted soon after into the counting house of a friend of his family, where he "turned his stool into a Pegasus on three legs, every foot, of course, being a dactyl or a spondee." However, the uncongenial profession affected his health, which was never strong, and he began to study engraving. The exact nature and course of his study is unclear: various sources tell different stories. Reid emphasizes his work under his maternal uncle Robert Sands,[3] but no deeds of apprenticeship exist and we also know from his letters that he studied with a Mr Harris. Hood's daughter in her Memorials mentions her father's association with the Le Keux brothers, who were successful engravers in the City.[4]

The labour of engraving was no better for his health than the counting house had been, and Hood was sent to his father's relations at Dundee, Scotland. There he stayed in the house of his maternal aunt, Jean Keay, for some months and then, on falling out with her, moved on to the boarding house of one of her friends, Mrs Butterworth, where he lived for the rest of his time in Scotland.[5] In Dundee, Hood made a number of close friends with whom he continued to correspond for many years. He led a healthy outdoor life but also became a wide and indiscriminate reader. During his time there, Hood began seriously to write poetry and appeared in print for the first time, with a letter to the editor of the Dundee Advertiser.

Literary society

Before long Hood was contributing humorous and poetical pieces to provincial newspapers and magazines. As a proof of his literary vocation, he would write out his poems in printed characters, believing that this process best enabled him to understand his own peculiarities and faults, and probably unaware that Samuel Taylor Coleridge had recommended some such method of criticism when he said he thought, "Print settles it." On his return to London in 1818 he applied himself to engraving, which enabled him later to illustrate his various humours and fancies.

In 1821, John Scott, editor of The London Magazine, was killed in a duel, and the periodical passed into the hands of some friends of Hood, who proposed to make him sub-editor. This post at once introduced him to the literary society of the time. In becoming an associate of John Hamilton Reynolds, Charles Lamb, Henry Cary, Thomas de Quincey, Allan Cunningham, Bryan Procter, Serjeant Talfourd, Hartley Coleridge, the peasant-poet John Clare and other contributors, he gradually developed his own powers.

Family life

_from_NPG.jpg)

Hood married in May 1824,[6] and Odes and Addresses — his first volume — was written in conjunction with his brother-in-law J. H. Reynolds, a friend of John Keats. Coleridge wrote to Lamb averring that the book must be the latter's work. Also from this period are The Plea of the Midsummer Fairies (1827) and a dramatic romance, Lamia, published later. The Plea was a book of serious verse, but Hood was known as a humorist and the book was ignored almost entirely.

Hood was fond of practical jokes, which he was said to have enjoyed perpetrating on members of his family. In the Memorials there is a story of Hood instructing his wife to purchase some fish for the evening meal from a woman who regularly came to the door selling her husband’s catch. But he warns her to watch for plaice that "has any appearance of red or orange spots, as they are a sure sign of an advanced stage of decomposition." Mrs Hood refused to purchase the fish-seller's plaice, exclaiming, "My good woman… I could not think of buying any plaice with those very unpleasant red spots!" The fish-seller was amazed at such ignorance of what plaice look like.[7]

The series of the Comic Annual, dating from 1830, was a kind of publication popular at that time, which Hood undertook and continued almost unassisted for several years. Under that title he treated all the leading events of the day in caricature, without personal malice, and with an undercurrent of sympathy. Readers were also treated to an incessant use of puns, of which Hood had written in his own vindication, "However critics may take offence,/A double meaning has double sense", but as he gained experience as a writer, his diction became simpler.

Later writings

In another annual called the Gem appeared the verse story of Eugene Aram. Hood started a magazine in his own name, which was mainly sustained by his own activity. He conducted the work from a sick-bed from which he never rose, and there also composed well-known poems such as the "The Song of the Shirt", which appeared anonymously in the Christmas number of Punch, 1843 and was immediately reprinted in The Times and other newspapers across Europe. It was dramatised by Mark Lemon as The Sempstress, printed on broadsheets and cotton handkerchiefs, and was highly praised by many of the literary establishment, including Charles Dickens. Likewise "The Bridge of Sighs" and "The Song of the Labourer", which were also translated into German by Ferdinand Freiligrath. These are plain, solemn pictures of conditions of life, which appeared shortly before Hood's own death in May 1845.

Hood was associated with the Athenaeum, started in 1828 by James Silk Buckingham, and he was a regular contributor for the rest of his life. Prolonged illness brought on straitened circumstances. Application was made by a number of Hood's friends to Sir Robert Peel to place Hood's name on the civil pension list with which the British state rewarded literary men. Peel was known to be an admirer of Hood's work and in the last few months of Hood's life he gave Jane Hood the sum of £100 without her husband's knowledge to alleviate the family's debts.[8] The pension that Peel's government bestowed on Hood was continued to his wife and family after his death. Jane Hood, who also suffered from poor health and had expended tremendous energy tending to her husband in his last year, died only 18 months later. The pension then ceased, but Lord John Russell, grandfather of the philosopher Bertrand Russell, made arrangements for a £50 pension for the maintenance of Hood's two children, Frances and Tom.[9]

Nine years later, a monument raised by public subscription in Kensal Green Cemetery was unveiled by Richard Monckton Milnes.

Thackeray, a friend of Hood's, gave this assessment of him: "Oh sad, marvellous picture of courage, of honesty, of patient endurance, of duty struggling against pain! ... Here is one at least without guile, without pretension, without scheming, of a pure life, to his family and little modest circle of friends tenderly devoted."[10]

The house where Hood died, No. 28 Finchley Road, in the St. John's Wood area of London, now has a blue plaque.[11]

Examples of his works

Hood wrote humorously on many contemporary issues. One of the most important issues in his time was grave robbing and selling of corpses to anatomists (see West Port murders). On this serious and perhaps cruel issue, he wrote wryly,

Don’t go to weep upon my grave,

And think that there I be.

They haven’t left an atom there

Of my anatomie.

November in London is usually cool and overcast, and in Hood's day subject to frequent fog and smog. In 1844 he wrote,

No sun - no moon!

No morn - no noon -

No dawn - no dusk - no proper time of day.

No warmth, no cheerfulness, no healthful ease,

No comfortable feel in any member -

No shade, no shine, no butterflies, no bees,

No fruits, no flowers, no leaves, no birds -

November!

An example of Hood's reflective and sentimental verse is the famous "I Remember, I Remember", excerpted here:

I remember, I remember

The house where I was born,

The little window where the sun

Came peeping in at morn;

He never came a wink too soon

Nor brought too long a day;

But now, I often wish the night

Had borne my breath away.I remember, I remember

The roses, red and white,

The violets, and the lily-cups

Those flowers made of light!

The lilacs where the robin built,

And where my brother set

The laburnum on his birth-day,

The tree is living yet!I remember, I remember

Where I used to swing,

And thought the air must rush as fresh

To swallows on the wing;

My spirit flew in feathers then

That is so heavy now,

And summer pools could hardly cool

The fever on my brow.I remember, I remember

The fir trees dark and high;

I used to think their slender tops

Were close against the sky:

It was childish ignorance,

But now 'tis little joy

To know I'm farther off from Heaven

Than when I was a boy.

Hood’s most widely known work during his lifetime was "The Song of the Shirt", a verse lament for a London seamstress compelled to sell shirts she had made, the proceeds of which lawfully belonged to her employer, in order to feed her malnourished and ailing child. Hood’s poem appeared in one of the first editions of Punch in 1843 and quickly became a public sensation, being turned into a popular song and inspiring social activists in defence of countless industrious labouring women living in abject poverty. An excerpt:

With fingers weary and worn,

With eyelids heavy and red,

A woman sat, in unwomanly rags,

Plying her needle and thread--

Stitch! stitch! stitch!

In poverty, hunger, and dirt,

And still with a voice of dolorous pitch

She sang the "Song of the Shirt.""Work! work! work!

While the cock is crowing aloof!

And work—work—work,

Till the stars shine through the roof!

It's Oh! to be a slave

Along with the barbarous Turk,

Where woman has never a soul to save,

If this is Christian work!"

Modern references

- Metro-Land - John Betjeman (1973)

- "Opus 4" - The Art of Noise (album: In Visible Silence, 1986)

- The Piano - Jane Campion (1993)

- So Much Blood - Simon Brett (1976)

Works by Thomas Hood

The list of Hood's separately published works is as follows:

- Odes and Addresses to Great People (1825)

- Whims and Oddities (two series, 1826 and 1827)

- The Plea of the Midsummer Fairies, hero and Leander, Lycus the Centaur and other Poems (1827), his only collection of serious verse

- The Dream of Eugene Aram, the Murderer (1831)

- Tylney Hall, a novel (3 vols., 1834)

- The Comic Annual (1830–1842)

- Hood's Own, or, Laughter from Year to Year (1838, second series, 1861)

- Up the Rhine (1840)

- Hood's Magazine and Comic Miscellany (1844–1848)

- National Tales (2 vols., 1837), a collection of short novelettes, including "The Three Jewels".

- Whimsicalities (1844), with illustrations from John Leech's designs; and many contributions to contemporary periodicals.

References

- ↑ Rossetti, W. M. Biographical Introduction, The Poetical Works of Thomas Hood. (London, 1903).

- ↑ J. C. Reid, p. 10.

- ↑ Reid, p. 19.

- ↑ Memorials, p. 5.

- ↑ His living situation in Dundee was pieced together by George Maxwell in Hood in Scotland. See particularly Chapter III.

- ↑ In Memorials, p. 17, his daughter Francis gives the date of her parents' marriage as 5 May 1824. Reid, p. 67, on the other hand, gives 5 May of the following year.

- ↑ Memorials, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Clubbe, p. 181.

- ↑ Clubbe, p. 196.

- ↑ Reid, p. 235.

- ↑ "Thomas Hood - Blue plaque". Open Plaques. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

Further reading

- John Clubbe. Victorian Forerunner; The Later Career of Thomas Hood (Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina, 1968).

- Frances Hood, The Memorials of Thomas Hood - Vol. 1 and The Memorials of Thomas Hood - Vol. 2 (Ticknor & Fields, Boston, 1860).

- Walter Jerrold. Thomas Hood; His Life and Times (John Lane, New York, 1909).

- Alex Elliot (Ed.) Hood in Scotland (James P. Matthew & Co., Dundee, 1885).

- J. C. Reid. Thomas Hood (Routledge & Kegan Paul, New York, 1963).

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Thomas Hood |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Thomas Hood |

- Thomas Hood at the Poetry Foundation

- Works by Thomas Hood at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Thomas Hood at Internet Archive

- Works by Thomas Hood at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Poetical Works of Thomas Hood at The University of Adelaide Library

- Thomas Hood biography & selected writings at gerald-massey.org.uk

- "Archival material relating to Thomas Hood". UK National Archives.

- "Thomas Hood", George Saintsbury in Macmillan's Magazine, Vol. LXII, May to Oct. 1890, pp. 422–430

- Flint, Joy. Hood, Thomas (1799–1845). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online ed.(accessed 26 November 2010)