Type III hypersensitivity

| Type III hypersensitivity | |

|---|---|

| |

| Immune complex | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| MeSH | D007105 |

Type III hypersensitivity occurs when there is accumulation of immune complexes (antigen-antibody complexes) that have not been adequately cleared by innate immune cells, giving rise to an inflammatory response and attraction of leukocytes. Such reactions progressing to the point of disease produce immune complex diseases.

Signs and symptoms

Type III hypersensitivity occurs when there is an excess of antigen, leading to small immune complexes being formed that fix complement and are not cleared from the circulation. It involves soluble antigens that are not bound to cell surfaces (as opposed to those in type II hypersensitivity). When these antigens bind antibodies, immune complexes of different sizes form.[1] Large complexes can be cleared by macrophages but macrophages have difficulty in the disposal of small immune complexes. These immune complexes insert themselves into small blood vessels, joints, and glomeruli, causing symptoms. Unlike the free variant, a small immune complex bound to sites of deposition (like blood vessel walls) are far more capable of interacting with complement; these medium-sized complexes, formed in the slight excess of antigen, are viewed as being highly pathogenic.[2]

Such depositions in tissues often induce an inflammatory response,[3] and can cause damage wherever they precipitate. The cause of damage is as a result of the action of cleaved complement anaphylotoxins C3a and C5a, which, respectively, mediate the induction of granule release from mast cells (from which histamine can cause urticaria), and recruitment of inflammatory cells into the tissue (mainly those with lysosomal action, leading to tissue damage through frustrated phagocytosis by PMNs and macrophages).[4]

The reaction can take hours, days, or even weeks to develop, depending on whether or not there is immunological memory of the precipitating antigen. Typically, clinical features emerge a week following initial antigen challenge, when the deposited immune complexes can precipitate an inflammatory response. Because of the nature of the antibody aggregation, tissues that are associated with blood filtration at considerable osmotic and hydrostatic gradient (e.g. sites of urinary and synovial fluid formation, kidney glomeruli and joint tissues respectively) bear the brunt of the damage. Hence, vasculitis, glomerulonephritis and arthritis are commonly associated conditions as a result of type III hypersensitivity responses.[5]

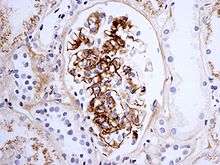

As observed under methods of histopathology, acute necrotizing vasculitis within the affected tissues is observed concomitant to neutrophilic infiltration, along with notable eosinophilic deposition (fibrinoid necrosis). Often, immunofluorescence microscopy can be used to visualize the immune complexes.[5] Skin response to a hypersensitivity of this type is referred to as an Arthus reaction, and is characterized by local erythema and some induration. Platelet aggregation, especially in microvasculature, can cause localized clot formation, leading to blotchy hemorrhages. This typifies the response to injection of foreign antigen sufficient to lead to the condition of serum sickness.[4]

Examples

Some clinical examples:

| Disease | Target antigen | Main effects | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Nuclear antigens |

| |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | Antibody complexes: specifically IgM to IgG | ||

| Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis | Streptococcal cell wall antigens |

| |

| Polyarteritis nodosa | Hepatitis B virus surface antigen |

| |

| Reactive arthritis | Several bacterial antigens |

| |

| Serum sickness | Various |

| |

| Arthus reaction | Various |

| |

| Farmer's Lung | Inhaled antigens (often mould or hay dust) |

| |

| Henoch–Schönlein purpura | Unknown, likely respiratory pathogen | ||

| Unless else specified in boxes, then ref is:[6] | |||

Other examples are:

- Subacute bacterial endocarditis[7]

- Symptoms of malaria

See also

References

- ↑ "Hypersensitivity reactions". Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ↑ Parham, Peter (2009). "12". The Immune System (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Garland Science. p. 390.

- ↑ "Chapter 19". Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- 1 2 Parham, Peter (2009). "12". The Immune System (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Garland Science. p. 389.

- 1 2 Kumar, Vinay (2010). "6". Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Mechanisms of Disease (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 204–205.

- ↑ Table 5-3 in: Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson. Robbins Basic Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2973-7. 8th edition.

- ↑ "Definition: immune complex disease from Online Medical Dictionary".