History of the Inga dams

This is a history of the Inga dams, chronicling the various studies, plans, and projects that have aimed to harness the energy of the Congo River at the site of the Inga Falls, located north of Matadi in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The immense potential of the Inga Falls was recognized in the early 1900s, though the first major hydroelectric project, initiated by the Belgians, did not come until the late 1950s. Two dams were built at the site during the rule of President Mobutu Sese Seko: Inga I was commissioned in 1972 and Inga II in 1982. Since then proposals have been put forth for an Inga III as well as a Grand Inga, which if built, would be the largest hydroelectric facility in the world.

Early study

The hydropower potential of the Congo River was recognized quite early on, at a time when colonial control was expanding over Africa and rivers were first being harnessed to generate electricity. One early report on this potential came via the United States Geological Survey in 1921; their findings concluded that the Congo basin in its entirety possessed “more than one-fourth of the world’s potential water power”. Regarding the Inga Falls location specifically, this was highlighted just four years later by the Belgian soldier, mathematician, and entrepreneur Colonel Van Deuren. He would continue survey work around Inga Falls, and during the 1920s and 1930s there was some movement towards further study of the area’s potential by the group Syneba (1929–1939), yet the outbreak of World War II and the dissolution of Syneba put a temporary end to progress on the site.[1]

Belgian plan

Despite the lack of progress during and in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, the tantalizing possibilities offered by the Inga Falls remained prominent in engineers’ minds. The 1954 book Engineers’ Dreams listed a host of massive projects that could theoretically be accomplished (among them the future Channel Tunnel), the largest being an Inga Dam that would create a lake stretching into the Sahara Desert.[2]

Before Congolese independence, the Belgians still harbored the hope of constructing a massive Inga development project to generate electricity for heavy industry.[3] Among those industries discussed were “aluminum, ferro-alloys, the treatment of ores, paper, and a plant for the separation of isotopes.”[4] Their vision, at least publicly, was bold, with one authority comparing the potential industrial development in the Congo to the German Ruhr.[4] There was an important American connection the project in the form of Clarence E. Blee, one of five foreigners on a 10-person study of the Inga site in 1957 and the chief engineer of the United States’ foray into federal electrical and industrial development, the Tennessee Valley Authority.[4] This study would play a central role in convincing the Belgian authorities to set an Inga dam in motion.

An Inga scheme, loosely reported as consisting of a “series of power stations and dams”, was finally passed by the Belgian Cabinet on November 13, 1957, and a group was slated to be created in order to study the possible uses of the project’s electricity and the ways in which to fund it. The Cabinet’s plan was estimated at the time to cost US$3.16 billion and was expected to generate 25,000 MW.[5]

A report from late April 1958 stated that excavation work would hopefully begin by midyear, with 1964/1965 as the year set to bring the initial stage to completion. Plans called for three stages of construction, beginning with a 1,500 MW plant with a $320 million price tag, then twice that capacity, and eventually the 25,000 MW originally approved. Industrial development would advance in step, helped by a start price of $0.002 per kwh, producing 500,000 tons of aluminum with the construction of the first plant and eventually aiming for a final production goal six times that. An international syndicate named Aluminga, comprising a number of European and North American firms, was already organizing to realize this. Funding was an issue, especially once the Belgians realized that they could not accomplish such a project alone. Possible investors cited by the press included the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the European Investment Bank.[6]

In February 1959 a group of prominent American investors including David Rockefeller visited the Inga Falls,[7] though construction was continually being pushed back from original estimates, then slated for 1961 or later.[8]

Congolese independence from Belgium did not suddenly erase the importance of Inga development. Belgian authorities were still pushing the project while negotiating independence with Congolese delegates, with Minister Raymond Scheyven proposing a joint Congolese-Belgian company that would fund an Inga dam. This was not a minor idea, but the main project in a five-year Congolese development plan he proposed.[9] That advice was apparently not heeded, as newly elected Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba signed a fifty-year contract with the Wall Street-based Congo International Management Corporation to develop the Congo on July 22, 1960, with an Inga project and associated aluminum production at the top of the list.[10] PM Lumumba later backtracked and claimed that the deal was "only an agreement in principle",[11] but regardless he was deposed by Army Chief of Staff Mobutu Sese Seko less than two months later.

Inga I and Inga II

Despite the ensuing period of instability, rebellions, and UN interventions in the first half of the 1960s, it did not dampen leaders' hopes to harness the rapids of the Congo River. From the wreckage of the Belgian departure and the subsequent turmoil emerged Mobutu Sésé Seko, who seized full power for himself in November 1965 and would remain the Congo’s authoritarian president until May 1997. It was during his reign that the first and so far only projects were built to generate power from the Inga Falls.

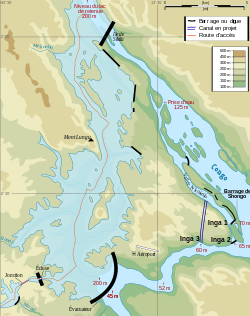

Inga I was the first project brought to completion. A feasibility study was conducted by the Italian firm SICAI in 1963, which recommended the dam support domestic industrialization as opposed to export focused industry.[12] Funded mainly by the government, construction took place from 1968 to 1972, leaving a six-turbine plant generating 351 MW.[13] This electricity was mainly fed to the populated areas around it and downstream; its successor was explicitly for mining activity in the south.

Inga II was the second hydro project built at the site just south of Inga I. Even with just eight turbines, it was built to produce 1,424 MW, and was completed a full decade after Inga I.[13]

Inga-Shaba power line

In order to connect the power generating capacity at Inga with the copper and cobalt mines located near the Zambian border in Shaba Province (now Katanga), a new project aimed to build the longest high-voltage direct current power line in existence, bypassing local communities and converting into alternating current at its final destination. The various groups involved had economic as well as political agendas; while Western investors and the Congolese government wished to support the Shaba mines during a period of elevated copper prices, the government also wanted to consolidate its power over the secessionist southern province, and the West had an interest in seeing the Congo stay firmly in the anti-communist camp. The cost for the project was constantly revised upward, eventually reaching $500 million over budget. A mix of private and public groups provided the financing, notably Citibank, Manufacturers Hanover Trust, and the U.S. Export-Import Bank, and it was the storied Boise, Idaho-based company, Morrison-Knudsen, that was contracted to do the work.[14][15]

In 1980, the costs of the Inga-Shaba power line totaled 24% of Congo’s debt, which along with corruption, other wasteful spending, and bad decision-making, led to a debt crisis and the intervention of foreign experts.[16] As of 1999, Congo still owed the U.S. Export-Import Bank over $900 million, leaving American taxpayers unpaid.[17] As the Inga-Shaba line neared completion in the early 1980s, many news articles poured scorn on the project. One from the Washington Post juxtaposed its failure with a successful Peace Corps project to improve the Congolese diet, noting that, “the grandiose project has so far turned out to be a white elephant, while the low-key fish-farming endeavor has already made visible improvements in the lives of several thousand people in a similar period of time.”[15] Gécamines, the state-owned mining company in Shaba that was originally founded in 1906 by the Belgians, ended up still mainly using hydroelectricity supplied locally, and thus the Inga-Shaba line found itself being used at a mere third of capacity. Furthermore, the structure itself has been degraded as local peoples have used its metal bars for a variety of domestic needs.[18]

Future

Rehabilitation

The DRC has faced the problem of rehabilitating the two existing dams, which have fallen into disrepair and operate far below original capacity at roughly 40%, or just over 700 MW combined.[13] In May 2001 Siemens was reportedly negotiating with the government over a billion-dollar partnership that would involve restoration and modernization of the DRC’s electrical grid, including the rehabilitation of the two existing Inga power plants,[19] though work was delayed.[20] In mid-2003 there was also a report that the World Bank had signed a $450 million contract with Siemens to improve water and electrical distribution in the DRC, including rehabilitation of the two Inga projects (reported at the time to be at 30% capacity) and a second electrical line from Inga to the capital.[21] It is unclear what transpired concerning these contracts.

Separately in May 2005 the Canadian company MagEnergy signed an agreement with SNEL to rehabilitate some of Inga II’s turbines, with a completion goal of 2009.[22] Actual work to rehabilitate Inga II finally began April 27, 2006, just under a year after the initial agreement with MagEnergy was signed.[23] This first phase, which involved fixing a single 168 MW turbine and other emergency repair work, was reported 90% complete in April 2009, and the second phase (four other turbines) was estimated to take five additional years.[24] However, there is doubt over whether the government accepts the validity of the contract, and in the meantime the Canadian company First Quantum was hired to rehabilitate two separate Inga II turbines.[25] To carry out the repairs, the SNEL has received funding from the Regional and Domestic Power Markets Development Project, which is itself supported by the World Bank, African Development Bank, and European Investment Bank.[13]

Inga III and Grand Inga

One enthusiastic backer of Inga development has been South Africa. In July 1999, newly elected South African President Thabo Mbeki gave a speech to the Organisation of African Unity, highlighting development of the Inga Falls for hydropower as an example of necessary development of Africa’s economic infrastructure.[26] For South Africa’s public utility Eskom, Inga fit into a broader plan to turn an interconnected African grid into an electricity-exporting powerhouse, eventually supplying Europe and the Middle East.[27] In 2002 Inga was highlighted by the AU’s New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD)[28] and Eskom was reported to be investigating a $6 billion run-of-the-river type Inga project which would be developed by an Eskom and Hydro-Québec-led consortium of national utility companies.[29]

Such a consortium, dubbed the Western Power Corridor (Westcor) was finally organized in February 2003. Involving five of the region’s major utility companies (Eskom, SNEL, Angola’s Empresa Nacional de Electricidade, Namibia’s NamPower, and the Botswana Power Corporation) it projected initial costs at $1.5 billion and the eventual construction of a 44,000 MW run-of-the-river project.[30] A memorandum of understanding for Westcor was finally signed on October 22, 2004, for the construction of a 3,400 MW Inga III.[31] The following February Eskom unveiled a new $50 billion run-of-the-river scheme.[32] That September 2005 a shareholder agreement for Westcor was signed, giving each party 20%.[33]

The DRC appeared to move away from the regional development approach offered by Westcor and instead manage the construction of Inga III on its own. In June 2009 it opened bidding for a $7 billion, 4320 MW Inga III project.[34] Snubbing Westcor, the DRC chose BHP Billiton, which intended to use 2,000 MW for itself, notably for an aluminum smelter.

See also

References

- ↑ Showers, Kate B. (2009). "Congo River's Grand Inga hydroelectricity scheme: linking environmental history, policy and impact". Water History. 1 (1): 31–58. doi:10.1007/s12685-009-0001-8.

- ↑ Leonard, Jonathan N. (May 30, 1954). "New Sources of Power". The New York Times Book Review. p. 14.

- ↑ "Economy Gaining in Belgian Congo". The New York Times. September 28, 1957. p. 27.

- 1 2 3 Holz, Peter (March 1958). "More Power Lights "Darkest Africa"". Popular Mechanics. 109 (3): 232.

- ↑ "Congo Plan Approved". The New York Times. November 14, 1957. p. 18.

- ↑ Waggoner, Walter H. (April 26, 1958). "Belgium Rushes Huge Power Project on the Congo". The New York Times. p. 24.

- ↑ Bracker, Milton (February 11, 1959). "U.S. Bankers View Project in Congo". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Belgian Congo Plant Delayed". The New York Times. April 7, 1959.

- ↑ Gilroy, Harry (February 17, 1960). "Congo Cautioned On Its Economy". The New York Times.

- ↑ Tanner, Henry (July 23, 1960). "Congo Signs Pact With U.S. Concern To Tap Resources". The New York Times.

- ↑ "CONGO: Where's the War?". TIME. August 8, 1960. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ↑ Young, Crawford; Turner, Thomas (1985). The Rise and Decline of the Zairian State. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 298–301.

- 1 2 3 4 "Inga 1 and Inga 2 dams". International Rivers. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ↑ Randa, Jonathan C. (April 28, 1977). "Mobuto Riding High, But Possibility Raised of Guerilla Warfare". The Washington Post. p. A26.

- 1 2 Ross, Jay (April 25, 1982). "A Tale of Two Projects: One Winner, One Loser". The Washington Post. p. C5.

- ↑ Dash, Leon (January 1, 1980). "Mobutu Mortgages Nation's Future". The Washington Post. p. A1.

- ↑ Mufson, Steven (December 16, 1999). "Abroad at Home: The Foreign Affairs Community – Ex-Im Bank Aims to Do More in Africa". The Washington Post. p. A37.

- ↑ Winternitz, Helen (1987). East Along the Equator: A Journey Up the Congo and into Zaire. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 175.

- ↑ "Siemens Plans to Invest $1 billion in RDC Electronics Network". European Report. May 24, 2001.

- ↑ "Grand Schemes on the Congo". IT Week. February 3, 2004.

- ↑ Misser, Francois (June 1, 2003). "Siemens flags off massive DRC project". African Business.

- ↑ "MagEnergy Concludes Inga II Rehabilitation Agreement". Marketwire. May 31, 2005.

- ↑ "MagEnergy Announces Start of Inga II Hydroelectric Plant Work Program". Marketwire. May 1, 2006.

- ↑ "MagEnergy nears completion of unit rehab at DR Congo's 1,424-MW Inga 2". Hydroworld.com. April 20, 2009. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- ↑ "Everyone Plugs Into Inga". Africa Energy Intelligence. February 11, 2009.

- ↑ Mbeki, Thabo (July 20, 1999). "Podium: The globalization of Africa". London: The Independent. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- ↑ Hale, Briony (October 17, 2002). "Africa's grand power exporting plans". BBC News. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- ↑ "Hard Talk, Charm Carries the Day for NEPAD". All Africa. June 13, 2002.

- ↑ "Eskom's Secret Project". Africa Energy Intelligence. May 19, 2002.

- ↑ "Pan African Consortium for Inga". Africa Energy Intelligence. February 19, 2003.

- ↑ Thomson, Alistair (October 22, 2004). "Africa plans new Congo generator, seeks investment". Reuters.

- ↑ Vasagar, Jeevan (February 25, 2005). "Could a $50bn plan to tame this mighty river bring electricity to all of Africa?". London: The Guardian. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- ↑ "Landmark Agreement to Satisfy Regional Power Needs". All Africa. September 8, 2005.

- ↑ "Congo opens bidding for Inga 3 hydro dam investors". Reuters. June 19, 2009. Retrieved November 17, 2009.