Irish heraldry

Irish heraldry is the forms of heraldry, such as coats of arms, in Ireland. Since 1 April 1943 it is regulated in the Republic of Ireland by the Office of the Chief Herald of Ireland and in Northern Ireland by Norroy and Ulster King of Arms. Prior to that heraldry on the whole island of Ireland was a function of the Ulster King of Arms, a crown office dating from 1552. Despite its name the Ulster King of Arms was based in Dublin.

Office of the Chief Herald of Ireland

The Office of the Chief Herald of Ireland, sometimes incorrectly called the Office of Arms, is the Republic of Ireland's authority on all heraldic matters relating to Ireland and is located at the National Library of Ireland.

It has jurisdiction over:

- All Irish citizens, male or female

- Persons normally resident in Ireland

- Persons living abroad who are of provable Irish descent in either the paternal or maternal line

- Persons with significant links to Ireland

- Corporate bodies within Ireland and corporate bodies with significant links to Ireland but based in countries with no heraldic authority.

Sept arms

A distinctive feature of Irish heraldry is acceptance of the idea of sept arms, which belong to descendants, not necessarily of a determinate individual, but of an Irish sept, the chieftain of which, under Irish law, was not necessarily a son of the previous chieftain but could be any member of the sept whose grandfather had held the position of chieftain (tanistry).[1] A member of the particular sept has the right to display the arms of that sept, a right that on the contrary does not belong to people of the same surname who belong to a different sept.[2] For example, a person from the O'Kelly sept of Ui Máine may display the arms of that sept, but a Kelly of the Meath or Kilkenny septs cannot.

Proponents of English heraldry and those who hold a documented right to arms see sept arms as controversial,[2] but the Irish Genealogical Office (previously known as the Office of Arms)[3] "holds that any member of a sept may display the arms of that sept (as distinct from personally 'bearing' the arms, as on stationery, silver, or other such use, [for] only the grantee and his descendants may 'bear' the arms)". Edward McLysaght, the first Chief Herald of Ireland after independence and the author of several works on Irish families, introduced this distinction.[4]

Pat Brennan writes that we simply do not have enough evidence to be doctrinaire about clan or sept arms. He adds: "Naturally the idea of clan or sept arms is anathema to English heraldic practice (like a lot of other Gaelic Irish customs)." However, to show that it is not totally unique, he cites H. Bedington & P. Gwynn-Jones, Heraldry (Greenwich, CT 1993): "In eastern Europe whole groups of families or territorial areas adopted the same armorial bearings (in) a form of clan affiliation." Brennan particularly points to heraldry in Poland, where arms may pertain to a whole group of families. In one extreme Polish case almost 600 families bear the same symbol - a horse-shoe enclosing a cross.[2]

Even after the introduction of English heraldry into Ireland and the setting up of arrangements for regulating it, the arms registered were undifferentiated, that is, they show no signs of the practice of changing a tincture or adding some symbol to personalize those of a particular individual. Brennan concludes that, rather than being the property of an individual, the arms belonged either to the sept as a whole or to the chief or to all members of the ruling élite in the sept. The hundreds of people claiming the right to arms indicate, Brennan says, either that they had used those arms for some time, or that the arms did not belong personally to the chief or that they were obviously based on the ancient clan system, so that the chief could not complain of their use by others.[2]

Terminology

In English, achievements of arms are usually described (blazoned) in a specialized jargon that uses derivatives of French terms. In Irish, however, achievements of arms are described in language which, while formal and different from plain language, is not quite so opaque as Anglo-Norman terminology is in English. Nevertheless, Irish heraldic terminology is a kind of specialized jargon. Examples used since 1943 include the use of Irish gorm and uaine for blue and green, as compared to the French-derived azure and vert used in English blazon.[5]

| Tinctures | Paints or Colours | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escutcheons |  |

|

|

|

|

| English | Azure | Gules | Vert | Purpure | Sable |

| Irish | Gorm | Dearg | Uaine | Corcra | Dubh |

| Tinctures | Metals | Furs | |||

| Escutcheons |  |

|

|

|

|

| English | Or | Argent | Ermine | Vair | |

| Irish | Ór (órga) | Airgead (airgidí) | Eirmín | Véir | |

| Ordinaries Ríphíosaí |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Pale | Fess | Bend | Bend sinister |

| Irish | Cuaille | Balc | Bandán | Clébhandán |

| Ordinaries Ríphíosaí |

|

|

.svg.png) |

.svg.png) |

| English | Chevron | Chief | Cross | Saltire |

| Irish | Rachtán | Barr | Cros | Sailtír |

| Ordinaries Ríphíosaí |

|

|

|

|

| English | Pall | Pall subverted | Pile | Bordure |

| Irish | Gabhal | Gabhal aisiompaithe | Ding | Imeallbhord |

| Division of the field |  |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Party per fess | Party per pale | Party per bend sinister | Quarterly | Quarterly charged with an inescutcheon |

| Irish | Gearrtha | Deighilte | Cléroinnte | Ceathair-roinnte | Ceathair-roinnte móide lársciath |

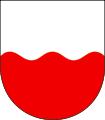

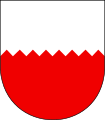

| Lines of division |  |

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Wavy | Indented | Engrailed | Invected |

| Irish | Camógach | Eangach | Clasach | Dronnógach |

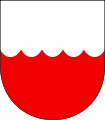

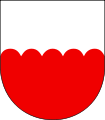

| Lines of division |  |

|

|

|

| English | Nebuly | Embattled | Dovetailed | Potenty |

| Irish | Néalach | Táibhleach | Déadach | Cathógach |

Coat of arms of Ireland

.svg.png)

The Coat of arms of Ireland is blazoned as Azure a harp Or, stringed argent – a gold harp with silver strings on a blue background. The harp, and specifically the cláirseach (or Gaelic harp), has long been Ireland's heraldic emblem. It appears on the coat of arms which were officially registered as the arms of the state of Ireland on 9 November 1945. The harp has been recognised as a symbol of Ireland since the 13th century.[6]

References

- ↑ McLaughlin Arms and Motto

- 1 2 3 4 Pat Brennan, "Gaelic Irish Heraldry and Heraldic Practice"

- ↑ Genealogical Society of Ireland, "Developing a Plan to Capture the Full Value of Our Geneaogical Heritage", p. 26

- ↑ Michael J. O'Shea, James Joyce and Heraldry (SUNY Press 1986 ISBN 978-0-88706270-4), p. 180

- ↑ Williams, Nicholas (2001). Armas: Sracfhéachaint ar Araltas na hÉireann. Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. pp. vii, 224, 39 Plates.

- ↑ Civic Heraldry of Ireland, National arms of Ireland, Ralf Hartemink, 1996