Italia-class ironclad

_at_La_Spezia_1897.jpg) | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Italia class |

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | Caio Duilio class |

| Succeeded by: | Ruggiero di Lauria class |

| Built: | 1876–1887 |

| In service: | 1885–1921 |

| Completed: | 2 |

| Retired: | 2 |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Type: | ironclad battleship |

| Displacement: |

|

| Beam: | 22.54 m (74.0 ft) |

| Draft: | 8.75 m (28.7 ft) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | 4 shafts, 4 compound engines |

| Speed: | 17.8 knots (33.0 km/h; 20.5 mph) |

| Range: | ca. 5,000 nautical miles (9,260 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 669–701 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

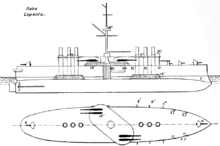

The Italia class was a class of two ironclad battleships built for the Italian Regia Marina (Royal Navy) in the 1870s and 1880s. The two ships—Italia and Lepanto—were designed by Benedetto Brin, who chose to discard traditional belt armor entirely, relying on a combination of very high speed and extensive internal subdivision to protect the ships. This, along with their armament of very large 17-inch (430 mm) guns, has led some naval historians to refer to the Italia class as prototypical battlecruisers.

Despite serving for over thirty years, the ships had uneventful careers. They spent their first two decades in service with the Active and Reserve Squadrons, where they were primarily occupied with training maneuvers. Lepanto was converted into a training ship in 1902 and Italia was significantly modernized in 1905–08 before also becoming a training ship. They briefly saw action during the Italo-Turkish War, where they provided gunfire support to Italian troops defending Tripoli. Lepanto was discarded in early 1915, though Italia continued on as a guard ship during World War I, eventually being converted into a grain transport. She was ultimately broken up for scrap in 1921.

Design

Starting in the 1870s, following the Italian fleet's defeat at the Battle of Lissa, the Italians began a large naval expansion program, at first aimed at countering the Austro-Hungarian Navy.[2] The Italias were the second class of the programme, which also included the Caio Duilio, designed in the mid-1870s by Insp Eng Benedetto Brin. The ships were authorized in 1875, with funding allocated to begin construction the following year.[3] They were faster and more seaworthy than the preceding Caio Duilio class, owing to their higher freeboard. Brin intended them to be capable of fighting successfully against any foreign warship in service, and so he opted for very large guns for the main battery.[4]

Brin originally planned for the ships to displace 13,850 tons (14,066 tonnes), to have a secondary armament of eighteen 6-inch (152-mm) guns, and to carry 3,000 tons (3,047 tonnes) of coal for increased range over that of the Caio Duilio class. In the end, however, the 6-inch (152-mm) armament was reduced to eight 6-inch (152 mm) and the coal capacity to 1,700 tons (1,727 tonnes) on 15,000 tons (15,237 tonnes) displacement.[4] The number of 6-inch (152-mm) guns was reduced because it was found that the additional guns could not have been manned when the 17-inch (432-mm) guns were in use.[5] Unlike other ships built at the time, the two Italia-class ironclads dispensed with vertical belt armor. Brin believed that contemporary steel alloys could not effectively defeat armor-piercing shells of the day. Additionally, fitting belt armor on a ship the size of Italia would cause a prohibitive increase in displacement, and so he discarded it completely in favor of a thin armored deck.[6]

They were very large and fast warships for their time, displacing over 15,000 tons at full load; Italia could make 17.8 knots (33.0 km/h), while Lepanto could achieve 18.4 knots (34.1 km/h).[6] Other ironclads of the era could not make more than 15 knots (28 km/h).[4] Their high speed, powerful main battery, and thin armor protection has led to many naval historians to characterize the ships as proto-battlecruisers.[7]

General characteristics and machinery

The ships of the Italia class were 122 meters (400 ft) long between perpendiculars and 124.7 m (409 ft) long overall. Italia had a beam of 22.54 m (74.0 ft), while Lepanto was slightly narrower, at 22.34 m (73.3 ft). The ships had a draft of 8.75 m (28.7 ft) and 9.39 m (30.8 ft), respectively. Italia displaced 13,678 metric tons (13,462 long tons; 15,077 short tons) normally and up to 15,407 t (15,164 long tons; 16,983 short tons) at full load, while Lepanto displaced 13,336 t (13,125 long tons; 14,700 short tons) normally and 15,649 t (15,402 long tons; 17,250 short tons) fully laden. Italia's hull was constructed of iron and steel covered by wood, which in turn was covered by zinc, while Lepanto's hull was made entirely of steel. Both ships were fitted with a single military mast with fighting tops placed directly amidships; a small hurricane deck connected the ships' funnels and the mast. They had a crew of 669–701 officers and men.[6] The ships had 25 feet (7.6 m) of freeboard.[5]

Their propulsion system consisted of four compound steam engines each driving a single screw propeller, with steam supplied by eight coal-fired, oval boilers and sixteen fire-tube boilers. Italia's boilers were trunked into six funnels, placed in two sets of three all on the centerline. Lepanto only had four funnels in two pairs; during Italia's refit in 1905–08, her funnels were reduced to an identical arrangement. Italia's engines produced a top speed of 17.8 knots (33.0 km/h; 20.5 mph) from 11,986 indicated horsepower (8,938 kW); Lepanto was faster, with a top speed of 18.4 knots (34.1 km/h; 21.2 mph) from 15,797 ihp (11,780 kW). The ships could steam for 5,000 nautical miles (9,300 km; 5,800 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[6]

Armament

Italia and Lepanto each carried a main armament of four 17-inch (432 mm) guns; Italia received three 26-caliber guns and one 27-caliber gun, while Lepanto was equipped entirely with 27-caliber guns.[6] These guns were the A 1882 model, and they fired a 2,000-pound (910 kg) shell at a muzzle velocity of around 1,837 feet per second (560 m/s). Their rate of fire was very slow, taking eight minutes to reload after each shot.[8] The guns were mounted in pairs en echelon amidships in a single, large, diagonal, oval barbette, with one pair of guns on a turntable to port and the other to starboard; the port pair was mounted aft of the starboard pair. The magazine was below the armored deck, and ammunition was brought up to the main guns via an armored trunk.[4] The ships' high freeboard allowed the main guns to be mounted 33 feet (10 m) above the waterline, and the design and location of the barbette and turntables gave the guns good fields of fire.[5]

The ships carried a secondary battery of seven 6 in (152 mm) 26-caliber guns and four 4.7 in (119 mm) 32-caliber guns, though Lepanto had an eighth 6 in gun.[6] The 6 in gun fired a variety of shells, including 102 lb (46 kg) armor-piercing shells, while the 4.7 in guns fired 36 lb (16 kg) shells.[9] Their secondary batteries were revised over the course of their careers; both ships received two 75 mm (3.0 in) guns, twelve 57 mm (2.2 in) 40-caliber guns, twelve 37 mm (1.5 in) revolver cannon, and two machine guns. As was customary for capital ships of the period, they carried four 14 in (356 mm) torpedo tubes; later in her career, Italia received two additional tubes, while Lepanto had hers removed in 1910.[6] The torpedoes carried a 125 kg (276 lb) warhead and had a range of 600 m (2,000 ft).[10]

Armor

Instead of belt armour the ships were protected by an armored deck that was 4 in (102 mm) thick.[6] The armored deck sloped downward to meet the ships' sides at a point 6 feet (1.8 m) above the waterline and combined with two bulkheads that ran the entire length of the ships, set back several feet from the side, and numerous other bulkheads interspersed among the two main bulkheads to create a hull extensively divided into watertight compartments. The resulting "cellular raft" of small compartments was designed to detonate shells before they could penetrate very far into the ships; confining the resulting explosion and flooding to limited areas, dampening and containing the effect. The ships' conning tower was armored with 4 in of steel plate and the barbette had 19 in (483 mm) of compound armor to protect the guns. The bases of the funnels received 16 in (406 mm) of armor.[4][6]

Construction

| Name | Builder[6] | Laid down[6] | Launched[6] | Completed[6] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italia | Regio Cantiere di Castellammare di Stabia | 3 January 1876 | 29 September 1880 | 16 October 1885 |

| Lepanto | Cantiere navale fratelli Orlando | 4 November 1876 | 17 March 1883 | 16 August 1887 |

Service history

Italia and Lepanto spent the first decade of their careers alternative between the Active and Reserve Squadrons of the Italian fleet, and were primarily occupied with training exercises. As Italy was a member of the Triple Alliance at the time, the simulated opponent in these maneuvers was typically France; during the 1893 annual fleet maneuvers, both ships served in the squadron simulating an attack on the Italian coast.[11] In June 1897, Lepanto steamed to Britain to represent Italy at the Fleet Review for Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee, held on the 26th of the month.[12] The ships continued to alternate between the squadrons, with 1897 and 1898 in the Reserve,[13][14] and 1899 in the Active Squadron.[15] During this period, the Italian Navy considered rebuilding the ships along the same lines as the ironclad Enrico Dandolo, but the project proved to be too costly, and by 1902 the plan was abandoned.[16]

Lepanto was removed from front-line service in 1902 and converted into a gunnery training ship; to aid in this task, the ship received a variety of light weapons that trainees would go on to use in the fleet.[6][17] Italia was modernized in 1905–08, losing two of her funnels and several of her small-caliber guns; from 1909 to 1910, she served as a torpedo training ship.[6] Both ships were reactivated in September 1911 after the outbreak of the Italo-Turkish War, initially assigned to the 5th Division.[18] After the capture of Tripoli in October, Italia and Lepanto were sent to the city to provide gunfire support for the soldiers defending it.[19] Lepanto was stricken from the naval register on 26 May 1912, before the war ended, but she was reinstated on 13 January 1913 as an auxiliary. She did not remain in service long, being stricken again on 27 March 1915 and broken up for scrap.[6][17]

Italia continued in service through Italy's participation in World War I, from May 1915 to November 1918, initially as a guard ship in Brindisi. In December 1917, she was taken to La Spezia, where she was converted into a grain carrier, serving briefly with the Ministry of Transport in June 1919 before being transferred to the State Railways in July. The ship returned to the Navy in January 1921, but was stricken in November that year and sold for scrap.[6][17]

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Italia class battleship. |

- ↑ Figures are for Italia

- ↑ Greene & Massignani, p. 394

- ↑ Sondhaus (1994), p. 50

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gibbons, p. 106

- 1 2 3 Gibbons, p. 107.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Gardiner, p. 341

- ↑ Sondhaus (2001), p. 112

- ↑ Friedman, p. 231

- ↑ Friedman, pp. 239–240

- ↑ Friedman, p. 347

- ↑ Clarke & Thursfield, pp. 202–203

- ↑ Diehl, p. 82

- ↑ Garbett 1897, p. 789

- ↑ Garbett 1898, p. 200

- ↑ Brassey, p. 72

- ↑ Garbett 1902, p. 1076

- 1 2 3 Gardiner & Gray, p. 255

- ↑ Beehler, p. 10

- ↑ Beehler, p. 47

References

- Beehler, William Henry (1913). The History of the Italian-Turkish War: September 29, 1911, to October 18, 1912. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute.

- Brassey, Thomas A., ed. (1899). The Naval Annual (Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.).

- Clarke, George S.; Thursfield, James R. (1897). The Navy and the Nation. London: John Murray.

- Diehl, S. W. B. (1898). "Great Britain's Naval Review at Spithead". Notes on Naval Progress. Washington, DC: Office of Naval Intelligence: 81–94.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Garbett, H., ed. (1897). "Naval Notes". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. XLI (232): 779–792. OCLC 8007941.

- Garbett, H., ed. (1898). "Naval Notes – Italy". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher. XLII: 199–204. OCLC 8007941.

- Garbett, H., ed. (1902). "Naval and Military Notes – Italy". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher. XLVI: 1072–1076. OCLC 8007941.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-133-5.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1984). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1922. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3.

- Gibbons, Tony (1983). The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers: A Technical Directory of All the World's Capital Ships From 1860 to the Present Day. London: Salamander Books, Ltd. ISBN 0-86101-142-2.

- Greene, Jack & Massignani, Alessandro (1998). Ironclads at War: The Origin and Development of the Armored Warship, 1854–1891. Pennsylvania: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-938289-58-6.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval Warfare, 1815–1914. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21478-5.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918. West Lafayette, In: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-034-9.