Champ Clark

| Champ Clark | |

|---|---|

| |

| 36th Speaker of the United States House of Representatives | |

|

In office April 4, 1911 – March 4, 1919[1] | |

| President |

William Howard Taft Woodrow Wilson |

| Preceded by | Joseph G. Cannon |

| Succeeded by | Frederick H. Gillett |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Missouri's 9th district | |

|

In office March 4, 1893 – March 3, 1895 March 4, 1897 – March 2, 1921[1] | |

| Preceded by |

Seth W. Cobb William M. Treloar |

| Succeeded by |

William M. Treloar Theodore W. Hukriede |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

James Beauchamp Clark March 7, 1850 Lawrenceburg, Kentucky |

| Died |

March 2, 1921 (aged 70) Washington, D.C. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Genevieve Davis Bennett Clark |

| Alma mater |

Bethany College University of Cincinnati College of Law |

| Profession | Law |

| Religion | Disciples of Christ[2] |

James Beauchamp "Champ" Clark (March 7, 1850 – March 2, 1921) was a prominent American politician in the Democratic Party from the 1890s until his death. A Representative of Missouri from 1893 to 1895 and from 1897 to 1921, he served as the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1911 to 1919. He was an unsuccessful candidate for the Democratic nomination for President in 1912.[1]

Early life

Clark was born in Lawrenceburg, Kentucky, to John Hampton Clark and Aletha Beauchamp. Through his mother, he was the first cousin twice removed of the famous lawyer-turned-murderer Jereboam O. Beauchamp. He is also directly descended from the famous John Beauchamp (Plymouth Company) through his mother. He graduated from Bethany College (West Virginia) where he was initiated into Delta Tau Delta Fraternity, and Cincinnati Law School and moved to Missouri in 1875, and opened a law practice the following year. He eventually settled in Bowling Green, Missouri, the county seat of Pike County. He served a principal at Marshall College (now Marshall University) from 1873 to 1874.

Political career

Clark was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1892. After a surprise loss in 1894 to William M. Treloar, he regained the seat in 1896, and remained in the House until his death, the day before he was to leave office.

Clark ran for House Minority Leader in 1903 but was defeated by John Sharp Williams of Mississippi. After Williams ran for the Senate in 1908, Clark ran again for the position and won. When the Democrats won control of the House in 1911, Clark became Speaker. In 1911, Clark gave a speech that helped to decide the election in Canada. On the floor of the House, Clark argued for the recent Canadian–American Reciprocity Treaty and declared: "I look forward to the time when the American flag will fly over every square foot of British North America up to the North Pole."[3]

Clark went on to suggest in his speech that the treaty was the first step towards the end of Canada, a speech that was greeted with "prolonged applause" according to the Congressional Record.[4] The Washington Post reported, "Evidently, then, the Democrats generally approved of Mr. Clark's annexation sentiments and voted for the reciprocity bill because, among other things, it improves the prospect of annexation."[4] The Chicago Tribunal condemned Clark in an editorial, predicting that Clark's speech might have fatally damaged the treaty in Canada; "He lets his imagination run wild like a Missouri mule on a rampage. Remarks about the absorption of one country by another grate harshly on the ears of the smaller."[4] The Conservative Party of Canada, which opposed the treaty, won the Canadian election in large part because of Clark's speech.

In 1912, Clark was the frontrunner for the Democratic presidential nomination, coming into the convention with a majority of delegates pledged to him, but he failed to receive the necessary two-thirds of the vote on the first several ballots. After lengthy negotiation, clever management by supporters of New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson, with widespread allegations of influence by special interests, delivered the nomination instead to Wilson.

Clark's Speakership was notable for two things. Clark's skill from 1910 to 1914 in maintaining party unity to block William Howard Taft's legislation and then pass Wilson's. Also, Clark split the party in 1917 and 1918, when he opposed Wilson's decision to bring the United States into World War I.

In addition, Clark opposed the Federal Reserve Act, which concentrated financial power in the hands of eastern banks (mostly centered in New York City). Clark's opposition to the Federal Reserve Act is said to be the reason that Missouri is the only state granted two Federal Reserve Banks (one in St. Louis and one in Kansas City).

Clark was defeated in the Republican landslide of 1920 and died shortly thereafter in his home in Washington, DC.

Champ Clark is the namesake of the small community of Champ, Audrain County, Missouri.[5]

Personal life

Clark married to Genevieve Bennett Clark on December 14, 1881. Together, they had two children, Joel Bennett Clark and Genevieve Clark Thomson. Bennet served as a United States Senator from Missouri from 1933 to 1945. Genevieve was a suffragette and a candidate for the House of Representatives for Louisiana.[6]

Gallery

Speaker Clark's official portrait

Speaker Clark's official portrait Speaker Clark (left) with Representative James R. Mann of Illinois

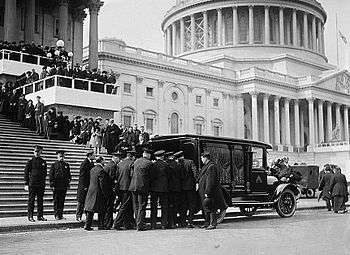

Speaker Clark (left) with Representative James R. Mann of Illinois Champ Clark's casket being loaded into a hearse outside the United States Capitol, flag at half staff, March 5, 1921

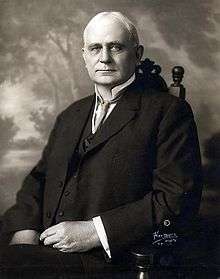

Champ Clark's casket being loaded into a hearse outside the United States Capitol, flag at half staff, March 5, 1921 Clark about a month before his death.

Clark about a month before his death.- Clark's former residence in Washington, D.C.

Champ Clark and daughter Genevieve

Champ Clark and daughter Genevieve

References

- Specific

- 1 2 3 Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- ↑ "The Religious Affiliation of U.S. Congressman Rep. Champ Clark". Adherents.com. Retrieved 2011-04-13.

- ↑ Allan, Chantal Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Athabasca: Athabasca University Press, 2009 p. 17.

- 1 2 3 Allan, Bomb Canada: And Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media page 18.

- ↑ "Audrain County Place Names, 1928-1945 (archived)". The State Historical Society of Missouri. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ Waal, Carla; Korner, Barbara Oliver (1997-01-01). Hardship and Hope: Missouri Women Writing about Their Lives, 1820-1920. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 9780826211200.

- General

- Garraty, John A. and Mark C. Carnes. American National Biography, vol. 4, "Clark, Champ". New York : Oxford University Press, 1999.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Champ Clark. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Champ Clark |

- United States Congress. "Champ Clark (id: C000437)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- James Beauchamp Clark at Find a Grave

- James Beauchamp Clark article from the Crystal Reference Encyclopedia (former Cambridge Encyclopedia for Cambridge University Press)

- James Beauchamp Clark's Signature on the 17th Amendment to the constitution Image of original document

| United States House of Representatives | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Seth W. Cobb |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Missouri's 9th congressional district 1893–1895 |

Succeeded by William M. Treloar |

| Preceded by William M. Treloar |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Missouri's 9th congressional district 1897–1921 |

Succeeded by Theodore W. Hukriede |

| Preceded by John Sharp Williams |

Minority Leader of the United States House of Representatives 1908–1911 |

Succeeded by James Robert Mann |

| Preceded by James Robert Mann |

Minority Leader of the United States House of Representatives 1919–1921 |

Succeeded by Claude Kitchin |

| Preceded by Joseph G. Cannon |

Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives April 4, 1911 – March 4, 1913; April 7, 1913 – March 4, 1915; December 6, 1915 – March 4, 1917; April 2, 1917 – March 4, 1919 |

Succeeded by Frederick H. Gillett |