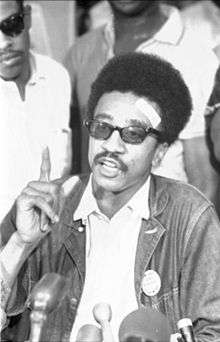

H. Rap Brown

| Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin | |

|---|---|

H. Rap Brown in 1967 | |

| Born |

October 4, 1943 Baton Rouge, Louisiana |

| Residence |

Tucson USP (sentenced by the state of Georgia[1]) |

| Known for | 5th Chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee |

| Term | May 1967 – June 1968 |

| Predecessor | Stokely Carmichael |

| Successor | organization collapsed |

| Religion | Islam |

| Spouse(s) | Karima Al-Amin |

Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin (born October 4, 1943, as Hubert Gerold Brown), also known as H. Rap Brown, was chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the 1960s, and during a short-lived (six months) alliance between SNCC and the Black Panther Party, he served as their minister of justice. He is perhaps most famous for his proclamations during that period that "violence is as American as cherry pie" and that "If America don't come around, we're gonna burn it down." He is also known for his autobiography Die Nigger Die!. He is currently serving a life sentence for murder following the 2000 shooting of two Fulton County Sheriff's deputies. One deputy, Ricky Kinchen, died in the shooting.

Activism

Brown was born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. He became known as H. Rap Brown during the early 1960s. His activism in the Civil Rights Movement included involvement with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), of which he was named chairman in 1967. That same year, he was arrested in Cambridge, Maryland, and charged with inciting to riot after he gave a speech there.

He appeared on the Federal Bureau of Investigation's Ten Most Wanted List after avoiding trial on charges of inciting riot and of carrying a gun across state lines. His attorneys in the gun violation case were civil rights advocate Murphy Bell of Baton Rouge and the self described "radical lawyer" William Kunstler. Brown was originally to be tried in Cambridge, but the trial was moved to Bel Air, Maryland.

On March 9, 1970, two SNCC officials, Ralph Featherstone and William ("Che") Payne, died on U.S. Route 1 south of Bel Air, when a bomb on the front floorboard of their car exploded, completely destroying the car and dismembering both occupants. The bomb's origin is disputed: some say it was planted in an assassination attempt, and others say Payne was intentionally carrying it to the courthouse where Brown was to be tried. The next night the Cambridge courthouse was bombed.[2]

Brown disappeared for 18 months, and then was arrested after a reported shootout with officers after what was said to be an attempted robbery of a bar in New York City. He spent five years (1971–76) in Attica Prison after a robbery conviction. While in prison, Brown converted to Islam and changed his name from Hubert Gerold Brown to Jamil Abdullah al-Amin. After his release, he opened a grocery store in Atlanta, Georgia, and became a Muslim spiritual leader and community activist preaching against drugs and gambling in Atlanta's West End neighborhood.

It has since been alleged that al-Amin's life changed again when he allegedly became affiliated with the "Dar ul-Islam Movement".[3]

2000 arrest and conviction

On March 16, 2000, in Fulton County, Georgia, Sheriff's deputies Ricky Kinchen and Aldranon English went to al-Amin's home to execute an arrest warrant for his failure to appear in court after a citation for speeding and impersonating a police officer. It was believed that he was an honorary police officer in a town in Alabama, and showed his honorary badge to gain the sympathy of the officer citing him. After determining that the home was unoccupied, the deputies drove away and were shortly passed by a black Mercedes headed for the home. Kinchen (the more-senior deputy) noted the suspect vehicle, turned the patrol car around, and drove up to the Mercedes, stopping nose-to-nose. English approached the Mercedes and told the single occupant to show his hands. The occupant opened fire with a .223 rifle. English ran between the two cars while returning fire from his handgun, but was hit four times. Kinchen was shot with the rifle and a 9 mm handgun. The next day, Kinchen died of his wounds at Grady Memorial Hospital. English survived his wounds, and identified al-Amin as the shooter from six photos he was shown while recovering in the hospital. Both of the Sheriff's deputies al-Amin was convicted of shooting were black, which undermined al-Amin's racial conspiracy theory defense at trial.[4]

Shortly after the shootout, al-Amin fled to White Hall, Alabama, where he was tracked down by U.S. Marshals and arrested by law-enforcement officers after a four-day manhunt. Al-Amin was wearing body armor at the time of his arrest, and officers found a 9 mm handgun and .223 rifle near his arrest location. Firearms Identification testing showed that the weapons were the ones used to shoot Kinchen and English. Later, al-Amin's black Mercedes was found riddled with bullet holes.[5] His lawyers argued he was innocent of the shooting. Al-Amin’s fingerprints were not found on the murder weapon, and he was not wounded in the shooting, as one of the deputies said the shooter was. The deputy also said the killer's eyes were gray, but Al-Amin's are brown.[6]

On March 9, 2002, nearly two years after the shooting, al-Amin was convicted of 13 criminal charges, including Kinchen's murder. Four days later, he was sentenced to life in prison without possibility of parole.[7] He was sent to Georgia State Prison, the state's maximum-security facility near Reidsville, Georgia.

At his trial, prosecutors pointed out that al-Amin had never provided an alibi for his whereabouts at the time of the shootout, nor any explanation for fleeing the state afterwards. He also did not explain the bullet holes in his car, nor why the weapons used in the shootout were found near him during his arrest. In May 2004, the Supreme Court of Georgia unanimously ruled to uphold al-Amin's conviction.[8]

In August 2007, al-Amin was transferred to federal custody, as Georgia officials decided he was too high-profile for the Georgia prison system to handle. He was moved to a federal transfer facility in Oklahoma pending assignment to a federal penitentiary. On October 21, 2007, al-Amin was transferred to the ADX Florence supermax prison in Florence, Colorado.[9] On July 18, 2014, having been diagnosed with multiple myeloma, al-Amin was transferred to Butner Federal Medical Center in North Carolina.[10] As of 2016, he is incarcerated at the United States Penitentiary, Tucson.[1]

Bibliography

- Die Nigger Die!: A Political Autobiography, Westport, CT: Lawrence Hill Books, 1969; London: Allison & Busby, 1970. Online.

- Revolution by the Book: The Rap Is Live, 1993.

See also

- African-American Civil Rights Movement (1896–1954)

- Timeline of the African-American Civil Rights Movement (1954–68)

Notes

- 1 2 "Federal Bureau of Prisons Inmate Locator". Federal Bureau of Prisons. Retrieved 2016-10-26. (BOP Register Number 99974-555)

- ↑ Holden, Todd (March 23, 1970). "Bombing: A Way of Protest and Death". Time. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- ↑ Black America, Prisons, and Radical Islam (PDF). Center for Islamic Pluralism. September 2008. ISBN 978-0-9558779-1-9. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- ↑ Ariel Hart, "Court in Georgia Upholds Former Militant's Conviction", The New York Times, May 25, 2004

- ↑ "Ex-Black Panther convicted of murder". CNN. March 19, 2002. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ↑ "Muslim Cleric Jamil Al-Amin Is Convicted of Murder; Prosecutors Urge Jurors to Sentence The Muslim Spiritual Leader to Death". DemocracyNOW Independent Global News. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Deputy Sheriff Ricky Leon Kinchen". Officer Down Memorial Page. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved January 8, 2008.

- ↑ "Georgia Justices Uphold Al-Amin Murder Verdict"

- ↑ Bluestein, Greg (August 3, 2007). "1960s Militant Moved to Federal Custody". ABC News. Archived from the original on April 11, 2008. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ↑ Imam Jamil Al-Amin (H. Rap Brown) transferred to Butner Federal Medical Center, N.C.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: H. Rap Brown |

- Video with Stokely Carmichael, Oakland 1968

- Online audiorecordings and video of H. Rap Brown via UC Berkeley Black Panther site

- Bio and Sound Clip, History Channel

- Biography of Ricky Kinchen from the Southern Poverty Law Center report 15 Law Enforcement Officers Murdered by Domestic Extremists since the Oklahoma City Bombing