John Brown (Covenanter)

John Brown (1627–1685), also known as the Christian Carrier, was a Protestant Covenanter from Priesthill farm, a few miles from Muirkirk in Ayrshire, Scotland. He became a Presbyterian martyr in 1685.

Among the numerous executions carried out by the government during The Killing Time of the 1680s, the allegations of brutality make this event one of the most controversial illustrations of the character of John Graham of Claverhouse, afterwards Viscount Dundee.

Background

In order to protect the Presbyterian polity and Calvinist doctrine of the Church of Scotland, the pre-Restoration government of Scotland[1] signed the 1650 Treaty of Breda with King Charles II to crown him king and support him against the English Parliamentary forces. At his Restoration in 1660, the King renounced the terms of the Treaty and his Oath of Covenant, which the Scottish Covenanters saw as a betrayal. The Rescissory Act 1661 repealed all laws made since 1633, effectively ejecting 400 Ministers from their livings, restoring patronage in the appointment of Ministers to congregations and allowing the King to proclaim the restoration of Bishops to the Church of Scotland. The Abjuration Act of 1662 ..was a formal rejection of the National Covenant of 1638 and the Solemn League and Covenant of 1643. These were declared to be against the fundamental laws of the kingdom. The Act required all persons taking public office to take an oath of abjuration not to take arms against the king, and rejecting the Covenants. This excluded most Presbyterians from holding official positions of trust. [2]

The resulting disappointment with Charles II's religious policy became civil unrest and erupted in violence during the early summer of 1679 with the assassination of Archbishop Sharp, Drumclog and the Battle of Bothwell Bridge. The Sanquhar Declaration of 1680 effectively declared the people could not accept the authority of a King who would not recognise their religion, nor commit to his previous oaths. In February 1685 the King died and was succeeded by his Roman Catholic brother the Duke of York, as King James VII.

Life

John Brown lived in a remote farm called Priesthill 55°33′38″N 4°00′53″W / 55.560464°N 4.014718°WCoordinates: 55°33′38″N 4°00′53″W / 55.560464°N 4.014718°W, in the upland parish of Muirkirk in Kyle, Ayrshire, where he cultivated a small piece of ground and acted as a carrier. Wodrow[3] describes him as 'of shining piety,' and one who had 'great measures of solid digested knowledge, and had a singular talent of a most plain and affecting way of communicating his knowledge to others, he had employed his leisure in instructing youths.' [4] He had fought with the Covenanters at the battle of Bothwell Bridge (1679); and was on intimate terms with the leaders of the persecuted party. In 1682, Alexander Peden, one of the chief of these, united him in marriage to his second wife, Marion Weir, and on this occasion Peden, according to Walker,[5] foretold the husband's early and violent end. 'Keep linen by you for his winding-sheet,' he added.[6]

He was shot on the morning of 1 May 1685 in a summary execution instigated by John Graham of Claverhouse under the emergency powers given him by the Privy Council[7] to suppress insurrection in the South West of the country.

Death

In 1685, Brown was captured (along with his nephew, one 'John Brownen') by a Troop of Horse under the command of Graham of Claverhouse, Brown's house was searched where 'bullets, match and treasonable documents' were found.[8] Brown was offered the chance to take the Oath of Abjuration. Brown refused to swear the oath which was designed to be repugnant to Covenanters and thereby a "sieve, the mesh of which would winnow the loyal from the disloyal".[9]

At the time, failure to take the Oath was a capital offence, defying the King was high treason; this was a fact of which Brown was well aware. 'John Brownen' then made testimony that John Brown had in fact been 'in armes' at Drumclog and Bothwell Bridge. An underground house was discovered which contained weapons which Brown stated belonged to his uncle - John Brown.[10][11]

Controversy

Much of what we know of his life has come from contemporary accounts of the dramatic events of the morning on which he died. A number of clearly Polemical accounts were produced in the years following while eyewitnesses remained living and their accounts could be assembled.[12] These (except Howie) were written after the Revolution but while the Jacobite threat was still alive. It is these accounts which have been influential in setting a reputation of cruelty on the part of Claverhouse.

A second level of detail was published in the late 19th century by revisionists chiefly concerned with reassessing and redefining Claverhouse's reputation.[13] Mark Napier's work is an overt paean on the life of his hero Claverhouse, while Charles Sandford Terry takes a more modern approach to the source documents, but expresses his views nevertheless. These both publish a letter from Claverhouse[14] to the Duke of Queensberry, the Lord High Treasurer, the head of the Scottish government, in which Claverhouse defends his actions taken in executing John Brown. Not surprisingly, he is sparse on detail of the summary execution. 'I caused shoot him dead, which he suffered very inconcernedly.' This contrasts with his great detail on the reasons and evidence against Brown.

Napier and Terry cite this letter as an example of Claverhouse's professionalism in law enforcement, simply following orders. However, Wodrow et al. do not dispute Brown was technically guilty of the draconian laws, but question the morality of the high-handed laws and highlight the cruelty of Claverhouse in carrying out the sentence on the spot, in front of his house, infant son and pregnant wife.

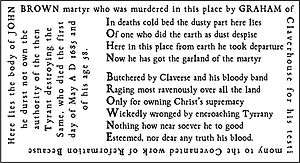

A memorial was erected after his death and a more permanent stone plinth put in place in 1828. The site, on the remote hillside above Muirkirk is still the destination of visitors to pay their respects and sits on an ancient upland path that runs to Lesmahagow.

Scenes from his Death

Several stories were published by Covenanting commentators after his death, each with slightly different detail. Patrick Walker describes six troopers who shot Brown, and that "the most part of the bullets fell upon his head", Wodrow says that the dragoons were so moved to tears after Brown prayed that they refused to obey Claverhouse's orders and that he himself had to shoot - for fear of mutiny - adds Howie.

While Alexander Shields writing only five years later[15] mentions that Brown was shot in front of his house in the presence of his wife, Wodrow says his wife was pregnant and that his infant son was also present. Walker makes no mention of his wife being pregnant but that his son and a child from a previous marriage were present.

While critics of the Covenanters point to the inconsistency of the detail as proof of their fabrication, the sheer number of similar cases painstakingly recorded by these authors within living memory of the events and the wide popularity and readership of these publications confirms, at least, the deep effect these events had on a nation who, for a hundred years had subscribed to a settled religion that was now under threat by the stroke of the King's legislating pen.

Significance

Controversy over the details notwithstanding, the sheer number of events like this and their continued power to excite controversy shows a broader significance beyond the immediate religious arguments. As part of the political ferment leading to the Revolution in both Scotland and England, they represent the emergence of the people's voice against government policy and the development of modern ideas of democracy and the limits of government in the face of popular opposition. These views eventually supplanted the Stuart dynasty's view of the Divine right of kings.

Notes

- ↑ http://bcw-project.org/church-and-state/the-commonwealth/treaty-of-breda

- ↑ http://www.thereformation.info/abjurationOath.htm

- ↑ The history of the sufferings of the church of Scotland from the restoration to the revolution, 1721

- ↑ Wodrow, vol.iv

- ↑ Patrick Walker, Six Saints of the Covenant, 1727

- ↑ Watt 1886.

- ↑ 23 April 1685, Hist. MSS Comm. Reept. XV, Ptf viii, pp91-98

- ↑ Mark Napier - Memorials and letters illustrative of life and times of John Graham of Claverhouse, viscount Dundee (1859)

- ↑ Charles Sandford Terry - "John Graham of Claverhouse, viscount of Dundee, 1648-1689" (1905) p 194

- ↑ Charles Sandford Terry - "John Graham of Claverhouse, viscount of Dundee, 1648-1689" (1905)

- ↑ Mark Napier - Memorials and letters illustrative of life and times of John Graham of Claverhouse, viscount Dundee (1859)

- ↑ Wodrow's History of the Sufferings of the Church of Scotland. Edin. 1721-2; Patrick Walker's Life of Peden, (published within "Six Saints of the Covenant". 1727, Glasgow; Thomson's edition of A Cloud of Witnesses (1713), Edin. 1871, gives (pp. 574-5) an account of the monument, with copy of inscription; Daniel Defoe's 1717 book "Memoirs of the Church of Scotland can also be included in this group as an exercise in polemic; as can John Howie (biographer)'s scholarly "Scots Worthies" (1775) which, while written 100 years later, mention's in passing the story of Alexander Peden's portentous prophecy at John Brown's marriage p511

- ↑ Napier's Life and Times of John Graham, Edin. 1862, contains Claverhouse's Report, together with a defence of his conduct; Charles Sandford Terry - "John Graham of Claverhouse, viscount of Dundee, 1648-1689" (1905)

- ↑ Hist. MSS Comm. Rept XV, Ptf. viii, p299, dated 3 May 1985, from Glaston, Ayshire

- ↑ Alexander Shields, A short Memorial of the sufferings of the Presbyterians in Scotland, 1690

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Watt, Francis (1886). "Brown, John (1627?-1685)". In Stephen, Leslie. Dictionary of National Biography. 7. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Watt, Francis (1886). "Brown, John (1627?-1685)". In Stephen, Leslie. Dictionary of National Biography. 7. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

References

- Mark Napier - Memorials and letters illustrative of life and times of John Graham of Claverhouse, viscount Dundee (1859)

- Charles Sandford Terry - "John Graham of Claverhouse, viscount of Dundee, 1648-1689" (1905)

- Mowbray Morris - "John Graham" (1887)

- Alistair and Henrietta Tayler, John Graham of Claverhouse. London: Duckworth (1939).