John Oldcastle

| John Oldcastle | |

|---|---|

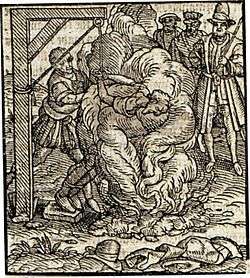

John Oldcastle being burnt for insurrection and Lollard heresy | |

| Born |

1360/78 ? Herefordshire, England |

| Died |

14 December 1417 London, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Religion | Christian (Lollard) |

Sir John Oldcastle (died 14 December 1417) was an English Lollard leader. Being a friend of Henry V, he long escaped prosecution for heresy. When convicted, he escaped from the Tower of London and then led a rebellion against the King. Eventually, he was captured and executed in London. He formed the basis for William Shakespeare's character John Falstaff, who was originally called John Oldcastle.

Family

Oldcastle's date of birth is unknown, although dubious and possibly apocryphal sources place it variously at 1360 or 1378.[1] His father was Richard Oldcastle of Almeley in northwest Herefordshire. His grandfather, also called John Oldcastle, was Herefordshire's MP during the latter part of the reign of King Richard II.

Early life

Oldcastle is first mentioned in two separate documents in 1400, first as a plaintiff in a suit regarding the advowson of Almeley church, and again as serving as a knight under Lord Grey of Codnor in a military expedition to Scotland.[1] In the next few years Oldcastle held notable positions in the Welsh campaigns of King Henry IV of England against Owain Glyndŵr, including captaincy first over Builth Castle in Brecknockshire and then over Kidwelly.[2]

Oldcastle represented Herefordshire as a "knight of the shire" in the parliament of 1404, later serving as a justice of the peace, and was High Sheriff of Herefordshire in 1406–07.[2]

In 1408 he married Joan, the heiress of Cobham — his third marriage, and her fourth.[2] This resulted in a significant improvement of his fortune and status, as the Cobhams were "one of the most notable families of Kent".[3] The marriage brought Oldcastle a number of manors in Kent, Norfolk, Northamptonshire and Wiltshire, as well as Cooling Castle, and from 1409 until his accusation in 1413 he was summoned to parliament as Lord Cobham.[3]

At some point in his military career Oldcastle became a trusted supporter of Henry, Prince of Wales, later to become King Henry V, who regarded Sir John as "one of his most trustworthy soldiers".[4] Oldcastle was a member of the expedition which the young Henry sent to France in 1411 in a successful campaign to assist the Burgundians in the Armagnac-Burgundian Civil War.[4]

Lollardy

Lollardy had many supporters in Herefordshire, and Oldcastle himself had adopted Lollard doctrines before 1410, when the churches on his wife's estates in Kent were laid under interdict for unlicensed preaching. In the convocation which met in March 1413, shortly before the death of Henry IV, Oldcastle was at once accused of heresy.

But his friendship with the new King Henry V prevented any decisive action until convincing evidence was found in one of Oldcastle's books, which was discovered in a shop in Paternoster Row, London. The matter was brought before the King, who desired that nothing should be done until he had tried his personal influence. Oldcastle declared his readiness to submit to the king "all his fortune in this world" but was firm in his religious beliefs.

When Oldcastle fled from Windsor Castle to his own castle at Cowling, Henry at last consented to a prosecution. Oldcastle refused to obey the archbishop's repeated citations, and it was only under a Royal Writ that he at last appeared before the ecclesiastical court on 23 September 1413.

In a confession of his faith he declared his belief in the sacraments and the necessity of penance and true confession, but he would not assent to the orthodox doctrine of the sacrament as stated by the Bishops, nor admit the necessity of confession to a priest. He also said the veneration of images was "the great sin of idolatry". On 25 September he was convicted as a heretic.

King Henry V was still anxious to find a way of escape for his old comrade, and granted a respite of forty days. Before that time had expired, Oldcastle escaped from the Tower by the help of one William Fisher, a parchmentmaker of Smithfield.[5]

Open rebellion

Oldcastle now put himself at the head of a widespread Lollard conspiracy, which assumed a definite political character. The plan was to seize the King and his brothers during a Twelfth-night mumming at Eltham, and establish some sort of commonwealth. Oldcastle was to be Regent, the king, nobility and clergy placed under restraint, and the abbeys dissolved and their riches shared out. King Henry, forewarned of their intention by a spy, moved to London, and when the Lollards assembled in force in St Giles's Fields on 10 January they were easily dispersed by the king and his forces.[6]

Oldcastle himself escaped into deepest northwest Herefordshire, and for nearly four years avoided capture.

Apparently he was privy to the Southampton Plot in July 1415, when he stirred some movement in the Welsh Marches. On the failure of the scheme he went again into hiding. Oldcastle was no doubt the instigator of the abortive Lollard plots of 1416, and appears to have intrigued with the Scots also.

Capture and death

In November 1417 his hiding-place was at last discovered and he was captured by Edward Charleton, 5th Baron Cherleton. Some historians believed he was captured in the upland Olchon Valley of western Herefordshire adjacent to the Black Mountains, Wales, not far from the village of Oldcastle itself in his family's old heartlands. Modern historians believe that he was hiding with some Lollard friends at a glade on Pant-mawr farm in Broniarth, in Wales called Cobham's Garden. The principal agents in the capture were four of the tenants of Edward Charleton, 5th Baron Cherleton, Ieuan and Sir Gruffudd Vychan, sons of Gruffudd ap Ieuan, being two of them. Oldcastle who was "sore wounded ere he would be taken", was brought to London in a horse-litter. The reward for his capture was awarded to Baron Cherleton, but he died before receiving it, though a portion was paid to his widow in 1422.

On 14 December he was formally condemned, on the record of his previous conviction, and that same day was hanged in St Giles's Fields, and burnt "gallows and all". It is not clear whether he was burnt alive.

Literary portrayals

His heretical opinions and early friendship with Henry V created a traditional scandal which long continued. In the old play The Famous Victories of Henry V, written before 1588, Oldcastle figures as the Prince's boon companion. When Shakespeare adapted that play in Henry IV, Part 1, Oldcastle still appeared, but when the play was printed in 1598, the name was changed to Falstaff (modelled after John Fastolf), in deference to one of Oldcastle's descendants, Lord Cobham. Though the fat knight still remains "my old lad of the Castle", the stage character has nothing to do with the Lollard leader. In Henry IV, Part 2 an epilogue emphasises that Falstaff is not Oldcastle: "Falstaff shall die of a sweat, unless already a' be killed with your hard opinions; for Oldcastle died a martyr, and this is not the man." In 1599, another play, Sir John Oldcastle, presented Oldcastle in a more kindly light.

Bibliography

The record of Oldcastle's trial is printed in Fasciculi Zizaniorum (Rolls series) and in David Wilkins's Concilia, iii. 351–357. The chief contemporary notices of his later career are given in Gesta Henrici Quinti (Eng. Hist. Soc.) and in Walsingham's Historia Anglicana. There have been many lives of Oldcastle, mainly based on The Actes and Monuments of John Foxe, who in his turn followed the Briefe Chronycle of John Bale, first published in 1544.

For notes on Oldcastle's early career, consult James Hamilton Wylie, History of England under Henry IV. For literary history see the Introductions to Richard James's Iter Lancastrense (Chetham Society, 1845) and to Grosart's edition of the Poems of Richard James (1880). See also W. Barske, Oldcastle-Falstaff in der englischen Literatur bis zu Shakespeare (Palaestra, 1. Berlin, 1905).

Notes

- 1 2 Waugh 1905, p. 436.

- 1 2 3 Waugh 1905, p. 437.

- 1 2 Waugh 1905, p. 438.

- 1 2 Waugh 1905, p. 445.

- ↑ Riley 1868, p. 641.

- ↑ Seward, pp.42–45.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.- Cooper, Stephen (2010), The Real Falstaff, Sir John Fastolf and the Hundred Years War, Pen & Sword.

- Riley, Henry Thomas (1868), Memorials of London and London Life, a series of Extracts from the City Archives, 1276–1419.

- Desmond Sweard, Henry V as Warlord, London: Sidgwick & Jacskon, 1987.

- Waugh, WT (1905), "Sir John Oldcastle", The English Historical Review, 20 (79): 434–56, doi:10.1093/ehr/xx.lxxix.434.

External links

- The proclamation offering a reward for the capture of Sir John Oldcastle, UK: The National Archives.

"Oldcastle, John". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

"Oldcastle, John". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.