Joos van Cleve

Joos van Cleve (/ˈkleɪvə/;[1] also Joos van der Beke; c. 1485 – 1540/1541) was a painter active in Antwerp around 1511 to 1540. He is known for combining traditional Netherlandish painting techniques with influences of more contemporary Renaissance painting styles.[2]

An active member and co-deacon of the Guild of Saint Luke of Antwerp, he is known mostly for his religious works and portraits of royalty. As a skilled technician, his art shows sensitivity to color and a unique solidarity of figures.[3] He was one of the first to introduce broad landscapes in the backgrounds of his paintings, which would become a popular technique of sixteenth century northern Renaissance paintings.

He was the father of Cornelius or Cornelis van Cleve (1520-1567) who was also a painter and is believed to have suffered from a mental illness and was therefore referred to as 'Sotte Cleef' (mad Cleef).[4][5]

Life

Early life

Joos van Cleve was born around 1485. The birthplace of Joos van Cleve is not precisely known. In various Antwerp legal documents he is referred to as ‘Joos van der Beke alias van Cleve’. It is therefore likely that he came from the Lower Rhenish region or city named Kleve, from which his name is derived. It is assumed that he began his artistic training around 1505 in the workshop of Jan Joest, whom he assisted in the panel paintings of the high altar for the Nikolaikirche in Kalkar, Lower Rhine, Germany.[6]

Joos van Cleve is believed to have moved to Bruges between 1507 - 1511 since his painting style is similar to that of the painters of Bruges.[5] Later he moved to Antwerp, and in 1511 became a free master in the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke. He was co-deacon of the guild for several years around 1520, along with presenting pupils between 1516 and 1536.[4] It is possible he spent time in France at the court in 1529 or 1535. He may also have made a trip to Italy around this time and to London (England) around 1535-1536.[5]

Personal life

He had two children from his first marriage, a daughter and a son. His son Cornelis (1520) became a painter. Although the date of his death is unknown, Joos van Cleve drew up a will and testament on 10 November 1540, and his second wife was listed as a widow in April 1541.[4]

Work

Alias and identity

From the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries, the name of Joos van Cleve as an artist was lost. The paintings now attributed to Joos van Cleve were, at that time, known as the works of “the Master of the Death of the Virgin,” after the triptych currently in the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum (Cologne). In 1894 it was discovered that the monogram on the back of the triptych was that of Joos van der Beke, an alias of Joos van Cleve.[4]

Artistic influences

The influence of Kalkar and Bruges are seen in many of Joos van Cleve’s early works, such as Adam and Eve (1507). The Death of the Virgin (1520) shows the combined influence of several artists. It has the intense emotionality of Hugo van der Goes, and iconographic ideas of Jan van Eyck and Robert Campin. A strong influence of Italian art combined with Joos van Cleve’s own color and light sensitivity make his works especially unique. The “Antwerp Mannerist” style is identifiable in the Adoration of the Magi. It is thought that the “Antwerp Mannerists” were in turn influenced by Joos van Cleve.

Like Quentin Matsys, a fellow artist active in Antwerp, Joos van Cleve appropriated themes and techniques of Leonardo da Vinci. This is apparent in the use of sfumato in the Virgin and Chil. Multiple versions of a soft, sentimental Madonna and Child and the Holy Family were discovered, produced in his workshop.[4]

Royal portraits

Joos van Cleve’s skills as a portrait artist were highly regarded as demonstrated by a summons to the court of Francis I of France. There he painted the king (Philadelphia Museum of Art), the queen Eleanor of Austria (Kunsthistorisches Museum) and other members of the court.[4] His portrait of Henry VIII of England is of comparable size to that of Francis I (72.1 x 59.2 cm) and the compositions and costumes in both portraits are similar. Some historians have interpreted this as evidence that the portraits were pendants painted to commemorate the meeting of the two kings in Calais and Boulogne on 21 and 29 October 1532. Other historians have proposed the alternative view that van Cleve based the Henry VIII portrait on that of Francis I without meeting the English king. He may have hoped that this gesture might earn him English royal commissions in future.[7]

Virgin and child and Holy Family

Joos van Cleve produced many versions of the Virgin and Child, the Holy Family and the Virgin and Child with St Anne, which were very popular. In some instances the original has been lost, but the type can be recovered through the numerous replicas produced by his workshop and copyists. There exist very similar versions of the composition of the Virgin and Child, of which one is held at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest and another was sold at Sotheby's on 30 January 2014. It is full of charm and tenderness and was popular in his own time as well as with later collectors. The composition shows the Virgin with a brilliant red cloak, lined with fur and elaborately embroidered with pearls along the outside edge. The Virgin is seated in a loggia-like space with open windows through which a distant mountainous landscape is visible. She has her lips parted in a slight smile while she helps the Christ Child drink from a glass with red wine, a symbol of Christ's future suffering and blood and the Eucharist. Characteristic of Netherlandish painting of this period are the jewel-like colours and the details of the Virgin’s costume and brocade pillow in the foreground.[8]

The pose of the Holy Family in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (c. 1518–20) is quoted from Jan van Eyck's Lucca Madonna of c. 1435 (Städel, Frankfurt). The scene is placed in a domestic setting and the Virgin is only depicted at half-length. Another change in the composition is the addition of Joseph. The wine and fruits on the foreground are a reference to Christ's incarnation and future sacrifice. They also hint at the emerging genre of still-life painting in Flanders.[9]

Works (partial list)

In chronological order

- The Holy Family (1515), Akademie der bildenden Kunste, Vienna

- Saint Reinhold Altar (before 1516), National Museum, Warsaw

- Triptych. Centre: the Deposition from the Cross; Left wing: St John the Baptist with a Donor; Right wing: St Margaret of Antioch with a Donatrix (1518-1519), National Galleries Scotland, Edinburgh[10]

- Self-Portrait (1519), Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

- The Death of the Virgin (1520), Alte Pinakothek, Munich

- Man with the Rosary (1520), National Museum, Belgrade[11]

- Altarpiece of the Lamentation (1520–25), Musée du Louvre, Paris

- The Suicide of Lucretia (1520–25), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- Portrait of a Man and Woman (1520 and 1527), Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

- The Annunciation (1525), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- The Infants Christ and Saint John the Baptist Embracing (1525–30), Art Institute, Chicago

- Adoration of the Magi (1526–28), Gemaldegalerie, Dresden

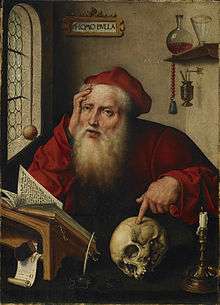

- Saint Jerome in his Study (1528), Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton

- Portrait of Eleonora, Queen of France (1530), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- Virgin and Child (1535), Landesmuseum, Oldenburg

- Madonna and Child against the renaissance background (c. 1535), Museum of King Jan III's Palace at Wilanów, Warsaw

Dates unknown

- Death of the Virgin, Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne

- The Holy Family, The Hermitage, St. Petersburg

- Mona Vanna, National Gallery, Prague

- Portrait of Agniete ven den Rijne, Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede

- Portrait of Anthonis van Hilten, Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede

- St. Anne with the Virgin and Child and St. Joachim, Musee Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels

- Virgin and Child, Szepmuveszeti Muzeum, Budapest

- Triptych of Saint Peter, Saint Paul and Saint Andrew, Museu de Arte Sacra do Funchal

References

- ↑ "Cleve". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ↑ "Rijksmuseum: Joos van Cleve".

- ↑ Hand, John Oliver (2005). Joos Van Cleve: The Complete Paintings. Yale University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-300-10578-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Campbell, Lorne (2000). The fifteenth century Netherlandish paintings : National Gallery catalogues (Repr. ed.). New Haven: Yale Univ. Press. ISBN 0-300-07701-7.

- 1 2 3 Joos van Cleve at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (Dutch)

- ↑ John Oliver Hand. "Cleve, van (i)." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 25 March 2015

- ↑ Joos van Cleve (active 1505/08-1540/41), Henry VIII at the Royal Collection

- ↑ Virgin and Child at Sotheby's

- ↑ The Holy Family in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ↑ Triptych. Centre: the Deposition from the Cross; Left wing: St John the Baptist with a Donor; Right wing: St Margaret of Antioch with a Donatrix (1518-1519), National Galleries Scotland, Edinburgh

- ↑ Man with the Rosary (1520), National Museum, Belgrade

External links

Media related to Joos van Cleve at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Joos van Cleve at Wikimedia Commons