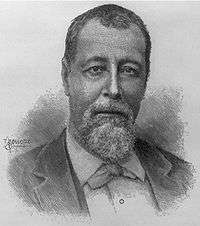

Justo Rufino Barrios

| His Excellency General of Division Justo Rufino Barrios | |

|---|---|

|

General Justo Rufino Barrios | |

| President of Guatemala | |

|

In office June 4, 1873 – April 2, 1885 | |

| Preceded by | Miguel García Granados |

| Succeeded by | Alejandro M. Sinibaldi |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

July 19, 1835 San Lorenzo, San Marcos |

| Died |

April 2, 1885 (aged 49) Chalchuapa, El Salvador |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse(s) | Francisca Aparicio |

| Residence | Guatemala City |

| Profession | Army General |

| Religion | Roman Catholic, then Positivism |

Justo Rufino Barrios (July 19, 1835, in San Lorenzo, San Marcos – April 2, 1885, in Chalchuapa, El Salvador) who was President of Guatemala was known for his liberal reforms and his attempts to reunite Central America.

Early life

Barrios was known from his youth for his intellect and energy, went to Guatemala City to study law, and became a lawyer in 1862.

Rise to power

In 1867, revolt broke out in western Guatemala, which many residents wished to return to its former status of an independent state as Los Altos. Barrios joined with the rebels in Quetzaltenango, and soon proved himself a capable military leader, and in time gained the rank of general in the rebel army.

In July 1871, Barrios, together with other generals and dissidents, issued the "Plan for the Fatherland" proposing to overthrow Guatemala's long entrenched Conservadora (conservative) administration; soon after, they succeeded in doing so, and General García Granados was declared president and Barrios commander of the armed forces. While Barrios was back in Quetzaltenago, García Granados was seen as weak by his own party members and was asked to call for elections, as the general consent was that Barrios would make a better president. Barrios was elected president in 1873.

Government

The Conservative government in Honduras gave military backing to a group of Guatemalan Conservatives wishing to take back the government, so Barrios declared war on the Honduran government. At the same time, Barrios, together with President Luis Bogran of Honduras, declared an intention to reunify the old United Provinces of Central America.

During his time in office, Barrios continued with the liberal reforms initiated by García Granados, but he was more aggressive implementing them. A summary of his reforms is:[1]

- Definitive separation between church and state: he expelled the regular clergy such as Morazán had done in 1829 and confiscated their properties.

Properties confiscated from the clergy by Barrios regime[2] Regular order Coat of arms Clergy type Confiscated properties Order of Preachers

Regular - Monasteries

- Large extensions of farm land

- Sugar mills

- Indian doctrines[lower-alpha 1]

Mercedarians

Regular - Monasteries

- Large extensions of farm land

- Sugar mills

- Indian doctrines

Society of Jesus

Regular The Jesuits had been expelled from the Spanish colonies back in 1765 and did not return to Guatemala until 1852. By 1871, they did not have major possessions. Recoletos

Regular - Monasterires

Conceptionists

Regular - Monasteries

- Large extensions of farm land

Archdiocese of Guatemala Secular School and Trentin Seminar of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción Congregation of the Oratory Secular - Church building and housing in Guatemala City were completely obliterated by presidential order.[3]

- Forbid mandatory tithing to weaken secular clergy members and the archbishop.

- Established civil marriage as the only official one in the country

- Secular cemeteries

- Civil records superseded religious ones

- Established secular education across the country

- Established free and mandatory elementary schools

- Closed the Pontifical University of San Carlos and in its place created the secular National University.[1]

Barrios had a National Congress totally pledge to his will, and therefore he was able to create a new constitution in 1879, which allowed him to be reelected as president for another six-year term.[1]

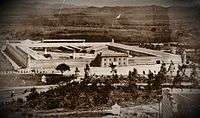

He also was intolerant with his political opponents, forcing a lot of them to flee the country and building the infamous Guatemalan Central penitentiary where he had numerous people incarcerated and tortured.[4]

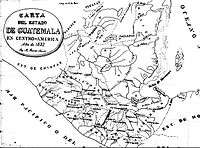

Guatemala administrative structure during his tenure

Appleton's guide for México and Guatemala from 1884,[5] shows the twenty departments in which Guatemala was divided during Barrios' time in office:[6]

| Departament | Area (square miles) | Population | Capital | Capital population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guatemala | 700 | 100,000 | Guatemala City | 50,000 |

| Sacatepéquez | 250 | 48,000 | Antigua Guatemala | 15,000 |

| Amatitlán | 200 | 38,000 | Amatitlán | 14,000 |

| Escuintla | 1,950 | 30,000 | Escuintla | 10,000 |

| Chimaltenango | 800 | 60,000 | Chimaltenango | 6,300 |

| Sololá | 700 | 80,000 | Sololá | 15,000 |

| Totonicapán | 700 | 114,000 | Totonicapan | 25,000 |

| Quiché | 1,300 | 75,000 | Santa Cruz del Quiché | 6,300 |

| Quezaltenango | 450 | 94,000 | Quezaltenango | 22,000 |

| Suchitepéquez | 2,500 | 69,000 | Suchitpéquez | 11,500 |

| Huehuetenango | 4,550 | 90,000 | Huehuetenango | 16,000 |

| San Márcos | 750 | 100,000 | San Márcos | 12,600 |

| Petén | 13,200 | 14,000 | Flores | 2,200 |

| Verapaz | 11,200 | 100,000 | Salamá | 8,000 |

| Izabal | 1,500 | 3,400 | Izabal | 750 |

| Chiquimula | 2,200 | 70,000 | Chiquimula | 12,000 |

| Zacapa | 4,400 | 28,000 | Zacapa | 4,000 |

| Jalapa | 450 | 8,600 | Jalapa | 4,000 |

| Jutiapa | 1,700 | 38,000 | Jutiapa | 7,000 |

| Santa Rosa | 1,100 | 38,500 | Cuajiniquilapa | 5,000 |

| Total | 50,600 | 1,198,500 |

Barrios oversaw substantial cleaning and rebuilding of Guatemala City, and set up a new and accountable police force. He brought the first telegraph lines and railroads to the republic. He established a system of public schools in the country.

Economy

Decree #177

Day Laborers regulations

(NOTE: Only main sections are presented)

- Employer obligations: employers are mandated to keep record of all accounts, where they will keep the debits and credits of each day laborer, making it known to the laborer every week by an accounting booklet.

- A day laborer can be contracted upon employer's needs, but it cannot go beyond four years. However, a day laborer cannot leave the employer's farm land until he has paid in full any debts he or she might have incurred at the time.

- When a person wishes for his or her farm a batch of day laborers, he or she must request it from the Political Chief of the Department he or she lives in, whose authority will designate which native town must provide such batch. In any case can be larger than 60 day laborers.

From: Martínez Peláez, S. La Patria del Criollo, intepretation essay of Gautemala Colonial reality México. 1990[7]

During Barrios' tenure, the "indian land" that the conservative regime of Rafael Carrera had so strongly defended was confiscated and distributed among those officers who had helped him during the Liberal Revolution in 1871.[7] Decree # 170 (a.k.a. Census redemption decree) made it easy to confiscate those lands in favor of the army officers and the German settlers in Verapaz as it allowed to publicly sell those common indian lots.[8] Therefore, the fundamental characteristic of the productive system during Barrios' regime was the accumulation of large extension of land among few owners[9] and a sort of "farmland servitude," based on the exploitation of the native day laborers.[8]

In order to make sure that there was a steady supply of day laborers for the coffee plantations, which required a lot of them, Barrios' government decreed the Day Laborer regulations, labor legislation that placed the entire native population at the disposition of the new and traditional Guatemalan landlords, except the regular clergy, who were eventually expelled form the country and saw their properties confiscated.[7] This decree set the following for the native Guatemalans:

- Were forced by law to work in farm lands when the owners of those required them, without any regard for where the native towns were located.

- Were under control of local authorities, who were in charge to make sure that day laborer batches were sent to all the farms that required them.

- Were subject to "habilitation:" a type of forced advanced pay, which buried the day laborer in debt and then made it legal for the landlords to keep them on their land for as long as they wanted.

- Created the day laborer booklet: a document that proved that a day laborer had no debts to his employer. Without this document, any day laborer was at the mercy of the local authorities and the landlords.[10]

Second term

In 1879, a constitution was ratified for Guatemala (the Republic's first as an independent nation, as the old Conservador regime had ruled by decree). In 1880, Barrios was reelected President for a six-year term. Barrios unsuccessfully attempted to get the United States of America to mediate the disputed boundary between Guatemala and Mexico.

Central America Union

Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras agreed to reform the Central American Union, but then Salvadoran President Rafael Zaldivar decided to withdraw from the union, and sent envoys to Mexico to join in an alliance to overthrow Barrios. Mexican President Porfirio Díaz feared Barrios' liberal reforms and the potential of a strong Central America as a neighbor if Barrios' plans bore fruit. Díaz sent Mexican troops to seize the disputed land of Soconusco.

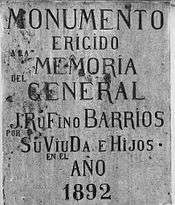

Death

Justo Rufino Barrios died during the Chalchuapa Battle in El Salvador, as did his son General Venancio Barrios on April 2, 1885. The official liberal version is that Barrios was killed in action, alongside officer Adolfo V. Hall. However, there are some versions insisting that a Guatemalan soldier missed a shot and killed president Barrios from behind[1] or that there might have been a murder plot.

Upon learning about his death, the Guatemalan Army panicked; officer José María Reyna Barrios, president Barrios' nephew, picked up the lifeless body of Venancio Barrios and organized the withdrawal of the Guatemalan battalions, while preparing the defense against a possible Salvadorian attack. Reyna Barrios, signing as Rosario Yerjabens,[lower-alpha 2] told the story of what he saw, which does not match the official account: "The general in Chief, Justo Rufino Barrios, decided, about 8 a.m., to personally command the attack on the northeast side of "Casa Blanca"; and in order to accomplish that, he sent the Jirón Brigade, whose soldiers were all Jalapas.[lower-alpha 3] These soldiers behaved in the most cowardly and disgraceful way. It is believed that they had been indoctrinated by some miserable traitor, one of those men without heart or conscience, one of those ungrateful people that was licking their benefactor's hand and abusing both his good heart and fortune. Unfortunately, a moment after the attack began, an enemy bullet wounded him mortally and he had to be taken off the battlefield. This sad occurrence was enough for some coward Jalapa soldiers who saw general Barrios dead, to leave their post and spread the sad news."[11]

On April 4, the defeated Guatemalan forces arrived to Guatemala City, where Reyna Barrios was promoted to general for his valiant battle services.

Today, his portrait is on the five quetzal bill in Guatemala, and the city and port of Puerto Barrios, capital of Izabal, bears his name.

See also

-

Guatemala portal

Guatemala portal -

Biography portal

Biography portal - Avenida Reforma

- History of Central America

- History of Guatemala

- Presidents of Guatemala

- Torre del Reformador

Notes and references

References

- 1 2 3 4 Barrientos 1948, p. 108.

- ↑ Castellanos Cambranes 1992.

- ↑ Ortiz 2007.

- ↑ De los Ríos 1948, p. 34.

- ↑ Conkling 1884, p. 334.

- ↑ Conkling 1884, p. 335.

- 1 2 3 Martínez Peláez 1990, p. 842.

- 1 2 Castellanos Cambranes 1992, p. 316.

- ↑ Mendizábal n.d.

- ↑ Martínez Peláez 1990, p. 854.

- ↑ Coronado Aguilar 1968, p. 15.

Bibliography

- Barrientos, Alfonso Enrique (1948). "Ramón Rosa y Guatemala" (PDF). Revista del archivo y biblioteca nacionales (in Spanish). Honduras. 27 (3-4).

- Castellanos Cambranes, Julio (1992). "5. Tendencias del desarrollo agrario en el siglo XIX y surgimiento de la propiedad capitalista de la tierra en Guatemala" (PDF). 500 años de lucha por la tierra. Estudios sobre propiedad rual y reforma agraria en Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala: FLACSO. 1.

- Conkling, Alfred R. (1884). Appleton's guide to Mexico, including a chapter on Guatemala, and a complete English-Spanish vocabulary. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- Coronado Aguilar, Manuel (1968). "Así murió el general J. Rufino Barrios". El Imparcial (in Spanish). Guatemala.

- De los Ríos, Efraín (1948). Ombres contra Hombres (in Spanish). México: Fondo de Cultura de la Universidad de México.

- Martínez Peláez, Severo (1990). La Patria del Criollo, Ensayo de interpretación de la realidad colonial guatemalteca (in Spanish). México: Ediciones en Marcha.

- Mendizábal, A.B. (n.d.). Estado y políticas de desarrollo agrario: la masacre campesina de Panzós (in Spanish). Guatemala.

- Ortiz, Oscar G. (2007). "Jesús de las Tres Potencias". Cuaresma y Semana Santa (in Spanish). Guatemala. Archived from the original on 22 February 2007. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

External links

-

Media related to Justo Rufino Barrios at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Justo Rufino Barrios at Wikimedia Commons - (Spanish) [Short biography and picture http://www.deguate.com/personajes/article_761.shtml]

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Miguel García Granados |

President of Guatemala 1873–1885 |

Succeeded by Alejandro M. Sinibaldi (acting) |