Kentucky gubernatorial election, 1899

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Kentucky gubernatorial election of 1899 was held on November 7, 1899, to choose the 33rd governor of Kentucky. The incumbent, Republican William O'Connell Bradley, was term-limited and unable to seek re-election.

After a contentious and chaotic nominating convention at the Music Hall in Louisville, the Democratic Party chose state Senator William Goebel as its nominee. A dissident faction of the party, styling themselves the "Honest Election Democrats", were angered by Goebel's political tactics at the Music Hall convention and later held their own nominating convention. They chose former governor John Y. Brown as their nominee. Republicans nominated state Attorney General William S. Taylor, although Governor Bradley favored another candidate and lent Taylor little support in the ensuing campaign. In the general election, Taylor won by a vote of 193,714 to 191,331. Brown garnered 12,040 votes, more than the difference between Taylor and Goebel. The election results were challenged on grounds of voter fraud, but surprisingly, the state Board of Elections, created by a law Goebel had sponsored and stocked with pro-Goebel commissioners, certified Taylor's victory.

An incensed Democratic majority in the Kentucky General Assembly created a committee to investigate the charges of voter fraud, even as armed citizens from heavily Republican eastern Kentucky poured into the state capital under auspices of keeping Democrats from stealing the election. Before the investigative committee could report, Goebel was shot by an unknown assassin while entering the state capitol on January 30, 1900. As Goebel lay in a nearby hotel being treated for his wounds, the committee issued its report recommending that the General Assembly invalidate enough votes to give the election to Goebel. The report was accepted, Taylor was deposed, and Goebel was sworn into office on January 31. He died three days later on February 2.

Lieutenant Governor J. C. W. Beckham ascended to the office of governor, and he and Taylor waged a protracted court battle over the governorship. Beckham won the case on appeal, and Taylor fled to Indiana to escape prosecution as an accomplice in Goebel's murder. A total of sixteen people were charged in connection with the assassination. Five went to trial; two of those were acquitted. Each of the remaining three were convicted in trials fraught with irregularities and were eventually pardoned by subsequent governors. The identity of Goebel's assassin remains a mystery.

Background

In the 1895 gubernatorial election, Kentucky elected its first-ever Republican governor, William O. Bradley. Bradley was able to capitalize both on divisions within the Democratic Party over the issue of Free Silver and on the presence of a strong third-party candidate, Populist Thomas S. Pettit, to secure victory in the general election by just under 9,000 votes. This election marked the beginning of nearly thirty years of true, two-party competition in Kentucky politics.[1]

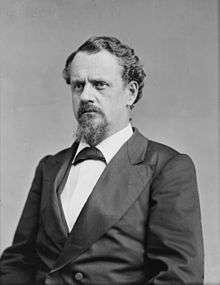

A powerful Democratic foe of Bradley had begun his rise to power in the Kentucky Senate. Kenton County's William Goebel became the leader of a new group of young Democrats who were seen as enemies of large corporations, particularly the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, and friends of the working man. Goebel was known as aloof and calculating. Unmarried and with few close friends of either gender, he was singularly driven by political power.[2]

Goebel was chosen president pro tem of the Senate for the 1898 legislative session. On February 1, 1898, he sponsored a measure later called the Goebel Election Law.[3] The law created a Board of Election Commissioners, appointed by the General Assembly, who were responsible for choosing election commissioners in all of Kentucky's counties and were empowered to decide disputed elections.[3] Because the General Assembly was heavily Democratic, the law was attacked as blatantly partisan and self-serving to Goebel; it was opposed even by some Democrats.[4] Nevertheless, Goebel was able to hold enough members of his party together to override Governor Bradley's veto, making the bill law.[4] As leader of the party, Goebel essentially hand-picked the members of the Election Commission.[5] He chose three staunch Democrats—W. S. Pryor, former chief justice of the Kentucky Court of Appeals; W. T. Ellis, former U. S. Representative from Daviess County; and C. B. Poyntz, former head of the state railroad commission.[5] Republicans organized a test case against the law, but the Court of Appeals found it constitutional.[6]

Democratic nominating convention

Three Democratic candidates had announced intentions to run for governor in 1899—Goebel, former Kentucky Attorney General P. Wat Hardin, and former congressman William J. Stone.[7] Hardin, a native of Mercer County, had the backing of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad.[7] Lyon County's Stone had the backing of the state's agricultural interests.[7] Goebel generally had the backing of urban voters.[7] Going into the party's nominating convention, Hardin was the favorite to win the nomination.[7] Knowing that combining forces was the only way to prevent Hardin's nomination, representatives of Goebel and Stone met on June 19, 1899, to work out a deal.[8] According to Urey Woodson, a Goebel representative at the meeting, the two sides signed an agreement whereby half of the Louisville delegation, which was committed to Goebel, would vote for Stone.[7] Both men agreed that, should one of them be defeated or withdraw from the race, they would encourage their delegates to vote for the other rather than support Hardin.[7]

The Democratic nominating convention began on June 20, at the Music Hall on Market Street in Louisville.[7] The first order of business was to nominate a convention chairman. Ollie M. James, a supporter of Stone, nominated Judge David Redwine.[8] When Woodson seconded the nomination, the deal between Stone and Goebel became apparent to all.[8] Hardin supporters nominated William H. Sweeney, but the Stone-Goebel alliance elected Redwine.[9] The membership of several county delegations was challenged; these cases would be decided by the credentials committee.[9] This committee was also stacked against Hardin; his supporters made up just four of the thirteen members.[9] Prolonged deliberations by the credentials committee caused the delegates to become restless, and hundreds of people—both delegates and non-delegates—entered the Music Hall attempting to disrupt the convention.[7] When Redwine summoned Louisville city police to the hall to maintain order, Hardin supporters accused him of using intimidation tactics.[10] The credentials committee finally issued its report on June 23.[10] Of the twenty-eight cases where delegates were contested, twenty-six of them were decided in favor of Goebel or Stone supporters.[10]

Formal nominations began the following day.[10] Hardin felt as though he had been cheated and withdrew his candidacy, although some loyal delegates continued to vote for him.[11] Delegate John Stockdale Rhea nominated Stone.[10] Stone believed that his agreement with Goebel meant, with Hardin's withdrawal, Goebel would instruct his delegates to vote for Stone, maintaining a unified party.[10] That understanding vanished when another delegate nominated Goebel.[10] Stone was further incensed when all of the Louisville delegation voted for Goebel instead of being split between Stone and Goebel, as the two men had previously agreed.[10] In retaliation, some Stone supporters began to back Hardin.[10] Seeing the breakdown of the Stone-Goebel alliance, Hardin reversed his withdrawal.[12] After numerous ballots, the convention was deadlocked on the night of June 24 with each candidate receiving about one-third of the votes.[13] No deliberations were held on Sunday, June 25, and when the delegates reconvened on Monday, June 26, the hall was filled with police per Redwine's request.[10] Rhea requested that the police be removed to prevent intimidation, but Redwine ruled the motion out of order.[10] Another delegate appealed Redwine's decision, and, in violation of parliamentary rule, Redwine ruled the appeal out of order.[12] Angered by Redwine's obviously biased rulings, delegates for Stone and Hardin then began trying to disrupt the convention by blowing horns, singing, yelling, and standing on chairs.[10] Although voting was attempted, many delegates abstained because they were unable to hear and understand what was going on.[10] When the voting—such as it was—ended, the chair announced that Goebel had a majority of the votes cast, but Goebel sent word to Redwine that he would only accept the nomination if he received an absolute majority of the delegates.[14] Further attempts to vote were likewise disrupted, and the meeting adjourned for the day.[10]

On the morning of June 27, the hall was orderly.[10] Stone and Hardin both called for the convention to adjourn sine die.[14] Again, Redwine ruled this motion and the subsequent appeal of his decision out of order.[14] Leaders for Stone and Hardin announced they would not disrupt the proceedings as they had the previous day and that they would abide by the convention's decision.[14] As voting proceeded, Stone and Hardin unsuccessfully tried to form an alliance against Goebel, and the balloting was deadlocked for twenty-four consecutive ballots.[10] The delegates agreed to drop the third-place candidate on the next ballot; that turned out to be Stone.[10] The votes of the urban centers, previously divided between Stone and Goebel, now went entirely to Goebel, while the rural western counties that had supported Stone went to Hardin.[15] The vote remained close, but as the alphabetical roll call proceeded, Goebel secured the votes of Stone's Union County delegation, giving him the nomination.[10] Following the vote, Hardin and Stone leaders pledged their support to Goebel, though some did so in qualified terms.[15] For lieutenant governor, the Democrats nominated J. C. W. Beckham who, at age 29, was not yet legally old enough to assume the governorship if called on to do so.[15] Goebel questioned the selection of Beckham because Beckham's native Nelson County had voted for Hardin and was largely controlled by political boss Ben Johnson, but Goebel's allies convinced him that Beckham would be loyal to his program.[15] Among the other nominees was ex-Confederate soldier Robert J. Breckinridge, Jr., for attorney general.[16] This nomination helped placate the numerous ex-Confederates in the party, since Goebel's father had fought for the Union.[16] It was not enough, however, to persuade Breckinridge's brother, former congressman W. C. P. Breckinridge, to support the ticket.[16]

Republican nominating convention

Potential Republican gubernatorial candidates were initially few.[17] Some saw Kentucky's 18,000-vote plurality for William Jennings Bryan in the 1896 presidential election as a sure sign that the state would vote Democratic in 1899.[17] Others were not interested in being on the defense against the inevitable Democratic attacks on the Bradley administration.[17] Still others were intimidated by the prospect of being defeated by the machinery of the Goebel Election Law.[17] Party leaders were encouraged, however, by the deep Democratic divisions at the Music Hall Convention.[18] Sitting attorney general William S. Taylor was the first to announce his candidacy and soon secured the support of Republican senator William Deboe.[17][18] Later candidates included Hopkins County judge Clifton J. Pratt and sitting state Auditor Sam H. Stone.[17] The former was the choice of Governor Bradley, while the latter was supported by Lexington Herald editor Sam J. Roberts.[18] Taylor, like Goebel, was a skilled political organizer.[18] He was able to create a strong political machine amongst the county delegations and seemed the favorite to win the nomination.[18]

The Republican nominating convention convened on July 12 in Lexington, Kentucky.[19] Angry that his party had not more seriously considered his candidate, Governor Bradley did not attend.[18] Black leaders in the party threatened to follow Bradley and organize their own nominating convention, as they believed Taylor represented the "lily-white" branch of the party.[18] Taylor attempted to hold the party together by making one of the black leaders permanent secretary of the convention and promising to appoint other black leaders to his cabinet if elected.[18] He also tried to bring Bradley back to the convention by promising to nominate Bradley's nephew, Edwin P. Morrow, for secretary of state.[18] Bradley refused the offer.[18] In the face of Taylor's superior organization, Auditor Stone announced that he desired to see a united party and moved that Taylor be nominated unanimously; Judge Pratt seconded the motion.[20] Other notable nominations were John Marshall for lieutenant governor, Caleb Powers for secretary of state, and Judge Pratt for attorney general.[21]

"Honest Election Democrats"

Some Democrats remained unsatisfied with the outcome of the Music Hall Convention. After a period of silence, candidate William Stone publicly detailed the arrangement he believed he had with Goebel and how Goebel had broken it. Although Goebel's allies attempted to defend him against the charges, Stone's story was soon corroborated by former congressman W. C. Owens. Owens called on Democrats to vote for the Republican candidate, and to do so in such large numbers that no amount of political wrangling by Goebel could give him the governorship.[22]

A group of Louisville Democrats, supporters of U. S. Senator Jo Blackburn, made the first formal calls for a new convention. A short time after, a large meeting at Mount Sterling gave the movement a definite form. They called for a meeting in Lexington on August 2 to organize the details of a new convention. At subsequent mass meetings, it was announced that former governor John Y. Brown would accept the nomination of a second convention, should one be held. As Brown had been thought to be a supporter of Goebel, this announcement caused no small stir among Democrats. Representatives of sixty counties attended the August 2 meeting in Lexington. Resolutions endorsing the Democratic platform from the 1896 Democratic National Convention and the candidacy of William Jennings Bryan in 1900 were adopted. Then, ex-governor Brown addressed the crowd. Finally, the representatives agreed to a nominating convention to be held on August 16.[23]

Representatives from 108 of Kentucky's 120 counties attended the convention.[24] Among the attendees were the editors of the Lexington Herald, Louisville Evening Post, and Louisville Dispatch, former congressman Owens, former Speaker of the Kentucky House of Representatives Harvey Myers, Jr., and political bosses William Mackoy, John Whallen, and Theodore Hallam.[25] The convention nominated an entire slate of candidates for state office, with former governor Brown at the head.[25] They also put forward a platform condemning the Music Hall Convention, the Goebel Election Law, and the presidential administration of William McKinley.[26]

Campaign

Goebel's campaign staff included Senator Jo Blackburn, former governor James B. McCreary, and political boss Percy Haly. Goebel opened his campaign on August 12 in Mayfield, a city in the heavily Democratic Jackson Purchase region of the state. He attacked the Louisville and Nashville Railroad and charged that wealthy corporate interests from outside the state were attempting to influence the choice of Kentucky's governor.[27]

Taylor opened his campaign on August 22 in London, a Republican stronghold in eastern Kentucky.[28][29] Among his supporters were Senator Deboe, Congressman Samuel Pugh, Caleb Powers, and former Republican gubernatorial candidate Thomas Z. Morrow (who was also the brother-in-law of Governor Bradley).[29][30] Taylor stressed the economic prosperity brought about during the McKinley administration.[30] He reminded the crowd that the Republicans had not supported the enslavement of blacks and stated they would not now support what he called the "political enslavement" that would result from electing Goebel.[30]

Brown opened his campaign in Bowling Green on August 26.[31] Because of his age and ill health, he made no more than one speech per week.[32] Nevertheless, he toured the Commonwealth, questioning the sincerity of Goebel's Free Silver views.[30] He continued to attack the Music Hall Convention, asking whether past great Democrats such as John C. Breckinridge and Lazarus W. Powell would have supported the events that took place there.[30] He also derided the Goebel Election Law as creating an oligarchy.[30] Brown's limited appearances were supplemented by speeches from his supporters.[32]

Although ex-Confederates were generally a safe voting bloc for Democrats, Goebel could not heavily rely on them because of his father's ties to the Union. Also, in 1895, Goebel had killed John Sanford, an ex-Confederate, in a duel stemming from a personal dispute between the two men. This made him particularly odious to Brown supporter Theodore Hallum, a friend of Sanford's, who said of Goebel at a campaign rally in Bowling Green "[W]hen the Democratic Party of Kentucky, in convention assembled, sees fit in its wisdom to nominate a yellow dog for the governorship of this great state, I will support him — but lower than that you shall not drag me."[33] Goebel tried to mitigate his lukewarm support from ex-Confederates by courting the black vote, long given to the Republicans, though he had to do so carefully to avoid further alienating his own party base. Unlike other Democrats, Goebel had not voted on the Separate Coach Bill, a law that required blacks and whites to use segregated railroad facilities. Most blacks opposed the bill, and Goebel tried to remain silent on the issue, but when pressed, he admitted in a campaign event in Cloverport that he supported the bill and would oppose its repeal. Likewise, Taylor had tried to dodge the issue of the Separate Coach Bill to avoid upsetting the "lily white" branch of his party, but a week after Goebel took a position in favor of the bill, Taylor came out against it. This marked a turning point in the campaign, as blacks, at first cool toward Taylor, now actively supported him.[34]

The dying Populist Party had also nominated a full slate of candidates for state offices, eroding some of Goebel's populist base. Although the Populist Party platform was similar to Goebel's, it also explicitly condemned the Goebel Election Law. Thomas Pettit, the Populist candidate from the 1895 gubernatorial election, campaigned for Goebel, but many of the other leaders in the party did not. With his support slipping on every side, Goebel appealed to William Jennings Bryan to come to the state and campaign for him. Known as "the Great Commoner", Bryan was immensely popular with Kentuckians, particularly Democrats and Populists. After refusing initial requests, Bryan finally came to the state and, in three days, crisscrossed the state with Goebel to stir up support. Bryan's visit helped solidify Democrats behind Goebel and took significant support from the Brown ticket.[35]

No sooner had Bryan left the state than Governor Bradley reversed course and began stumping for Taylor. Though he insisted he only wanted to defend his administration from Democratic attacks, Louisville Courier-Journal editor Henry Watterson suggested that Bradley was seeking to enlist Taylor's support for his anticipated senatorial bid. Bradley kicked off his tour of the state in Louisville, charging that Democrats had to import an orator for their candidate because all of the state's best men had deserted him. As evidence, he cited Goebel's lack of support from Democrat John G. Carlisle, his former ally, as well as Senator William Lindsay, W. C. P. Breckinridge, John Y. Brown, Theodore Hallum, W. C. Owens, Wat Hardin, and William Stone. He also encouraged blacks not to desert the Republican Party. He contrasted his appointments of blacks to his cabinet with the Democrats' support of the Separate Coach Bill. Bradley and Republican leader (and later governor) Augustus E. Willson toured the state on behalf of the Republican ticket, often drawing crowds larger than those assembled for Taylor.[36]

In the final two weeks of the campaign, Brown was injured in an accident and became a wheelchair user. This was a severe blow to an already faltering campaign, and it became clear that the race would primarily be between Goebel and Taylor. Both men spent the last days of the campaign in Louisville, knowing that, with its sizable population, it would be key to the election. Goebel continued his attack on the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, supporting striking laborers from the railroad and charging that the Republican party was controlled by trusts. Both Republicans and Democrats warned of the possibility that election fraud and violence would be perpetrated by the other side. Louisville mayor Charles P. Weaver, a Goebel Democrat, added 500 recruits to the city's police force just before the election, leading to charges that voter intimidation would occur in that city. Governor Bradley countered by ordering the state militia to be ready to quell any disturbances across the state. On election day, the headline of the Courier-Journal proclaimed "BAYONET Rule".[37]

Election and aftermath

For all the claims about the potential for violence, election day, November 7, remained mostly calm across the state.[38] Fewer than a dozen people were arrested statewide.[38] Voting returns were slow, and on election night, the race was still too close to call.[4] When the official tally was announced, Taylor had won by a vote of 193,714 to 191,331.[4] Brown had garnered 12,040 votes, and Populist candidate Blair had captured 2,936.[4] Had Goebel been able to win the votes that went to either of the third party candidates, he could have saved the election for the Democrats.[4] Charges of fraud began even before the official returns were announced.[39] In Nelson County, 1,200 ballots listed the Republican candidate as "W. P. Taylor" instead of "W. S. Taylor"; Democrats claimed these votes should be invalidated.[39] In Knox and Johnson counties, voters complained of "thin tissue ballots" that allowed the voter's choices to be seen through them.[39] One Democratic political boss even called for the entire Louisville vote to be invalidated because the state militia had intimidated voters there.[39] (Taylor had won by about 3,000 votes in Louisville.)[39]

Republicans gained an early victory when the Court of Appeals ruled that the Nelson County vote should stand.[40] The final result of the election, however, would be decided by the Board of Elections, created by the Goebel Election Law.[39] Newspapers across the state, both Democratic and Republican, called for the board's decision to be accepted as final.[39] Tensions grew as the date for the board's hearings drew near, and small bands of armed men from heavily Republican eastern Kentucky began to arrive in Frankfort, the state capital.[40] Just before the board's decision was announced, the number of armed mountain men was estimated at 500.[40] Although the board was thought to be controlled by Goebel, it rendered a surprise 2–1 decision to let the announced vote tally stand.[41] The board's majority opinion claimed that they did not have any judicial power and were thus unable to hear proof or swear witnesses.[42] Taylor was inaugurated on December 12, 1899.[41] Democrats were outraged; party leaders met on December 14 and called on Goebel and Beckham to contest the election.[42] Goebel had been inclined to let the result stand and seek a seat in the U. S. Senate in 1901, but he heeded the wishes of his party's leaders and contested the board's decision.[42]

Allie Young, chairman of the state Democratic Party, called a caucus of the Democratic members of the General Assembly to be held on January 1, 1900. As a result of the caucus, J. C. S. Blackburn was nominated for a seat in the U. S. Senate, Goebel was nominated as president pro tem of the Kentucky Senate, and South Trimble was nominated as speaker of the House. When the General Assembly convened, each Democratic nominee was elected, the party possessing heavy majorities in both houses. Lieutenant Governor Marshall presented a list of committees to the Senate, but that body voted 19–17 to set aside this list and approve a list provided by Goebel instead. Similarly, in the House, the list of committees presented by Speaker Trimble and approved by that body enumerated forty committees, none of them with a Republican majority.[43]

Goebel's and Beckham's challenges to the election results were received by the General Assembly on January 2.[44] The following day, the Assembly appointed a contest committee to investigate the allegations contained in the challenges, voter fraud and illegal military intimidation of voters among them.[45] The members of the committee were drawn at random, although the drawing was likely rigged—only one Republican joined ten Democrats on the committee.[45] (Chance dictated that the committee should have contained four or five Republicans.)[46] The joint committee on the rules recommended that the contest committee report at the pleasure of the General Assembly, that debate was limited once the findings were presented, and that the report be voted on in a joint session of the Assembly.[47] The rules further provided that the speaker of the House would preside over this joint session instead of the lieutenant governor, as was customary.[47] The Republican minority fought these provisions, but the Democratic majority passed them over their opposition.[47]

Goebel's assassination

Republicans around the state expected the committee to recommend disqualification of enough ballots to make Goebel governor.[45] Additional armed men from eastern Kentucky filled the capital.[48] Taylor, recognizing that the slightest incident could lead to violence, ordered the men home, and many of them complied.[48] Still, two or three hundred remained, awaiting the election committee's findings.[45] Others remained as witnesses set to testify before the contest committee.[49] Some of these Republican witnesses were arrested by local police, who were mostly Goebel partisans.[49] Governor Taylor issued pardons for some of them, citing their claims that the police robbed them upon their arrest.[49] To avoid arrest for carrying a concealed weapon, many of the Republican partisans began wearing their guns openly, adding to the tensions in the city, but effectively reducing the number of arrests by local police.[50]

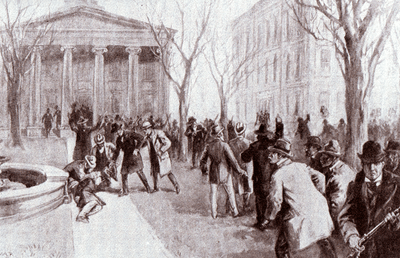

On the morning of January 30, as Goebel and two friends walked toward the capitol building, a shot rang out, and Goebel fell wounded.[51] He was taken to a nearby hotel to be treated for his wounds.[52] Soldiers filled the streets and blocked entrance to the capitol.[53] Defiantly, the contest committee met in Frankfort's city hall.[53] By a strictly party-line vote, they adopted a majority report that claimed Goebel and Beckham had received the most legitimate votes and should be installed in their respective offices.[53]

A little over an hour after the committee's meeting, Governor Taylor declared a state of insurrection and called out the state militia. He called the legislature into special session, not in Frankfort, but in heavily Republican London, which he insisted was a safer location. Defiant Democratic legislators refused to heed the call to London, but when they attempted to convene first in the state capitol and later in other public locations in Frankfort, they found the doors barred by armed citizens. On January 31, 1900, they convened secretly in a Frankfort hotel, with no Republicans present, and voted to certify the findings of the contest committee, invalidating enough votes to make Goebel governor. Goebel was sworn in, and immediately ordered the state militia to stand down. He also ordered the General Assembly to reconvene in Frankfort. The Republican militia refused to disband, and a rival Democratic militia formed across the lawn of the state capitol. Civil war seemed possible.[52]

Taylor apprised President McKinley of the situation in Kentucky. He stopped short of asking for intervention by federal troops, and McKinley assured a delegation of Kentucky's federal legislators that such intervention would occur only as a last resort. Republican legislators made preparations to heed Taylor's call to convene in London on February 5. Meanwhile, in order to resolve any doubts about the legitimacy of their earlier meeting, Democratic legislators met at the state house—no longer being denied entrance by the state militia—and again voted to adopt the majority report declaring Goebel and Beckham the winners of the election. Both men again took the oath of office.[54]

As a test to see if his gubernatorial authority was still recognized, Taylor issued a pardon for a man convicted of manslaughter in Knott County. The pardon was signed by the proper county officials, but officers at the penitentiary refused to release the man. It was feared that Taylor would dispatch the state militia to remove the prisoner, but no further attempts were made to secure his release. Continuing to live under heavy guard in his executive office, Taylor was criticized for not having offered a reward for the capture of Goebel's unknown assailant. Responding that he was not authorized to make an offer in the absence of a request to do so by the officials in Franklin County, he offered a $500 reward from his own money.[55]

Goebel died of his wounds on February 3.[52] He remains the only American governor ever assassinated while in office.[52] With Goebel, the most controversial figure in the election, dead, tensions began to ease somewhat.[56] Leaders from both sides drafted an agreement whereby Taylor and Lieutenant Governor Marshall would step down from their respective offices; in exchange, they would receive immunity from prosecution in any actions they may have taken with regard to Goebel's assassination.[57] The state militia would withdraw from Frankfort, and the Goebel Election Law would be repealed and replaced with a fairer law.[57] Despite the agreement of his allies, Taylor refused to sign the agreement.[57] He did, however, lift the ban on the General Assembly meeting in Frankfort.[57]

Legal challenges

When the legislature convened on February 19, two sets of officers attempted to preside.[57] Marshall and Goebel's lieutenant governor, J. C. W. Beckham, both claimed the right to preside over the state senate.[57] Taylor sued to prevent Beckham from exercising any authority in the senate; Beckham counter-sued for possession of the capitol and executive building.[57] The cases were consolidated, and both Republicans and Democrats agreed to let the courts decide the election.[56][57] On March 10, a circuit court found in favor of Beckham and the Democrats.[57] By a 6–1 vote, the Kentucky Court of Appeals, the state's court of last resort at the time, upheld the circuit court's decision on April 6, legally unseating Taylor and Marshall.[58][59] The case of Taylor v. Beckham[60] was eventually appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States, but the court refused to intervene in the case because it found that there were no federal questions involved.[56] The lone justice dissenting from that opinion was Kentuckian John Marshall Harlan.[56]

Sixteen indictments were returned in connection with Goebel's assassination, including one against deposed governor Taylor.[41] In May 1900, Taylor fled to Indianapolis, Indiana, and the governor, James A. Mount refused to extradite him for trial.[58] Three others charged in the assassination turned state's evidence.[41] Only five of the sixteen went to trial; two of those were acquitted.[41] Three men were eventually convicted for playing roles in Goebel's assassination.[56] Taylor's secretary of state, Caleb Powers, was accused of being the mastermind behind the assassination.[56] Henry Youtsey, a clerk from Northern Kentucky, was said to have aided the assassin.[56] James B. Howard, a participant in a bloody feud in Clay County was charged with being the actual assassin.[56]

According to the prosecution's theory, the assassin shot Goebel from the secretary of state's office on the first floor of a building next to the state capitol.[41] However, much of the testimony against the accused men was conflicting, and some of it was later proven to be perjured.[41] Most of the state's judges were Democratic supporters of Goebel and juries were packed with partisan Democrats.[56] The appellate courts, however, were largely Republican, and the convictions returned by the lower courts were often overturned, with the cases being remanded for new trials.[41] Howard was tried and convicted in September 1900, January 1902, and April 1903; his final appeal failed, and he was sentenced to life in prison.[41] Powers was also convicted three times—in July 1900, October 1901, and August 1903; a fourth trial in November 1907 ended in a hung jury.[41] In 1908, Powers and Howard were pardoned by Republican governor Augustus E. Willson.[56] Months later, Willson also issued pardons for former governor Taylor and several others still under indictment.[41] Despite the pardon, Taylor seldom returned to Kentucky; he became an insurance executive in Indiana and died there in 1928.[58] Youtsey, the only defendant not to appeal his sentence, was paroled in 1916 and pardoned in 1919 by Democratic governor James D. Black.[56]

See also

- Brooks–Baxter War — an armed conflict resulting from the 1872 Arkansas gubernatorial election

Notes

- ↑ Harrison in A New History of Kentucky, pp. 267–268

- ↑ Harrison in A New History of Kentucky, pp. 268–269

- 1 2 Kleber, "Goebel Election Law", p. 378

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Harrison in A New History of Kentucky, p. 270

- 1 2 Hughes, p. 7

- ↑ Hughes, p. 8

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Kleber, "Music Hall Convention", p. 666

- 1 2 3 Tapp, p. 418

- 1 2 3 Tapp, p. 419

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Kleber, "Music Hall Convention", p. 667

- ↑ Tapp, p. 420

- 1 2 Tapp, p. 421

- ↑ Hughes, p. 32

- 1 2 3 4 Tapp, p. 422

- 1 2 3 4 Tapp, p. 423

- 1 2 3 Tapp, p. 424

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hughes, p. 50

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Tapp, p. 425

- ↑ Hughes, p. 52

- ↑ Hughes, p. 53

- ↑ Tapp, p. 426

- ↑ Hughes, pp. 44, 46

- ↑ Hughes, pp. 46–47, 60

- ↑ Hughes, p. 68

- 1 2 Tapp, p. 428

- ↑ Hughes, p. 69

- ↑ Tapp, pp. 429–430

- ↑ Tapp, p. 430

- 1 2 Hughes, p. 72

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tapp, p. 432

- ↑ Hughes, p. 70

- 1 2 Hughes, p. 77

- ↑ Tapp, p. 433

- ↑ Tapp, pp. 434–436

- ↑ Tapp, pp. 436–437

- ↑ Tapp, pp. 437, 439

- ↑ Tapp, pp. 439–440

- 1 2 Tapp, p. 440

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tapp, p. 441

- 1 2 3 Tapp, p. 443

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Klotter, "Goebel Assassination", p. 377

- 1 2 3 Tapp, p. 444

- ↑ Hughes, pp. 157, 167, 174

- ↑ Hughes, p. 167

- 1 2 3 4 Harrison in A New History of Kentucky, p. 271

- ↑ Tapp, p. 445

- 1 2 3 Hughes, p. 174

- 1 2 Tapp, p. 446

- 1 2 3 Hughes, p. 188

- ↑ Hughes, p. 189

- ↑ Harrison in A New History of Kentucky, pp. 271–272

- 1 2 3 4 Harrison in A New History of Kentucky, p. 272

- 1 2 3 Tapp, p. 449

- ↑ Hughes, pp. 233, 235, 239

- ↑ Hughes, pp. 233, 236

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Harrison in A New History of Kentucky, p. 273

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Tapp, p. 451

- 1 2 3 Harrison, "Taylor, William Sylvester", p. 870

- ↑ Tapp, p. 453

- ↑ Taylor v. Beckham, 178 U.S. 610 (1900).

References

- Harrison, Lowell H. (1992). "Taylor, William Sylvester". In Kleber, John E. The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0.

- Harrison, Lowell H.; James C. Klotter (1997). A New History of Kentucky. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2008-X.

- Hughes, Robert Elkin; Frederick William Schaefer; Eustace Leroy Williams (1900). That Kentucky campaign: or, The law, the ballot and the people in the Goebel-Taylor contest. Cincinnati: R. Clarke Company.

- Kleber, John E. (1992). "Goebel Election Law". In Kleber, John E. The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0.

- Kleber, John E. (1992). "Music Hall Convention". In Kleber, John E. The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0.

- Klotter, James C. (1992). "Goebel Assassination". In Kleber, John E. The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0.

- Tapp, Hambleton; James C. Klotter (1977). Kentucky: decades of discord, 1865–1900. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-916968-05-7.

Further reading

- Klotter, James C. (1977). William Goebel: The Politics of Wrath. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-0240-5.

- McQueen, Keven (2001). "William Goebel: Assassinated Governor". Offbeat Kentuckians: Legends to Lunatics. Ill. by Kyle McQueen. Kuttawa, Kentucky: McClanahan Publishing House. ISBN 0-913383-80-5.

- Woodson, Urey (1939). The First New Dealer, William Goebel: His origin, ambitions, achievements, his assassination, loss to the state and nation; the story of a great crime. Louisville, Kentucky: The Standard Press.