Kingdom of Naples

| Kingdom of Sicily (Naples) Regnum Neapolitanum (Latin) Regno di Napoli (Italian) | ||||||

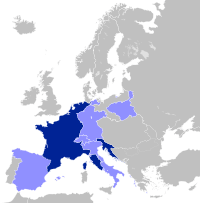

| Sovereign State under several branches of the Capetian Anjous (1282-1442) Part of the Crown of Aragon (1442-1458) Sovereign State under a cadet branch of the Aragonese House of Trastámara (1458-1501) Personal union of the Kingdom of France (1501-1504) Part of the Spanish Empire (1504–1714) Part of the Habsburg Empire (1714–1735) Sovereign State under a branch of the Bourbons (1735–1806) & (1815–1816) Client state of the French Empire (1806–1815) | ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

| Capital | Naples | |||||

| Government | Feudal absolute monarchy | |||||

| King | ||||||

| • | 1282–1285 | Charles I (first) | ||||

| • | 1806–1808 | Joseph I (last) | ||||

| History | ||||||

| • | Sicilian Vespers | 1282 | ||||

| • | Peace of Caltabellotta | 31 August 1302 | ||||

| • | Treaty of Rastatt | 7 March 1714 | ||||

| • | Battle of Campo Tenese | 10 March 1806 | ||||

| • | Two Sicilies established | 1808 | ||||

| Today part of | | |||||

The Kingdom of Naples (Neapolitan: Regno 'e Napule, Italian: Regno di Napoli), comprising the southern part of the Italian Peninsula, was the remainder of the old Kingdom of Sicily after the secession of the island of Sicily as a result of the Vespers of 1282.[1] It continued to be officially known as the Kingdom of Sicily, although it no longer included the island of Sicily. For much of its existence, the realm was contested between French and Spanish dynasties. In 1816, it was reunified with the island kingdom of Sicily once again to form the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

Angevin Kingdom of Naples

Following the rebellion in 1282, King Charles I of Sicily (Charles of Anjou) was forced to leave the island of Sicily by Peter III of Aragon's troops. Charles, however, maintained his possessions on the mainland, customarily known as the "Kingdom of Naples", after its capital city.

Charles and his Angevin successors maintained a claim to Sicily, warring against the Aragonese until 1373, when Queen Joan I of Naples formally renounced the claim by the Treaty of Villeneuve. Joan's reign was contested by Louis the Great, the Angevin King of Hungary, who captured the kingdom several times (1348–1352).

Queen Joan I also played a part in the ultimate demise of the first Kingdom of Naples. As she was childless, she adopted Louis I, Duke of Anjou, as her heir, in spite of the claims of her cousin, the Prince of Durazzo, effectively setting up a junior Angevin line in competition with the senior line. This led to Joan I's murder at the hands of the Prince of Durazzo in 1382, and his seizing the throne as Charles III of Naples.

The two competing Angevin lines contested each other for the possession of the Kingdom of Naples over the following decades. Charles III's daughter Joan II (r. 1414–1435) adopted Alfonso V of Aragon (whom she later repudiated) and Louis III of Anjou as heirs alternately, finally settling succession on Louis' brother René of Anjou of the junior Angevin line, and he succeeded her in 1435.

René of Anjou temporarily united the claims of junior and senior Angevin lines. In 1442, however, Alfonso V conquered the Kingdom of Naples and unified Sicily and Naples once again as dependencies of Aragon. At his death in 1458, the kingdom was again separated and Naples was inherited by Ferrante, Alfonso's illegitimate son.

Catalan Kingdom of Naples

When Ferrante died in 1494, Charles VIII of France invaded Italy, using as a pretext the Angevin claim to the throne of Naples, which his father had inherited on the death of King René's nephew in 1481. This began the Italian Wars.

Charles VIII expelled Alfonso II of Naples from Naples in 1495, but was soon forced to withdraw due to the support of Ferdinand II of Aragon for his cousin, Alfonso II's son Ferrantino. Ferrantino was restored to the throne, but died in 1496, and was succeeded by his uncle, Frederick IV.

Charles VIII's successor, Louis XII reiterated the French claim. In 1501, he occupied Naples and partitioned the kingdom with Ferdinand of Aragon, who abandoned his cousin King Frederick. The deal soon fell through, however, and Aragon and France resumed their war over the kingdom, ultimately resulting in an Aragonese victory leaving Ferdinand in control of the kingdom by 1504.

The Spanish troops occupying Calabria and Apulia, led by Gonzalo Fernandez de Cordova did not respect the new agreement, and expelled all Frenchmen from the area. The peace treaties that continued were never definitive, but they established at least that the title of King of Naples was reserved for Ferdinand's grandson, the future Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. Ferdinand nevertheless continued in possession of the kingdom, being considered as the legitimate heir of his uncle Alfonso I of Naples and also to the former Kingdom of Sicily (Regnum Utriusque Siciliae).

The kingdom continued as a focus of dispute between France and Spain for the next several decades, but French efforts to gain control of it became feebler as the decades went on, and never genuinely endangered Spanish control.

The French finally abandoned their claims to Naples by the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559.

In the Treaty of London (1557), five cities on coast of Tuscany were designated the Stato dei Presidi (State of the Presidi), and part of the Kingdom of Naples.

Spanish Habsburg and Bourbon Kingdom of Naples

After the War of the Spanish Succession in the early 18th century, possession of the kingdom again changed hands. Under the terms of the Treaty of Rastatt in 1714, Naples was given to Charles VI, the Holy Roman Emperor. He also gained control of Sicily in 1720, but Austrian rule did not last long. Both Naples and Sicily were conquered by a Spanish army during the War of the Polish Succession in 1734, and Charles, Duke of Parma, a younger son of King Philip V of Spain was installed as King of Naples and Sicily from 1735. When Charles inherited the Spanish throne from his older half-brother in 1759, he left Naples and Sicily to his younger son, Ferdinand IV. Despite the two Kingdoms being in a personal union under the Habsburg and Bourbon dynasts, they remained constitutionally separate.

Being a member of the House of Bourbon, Ferdinand IV was a natural opponent of the French Revolution and Napoleon. In 1798, he briefly occupied Rome, but was expelled from it by French Revolutionary forces within the year. Soon afterwards Ferdinand fled to Sicily. In January 1799 the French armies installed a Parthenopaean Republic, but this proved short-lived, and a peasant counter-revolution inspired by the clergy allowed Ferdinand to return to his capital. However, in 1801 Ferdinand was compelled to make important concessions to the French by the Treaty of Florence, which reinforced France's position as the dominant power in mainland Italy.

Napoleonic Kingdom of Naples

Ferdinand's decision to ally with the Third Coalition against Napoleon in 1805 proved more damaging. In 1806, following decisive victories over the allied armies at Austerlitz and over the Neapolitans at Campo Tenese, Napoleon installed his brother, Joseph as King of Naples. When Joseph was sent off to Spain two years later, he was replaced by Napoleon's sister Caroline and his brother-in-law Marshal Joachim Murat, as King of the Two Sicilies.

Meanwhile, Ferdinand had fled to Sicily, where he retained his throne, despite successive attempts by Murat to invade the island. The British would defend Sicily for the remainder of the war but despite the Kingdom of Sicily nominally being part of the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Coalitions against Napoleon, Ferdinand and the British were unable to ever challenge French control of the Italian mainland.

After Napoleon's defeat in 1814, Murat reached an agreement with Austria and was allowed to retain the throne of Naples, despite the lobbying efforts of Ferdinand and his supporters. However, with most of the other powers, particularly Britain, hostile towards him and dependent on the uncertain support of Austria, Murat's position became less and less secure. Therefore, when Napoleon returned to France for the Hundred Days in 1815, Murat once again sided with him. Realising the Austrians would soon attempt to remove him, Murat gave the Rimini Proclamation in a hope to save his kingdom by allying himself with Italian nationalists.

The ensuing Neapolitan War between Murat and the Austrians was short, ending with a decisive victory for the Austrian forces at the Battle of Tolentino. Murat was forced to flee, and Ferdinand IV of Sicily was restored to the throne of Naples. Murat would attempt to regain his throne but was quickly captured and executed by firing squad in Pizzo, Calabria. The next year, 1816, finally saw the formal union of the Kingdom of Naples with the Kingdom of Sicily into the new Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

Flags of the Kingdom of Naples

1282-1442

1282-1442

Angevin flag of Naples

The kingdom adopted the flag of the Spanish Empire when the Habsburg Charles V became King of Naples in 1516.

The kingdom adopted the flag of the Spanish Empire when the Habsburg Charles V became King of Naples in 1516..svg.png) 1714-1738

1714-1738

Flag changed after Charles VI became King..svg.png) 1738–1806; 1815–1816

1738–1806; 1815–1816

Flag changed after Charles VII became King of Naples. Flag was reinstated as the flag of Naples after the Napoleonic Wars..svg.png) 1806–1808

1806–1808

Flag of Naples changed after Joseph Bonaparte became king..svg.png) 1808–1811

1808–1811

Flag of Naples changed after Joachim Murat became king..svg.png) 1811–1815

1811–1815

Flag of Naples changed

See also

References

Sources

- Colletta, Pietro (13 October 2009), The History of the Kingdom of Naples: From the Accession of Charles of Bourbon to the Death of Ferdinand I, I. B. Tauris, ISBN 978-1-84511-881-5, retrieved 20 February 2011

- Musto, Ronald G. (2013). Medieval Naples: A Documentary History 400–1400. New York: Italica Press. ISBN 9781599102474. OCLC 810773043.

- Porter, Jeanne Chenault (2000). Baroque Naples: A Documentary History 1600–1800. New York: Italica Press. ISBN 9780934977524. OCLC 43167960.

- Santore, John (2001). Modern Naples: A Documentary History 1799–1999. New York: Italica Press. pp. 1–186. ISBN 9780934977531. OCLC 45087196.

.png)