Korean mixed script

| Korean mixed script 한국어의 국한문혼용 韓國語의 國漢文混用 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Languages | Korean language |

Time period | 1443 to the present |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 |

Kore, 287 |

| Korean mixed script | |

| Hangul | 한자 혼용 / 국한문 혼용 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 漢字混用 / 國漢文混用 |

| Revised Romanization | Hanja honyong / Gukhanmun honyong |

| McCune–Reischauer | Hancha honyong / Kukhanmun honyong |

.jpg) |

| Korean writing systems |

|---|

| Hangul |

| Hanja |

| Mixed script |

| Braille |

| Transcription |

|

| Transliteration |

Korean mixed script is a form of writing that uses both Hangul (an alphabetical script) and hanja (logo-syllabic characters).

The script has never been used for languages other than Korean. In North Korea, writing in mixed script was replaced by writing only in Hangul in the middle of the 20th century and has not been used since. In South Korea, the use of mixed script has slowly declined.

The script uses hanja to write Sino-Korean vocabulary, but never to write native Korean vocabulary.

History

From the 15th to the 20th century, the Korean mixed script usually used hanja whenever possible (that is, for all Sino-Korean words), and Hangul to write only grammatical suffixes and native Korean words.

Using Hangul to write Sino-Korean words became common in the 20th century. Up to the 1970s, many books and newspapers were written in mixed Hangul and hanja characters. However, as part of de-Sinicization efforts, then-president Park Chung-hee banned the use of hanja in elementary schools in the 1970s, and restricted their use in middle schools and high schools to special optional classes outside the main Korean language curriculum. Since then, the overwhelming majority of print publications are written in Hangul only. Modern texts – whether or not they contain a significant amount of native Korean vocabulary – rarely use hanja for all, or even most, of the Sino-Korean words in the text. Today, this development has reached the point at which most Korean texts are written in a form that can no longer be called mixed script, as hanja are either not used at all, or used very sparsely to disambiguate or to show the meaning of rare or newly coined words (Hanja disambiguation). Only a few people still write in the mixed script. Furthermore, the way in which hanja are used has changed: perhaps owing to a decline in hanja literacy, it has become common to provide both a term's hanja and Hangul at that term's first occurrence in a text – instead of writing it only in hanja as is done in traditional mixed script.

Hanja still appear in many newspapers' headlines, where they serve to both disambiguate and abbreviate, and to a lesser degree in some newspapers' texts, but not in magazines. They can also sometimes be found in academic literature. Mixed script making use of hanja wherever possible is still used for judicial texts such as the constitution (see example below).

Visual processing

When writing in Korean mixed script, semantic or content words were generally written in hanja, while grammatical or function words were written in Hangul.[1]:74 It is possible that this encoding of different types of information into different types of characters speeds up reading, allowing the reader to pass over function words and visually focus on content words, and this feature of Korean mixed script has been praised by some observers, as in the following comment by Insup Taylor:

"An optimal text for efficient visual and semantic processing may be one that uses mixed scripts to enhance visual distinction of semantically important and unimportant words."[1]:75

This sort of advantage in mixed script is why the Japanese written language uses kanji and its native kana in conjunction to this very day. It also enables pure Chinese readers to get some faint gist of the meaning in a given Korean mixed script text from reading the Hanja alone.

Example

The text below is the preamble to the constitution of the Republic of Korea. The first text is written in Hangul; the second is its mixed script version.

- 전문

- 유구한 역사와 전통에 빛나는 우리 대한 국민은 3·1 운동으로 건립된 대한민국 임시 정부의 법통과 불의에 항거한 4·19 민주 이념을 계승하고, 조국의 민주 개혁과 평화적 통일의 사명에 입각하여 정의·인도와 동포애로써 민족의 단결을 공고히 하고, 모든 사회적 폐습과 불의를 타파하며, 자율과 조화를 바탕으로 자유 민주적 기본 질서를 더욱 확고히 하여 정치·경제·사회·문화의 모든 영역에 있어서 각인의 기회를 균등히 하고, 능력을 최고도로 발휘하게 하며, 자유와 권리에 따르는 책임과 의무를 완수하게 하여, 안으로는 국민 생활의 균등한 향상을 기하고 밖으로는 항구적인 세계 평화와 인류 공영에 이바지함으로써 우리들과 우리들의 자손의 안전과 자유와 행복을 영원히 확보할 것을 다짐하면서 1948년 7월 12일에 제정되고 8차에 걸쳐 개정된 헌법을 이제 국회의 의결을 거쳐 국민 투표에 의하여 개정한다.

- 1987년 10월 29일

- 前文

- 悠久한 歷史와 傳統에 빛나는 우리 大韓國民은 3·1 運動으로 建立된 大韓民國臨時政府의 法統과 不義에 抗拒한 4·19 民主理念을 繼承하고, 祖國의 民主改革과 平和的統一의 使命에 立脚하여 正義·人道와 同胞愛로써 民族의 團結을 鞏固히 하고, 모든 社會的弊習과 不義를 打破하며, 自律과 調和를 바탕으로 自由民主的基本秩序를 더욱 確固히 하여 政治·經濟·社會·文化의 모든 領域에 있어서 各人의 機會를 均等히 하고, 能力을 最高度로 發揮하게 하며, 自由와 權利에 따르는 責任과 義務를 完遂하게 하여, 안으로는 國民生活의 均等한 向上을 基하고 밖으로는 恒久的인 世界平和와 人類共榮에 이바지함으로써 우리들과 우리들의 子孫의 安全과 自由와 幸福을 永遠히 確保할 것을 다짐하면서 1948年 7月 12日에 制定되고 8次에 걸쳐 改正된 憲法을 이제 國會의 議決을 거쳐 國民投票에 依하여 改正한다.

- 1987年 10月 29日

- Examples

A newspaper on 30 June 1933.

A newspaper on 30 June 1933..jpg) A newspaper on 14 August 1945.

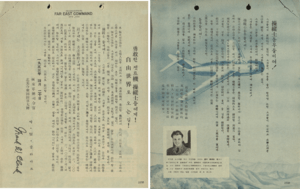

A newspaper on 14 August 1945. Operation Moolah propaganda leaflet by the US Army during the Korean War promising a $100,000 reward to the first North Korean pilot to deliver a Soviet MiG-15 to UN forces.

Operation Moolah propaganda leaflet by the US Army during the Korean War promising a $100,000 reward to the first North Korean pilot to deliver a Soviet MiG-15 to UN forces.

See also

References

Further reading

- Lukoff, Fred (1982). "Introduction." A First Reader in Korean Writing in Mixed Script. Seoul: Yonsei University Press.